4 minute read

The Path Forward

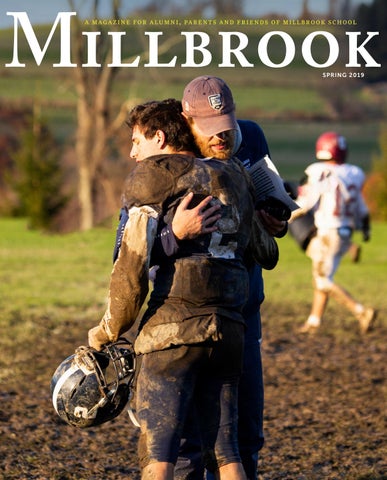

photo by Ricardo Stanoss, DVM

THE PATH FORWARD: community, respect, diversity, service

by Dr. Thomas Lovejoy ’59

SPRING 2019 •

It was the fall of 1955, and I was plucked from a mid-Manhattan existence and dropped into the new third form at Millbrook School. Attracted by the zoo, I had an easy time writing the first assigned essay on why I had chosen Millbrook. Science had no particular hold on me then; indeed, I had announced to my parents that I would take biology the first year and get it over with. Janet Trevor told Frank that either I was really stupid, or I was “casing the joint.” She was correct—happily about the latter.

The Trevors took us on a march through the Plant Kingdom and then the Animal Kingdom, and our classroom went well beyond the four walls of our biology lab, out through the expanse of fields, wetlands, streams, and forests that make up Millbrook’s campus. Before I was 15, I understood the outline of life on Earth. In retrospect, I was so entranced that it is almost unsurprising that one day I would coin the term biological diversity and follow a path to study and protect it.

But that was not all that was going on during this deeply and rapidly formative experience. I was adjusting to a completely new set of classmates from different places and backgrounds, coming to appreciate the countryside, and learning to be part of a community. A new film, Beyond the Classroom, told the story of community service, and there were multiple ways in which we could participate.

While we felt a part of a community with a collective sense of service, inherent in all of this was also an appreciation of difference. We were more privileged than any of us realized, but we were conscious that we were part of something larger and carried that with us as we emerged from our Dutchess County chrysalis. Millbrook had ignited something in us. Ed Pulling expected that we would contribute to the world, each in our own particular way, and he followed our trajectories with delight.

A life of scientific adventures lay ahead for me: to Nubia in 1962 before the new high dam at Aswan flooded a large part of the Nile Valley, and to the Amazon in 1965 when it was only 3% deforested and essentially a biologist’s dream. In my sophomore year at Yale, I had lunch with the world’s most famous birdwatcher, Roger Tory Peterson, at his home in Lyme, Connecticut. I felt like I had died and gone to heaven.

But the early signs of environmental challenges were appearing (Silent Spring was serialized in the New Yorker while I was still at Millbrook), and two years after earning my Ph.D., I became employee number 13 for the World Wildlife Fund-US. I stayed 14 years, instead of the intended two, and applied my science skills, and learned others, to advance conservation. Climate change became hard to ignore, and the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 brought together the largest ever meeting of heads of state.

At that moment humanity witnessed a sense of global community with a common desire to move toward a better future for everyone. Yet, there was less traction than most of us assumed; progress was sluggish because of differing perceptions, of communities that were not sufficiently included, and a global system that failed to deliver necessary resources to advance sustainable development at an appropriate rate and scale. Today, humanity is rapidly pushing beyond the planetary conditions that nurtured the rise of human civilization.

The time to get it together is now or never. Populist, internally-focused governments in some countries are successful in temporarily distracting public attention away from the great planetary challenges of biodiversity loss, climate change, and local issues. It is important to respect and listen, to understand what drives populist votes and how they might be encouraged to embrace the larger sustainability agenda. Happily, public opinion about a sustainable future writ large is actually widespread in those countries. We need to listen to young voices like that of thirteen-year-old Greta Thunberg, who has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize because of her climate activism.

We now understand the Earth works as a linked planetary physical and biological system. Respecting diversity biologically through the restoration of destroyed and degraded ecosystems is a powerful way to increase local sustainability and extract heat-trapping carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. To work at scale, it must work locally.

The way forward—locally, nationally, and globally—rests on the very values that every student learns at Millbrook: a sense of community, which simultaneously respects and engages with the diversity of people and viewpoints, and service that scales from local to global.

Non Sibi Sed Cunctis.