4 minute read

Raven, p.98

J ohn W a yn e w a s th e o rig in a l em b o d im en t o f "tru e g rit.' Never mind the intestinal fortitude of the young woman that Wayne, as the leading man in the 1970 screen adaptation of Charles Portis's book, was determined to help. Mattie Rose speaks up, yes. But his voice is absolute gravel; his backbone, ever strong and straight. He is possessed of prodigious guts and steely nerves. Wayne is aptly named "Rooster". He is the idealman of the west.

Allen Ginsberg was no John Wayne. His masculinity was not a cultural given, but rather to be discovered simultaneously with his poetic voice. He first found both by moving west, to San Francisco, in 1954: "Who drove cross-country seventy-two hours to find out if I had a vision / or you had a vision or he had a vision to find our Eternity" [from "Howl"].

I n t h e s a m e y e a r . J a y DeFeo fo unded t h e a r t is t - run S ix G a l l e r y , housed in a form er car repair shop, with husband Wally Hendrick. Ginsberg read the epic "Howl at the Six on October 7,1955. It is said that the San Francisco renaissance emerged that very night with his public performance. Ginsberg's vernacular speech and rhythmic presentation of his accumulations of nouns were akin to the additive method of piling up materials and found objects of the San Francisco assemblage artists who made up much of Ginsberg's audience.

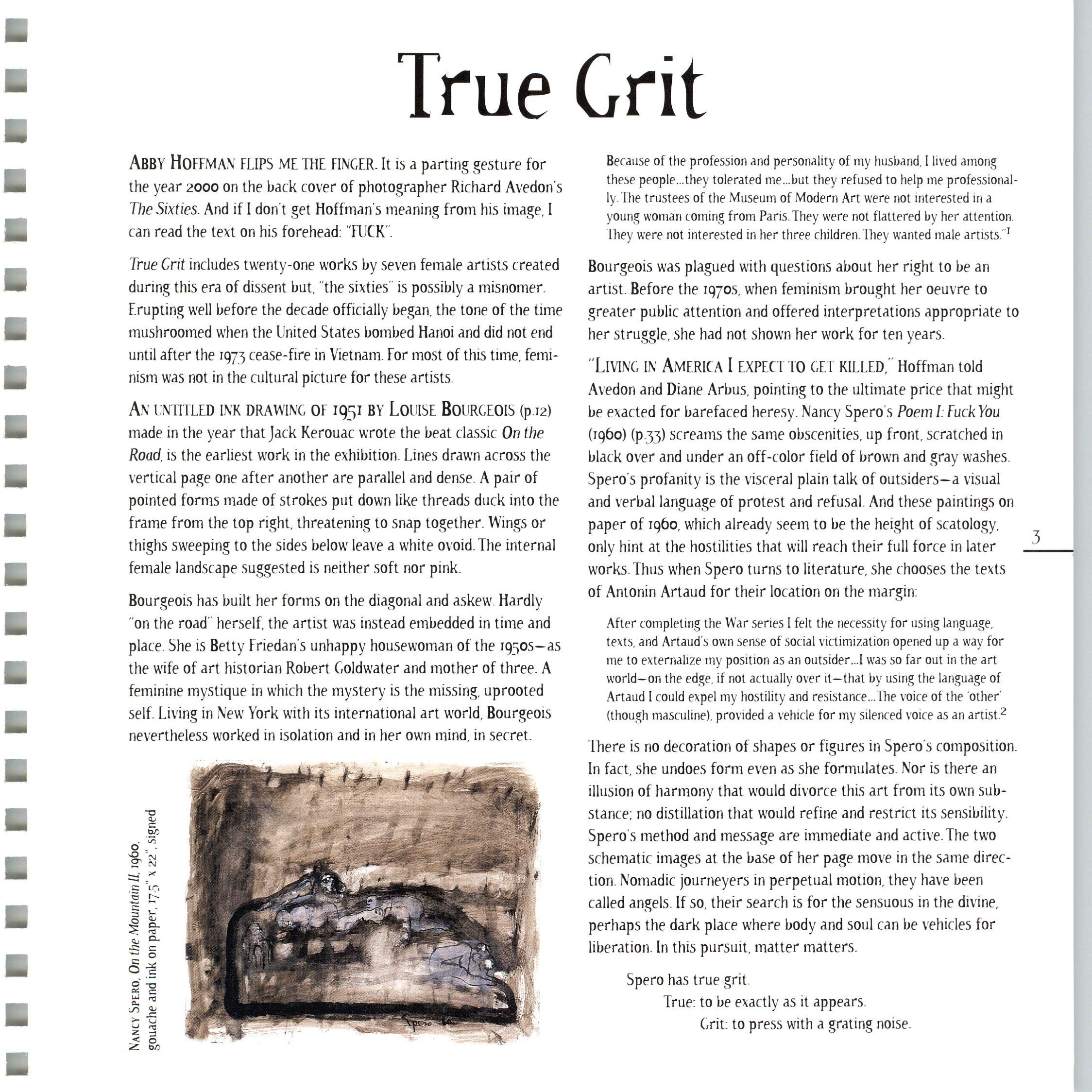

DeFeo would attempt the epic with The Rose. This painting, worked on (and on) between 1958 and 196b, finally weighing in at one ton, utilized plaster to create its single image. Initially, DeFeo's only guideline for The Rose (she told Paul Karlstrom ) was "an idea that had a center to it." The Rose is a cardinal work o f American art exhibited recently at the Whitney Museum of American A rt in The Am erican Century: A rt and Culture 1950-2000. Its contemporary presence provides an opportunity to see DeFeo's art as a part of the past as well as in the context o f the present at once.

The Rose has true grit. Actual size. Originating from the ground. Earth color. With texture. Rooted and embodied.

The senses of smell and sight and sound are often missing from today's virtual dialogues, in which the human being can hide, and a cartoon of perfect proportions take the place o f flesh. The Rose cannot shed its tonnage or its radiance. It is here now.

C l a ir e F a l k e n s t e in ' s s c u l p t u r e m a k e s it s o w n m a t e r ia l s . The artist's initial try at elemental creation coincided with her first attempt at a metal monument of heroic size and scale— the twelve-foot-high steel rod space drawing, The Sign o f Leda. The generation of new substances was highly prized and closely guarded in 1953. The Rosenbergs had, a fter all, been executed for sharing the secrets of matter.

Falkenstein was determined to ca rry through her process as a direct technique. By brazing stove-pipe with iron wire to form volumes, she ceased to sim ply design form and actually began to make her medium. Falkenstein's experiments in topology and molecular structure often pushed the envelope. "I experimented and invented a new technology, fusing glass to the web of welded metal by putting both in a kiln together. Engineers said it couldn't be done, but I found a way to make a molecular bond. Instead of being flat, the molten glass flowed around in different directions, caught in the three-dimensional web of metal."3

Falkenstein wondered at the composition of the cosmos but her earliest memories are of making a universe of her own. She fashioned small animals out of wet d ay at the edge of the bay where her family spent summers. "1 began to amuse m yself by making an environment around the tru n k of a tree. I made a house and gardens, and found little pieces of glass fo r lakes and pools... I remember it as my first creative w ork done freely.

N an cy G r o s s m a n r eflec ts on th e N e w Y o r k a r t c o m m u n it y

in i9 6 0 in this way: "It was simply too much of a challenge for a young woman to announce that she was an artist. Because all artists were feminized, male artist bent over backwards to present their most macho aspect. Grossman and Anita Siegal had to keep the sec ret-th e y were artists who made tough work. Instead, they would pretend that they didn't know anything about art, but were "just two chicks, all gussied up in our best thrift shop finery, faces painted. "4