6 minute read

MULTIMEDIA

from 2021-05-20

The Show Must Go On

DOMINICK SOKOTOFF Daily Staff Photographer

The Michigan Theater and State Theatre, located in downtown Ann Arbor, have been home to countless movie screenings and performing arts events for the Ann Arbor and U-M communities in their respective 93 and 79 years of operation. The pair of historic theaters, operated by the Michigan Theater Foundation, have faced a year rife with challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In early March 2020, as COVID19 began to take hold in the state, the Michigan and State theaters closed their doors as per an executive order signed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. The closure was intended to last for two weeks, but as the pandemic worsened, the theaters stayed closed indefinitely, with the marquees displaying reassuring messages such as “Flatten the Curve, See You Soon,” “Good Health to All,” and “Thank You Frontline Heros.”

Through the pause, the theaters offered virtual screenings, custom marquee messages, and concessions to-go. Nevertheless, the theaters averaged a weekly loss of $10,000, and as of September, the theaters had suffered a total loss of more than $1.3 million.

One of the theaters’ primary sources of support during the pandemic came from local community members, who rallied together to contribute via memberships, donations and sponsorships. Although the theaters were able to reopen in October 2020, they quickly had to close back down due to a statewide order in November.

In late January 2021, the theaters were able to reopen for limited in-person screenings. The Michigan Theater symbolically reopened with the film “A Hero for a Night,” which played at the original opening of the theater in 1928.

I visited the theaters in April during a sparsely attended matinee screening. As masked patrons entered, they were faced with temperature checks, hand sanitizer, distancing markers, and plexiglass barriers.

Inside the theaters, there was room for distancing, as the ticketing system guarantees at least six feet of space for each patron and attendance is capped at 50 percent. The concession stands were notably empty and the water and soda fountains closed, in part because masks are required in the theaters.

When the film started, employees wiped down surfaces in the lobby, and tended to tasks, such as changing poster displays and the text on the marquee.

Although the movie-going experience was significantly different, patrons said they were excited to get back out into the community and begin a return to normalcy.

In a January interview with MLive, Russ Collins, CEO and executive director of the Michigan Theater Foundation, remained optimistic about the theaters’ futures, while acknowledging it may take time for some to be comfortable attending in-person screenings.

“The reason that television and subsequently streaming and DVDs and all of those kind of things didn’t put an end to going out (to) the movies is not because you can watch something at home,” Collins said. “It’s about going out. There definitely is a future.”

11

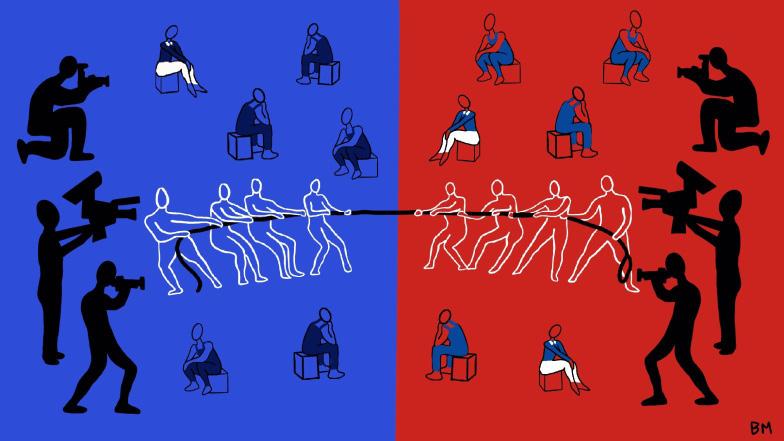

What Macomb County can teach us about American politics

BY IULIA DOBRIN, STATEMENT CORRESPONDENT

Design by Brianna Manzor

Back when blue and red were just Crayola colors to me, I remember sitting around the reading carpet at my elementary school in Macomb County, Michigan, as everyone went around and talked about what their parents did for a living. Almost everyone seemed to have at least one parent who worked for a car company. With my dad working at Chrysler for nearly three decades, I was proud to be a part of something.

Although I moved away from Macomb County years ago, I lived at the Oakland-Macomb border and had strong ties with friends and family in my former area that gave me reasons to be there frequently. Up until high school, Macomb was not much more than a place I called home — full of memories in places that I knew almost innately, like recognizing my own reflection in the mirror. But as I grew past elementary and middle school, I started to follow political trends. Around the same time, I started talking to my dad more about his time working at Chrysler.

I stayed up late last year following the 2020 elections, hearing national news networks talk about Macomb as a representation of the country’s blue-collar workers in the 2016 election — typical blue voters who turned red for the last election. I heard phrases like “growing disgruntled” and “feeling neglected” by both parties.

Having grown up in Macomb, I was surprised to hear this. I felt that I had grown up in a relatively diverse area, at least from all perspectives that I was aware of as a second-grader. Although I knew my dad had his stresses about work, it didn’t seem to be any more than any other work stresses I had seen in TV shows and movies. Nor did my neighbors seem as if they were disgruntled; but then again, 8-yearold me wasn’t talking about politics with my playmates’ parents. I was curious how far the generalized disillusionment spread.

But this sentiment dates back to before 2020, even before 2016. Stanley Greenberg’s 1995 book “Middle Class Dreams” called Macomb “the site of real drama in our political life” because of its battleground status. Between what the media was telling me and what I knew from my family’s personal experiences, I wanted to dig deeper and see what was really happening in Macomb.

Has the media exaggerated the claims of political shifts in Macomb County, or has the dominant ideology really shifted significantly over the years? Has the area become a political microcosm of working-class America?

* * *

My mom recently sent me an article: “White angst keeps Trumpism alive in Macomb County”. This echoed the sentiments of the national media headlines I had seen before, but I wondered how recently this “angst” started. The way I had perceived Macomb County from general media, I was expecting a large shift for the Republicans in 2016 and 2020 compared to a history of Democratic voting before that.

When I looked at election results, I was surprised to find smaller margins than I expected.

Trump had won with 53.6% of the Macomb vote in 2016, whereas Clinton had 42.1% of the vote. However, there were still more Democratic straight-party voters — voters who chose all candidates of one party on their ballot — than Republican that year. The gap slightly closed in 2020, with 53.4% of the vote going to Trump and 45.3% going to Biden, but more Republicans than Democrats voted straight party this time.

I also looked back at voting data and was surprised to see Republican nominee Bush holding the majority as recent as 2004, with his father holding it in 1992. From media portrayal, I had expected Macomb to elect the Democrat candidate every time except Reagan and Trump. With this in the back of my mind, and knowing the importance of the auto industry to Macomb’s economy, I set out to talk to Macomb auto workers about what politics look like on the plant floor.

* * *

Kevin McWilliams is a team leader at the Chrysler plant in Macomb, where he has worked since 2010. Prior to that, he had worked at Chrysler plants outside of Michigan since 1995.

As a member of the United Auto Workers (UAW) — one of the largest unions in North America, representing workers in a variety of economic sectors — McWilliams felt his and his coworkers’ voting was occasionally influenced by who the UAW endorses.