9 minute read

cannabis landscape

from Boheme Fall 2020

by Weeklys

Cannabis KALEIDOSCOPE

On pot, the pandemic and price

BY JONAH RASKIN

In the middle of July, growers, dispensary owners, distributors and consumers told me that illicit weed was bringing in more money per pound than legal weed. My sources also told me there was a cannabis drought, though I knew that California had been overproducing weed and shipping it out of state where it fetched higher prices than close to home. » »

“See you at

Chase Bank Red Hill!” CVS Get in Shape for Women Gold Dreams Jewelry & Damselfly Unlimited Boutique High Tech Burrito Hot Wok Chinese Food JOLT! Kitty Corner Lark Shoes LUX Blowdry & Beauty Bar Mathnasium of San Anselmo Peet’s Coffee & Tea

Pet Food Express Pizzalina Precision 6 Haircutting Red Hill Cake & Pastry Red Hill Holiday Cleaners Safeway Sophie’s Nail Spa Subway Sandwiches Swirl Frozen Yogurt The Hub Vine Wine Shop & Bar West America Bank

Take out and delivery available for all restaurants Outdoor set-ups for Nail Salons and Hair Care

Chase Bank CVS Get in Shape for Women Bella Boutique High Tech Burrito Hot Wok Chinese Food Jillie’s Wine Bar and Shop JOLT!

Kitty Corner Red Hill Holiday Cleaners Lark Shoes Safeway Mathnasium of Sophie’s Nail Spa San Anselmo Subway Sandwiches Peet’s Coffee & Tea Swirl Frozen Yogurt Pet Food Express The Hub Pizzalina West America Bank Precision 6 Haircutting Chase Bank Red Hill Cake & Pastry Pet Food Express CVS Pizzalina Get in Shape for Women Precision 6 Haircutting Gold Dreams Jewelry & Red Hill Cake & Pastry Damselfly Unlimited Boutique Red Hill Holiday Cleaners High Tech Burrito Safeway Hot Wok Chinese Food Sophie’s Nail Spa JOLT! Subway Sandwiches Kitty Corner Swirl Frozen Yogurt Lark Shoes The Hub LUX Blowdry & Beauty Bar Vine Wine Shop & Bar Mathnasium of San Anselmo West America Bank Peet’s Coffee & Tea

«« What had turned the marijuana marketplace upside down, and did it have to do with the pandemic, I wondered.

David Downs, the California bureau chief at Leafy, assures me that the drought is “real,” that the market is “bifurcated” and that in the illicit world the markup is 90 percent. Still, given the volatility of the cannabis world, that could change as quickly as the Dow Jones.

I decided to play pot detective and uncover the truth about the kaleidoscopic cannabis marketplace. Fortunately, I wasn’t starting from scratch. Ever since February 2020, I’d been visiting dispensaries, farms and manufacturing centers in California and writing my weekly cannabis column, “Rolling Papers,” for the Bohemian and the Pacific Sun. I had clues and hunches and the names and addresses of people and places where I could poke around, ask questions and listen.

At The Galley, a cannabis manufacturing and distribution company in Santa Rosa, I sat down with Annie Holman, the CEO, and Cheriene Griffith, the director of operations, as well as a U.S. Navy veteran and a long time player in the food industry. We were all masked.

Holman and Griffith had weathered the pandemic and survived the storms that had hit The Galley. They were on course, making and delivering (from Modesto to Ukiah) topicals, tinctures, gummies, hard candies, refills for vape pens, beauty products, pre-rolled joints and a variety of chocolates and baked goods.

“It’s a difficult industry to be in,” Holman told me. “We share the pain, perhaps more than any other industry, and band together.”

Last winter it looked like The Galley might sink beneath the waves, but Holman and Griffith rose to the occasion and created a protocol to keep them and

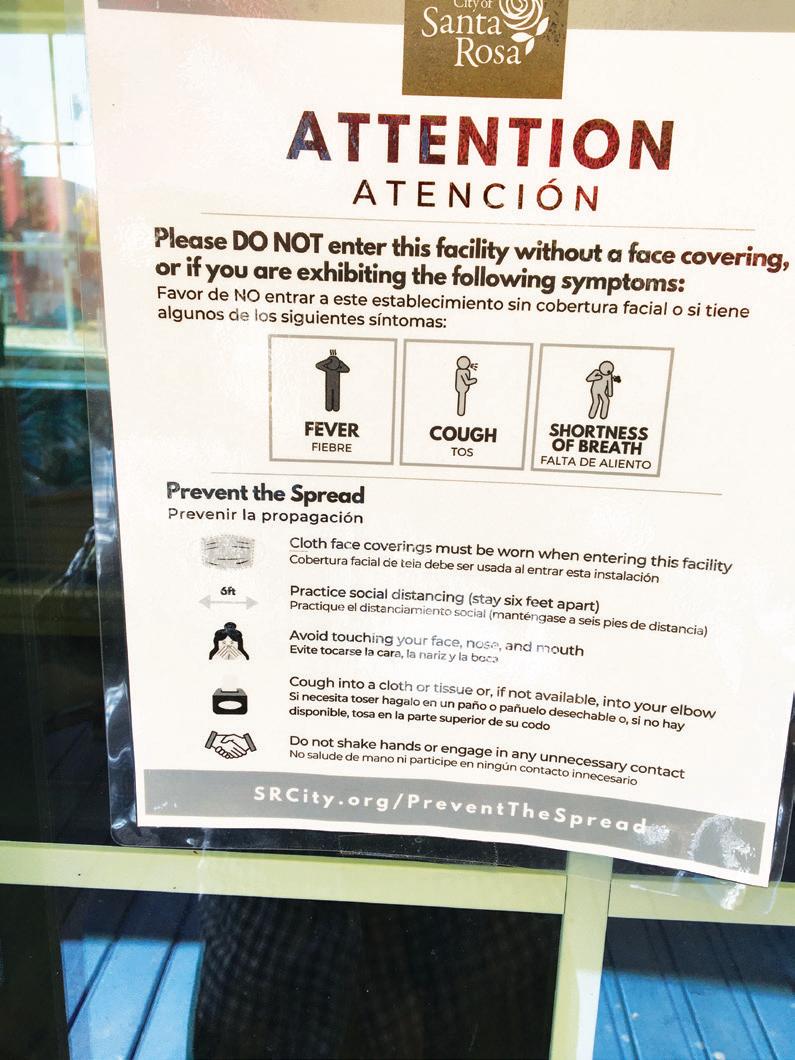

SIGN OF THE TIMES A Covid-19-era flier issued by the City of Santa Rosa.

everyone else aboard the vessel healthy and happy, albeit stressed. There were masks, hand sanitizers, daily health checks before anyone arrived for work, and a log for each and every person to accurately report his or her health. Plus, there was social distancing inside the 8,300-square-foot facility.

Griffith told everyone on the crew, “If you’re sick, don’t come to work.” She and Holman held bi-monthly meetings, talked about their own fears, encouraged workers to share theirs and created a team spirit to combat anxieties. In Southern California, food companies closed after employees tested positive for Covid-19.

“Cheriene saved the day,” Holman told me. “She’s the keel that keeps me straight.”

What saved the company was not only Griffith’s steady hand, but also the ability, soon after the pandemic hit, to transition from making cannabis products to mass-producing hand sanitizers, and with a permit to do so from the city of Santa Rosa.

During a six-week run, The Galley made 45,000 units, registered the product with the Food and Drug Administration, sold a bunch and donated hundreds to the city of Santa Rosa, the homeless and residents of a nursing home.

“We launched that product in tandem with Covid-19,” Griffith told me, showing off a bottle with a label that read “Stop and Sanitize” and depicted a hand and an American flag, as though to say it was patriotic to use hand sanitizer.

About the price of weed, Holman had a theory worth considering.

“A lot of Boomers, who had grown up with ‘Reefer Madness’ and the whole stigma around marijuana, were afraid of going into a dispensary and went back to the black market they knew from the old days,” she said.

Gifted with an uncanny sense of what would sell and not sell, Holman also followed a kind of moral compass that emphasized cooperation rather than competition. During the pandemic, she and Griffith reached out and helped “legacy” growers hard hit by woes, in part because they’d been outlaws who had cultivated illegal weed for years and even decades and had trouble adjusting to the brave new cannabis world of fees, taxes and environmental rules enforced with guns by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“All through the pandemic, we deposited money with the Bank of America and Chase and haven’t had a problem,” Holman said. “Though we haven’t deposited large amounts of cash.” » »

— ANNIE HOLMAN, THE GALLEY

«« That kind of candor about baking is rare in the marijuana industry.

Erich Pearson, the CEO at SPARC, deposits cash in a financial institution, though he hasn’t told me which one because he’s concerned that if word gets out, scores of growers will show up with their cash at the same branch and his account will be closed. A legacy grower himself, Pearson has taken big risks and made a more or less smooth transition to the legal market. When I showed up at his farm in Sonoma Valley at the end of July, the crew had just finished harvesting tens of thousands of mature plants. The pandemic hadn’t prevented the harvest from taking place, nor had it hindered the men who were putting thousands of cannabis starts in the ground.

Perason took one look at the crew and said, “None of these guys have papers. We help them and they help us. It’s a good deal.” Illegal labor, illegal crops and illegal chemicals: that’s the story of much of California agriculture.

While Pearson didn’t have an economic theory, he told me there was a drought and that black-market weed was worth more than legal weed.

Two days later, I watched a 60 Minutes segment about Emerald Triangle cannabis and heard the reporter say that she had visited a garden with 40 plants, that marijuana was harvested only once a year and that the price per pound had dropped drastically.

No one knows better how false and misleading those statements are than a friend, whose real name I would rather not provide since he was recently robbed at gunpoint outside his San Francisco dispensary. Let’s call him Ali Baba. He’s from the Ali Baba part of the world. In March, thieves took all the money in his wallet, he tells me, though he adds that they didn’t take the $5,000 in cash which he’d stashed in the trunk of his white sedan.

I sat with Ali in the enclosed patio behind his dispensary, where we were joined by a young fellow who looked distinctly Asian.

“Japanese?” I asked.

“We Asians all look alike, don’t we?” he replied and laughed, adding, “Chinese.”

My sources tell me that most Chinese in the cannabiz grow indoors. This fellow grew outdoors and hired day laborers, most of them Latinos and Latinas, to do the heavy lifting.

“Visit me,” he said. “I’m a few hours north of the Golden Gate Bridge. It’s a crazy time. Prices have been going up, and there’s been a real pot shortage, too. I’ve been told no one is making big money, but that’s not true. The pandemic has been a boon to the pot business.”

It has also been a boon to cannabis medicine, and has added to the already ample body of evidence that suggests that cannabis can alleviate headaches, menstrual cramps, PTSD, loss of appetite, insomnia and mental health issues associated with the pandemic, though in a recent article in The New York Times, Jenny Taitz, a UCLA professor in clinical psychology, suggested that using cannabis to deal “with anxiety and uncertainty” was dumb. Taitz argued that those who wanted to “empower” themselves in the midst of the pandemic might try half-a-dozen “quick strategies,” including mindfulness, listening to music and conscious breathing exercises.

None of Taitz’s suggestions would have surprised famed astronomer Carl Sagan, who years ago conducted a cannabis experiment on himself: he got high, kept notes and wrote an essay in which he explained that marijuana enhanced his sense of smell, sight, touch and taste. Sex was never better, food never tastier, music never more beautiful, he wrote. Sagan didn’t publish his findings for fear that he and his work would be ridiculed. Were he alive today, Sagan would join the connoisseurs who have come out of the cannabis closet during the pandemic.

During my detective work, when it felt at times like the world was ending, and my own fears were rising, I didn’t solve all the mysteries of the kaleidoscopic marijuana marketplace, but I went home with samples. The cannabisinfused chocolates from The Galley were the best. I followed Annie Holman’s suggestion and ate only a small portion. After two hours the weed kicked in, and my anxiety levels dropped. That night I slept more soundly than I had in a month. w