7 minute read

Oz Reform Debate

AUS’: THE REFORM DEBATE

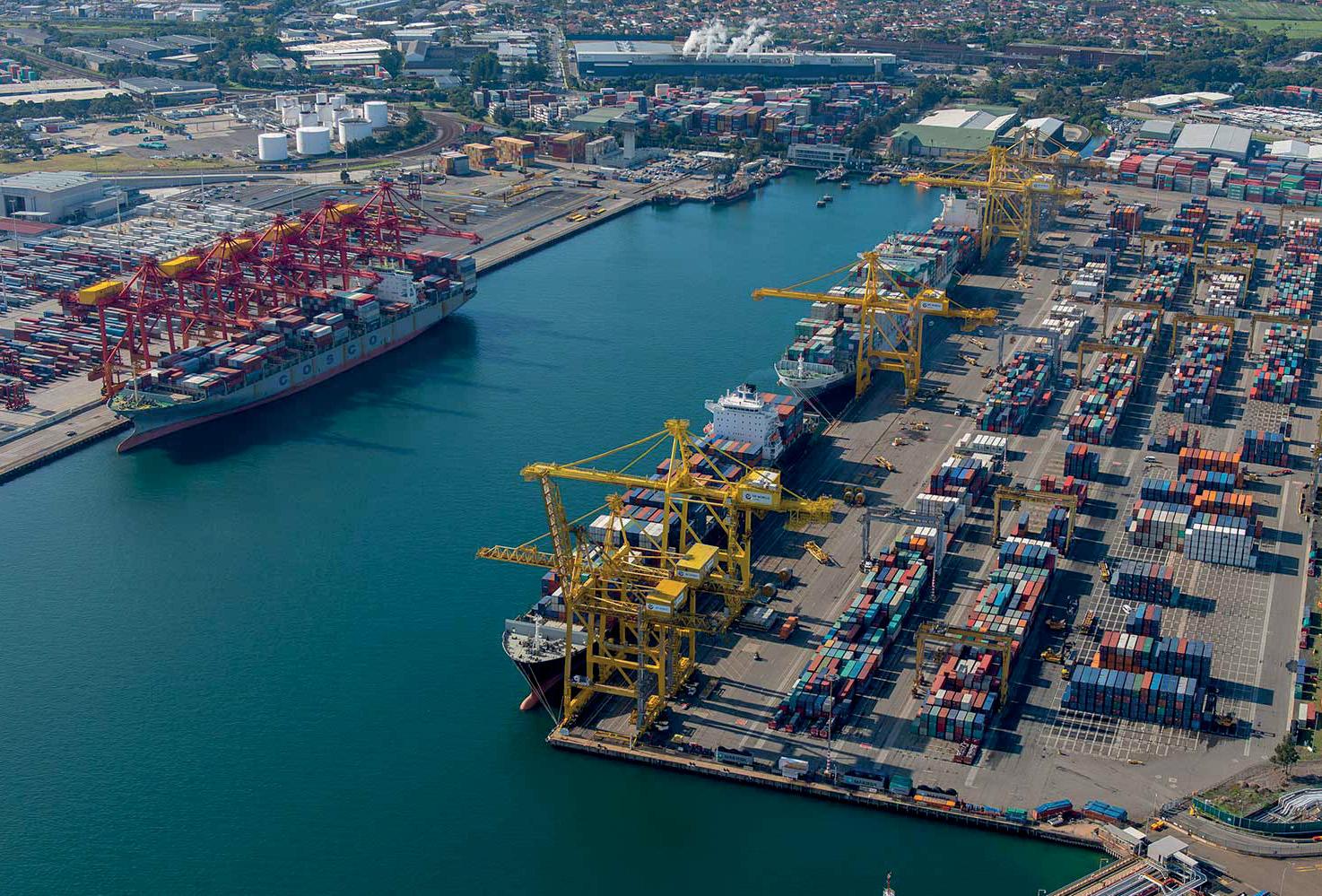

A new report from Australia’s Productivity Commission adds fuel to the fi re of proposed maritime sector reforms – the battle lines are being drawn. Mike Mundy reviews the pros and cons

There is an interesting article that has recently been posted on the website of Shipping Australia, the industry representative body, the focus of which is vulnerabilities in supply chains. It is written by economist Catherine de Fontenay of the University of Melbourne and provides insight into the report which she co-authored on behalf of the Productivity Commission aimed at identifying signifi cant vulnerabilities in the supply chain and, importantly, ways of dealing with them. The origins of the report go back to Treasurer Josh Frydenberg who initiated the Productivity Commission’s work in this area following the impact of COVID-19 which, particularly when it fi rst hit, exposed supply chain vulnerabilities.

There is a common perception that Australia is potentially more open to supply chain problems due to the extended distances over which most import and exports– containerised and others – move. The Productivity Commission’s report, formally entitled Vulnerable Supply Chains and released on 13 August 2021, does not, however, identify this as a major factor. The research undertaken was empirical – fact driven – and basically sees the main impediment to the effective performance of supply chains as due to “market concentration” related to supply, which it says creates vulnerability.

The approach taken to examining the cause of such problems, which basically first raised their head in conjunction with the supply of products such as sanitiser and masks, was to undertake “a broad scan of data,” a macro look. Catherine de Fontenay explains: “Our approach was to first identify the products that were vulnerable to supply chain disruptions and then to identify which of them were used in essential industries.”

She elaborates: “Australia imported 5862 different products from 223 countries in 2016-17. The biggest suppliers were China and the United States. Combined, they accounted for just over one third of the value of goods imported. We found that 1327 of the 5862 products – one in five – came from concentrated import markets”

The most concentrated commodities were chemicals, iron and steel, and equipment. Other products such as seafood and some types of clothing were also identified as concentrated.

The next step was to consider how markets were likely to respond to a disruption of supply or spike in demand. It was concluded that “…shortages trigger a period of uncertainty during which existing contracts and personal relationships help determine who gets goods first.

“But fairly soon after, who gets what is determined by the prices buyers are willing to pay.”

Hence the conclusion arrived at was that: “…a product is vulnerable if much of the world supply is concentrated in one country; if that country experiences a natural disaster or other shock, the remaining world supply is very limited, and prices will be astronomical.”

The report determines that China is the main supplier of vulnerable products to Australia, approximately two thirds of the goods identified as such. Yet many of the imports

8 There are pros

and cons on both sides of the reform argument but is the strong hand of government an appropriate vehicle to bring about meaningful reforms?

classified as vulnerable “are not critical to the wellbeing of Australians.” The essential supplies that were specified as susceptible basically boiled down to personal protective equipment and certain chemicals.

So how does knowing all this help, what action can be taken to minimise or eliminate supply chain problems?

REFRESHING CONCLUSION

Two main conclusions are drawn from the report Vulnerable Supply Chains.

The first is that onshoring cannot always help. As Catherine de Fontenay notes: this: could not have prepared us for a tenfold spike in demand for personal protective equipment unless we produced multiples of what we needed.” And similarly, taking the case of the Pfizer vaccine, “this would still require importing 280 components from 19 countries, some of which are the true source of scarcity according to Pfizer.”

The second conclusion is a refreshing and practical one: namely, that government should be responsible for managing their supply chains (for example with hospitals), and private firms should be responsible for theirs. Specifically, no major scope is seen for government intervention across the board… “…government should intervene in private markets only when the private firm is more tolerant of risk than the nation.”

The conclusion is refreshing because in so many respects Australia is now the focus of calls for government intervention of one form or another. “As one industry observer puts it, Australia is building a reputation for taking the English bureaucracy of the old days to a new level.”

Indeed, this is not a problem that has gone unnoticed previously with many tomes initiated on the subject even from much earlier days when papers such as Fighting Australia’s Over Regulation were circulated. This carries on its cover page the well-known quote from Thomas Jefferson, “He who governs least, governs best,” as a hallmark of its thinking.

HOT ISSUE

The hot regulatory issue at the moment in Australia’s maritime sector is the Freight Trade Alliance (FTA) and Australian Peak Shippers Association (APSA) backed call for a formal shipping review and introduction of a Federal Maritime Regulator. This view, however, is countered by Shipping Australia which does not view such steps as appropriate. All three industry representative bodies understandably take positions which they say reflect the views of their members.

FTA/APSA’s view of the requirement for a shipping review and introduction of a Federal Maritime Regulator is based on what it sees as the necessity of protecting the Australian trade sector – importers, exporters, freight forwarders and cargo owners.

A central feature of the two bodies argument for a shipping review is that Part X of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010, which they say gives shipping lines access to a “wide suite of exemptions from competition law,” needs comprehensive reform. The alternative idea is promoted of a class exemption regime, “with terms to be drawn as narrowly as possible to permit the desired activities to be operationalised.”

“A class exemption,” they explain at some length, “is a way for the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) to grant a business exemption from competition law for certain ‘classes of conduct’ that may otherwise carry a risk of breaching competition laws, but do not substantially lessen competition, and/or are likely to result in overall public benefits.” As envisaged, “it would operate alongside the ACCC’s existing ‘authorisation’ and ‘notification’ processes, in which a business that falls outside the class exemption could still seek a legal protection on a case-by-case basis.”

The call for a Regulator is postulated against an environment of what is described as limited shipping capacity, operational disruption, restricted access to market and rapidly increasing costs.

With both initiatives opposing parties raise the spectre of ever-increasing regulation tying the hands of parties in the logistics chain so that they are unable to act in a commercial manner to the detriment of the respective services they provide. The prospect of ever creeping regulation is not one that is accepted on a universal basis – terminal operators for one.

The point is made by more than one party that the architecture of Australia’s regulatory apparatus is such that it already generates significant critical mass – Federal (Parliament), State and territory parliaments and local councils all operate as engines of regulation.

For its part, Shipping Australia states with regard to shipping reform that the regulation of its members is not required as there are multiple entities openly competing – i.e. market forces at work.

TIME FOR CHANGE?

Much of the current push for shipping reform and introduction of a Federal Maritime Regulator has been borne out of the turgid time Australia has endured under the influence of COVID-19. There is, however, a fundamental question to ask in this respect: has what the country has endured, and to some extent continues to be impacted by, been so much worse than the experience of other countries? There is common experience visible and as such it begs the question, is it appropriate to leverage significant regulatory/ governance change against this non-normal background?

Admittedly, the exceptional factor in Australia has been ongoing port labour related problems but looking back down the years these are hardly totally surprising.

The words of Thomas Jefferson are perhaps worth reflecting on!

8 Is the current climate the right one in which to frame maritime policy reforms?