17 minute read

GOALS OF THE STUDY

Mission + Vision

Our mission was to produce a plan with recommendations to help preserve the physical condition and affordability of naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) in the Oakman Boulevard Community neighborhood of Detroit, in light of the construction of the Joe Louis Greenway. The outcome of our project aims to offer the City of Detroit’s Housing and Revitalization Department (HRD) NOAH preservation actions based on accessible data to support both the Oakman Boulevard Community neighborhood and other similar neighborhoods. We hope that this analysis will equip decision-makers with wellresearched evidence of public action that can support NOAH landlords to maintain affordable rents while improving the physical property condition.

Advertisement

Many American cities are turning to greenways as part of their urban redevelopment strategy, with examples such as Atlanta’s BeltLine and Chicago’s 606 Trail. Those greenway experiences show that they have been successful in attracting development and new residents to urban neighborhoods that have long experienced disinvestment. However, greenways can also raise concerns about potential economic and social costs for disadvantaged populations due to the loss of affordable housing as a result of increased investment in these neighborhoods. A similar greenway initiative, the Joe Louis Greenway (JLG), has begun development in the City of Detroit. Partnering with HRD, our team has examined the availability and characteristics of small-multifamily NOAH properties in the Oakman Boulevard Community neighborhood located in the Northwest section of the greenway, identified the risks those properties are facing, and proposed five pertinent. recommendations to promote the preservation of such housing.

The Joe Louis Greenway

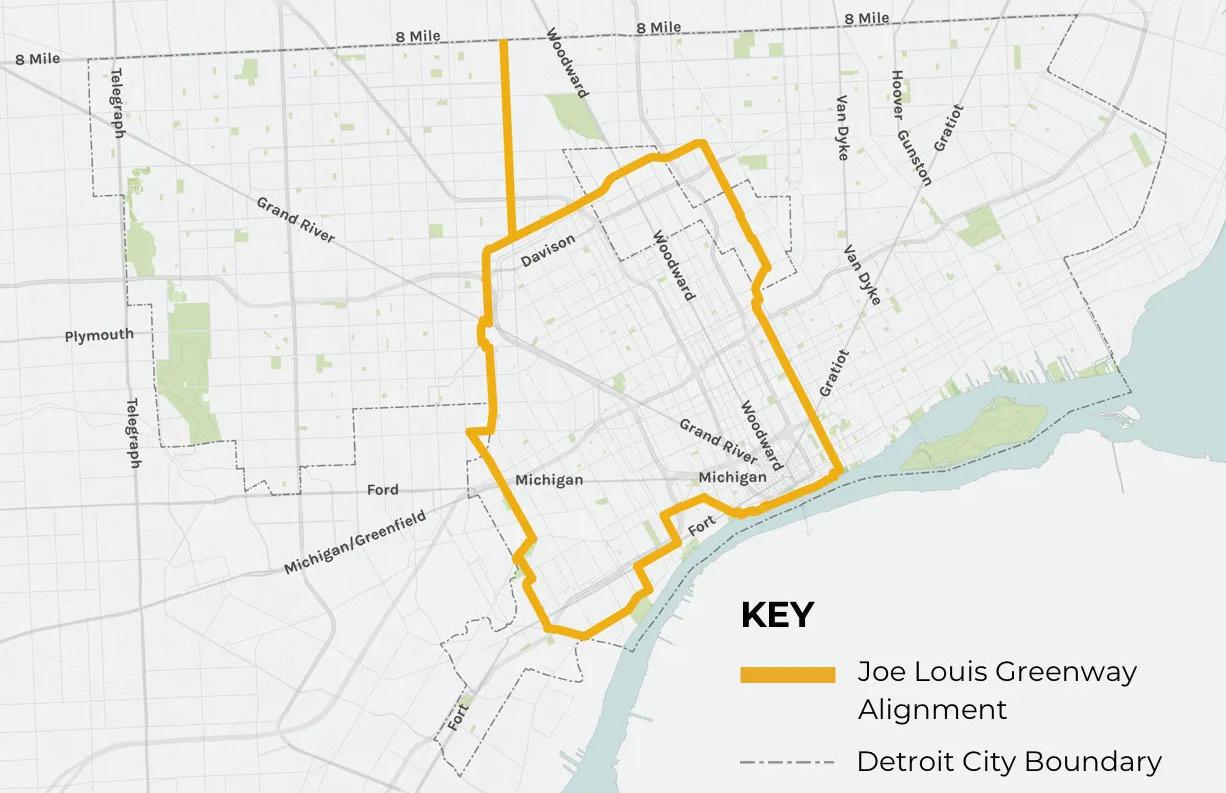

The Joe Louis Greenway is a 27.5-mile walking, hiking, and biking trail project initiated by the City of Detroit in partnership with the cities of Hamtramck, Highland Park, and Dearborn.1 Construction began in 2022 and is part of a broad vision for the City. As shown in Figure 1, the JLG will connect residents and visitors of more than 20 communities, consisting of on- and off-street protected bike lanes and walking paths, connecting to existing paths such as the Dequindre Cut, Detroit Riverwalk, and the Iron Belle intrastate trail. 2 To examine JLG’s potential impacts on nearby neighborhoods, we first looked at research done on similar greenway projects in other cities to identify some key lessons.

Lessons Learned: Implications from Atlanta and Chicago

Atlanta BeltLine

The Atlanta BeltLine is a 22-mile loop of existing and proposed shared-use trails surrounding Atlanta, Georgia. Acting as an impetus for the JLG, the BeltLine uses former railroad right-of-way to connect 45 neighborhoods that were historically divided by race and class. Supported by a public-private partnership and managed by Atlanta BeltLine Inc., the BeltLine aims to build “a more equitable and inclusive Atlanta and engage partners by delivering transformative public infrastructure that enhances mobility, fosters culture, and improves connections to economic opportunity.”3

The first segment of the BeltLine opened in 2008. As other portions of the BeltLine opened, many neighborhoods, especially along the Eastside trail of the BeltLine, have been experiencing gentrification as new developments have increased. Rents and property values have accelerated as investors purchased adjacent properties at low costs and converted them to highend living.4 In 2022, renters paid more than 50% higher to live along the Eastside trail of the BeltLine compared to 2021. In Reynoldstown, a neighborhood along the Eastside trail, rents increased by 54% with a one-bedroom apartment lease starting at $2,000 per month.5

The rapid changes in affordability along the BeltLine have raised concerns of displacement in the majority-Black and low-income neighborhoods in the south and west sides of Atlanta, which have experienced decades of disinvestment. Landlords are likely to increase rent in light of higher property taxes and higher demand for housing along the BeltLine.6 To protect long-time Atlanta homeowners, the BeltLine implemented its Legacy Retention Program. The Legacy Retention Program provides property tax assistance to Atlanta homeowners on the west and south sides of the trail by covering the cost of property tax increases through 2030. However, the program provides no mechanism that protects renters.7

Chicago’s 606 Trail

The 606 Trail (also known as the Bloomingdale Trail) is a 2.7-mile shared-use elevated trail built on an abandoned railway in Chicago’s northwest side. Completed in 2015, the 606 connects four diverse neighborhoods with a potential expansion eastward toward the Lincoln Yards development site. The $95 million project was funded in part by the federal, state, and local government as well as philanthropy, and is managed under a public-private partnership.8

Following the 606’s opening in 2015, gentrification has been rampant in close proximity to the trail. The eastern segment of the trail, home to a majority white and affluent neighborhoods of Bucktown and Wicker Park, has experienced gentrification dating back to the 1980s and the addition of the trail has only marginally increased gentrification in the neighborhoods.9 However, the western segment of the 606, home to the working-class neighborhood of Logan Square and the majority-Hispanic Humboldt Park neighborhood, experienced significant price increases driven by demand and desire to be close to the 606.10

Properties along the 606 are significantly at risk of being converted to luxury housing. Older multi-family apartments with belowmarket rents are being sold and demolished for single-family homes or luxury condos, causing widespread displacement, rising rents, and loss of community character.11 In response, the Chicago City Council passed a temporary moratorium on demolitions close to the 606 in January 2020. Then, in January 2021, the City Council passed a “deconversion ordinance” that bans singlefamily homes without a zoning change on blocks where greater than 50% of the lots are multi-family buildings.12

Lessons for Detroit

The Atlanta BeltLine and Chicago’s 606 Trail provide insights into the potential effects on housing that Detroit’s Joe Louis Greenway may have. In both greenways, following the completion of the trail, rents have increased significantly, and disadvantaged populations have faced greater housing instability.

The effects of the greenways present concerns that the Joe Louis Greenway could also convert existing affordable housing into market-rate housing and increase housing instability for vulnerable populations. In a city that is majority Black and low-income, the impacts of the Joe Louis Greenway would potentially be more striking when compared to Atlanta and Chicago.

In the Oakman Boulevard Community neighborhood, where the Joe Louis Greenway is situated at the northern end of the neighborhood, the economic effects of greenway investment can attract new residents and housing developments to the area. As demand for housing in the neighborhood increases, owners of properties that are currently affordable would have the incentive to increase their rent to maximize revenue. This would place existing tenants at risk of losing the only housing they are able to afford, creating an affordable housing crisis in the neighborhood and disrupting livelihoods.

Atlanta and Chicago offer lessons that are applicable to Detroit. City leaders must be cognizant of the implications on housing that the construction of the Joe Louis Greenway continues to have and ensure the preservation of existing affordable housing properties.

Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH)

NOAH in Detroit

The Detroit housing market is unique. Unlike many major U.S. cities, Detroit is known for an oversupply of housing and a high vacancy rate. A quick drive around most Detroit neighborhoods will reveal numerous vacant housing units, many of which are falling into disrepair. Despite the ample supply of housing, decades of discriminatory housing policies, divestment, and exploitive lending practices have limited the availability of affordable rental housing units that are in safe condition in Detroit.13 In 2021, sixty percent of Detroit households living in rental units were cost burdened, meaning they spent over 30% of their income on housing, and thirty-three percent were severely cost-burdened, meaning they spent 50% of their income on housing.14

This study focuses on preserving NOAH in the Oakman Boulevard Community neighborhood in Detroit. According to the definition used by the City of Detroit, NOAH properties are unsubsidized, privatelyowned housing units that are affordable to households earning 60% or less of the Area Median Income (AMI). Since NOAH properties are privately owned and do not carry public subsidies, they are not subject to government affordability restrictions. As a result, their status as affordable housing can change quickly due to market forces. In areas with growing demand, owners may choose to raise rents. Meanwhile, in areas with weak demand, owners may find it difficult to keep affordable units in decent condition, which can lead to physical deterioration and the eventual loss of units from the affordable housing stock. Furthermore, NOAH properties are not subjected to the same inspection processes as subsidized housing.15 Registered Detroit residential rental properties are required to submit to annual physical inspections and obtain a lead clearance certificate. However, many NOAH properties in Detroit are not registered and are thus not subject to annual physical inspections.16 To complicate matters further, many rental registered properties have not obtained their certificate of compliance limiting the base level inspection and lead clearance necessary to provide a safe renting condition. Furthermore, the high median age of residential properties in Detroit – and specifically the Oakman Boulevard Community17 – dictates that further maintenance and renovation efforts are required for these properties to maintain a livable standard.

NOAH in Oakman Boulevard

Since NOAH properties need to be affordable to households making 60% of AMI, their rents should be less than 30% of this household income level.18 Based on this definition, in 2022, a one-bedroom NOAH unit would be rented for less than $1,000 per month and a two-bedroom NOAH unit would be rented for less than $1,209 per month. One issue is that AMI is defined at the metropolitan level. Given that the City of Detroit has much lower household income than the surrounding suburban communities, most of the unsubsidized housing units in the Oakman Boulevard Community neighborhood fall within the NOAH criteria. Since properties of different sizes may have different dynamics, our project focuses on a particular type of NOAH properties: small multi-family rental properties with between 4 and 36 units.

Throughout this report, we will refer to this specific grouping as NOAH properties. Much of the housing stock within Detroit consists of single-family or single-family conversions to properties under five units, so this study does not capture the majority of NOAH properties that exist in Detroit.

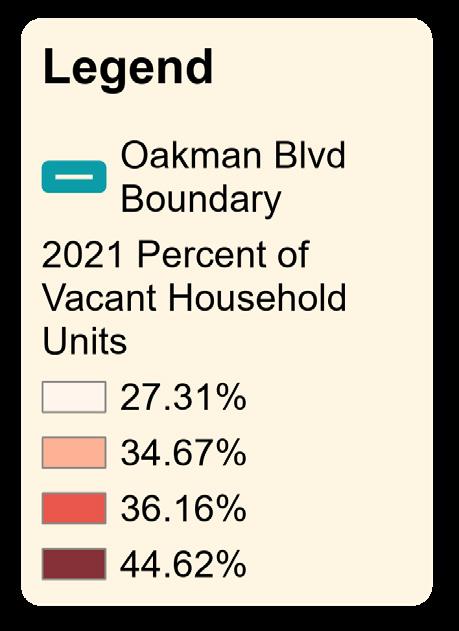

The Oakman Boulevard Community

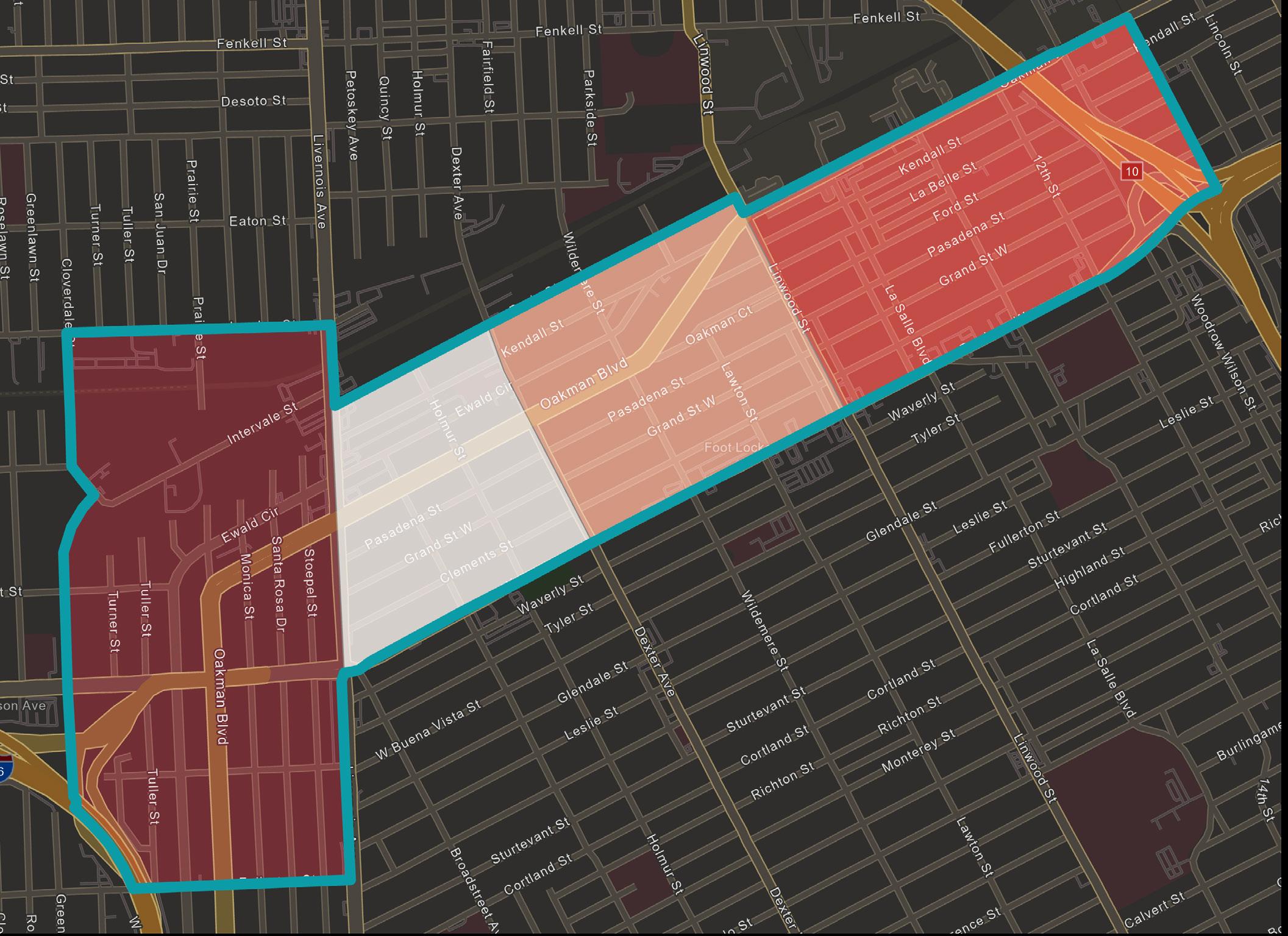

This study focuses on the Oakman Boulevard Community along the JLG. To be consistent with the City’s work on the Greenway, we used the same neighborhood boundary that the Detroit Planning and Development Department has identified in their JLG planning study. Based on this definition, Oakman is a neighborhood that is made up of four census tracts (Tract 5304, Tract 5316, Tract 5317, Tract 5365) as shown in Figure 2. In total, Oakman has 6,228 people, 2,640 households, and 4,104 housing units.19

90.76% of the population identifies as Black or African American (one race), which is much higher than the City-wide percentage of 77.9%. 20 In addition, Oakman appears to be composed of a higher female demographic when compared to the City, particularly in Tracts 5304 and 5316. Meanwhile, the age of the population within Oakman seems to be rather consistent with the City as the voting age population is within 5% of the City’s percentage. One other important takeaway is that Oakman appears to have a higher prevalence of non-family households when compared to the City, especially in Tract 5317. Therefore, when compared to the City, the Oakman community is a majority Black community that is likely to have a higher demographic of single, female-led households.

Another important consideration of the Oakman Boulevard Community would be its housing and economic characteristics. The data in the chart below breaks it down by census tract to gain a deeper understanding of this area. As Table 1 shows, the Oakman Boulevard Community stood out for several characteristics:

• Oakman has a total of 2,640 households and 4,104 housing units.

• The majority of occupied housing is made up of rental housing.

• The census tract with the highest median household income (Tract 5365) is almost 1.5 times greater that of the lowest (Tract 5304).

• The vacancy rate in Oakman is consistently higher than the City.

• The homeownership rate in Oakman is consistently lower than the City.

• The median housing value stays relatively the same across all four census tracts.

• The median gross rent differs rather significantly between tracts (Tracts 5316 & 5317 are around $700 whereas Tracts 5304 & 5365 are around $800).

Note: All data has come from the ACS 2017-2021 estimate except for median household income in Tract 5317, where the data is not available for this estimate. Instead, we used the median household income data from ACS 2016-2020 estimate for this tract.

When observing specific trends within the Oakman Boulevard Community, one key takeaway is the significance of Tract 5317. Tract 5317 has the highest median age (46.8) and the lowest median household income ($20,980). In addition, it has the lowest median gross rent ($714) and the highest unit vacancy rate (44.62%). Of particular interest is this tract’s relation to the NOAH properties we will identify next: it contains 20 of our 45 target properties. This indicates that Tract 5317 is an extremely valuable location for affordable living conditions. Further Oakman Boulevard Community demographic and statistical maps can be found in Appendix A.

Due to its high vacancy, lower rents, and aging population, Tract 5317 is at higher risk for land speculation and rapidly increased land values. Census data has revealed that over 13% of the vacant units sold in this tract have remained unoccupied. This is nearly double the next closest percentage (6.62% in Tract 5306). 21 Therefore, this may indicate that either properties in Tract 5317 are currently being acquired out of speculation and the purchasers are waiting for favorable market conditions, or purchasers are buying property to renovate in conjunction with the near-term development of the Joe Louis Greenway.

Given that the Oakman neighborhood has some compelling characteristics, it is likely to be more greatly impacted by changing market conditions. When compared to the City at large, these characteristics, including lower rents, higher percentages of nonfamily households, lower median housing value, higher median age, are all potential risk factors that correlate with the property analysis findings within this report.

Endnotes

1. Joe Louis Greenway. (n.d.). City of Detroit. https://detroitmi.gov/ departments/general-servicesdepartment/joe-louis-greenway

2. Joe Louis Greenway Framework Plan Vol. 1 The Vision. (2021). General Services Department, SmithGroup, Studio Incognita, Sidewalk Detroit, Toole Design, & HR&A Advisors. Detroit, MI; City of Detroit.

3. About Us. Atlanta Beltline. (n.d.). https:// beltline.org/about-us/

4. Immergluck, D. (2022). Chapter 2: The Beltline as a Public-Private Gentrification Project. In Red hot city: Housing, race, and exclusion in twenty-first century Atlanta (pp. 59–94). essay, University of California Press.

5. Areas around Atlanta See Rent Increases as High as 83% over Last Year. WSBTV Channel 2 - Atlanta. June 3, 2022. https://www.wsbtv.com/news/local/ atlanta/areas-around-atlanta-seerent-increases-high-83-over-last-year/ ATIMRW2BHBGDXII4VNELERDIOY/.

6. Immergluck, D. 2022.

7. Brey, J. (2021, May 4). The Atlanta Beltline Wants to Prevent Displacement of Longtime Residents. Is It Too Late? Next City. https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/ the-atlanta-beltline-wants-to-preventdisplacement-of-longtime-residents.

8. Frequently Asked Questions. The 606. (2019, May 31). https://www.the606.org/ resources/frequently-asked-questions/.

9. Lee, W. & Greene, M. (2019, June 21). Neighbors Have Embraced the 606 Even as Gentrification and Crime Create a Divided Playground. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune. com/news/breaking/ct-606-trailneighborhoods-20190623-20190621ilxlcfqhjffkfgt6rx5k7fyn34-story.html.

10. Smith, G. et al. (2016, November 1). Measuring the Impact of the 606. Institute for Housing Studies - DePaul

University. https://www.housingstudies. org/releases/measuring-impact-606/.

11. Black, C. (2020, January 30). “Green Gentrification” and Lessons of the 606. The Chicago Reporter. https:// www.chicagoreporter.com/greengentrification-and-lessons-of-the-606/.

12. Laurence, J. & Peña, M. (2021, January 28). New Ordinance Makes It Harder to Turn Apartments into Single-Family Homes along 606 and in Pilsen. Block Club Chicago. https://blockclubchicago. org/2021/01/27/new-ordinance-makesit-harder-to-turn-apartments-into-singlefamily-homes-along-606-and-in-pilsen/.

13. Risk Profile: Distressed NOAH Property Affordable Housing Preservation Strategies. (2021). Detroit Preservation Partnership.

14. 2021 ACS updates. (2022). Detroit Future City.

15. Risk Profile: Distressed NOAH Property Affordable Housing Preservation Strategies. (2021). Detroit Preservation Partnership.

16. Rental Dwelling Inspections Requirements. (2018). City of Detroit Property Maintenance Division.

17. U.S. Census Bureau, “Median Year Structure Built, 2021 5-Year Estimates.”

18. Detroit Preservation Action Plan. (2018). Detroit: City of Detroit.

19. U.S. Census Bureau, “Demographic and Housing Estimates, 2021 5-Year Estimates.”

20. U.S. Census Bureau, “Demographic and Housing Estimates, 2021 5-Year Estimates.”

21. U.S. Census Bureau, “Occupancy Status, 2020 DEC Redistricting Data.”

Methodology

General Approach

To identify the scope and process for our project, our team began with a literature review. We conducted an extensive literature review to learn more about the Oakman Boulevard Community, the Joe Louis Greenway’s potential impacts, and NOAH housing in general.

After our initial literature review, we split into three teams for context-specific research. Details of each team’s research methodology is included in the following sections.

• Property research to collect and analyze market data on individual NOAH properties and the Oakman Boulevard Community.

• Neighborhood level research and outreach to understand the challenges and opportunities within Oakman.

• Research of the existing NOAH policies and programs available in Detroit and other relevant U.S. cities.

Property Analysis Methodology

Overview

Using open source data, our research team developed a process to identify small multifamily NOAH properties in the Oakman Boulevard Community. In addition to the Open Data Portal, we also used Data Driven Detroit’s Housing Portal and Multiple Listing Services (MLS) to refine and corroborate our findings. For the purpose of this study, our team defined small multi-family NOAH properties as those containing between 4-36 units. Each of these NOAH properties are analyzed in more detail in property profiles which can be seen in Appendix B. Appendix C provides a detailed explanation of the database methodology.

Generating & Refining Small Multi-family NOAH Property Data

Using the City of Detroit assessor’s data as the foundation for property identification, we first identified all properties within the Oakman Boulevard Community. This property dataset was then refined using queries to isolate properties based on property tax classification, land use type, taxpayer identification, and taxpayer addresses. To corroborate the data identified through queries, site-specific property research was necessary. This process required our team to investigate individual properties and individually filter out those that did not meet specific target identifiers for NOAH properties (Transitional housing; Regulated affordable housing (Section 8); Vacant properties; Properties used solely for commercial purposes). Once the 45 properties were identified, we compiled a small multi-family NOAH property database that includes the most pertinent property information for analysis.

Examining Recent Market Trends

Property sales data available from the City’s Open Data Portal provides useful information about the turnover rate of property ownership in a neighborhood. It also allows us to examine changes in property sales prices that may impact future rents and increase the burden on low- to middle-income tenants. Analysis of sales data is important to understand market trends and potential future risks to NOAH housing.

In order to connect transaction data to the aforementioned 45 NOAH properties, we counted the number of transactions each individual property went through from 2011 to 2022. To ensure that we counted valid market sales, we applied criteria to exclude non-sale transfers or sales where financial institutions or government entities were

Source: Authors’ work” receivers of properties indicating mortgage or tax foreclosures.

Community Engagement Methodology

An integral aspect of this project was engagement with stakeholders and experts to get their perspectives on the issues facing the Oakman Boulevard Community neighborhood and how the Greenway may affect the neighborhood. We either attended meetings or conducted interviews with the following groups.

Meeting: Detroit Planning and Development Department, Joe Louis Greenway (JLG) Team

The Detroit’s Planning and Development Department is conducting ongoing outreach and engagement with the communities that will be impacted by the JLG team. To ensure that we were building off of existing work rather than replicating it, the JLG team shared their outreach and research plan as well as insights and recommendations for our outreach and research efforts.

Interview: HOPE Village Revitalization

HOPE Village Revitalization “is a community controlled organization committed to improving the quality of life in the Hope Village neighborhood.”1 The HOPE Village neighborhood overlaps with the Oakman boundary, although it covers a slightly larger area than our study area. Our team met with HOPE Village representatives to learn insights regarding the challenges and opportunities for tenants and property owners in Oakman.

Interview: Oakman Boulevard Community Association (OBCA)

Our team had a virtual meeting with representatives of the Oakman Boulevard Community Association (OBCA) which is a resident-run neighborhood association that aims to “bring together residents of the Oakman Boulevard Community in order to achieve a better community in which to live, foster interest in civic affairs by providing opportunities for discussion of common neighborhood issues, and to act in concert to resolve these issues.”2 The OBCA neighborhood boundary represents the historic district, which overlaps with the study area. They provided valuable insight regarding the challenges and opportunities for tenants and property owners in Oakman.

Interview: Neighborhood Service Organization (NSO)

Our team members met with the Chief Community Impact Officer at NSO which is located on Oakman Boulevard. NSO is an organization that focuses on holistic care for residents, especially working with folks who are unhoused, older adults with mental illness, and people with developmental disabilities. By interviewing them, we hoped to get a better understanding of the needs of the residents because we did not have the opportunity to directly engage residents due to time constraints.

Meetup: Metro-Detroit MultiFamily Housing Investors, Southfield, MI

Members of our team had informal conversations with multi-family housing investors at a meetup event. At this networking/social event, our team members held informal conversations with roughly ten attendees, some of whom were landlords in Metro Detroit. Those conversations helped us understand the challenges and motivations in operating rental properties in Metro Detroit.

Interviewing Detroit Landlords

One of the most challenging community engagement groups to connect with were landlords. Research on NOAH housing in Oakman offered contact information for eighteen of the forty-five target properties.

Prior to making contact with these property owners and/or managers, we developed a list of interview questions. Depending on the specific property and contact person, the number of questions asked varied.

Phone calls were made to all eighteen properties, and when available, emails were also sent. Unfortunately, as we will discuss in the limitation section, we did not succeed in carrying out interviews with those landlords.

In supplemental Oakman landlord interviews, we did manage to interview two Detroit landlords with properties outside of Oakman. The questions asked in these interviews excluded those questions that are specific to Oakman.

Community Engagement Event: Joe Louis Greenway Planning & Development Department

Members of our team attended a community engagement event hosted by the Detroit Planning and Development Department to gather resident input on the Joe Louis Greenway. The structure of the community engagement event allowed for public participation, including comments and questions. While the focus of the event did not directly align with our project goals, some public input did involve concerns with housing affordability.

Windshield Survey

In addition to meetings with stakeholders and experts, our team conducted a windshield survey to view all 45 target properties. We developed a scoring system to rate the physical condition of the visible property exterior. The scoring scale is indicated below.

1 - Uninhabitable

2 - Major repairs required

3 - Minor/cosmetic repairs required

4 - Good condition

To rate each property, we parked in front of the property and discussed the features, if any, that warrant a loss of “property condition” points. The three team members discussed the significance of the needed repairs to determine the appropriate point value. The score was discussed until a unanimous decision was made.

Policy Research Methodology

Our team sought to understand the current state of policies and strategies for NOAH preservation that have been or could be applied in Detroit. We researched existing policies at the local, state, and federal levels that support or in some way impact NOAH preservation; such policies implemented in comparable cities; and regional nonprofit and philanthropic organizations that have addressed NOAH preservation. This established a baseline for further research, helped to identify regional experts who could be interviewed, and assisted in the development of questions to ask and topics to research.

Our team developed a list of organizations and experts to interview to discuss the success of existing policies and get their perspectives on the viability of potential new strategies. The team was able to schedule and conduct interviews with representatives from Southwest Housing Solutions, Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) Detroit, the Policy Team at Detroit’s Housing and Revitalization Department (HRD), as well as a University of Michigan Poverty Solutions Fellow who had worked with United Community Housing Coalition (UCHC). Each interview was 30 to 45 minutes in length and the interviewee’s experiences with the rental market in Detroit, their thoughts on the success of existing policies, and their personal opinions on the potential benefits of new policies were discussed.

Endnotes

1. HOPE Village Revitalization. (n.d.). hopevillagecdc.org/about-us/#hvrmission

2. Oakman Blvd Community Association. (n.d.). from https://oakmanblvd.org/