28 minute read

ARTS

from 2020-11-18

The K-pop queens of vocals stage a forgettable return

summer-bop with the cliché The next song makes up for it, JASON ZHANG high-pass filter. It’s nothing though. “Dingga” is everything For The Daily revolutionary. Moonbyul’s “Dynamite” by BTS wished melodic rap perfectly weaves it was. The bouncy bassline The goddesses of vocals, in and out of the otherwise is infectious and invites the Mamamoo, return for their very ordinary and basic song. listener to groove with the crown with their new mini- The song has the classic song. Strings join in for the album, Travel. Their recent Mamamoo slowed-down beat chorus which has a really full track of success with “HIP” rap verse in the middle of the and rich sound, and it’s really and Hwasa’s “Maria” groovy. It combines bass created incredibly drum hits on every beat high expectations with syncopated disco for this album. Aptly elements that create a titled, the project takes inspiration from While their vocals compelling rhythmic drive. Hwasa’s and a plethora of music from around the are perfect, as always, Wheein’s voices lend well to this song, as Hwasa world, ranging from there is an overall brings her sexy sultry the ’70s aesthetic in the U.S. to traditional sense of complacency style, and Wheein really comes into her own as Middle Eastern music. They were quite and mediocrity across a distinct voice in the group. adventurous with their internationally the album — two The title track, “Aya,” seems to rely more on the inspired stylistic things that do not word “Aya” than an actual choices; some of them were used to a great represent Mamamoo melody to be catchy. The flute motif of “Aya” synergistic effect, although other times well at all. pervades throughout the song and carries it the results sounded melodically (I definitely tacky. While their can see it becoming vocals are perfect, as the subject of many always, there is an TikToks and memes). overall sense of complacency song, then ramps back up to the The build-up of the pre-chorus and mediocrity across the chorus. Even the bridge is very to the chorus generates great album — two things that do formulaic, the instrumentation expectations, but the anti-drop not represent Mamamoo well is more sparse and the of the chorus is anticlimactic at all. vocalists trade lines. Overall, and disappointing. The third The mini-album begins with “Travel” is as forgettable as it and fourth verses are the “Travel,” a laid-back, chill is unoriginal. silver lining of the song. The introduction of the low brass in the beat gives it a sort of Latin pop flavor — it’s definitely a killer combination. The faster tempo dance break seems tacked on, like a last-ditch effort to generate some sort of variety within the song, and the ending is sudden and dissatisfying.

“Chuck,” “Diamond” and “Goodnight” carry the album. “Chuck” is a unique sound for K-pop: It starts with a breathy, raspy, quieter singing style complemented by a stripped back synth beat. The chorus features heavier instrumentals, but it’s incredibly catchy. It is such a dramatic and effective sound when the group harmonizes and slides up to a chord, and it really

showcases how wonderful they are as vocalists. “Chuck” also highlights a sexier side of Solar’s voice that we really only got a glimpse of in her single “Spit it Out.”

“Diamond” is badass. The beat is slow but confident. The lyrics are slurred and seem to form one long string of beautiful melody. There are some really funky harmonies in there too — the pre-chorus to the chorus shifting from the G major to A major 7 gives a dreamy, ethereal quality to the music.

The queens of the emotional ballad strike again with “Good Night,” and do not disappoint. In an oversaturated field, filled with incredibly talented K-R&B artists, Mamamoo

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

still manages to stick out. Mamamoo fills the song with their angelic voices, and heaven may actually sound like this.

Travel fails where it needs to succeed; its most important songs, the first and the title track, are lackluster and leave a lot to be desired. The other songs on the album are fantastic but don’t quite make up for it. Mamamoo has consistently been putting out music throughout quarantine, and frankly some of the songs on this album sound like they are burnt out. Maybe they should take a well-deserved break.

Daily Arts Writer Jason Zhang can be reached at zhangjt@umich.edu.

‘The Shadow King’ on our memory of war, violence

her parents, she has seen little If enduring is only one way

ELIZABETH YOON of the world beyond the estate through violence, how can we Daily Arts Writer she works on. Over the course ensure that the violence doesn’t of the novel, her naivete hardens pillage our bodies and person?

The author of one of and she evolves into a soldier. Is there a way to escape war the Guardian’s “10 Best However, Hirut is an abnormal physically and mentally intact? Contemporary African books” protagonist. Mengiste is not Are there metaphysical human has made a triumphant pracious with Hirut. Often, her conditions that get torn out of contribution to the literary world narrative leaves Hirut behind to ourselves during wartime? with her pre-WWII epic “The explore other, more interesting As a contrast to Hirut, Shadow King.” characters. In one scene, Hirut Mengiste also follows Ettore, a

Shortlisted for the Booker is pointedly ignored by two Jewish Italian war photographer Prize for Fiction, Maaza Mengiste embracing characters. While whose psyche and psychology remakes and rebirths Homeric another author might delve into is very clearly laid out. He is mythology in 1930s Ethiopia, Hirut’s feelings of rejection an invader on the other side embarking on an evaluation and confusion, Mengiste does of the war, commissioned to of war, trauma and memory. not indulge Hirut. Hirut is not photograph the triumphant Covering a lightly fictionalized clever or particularly pretty. She Italians. But within the war and Second Italo-Ethiopian War, is not the center of the story. By the Italian front, he is unsafe. Mengiste documents Mussolini’s excluding Hirut’s feelings from Anti-Jewish sentiment seeps invasion of Ethiopia and the the narrative, Mengiste signals from Italy into Ethiopia and people’s resistance. that Hirut herself is tertiary Ettore is anxious and morally

Usually war novels attempt to the larger tapestry of war, conflicted about the atrocities to hold your heart and emotions plunder and Ethiopia being commited against the Ethopians. hostage, harming you with an woven. However, paralyzed by fear that onslaught of devastating events. Menguste’s disregard for Italy’s violence will be turned However, Mengiste’s against him, Ettore tries novel is a beautiful to keep his head down and relatively non- as he documents the traumatic read. Pulling war. At his best, Ettore from both history and Is there a way to is uncomfortable. At his Greek tragedy, Mengiste transforms her forgotten escape war physically worst he is complicit. Whereas Hirut and conflict into a new Iliad, complete with capricious and mentally her cohort become immortalized, Ettore higher powers, intact? Are there remains desperately irresponsible kings and fighting women. metaphysical human small and human, a witness to others’ By including mythic elements (repeated conditions that get greatness. If Hirut and the Ethiopians represent Greek chorus chapters, allusions, etc.), Mengiste torn out of ourselves the subjects of the mythology, Ettore is the helps muffle the dark during wartime? scribe. Continuously topics native to wartime: taking photos and war, rape, assault, documenting the war, extreme violence. Ettore keeps the themes

On one side, fascist of legacy and legend Italy is ramping up their late Hirut is brilliant. It’s one of the alive. imperialism. With better most daring literary choices His photography facilitates weaponry and technology, the made by an author in a long time. the Second Italo-Ethiopian War’s Italians hope for an easy victory. Goodreads reviews reacted to transformation into a legend, However, Ethiopia is not an Mengiste’s tactical disregard by using his camera and viewfinder easy prize to be won, plundered taking umbrage, misinterpreting to create main characters and and stolen. Out of necessity Mengiste’s distance from Hirut sell a narrative to Europe and and national pride, Ethiopian as negligence. Usually, main Ethiopia, producing propaganda generals and households rally characters are celebrated or and stories to sate curiosities. for war, echoing the Greek special in some way. Mengiste Mengiste, through a variety Basileus (kings) who kept their does not coddle Hirut or indulge of angles, transmutes her novel oath to retrieve Helen of Troy in her thoughts and hopes. Instead, and national history into a myth. Homer’s “The Iliad.” Mengiste deposits the same Whereas most myth retellings

The epic begins with the opaque, archetypal figures from try to turn the myths into a main character Hirut fingering myth into her story. Just as you novel, Mengiste does the reverse. through a box of photos taken do not know Achilles or the She immortalizes the fighting by an Italian war photographer. Euripides’ constant thoughts, females of Ethiopia in the form of Through the pictures, Hirut you are similarly shut out from lyrical prose. She constantly and and Mengiste recall trauma and Hirut’s perspective. Like Homer cleverly embeds allusions and violence. And it is through Hirut and Aeschylus, Mengiste makes includes a Greek chorus in her that Mengiste interrogates how you privy to Hirut’s primal rage novel, planting a consciousness one can physically survive battle and confusion but keeps her of legacy and legend. Startling, and emotionally cope with its psychology a secret. She does mythic and vivid, Mengiste’s trauma. Hirut begins untouched this to cleave Hirut and the novel wakes up your senses and unmarred before the Ethipidans closer to legend. She without harming you. beginning of the war. She lives forces the audience to observe Daily Arts Writer Elizabeth a small existence on the edge of and question the impact of Yoon can be reached at elizyoon@ an Ethiopian estate. Having lost violence and wartime. umich.edu.

PIXY Finding warmth in Charlie Brown holiday specials

endearing, and I think part of Guaraldi’s music. Guaraldi

JUDITH LAWRENCE Charlie Brown’s everlasting initially composed for Charles For The Daily charm. There’s a reason Charlie M. Schulz for a documentary Brown has remained a favorite about the Peanuts comics

To say that this past week was for so many after all this time. called “A Boy Named Charlie stressful is an understatement. It’s rather obvious what makes Brown,” and since then he has I found it difficult to focus these specials so delightful, but become integral to the Charlie on anything, whether it was since I hadn’t watched either of Brown legacy. After watching homework or watching a lecture them in so long, I was surprised the specials, I found myself for more than 30 minutes. But at how much I still liked them. putting the soundtracks on recently I’ve rediscovered The animation and color palette while I studied because they’re something very special: the are beautiful and feel like so peaceful. Charlie Brown holiday I also appreciate how specials. I know these short these specials are important parts of are. At 30 minutes each, the holidays, but for watching one of them is whatever reason I had not a big commitment. completely forgotten Finding time to watch about them — until now. It is wonderful that Full of nostalgia and anything is difficult, and especially at times there are three specials joy, these Charlie when focus is hard to for three notable holidays of the fall and Brown specials are a come by. During election week in particular, winter (Halloween, Thanksgiving and sure-fire way to lift anytime I tried to sit down and relax I was Christmas), especially because they’re anyone’s spirits, and instantly distracted by my phone to check perfectly spaced out. who doesn’t want the polls. “A Charlie In October I watched “It’s the Great Pumpkin, that? Brown Thanksgiving” is only 30 minutes, and Charlie Brown,” and it goes by so quickly! this weekend I watched As soon as December “A Charlie Brown comes, I’m going to Thanksgiving.” I watch “A Charlie Brown thoroughly enjoyed both Christmas,” and I highly and was smiling the suggest that you do too. whole time through. they’re right out of the comics. We’re all unsure what these

I’m used to watching That silly spirit is captured so coming months will look like. Disney-Pixar movies where well through the icons that This semester has been so the animation is crazy detailed are Charlie Brown, Lucy, Sally, different from what it should and creepily realistic. Charlie Snoopy and more. They exist have been, and I know I’ve been Brown is the opposite of this, in a world where their parents’ trying to find ways to make but to me, it’s still incredibly voices are replaced by a muted things feel normal. Full of immersive. Movies like trombone. These specials are nostalgia and joy, these Charlie “Monsters Inc.” and “Toy Story” solely from the perspective of Brown specials are a sure-fire are gorgeous and comforting children. This adds to their way to lift anyone’s spirits, and in their own right, but Charlie dreamlike quality, making who doesn’t want that? Brown feels particularly them truly feel like an escape. Daily Arts Contributor Judith nostalgic. Its simplistic One thing that absolutely Lawrence can be reached at animation is whimsical and defines these specials is Vince judelaw@umich.edu.

The Michigan Daily — michigandaily.com14 — Wednesday, November 18, 2020 statement When thousands share one emotion BY ANNIE KLUSENDORF, STATEMENT CORRESPONDENT

Last Saturday I stood in Chicago, across the river from Trump International Hotel & Tower, surrounded by a crowd of strangers. I’d found out the election results half an hour earlier, by way of a CNN push notification, on the 23rd floor of my dad’s apartment building. Within minutes, the honking and cheering pouring through the 12-inch glass window was too loud to ignore. I saw the camaraderie as an undeniable invitation to the celebration, ditched the homework I’d begun only minutes before, grabbed my camera and jumped in the elevator.

I arrived onto the scene at Wacker Drive, a little out of breath after sprinting down Michigan Avenue. Small clusters of people milled around, eyeing each other excitedly. A woman walked past in front of me; noticing we had the same mask and smile hidden behind it, I raised my camera to take her photo. She paused mid-stride and looked directly at me, framed almost perfectly by the raised Wabash bridge beyond her. The irony was too good. (The Wabash Bridge, the only way to the base of Trump Tower, has been raised on and off for weeks “as part of a precautionary measure to ensure the safety of residents.” The street remains closed down a block beyond the tower, enforced by a multitude of maskless Chicago police officers.)

The woman passed through the frame, then, seeing the excitement in my eyes and body language, turned around to chat.

She wasn’t alone in that sentiment. I stayed, watched and photographed for two hours on Wacker as more people streamed in, taking note of the growing festivities: Cars pulled over to take videos, three different people popped bottles of champagne, someone played “The Wicked Witch is Dead” over their speaker, the crowd sang “We Are the Champions” not once but twice, a drummer set up shop, a city worker dedicated his shift to driving his street cleaner back and forth, honking relentlessly.

Oh, the joy. It radiated from everyone in the crowd, almost none of whom knew each other. Eventually, the police blocked both sides of the street to traffic, triggering an impromptu block party. It seemed as if in that moment, like the woman I briefly spoke to, everyone wanted to be with people. But why? ***

In times of high emotion, whether positive — like joy, excitement or relief — or negative — like loss, pain or grief — humans have always come together. We hold protests, vigils, riots, rallies, and celebrations, among many other gatherings.

LSA senior Amytess Girgis, a student organizer who works with the Lecturers’ Employee Organization and a variety of student organizations fighting for equity and justice, has helped organize many different functions for these purposes.

“Our primary focus, when organizing gatherings is to create pockets of liberation, where people can envision the world as it should be,” she said. “And so what that looks like is creating accessible spaces. Spaces where folks with any kind of need can have a presence and not feel like some kind of burden or unwelcome. We create spaces of joy … and then, of course, it’s bringing speakers in that can inspire folks and tell stories. But ultimately, the types of community gatherings I want to be a part of are the ones that tell the story of who we want to be and help people believe that that’s possible.”

The emotions I felt on Wacker Drive were exactly that: I was seeing, and participating in, a future that I hadn’t thought was possible four years ago. First and foremost, it was a collective sigh of relief that our democracy wouldn’t be toppled. Then, at least for me, it was a reinforcement that love, acceptance, inclusion, diversity, morality and empathy were still alive and persevering in our country.

This wasn’t an organized protest, or even an organized gathering. It was a completely spontaneous gathering of people of every ethnicity, sexuality, gender identity and age. We’d previously only felt that joy in microcosmic spaces we’d deliberately constructed. Suddenly, those spaces bled together in the Chicago streets as a celebration of shared freedoms.

Yet as endearing of a sentiment that is, our nation is as divided as we’ve ever been. There was an entire demographic of the country not celebrating in America’s streets last Saturday — one that instead had their moment in November 2016. The concept of celebrating shared principles and values isn’t limited to one side, but right now, it seems to be one side at a time.

The Black Lives Matter movement, founded by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi in July 2013, has long used protesting in the streets to form coherence around the treatment of Black people in America. This past year, America exploded into anger after the killings of George Floyd in May and Breonna Taylor in March, with 74% of Americans saying they support the protests and 15 to 26 million people participating in them.

But the movement quickly fell prey to the “Black is thug” narrative, which evolved into “Black protest is riot.” By definition, rioting is a form of gathering. Sometimes it’s a crowd out of control. Sometimes it’s a deliberate tactic of deterrence, like at the University of Mississippi in 1962, when a white crowd rioted to block James Meredith, the first Black student at Ole Miss, from attending classes. Rioting’s historical significance and current narrative have been marred by those who deem it an illegitimate form of expression.

“The reason why the Black Lives Matter protests were immediately billed as riots is because of how we define violence in a country like America, and in many other places that lean heavily on capitalist ideologies and racist ideologies,” Girgis explained. “And by that I mean that violence on property is the equivalent to violence on real bodies. Vio-

PHOTO BY ANNIE KLUSENDORF

lence on the stock market is the equivalence of violence on real bodies.”

It’s true that small riots have spurned from protests this past year. But it’s also true that historically, rioting has been perpetrated by people of all races, not just Black communities, and as a movement, Black Lives Matter has largely decided to fight inequity and injustice with love and community.

“By combating and countering acts of violence, creating space for Black imagination and innovation, and centering Black joy, we are winning immediate improvements in our lives,” their mission statement reads.

Its principles are clear, and its materials readily available for people to utilize in organizing a community event, rendering the movement impossible to pin down. It can’t be eradicated — it’s not just an organization, but a community of people who believe in a better future, organizing tangible spaces where that belief rings true.

Joy has been part of Black resistance for a long time. “We can actively trace the spatial and temporal control of Black expression from slavery and colonialism through to today,” wrote Chanté Joseph in Vogue this past summer. “This is why the act of joy is resistance and as we use our physical bodies to protest, march and demand change, we must also use them to experience the pleasure of joy.”

For BIPOC in America, and around the world, just existing is an act of resistance. Girgis pointed out how central oral traditions are to these communities — music, dance and art are embedded in their protest. “‘We Shall Overcome’ is one of the most famous movement songs of all time that sort of carries the waves of the civil rights movement,” she said.

On Saturday, the music leaned a little more toward “FDT” by YG and Nipsey Hussle — cars drove past with the song blaring, drenching the crowd in an energy and freedom they’d been missing. That energy couldn’t be contained. And perhaps “FDT” is less traditional than “We Shall Overcome,” but the sentiment still remains the same: A community’s art and culture is woven into the way it decides to gather together.

In the Candlelight Revolution of 2016 and 2017, millions of South Koreans took to the streets every Saturday for 20 straight weeks, demanding President Park Geun-hye’s resignation and the upholding of democracy. The protests were entirely peaceful, focusing around art and entertainment. Youngju Ryu, associate professor of Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Michigan, teaches a class titled “The Candlelight Revolution: Democracy and Protest in South Korea,” and spoke to me about the impact of the incredibly successful demonstrations.

“Throughout the day, this space became the destination for anyone who wanted to express themselves,” she said. “You had a lot of homespun posters, a lot of performances, like puppet shows, you had incredibly satirical examples of what we would call ‘laughtivism.’ So people could go and just walk around and enjoy all these examples of creative and politically engaged voices, and then collectively come together in the evening, listen to speeches by prominent figures and sing together.”

She continued to speak about a sort of collective effervescence found in these scenes.

“The spectacularity of a million people, holding up those candles together ... is something that became an essential part of showing, first of all, how many people there are, and how beautiful it is … I think what helped the protests is, again, kind of understanding the nature of a large crowd like that, and making sure that they remain entertained.”

Almost a third of South Korea’s population turned out in the cold winter, week after week — so much so that Ryu noted a sense of loss after the impeachment was victorious. After 20 weeks of turning out together in pursuit of a common goal, they suddenly found themselves with free Saturdays.

“What’s bringing people together?” Ryu asked. “A strong sense of mission for protecting democracy that was hard fought and hard won ... faith in the power of the masses to bring about such a change, because they’ve done it before.” She continued, “They have this kind of relationship to democracy that I think is more visceral because they experienced authoritarianism in their own lifetime. Many of them fought against earlier, authoritarian regimes in their youth. And so the democracy that they have is something that they have to protect — that they won with their own hands.”

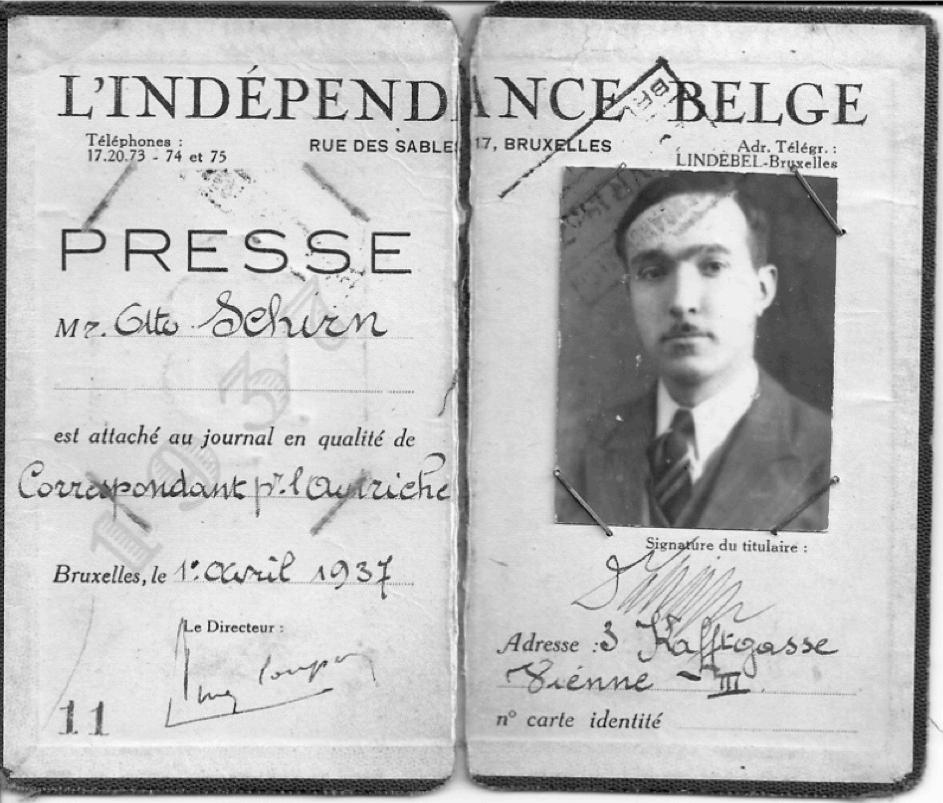

Gazing into my great-grandfather’s shadow

BY SAMMY SUSSMAN, STATEMENT CONTRIBUTOR it will be to rebuild.Editor’s Note: The follow-

But the more I compare ing article is an excerpt from

these two devil’s bargains, a book the author is current-

the more I am forced to ly writing titled “The Search

acknowledge their differ-for Marcel.”

On January 15, ences. In Otto’s case, he 2020 — a day was a fake Belgian journalthat history will ist, an Austrian Jew writremember for the grim pro- ing under a pen name. It cession delivering two arti- was Hitler’s Nazism, not cles of impeachment to the Schuschnigg’s nationalSenate of the United States ism, that forced Otto to be— I first read an article come Marcel. written in 1937 by my great- Unlike our contempograndfather, Otto Schirn, rary leaders, Marcel’s retitled “Chancellor Schus- porting did not normalchnigg’s Work.” ize “very fine people” on

Four months earlier, I both sides of Austria’s had come across a strange existential fight for indocument in my grand- dependence. Marcel acmother’s photo album knowledged Schuschnigg’s about her father’s European authoritarianism for what life. Though I had always it was. He did this while thought of my great-grand- drawing a distinction befather as an Austrian- tween nationalist illiberalJewish refugee — a simple ism and hate-based racism academic who was incred- that would soon turn into ibly lucky to escape in 1941 genocide. with his life — the yellow, Nevertheless, I imagfaded document claimed ine Otto spent the rest of that he was so much more his life questioning his than that. “As a journalist,” support for fascism in the it said. “Dr. Schirn had spo- buildup to the Anschluss. ken against the Nazi gov- After nearly a year spent ernment.” researching Otto’s life, I’ve

I never met Otto; he died come to accept that I will six years before I was born. photo courtesy of sammy sussman question my great-grandHis life had affected me only through the loving memories he left with my grandmother and mother. But as soon as I read those words, I knew I would have to dedicate months of my life to rediscovering Otto’s history. It hinted at a story too powerful to be left untold. From my grandmother’s files, I learned that Otto turned to journalism after four years searching for an academic post. A member of the Vienna University’s inaugural economics doctoral class, Otto would later write to my grandmother of the “casual anti-Semitism” that made a teaching career impossible. Otto spent a year studying journalism in Brussels before he was hired as the Viennese correspondent for “L’Indépendance Belge,” a left-wing Belgian newspaper. He was given the pen name Marcel Legrand to disguise his Jewish identity. From May 1937 to February 1938, he chronicled the fall of Austria’s right-wing fascist party as Austria became part of the Third Reich. In his reporting before “Chancellor Schuschnigg’s Work,” Marcel began to establish two dominating themes that would carry through the rest of his reporting. The first was the hidden motive behind all Austrian political developments: Austria’s fight for independence from an increasingly aggressive German state. Marcel wrote of this struggle as the tragedy it would soon become. The second theme was the increasingly violent strain of anti-Semitism that was taking root both inside and outside Austria’s borders. It was an aggressive institutionalization of the casual anti-Semitism Otto first witnessed in his days at the Vienna University. As he wrote in his second article, Europe would soon face a “Jewish problem” as Britain closed Palestine’s borders to European Jews and Germany sought to instigate the next diaspora. This reporting took place against a backdrop of domestic unrest. Austria’s chancellor, Kurt Schuschnigg, was a noted authoritarian. History would later describe Schuschnigg’s brand of far-right Austrian nationalism as Austrofascism. His predecessor, Engelbert Dollfuss, had seized power by forcing the police to suspend Austria’s legislature. After Dollfuss’s assassination by 10 Austrian Nazis, Schuschnigg’s chancellorship became focused on maintaining Austrian independence, quashing Austrian Nazism and suppressing political dissent. Though in the beginning Marcel supported Kurt Schuschnigg, he did so without acknowledging his anti-democratic tendencies. He wrote of Schuschnigg as the defender of Austrian independence, the defender of Austrian Jews in the face of the violence that lurked on the other side of Austria’s border. But in the article I read on January 15, I watched my great-grandfather’s opinion evolve. For the first time, he admitted his support for an illiberal political figure. “Authoritarianism without dictatorship!” read the article’s subtitle. I wondered if it was written with any sliver of sarcasm. “After the tragic death of Dollfuss,” Marcel began. “Austria found itself at a very dangerous turning point in its postwar history. The whole country was still under the impression of the National Socialist coup d’état.” In two sentences, Marcel summarized Schuschnigg’s powerful response. “Although naturally hostile to the ideas of dictatorship and violence, [Schuschnigg] understood that Austria’s exceptional circumstances warranted an authoritarian government. This is what he achieved without resorting to measures of violence that would be repugnant to the Austrian people.” I was horrified by the contradiction I found in this paragraph, a contradiction that carried through Marcel’s full body of reporting. It was the same contradiction that I see taking place today, the slick realpolitik that sacrifices precedent and principle for the perception of raw political power, the failure to defend the underlying principles of our electoral system in hopes of avoiding the wrath of an outgoing party leader. For my great-grandfather, of course, the stakes could not have been higher. In 1945, he learned that his sister had died of pneumonia. A few months later, he learned his parents had during their transport to Auschwitz. Though he remembered them, Josef and Tauba, they died at 61 and 62, two names among the thousands transported from Malines that day. While writing as Marcel, I believe my great-grandfather thought Schuschnigg was the only person that could prevent the Nazis from destroying his homeland. Marcel was willing to give up his belief in checks and balances, legal rights — the very principles of democracy — in hopes that Schuschnigg might preserve Austria’s independence. He was willing to sacrifice all moral principles in hopes of preventing history’s inevitable outcome: the Anschluss, the fall of Austrofascism and the rise of an Austria Nazi government. As I questioned this moral equivocation, I thought about the life Otto went on to lead in the United States. Why did Otto Schirn, the Austrian-Jewish refugee behind the Los Angeles Holocaust Memorial, once supported an authoritarian chancellor? Why had this academic, who lectured on behalf of civil rights in the early 1950s, support one of the main perpetrators of Austrofascism? Marcel’s position required a cynicism and realism I found chilling. Didn’t he believe that Austria could choose between democracy and Nazism? Couldn’t he see that Nazism would only grow stronger, that it would become more normalized in the sinking democratic power vacuum Schuschnigg’s party had helped create? The comparisons to the politics of contemporary America, Otto’s adopted home, seemed obvious. There was the normalization of racism that accompanied the confirmation of judges, the degradation of ethical norms that accompanied minor tax cuts. Decades of moral principles sacrificed for modest policy advances, a deeply-entrenched political party putting forward a platform of blind fealty. As I look at the choice Otto once made to forfeit morality in pursuit of an end goal, I see a reflection of the choice America’s leaders make every day. I can only hope they do so while knowing how hard father’s decision for the rest of my life. And after watching America’s voters defeat the strongest, most blatant assault on American democracy in recent memory, I realized that many politicians and civil servants must be asking themselves the same question. How did they allow their desire for power or their fear of speaking out to eclipse their allegiance to our Constitution-based democratic system? Over the past week, various political leaders have attempted to cast doubt on the factual underpinnings of this election. Lawyers have worked tirelessly to peel away votes from a specific candidate. Though my great-grandfather’s reporting makes me fearful for the health of our democracy, I take solace in the 5 millionvote margin that separates our government from the fragile ego and destruction of one man. In Marcel’s world, after all, there was no election to save morality. Schuschnigg and his opponents could operate without any fear of a referendum on their policies. Once lost, Austria’s political morality could not be easily rebuilt. As if to prove this point, I noticed a phrase in an article Marcel wrote a month before the Anschluss. The goal of this article was to summarize Schuschnigg’s political legacy; toward the end, Marcel mentioned Schuschnigg’s most recent domestic policies. In all the documents that I’ve read about Marcel’s time, I can think of no better example of the everlasting damage of compromised morality. I fear that America’s current political climate has similarly paved the way for dictatorial destruction in the years to come. Marcel still supported Schuschnigg’s fascism at the time of his penultimate article. He viewed it as a bulwark against the Nazis. But it was of Schuschnigg’s legislation before the Anschluss, not Hitler’s genocide after the Anschluss, that Marcel wrote of a chilling new political development: “the threat to confine all disturbers of social peace to concentration camps.”