10 minute read

MSO Livestream: Scheherazade

Scheherazade

Monday 16 March | 7pm

Recorded at Arts Centre Melbourne, Hamer Hall

BLOCH Schelomo

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Scheherazade

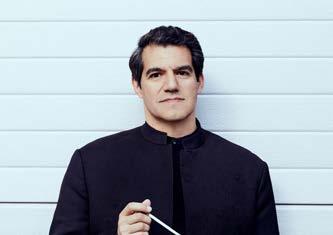

Miguel Harth-Bedoya conductor

Peruvian conductor Miguel Harth-Bedoya is a master of colour, drawing idiomatic interpretations from a wide range of repertoire in concerts across the globe. He has amassed considerable experience at the helm of orchestras with 2019–2020 his seventh season as Chief Conductor of the Norwegian Radio Orchestra and his 20th season as Music Director of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra. Previously he has held Music Director positions with the Auckland Philharmonia and Eugene Symphony.

With his experienced toolkit and exceptional charisma, Harth-Bedoya has nurtured a number of close relationships with orchestras worldwide and is a frequent guest of the Helsinki Philharmonic, MDR Sinfonieorchester Leipzig, National Orchestra of Spain, Atlanta Symphony, New Zealand Symphony and Sydney Symphony Orchestras. With a passionate devotion to unearthing new South American repertoire, Miguel Harth-Bedoya is the founder and Artistic Director of Caminos Del Inka, a non-profit organisation dedicated to researching, performing and preserving the rich musical legacy of South America.

ERNEST BLOCH (1880-1959)

Schelomo – Hebraic Rhapsody

Timo-Veikko Valve, cello

Ernest Bloch was not a modernist. Neither was he a serialist, an experimentalist, a revisionist, a minimalist, nor a ‘jazz freak’. He arguably therefore holds a unique position in twentieth-century music. If it were absolutely necessary to pigeonhole his work in some way, he could be described as a product of the height of the Romantic era, who continued to develop innovatively within that broad framework, undeterred by the more radical approach of his colleagues.

Legend has Bloch, aged ten, vowing to become a composer, and formalising his written vow by ritually burning it. Throughout his life he viewed creativity as a serious matter, requiring hard work and personal dedication to the subject or artistic idea. Most of Bloch’s major works (including Schelomo) have strong connections with his Jewish faith, both in subject matter and musical idiosyncrasies. His melodies and themes often carry the flavour of his family background: even when they are not direct quotes from Jewish sources, they come from what Bloch described as ‘the age-old inner voice’. So perhaps it is possible after all to categorise him, as a ‘Nationalist’ composer of the Jewish nation, in the same way in which Bartók is associated with Hungary.

Despite early lessons with Jacques Dalcroze and violin studies with Ysaÿe, the young Bloch, married and not wealthy, seemed to be ambling gently towards life in the family clock business. Eventually, music won the day, as he became increasingly involved with composing and conducting in his native Geneva and then further afield. The New World beckoned in 1916, and Bloch, although making several trips home over the years, found his niche in the United States. He held several high positions in tertiary institutions. Roger Sessions is perhaps the best known of his pupils, who are chiefly remarkable for their individuality – a mark of a fine teacher, and one which Bloch shared with that other famous nurturer of composers, Nadia Boulanger.

There are two different stories about how Ernest Bloch came to write Schelomo. They are not mutually exclusive; there is probably truth in both. The first has the thirty-sixyear- old composer, still in Geneva, wrestling with the words of Solomon (‘Schelomo’ in Hebrew), trying to write a vocal work but encountering difficulty with the relatively unfamiliar language. His friend Alexandre Barjansky, a fine cellist, suggests reworking the sketches into a piece for cello and orchestra. The second story has Barjansky again asking for a work for cello. Bloch’s eye alights on a wax figurine of Solomon, made by Barjansky’s wife Catherine, a sculptor. Inspired, he completes Schelomo. Whatever the case, Bloch dedicated the work to both Barjanskys for their part in its creation.

What is certain about both these stories is that Bloch was initially interested in using the text of the Book of Ecclesiastes, usually attributed to Solomon, and in particular the dark texts which surround the most famous quote: ‘Vanity of vanities; all is vanity…I have seen all the works that are done under the sun; and behold, all is vanity and vexation of spirit.’ Other writers have also detected elements of the more famous and sensual Song of Solomon in certain musical figures. As noted in the Old Testament, Solomon had ‘…seven hundred wives of royal birth and three hundred concubines, and his wives led him astray’. (Elsewhere, the projected number of wives is a more reasonable thirty-five).

The sub-title of ‘Hebraic Rhapsody’ is also significant. Not only does it highlight the essential Jewish core of the work, but Rhapsody (from the Greek, literally meaning ‘stitched together’) implies an expressive freedom born of strong emotion. Strict form is not the foundation of this work. Its power lies in the horrors of the First World War and their parallels with Old Testament bloodletting, expressed in a direct manner that mirrors the illogical progression of troubled thoughts. Schelomo is sometimes characterised as a lesser work in the cello repertoire, perhaps because it lacks the crucial word ‘concerto’ in its title – but surely no one who truly appreciates its subject matter and the date and circumstances of its composition could remain unmoved by its beauty and sincerity, or unimpressed by the considerable technical demands on the soloist.

Although Bloch went on to write other works on Jewish subjects (the Israel symphony; Voice in the Wilderness – his other major work for cello and orchestra; Psalms), Schelomo is probably the piece that drew most heavily on the composer’s background. Jewish-style popular and religious melodies appear, as do motifs reminiscent of shofar (ram’s horn) cermonial calls. Even the instrumentation occasionally seems deliberately coloured to suggest Jewish origins: the solo oboe plays a prominent part, as do solo violins. Use of augmented intervals of seconds and fourths imply ‘The East’ to Western ears. Similarly, a harmonic structure based on fourths and fifths – such as that which underpins Schelomo – implies a foreign-ness or antiquity alien to the triadic harmony of Mozart, Beethoven and so on.

A number of works by Bloch give the cello a role not dissimilar to its vocal equivalent, the cantor in the synagogue. Bloch did not intend this work to be programmatic. However, he did allow that ‘If one likes, one may imagine that the voice of the solo cello is the voice of the King Schelomo. The complex voice of the orchestra is the voice of his age, his world, his experience…’.

Dotted rhythms and yearning semitones predominate the first half of the work. The brass section takes on a military flavour when it is given the chance (a far from irrelevant matter in a work dated 1916). The solo cello, introduces motifs and inspires the orchestra to ever-greater heights, depths and dynamics – but it dies, at the end, lonely in its grief. To give Bloch the final word: ‘This work alone concludes in complete negation. But the subject demanded it!’

Katherine Kemp Symphony Australia © 1998

NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844–1908)

Scheherazade – Symphonic Suite, Op.35

Largo e maestoso – Lento – Allegro non troppo (The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship)

Lento (The Story of the Kalender Prince)

Andantino quasi allegretto (The Young Prince and the Young Princess)

Allegro molto – Vivo – Allegro non troppo e maestoso – Lento (Festival at Baghdad – The Sea – The Ship Goes to Pieces on a Rock Surmounted by a Bronze Warrior – Conclusion)

Rimsky-Korsakov conceived the idea of a symphonic suite based on episodes from Scheherazade in the middle of winter 1887–88, while he and Glazunov were engrossed in the completion of Borodin’s unfinished opera Prince Igor. The following summer he completed the suite – ‘a kaleidoscope of fairytale images and designs of Oriental character’.

‘All I had desired,’ he later wrote in My Musical Life, ‘was that the hearer, if he liked my piece as symphonic music, should carry away the impression that it is beyond doubt an Oriental narrative describing a motley succession of fantastic happenings and not merely four pieces played one after the other and composed on the basis of themes common to all the four movements. Why then, if that be so, does my suite bear the name, precisely, of Scheherazade? Because this name and the title The Arabian Nights connote in everybody’s mind the East and fairytale wonders; besides, certain details of the musical exposition hint at the fact that all of these are various tales of some one person (who happens to be Scheherazade) entertaining there with her stern husband.’

Rimsky-Korsakov considered Scheherazade one of those works in which ‘my orchestration had reached a considerable degree of virtuosity and bright sonority without Wagner’s influence, within the limits of the usual make-up of Glinka’s orchestra’. So formidable is his instinct, that with surprisingly modest forces (adding to the traditional orchestra only piccolo, cor anglais, harp and percussion) Rimsky-Korsakov can convince his listeners of the raging of a storm at sea, the exuberance of a festival, and the exotic colour of the Orient.

As if repeating in music Scheherazade’s feat of narrative woven from poetry and folk tales, Rimsky-Korsakov drew on isolated episodes from The Thousand and One Nights for his suite. At first he gave the four movements titles drawn from these narratives. But he soon withdrew the headings, which, he said, were intended to ‘direct but slightly the listener’s fancy on the path which my own imagination had travelled, and to leave more minute and particular conceptions to the will and mood of each’.

According to the composer, it is futile to seek in Scheherazade leading motifs that are consistently linked with the same poetic ideas and conceptions. Instead, these apparent leitmotifs were ‘nothing but purely musical material… for symphonic development’. The motifs unify all the movements of the suite, appearing in different musical guises so that the ‘themes correspond each time to different images, actions and pictures’. The ominous octaves representing the stern Sultan in the opening, for example, appear in the tale of the Kalender Prince, although Shahriyar plays no part in that narrative. And the muted fanfare of the second movement returns in the otherwise unconnected depiction of the foundering ship.

Rimsky-Korsakov did admit, however, that one of his motifs was quite specific, attached not to any of the stories, but to the storyteller: ‘The unifying thread consisted of the brief introductions to the first, second and fourth movements and the intermezzo in movement three, written for violin solo and delineating Scheherazade herself as telling her wondrous tales to the stern Sultan.’ It is this idea – an intricately winding violin theme supported only by the harp – which soothes the thunderous opening and embarks upon the first tale: the sea and Sinbad’s ship. For Rimsky-Korsakov, who was synaesthesic, the choice of E major for the billowing cello figures can have been no accident: his ears ‘saw’ it as dark blue.

A cajoling melody played by solo bassoon represents a Kalender (or ‘beggar’) Prince in the second movement. The similarity between the two main themes of the third movement (for violin and then flute and clarinet) suggests that the Young Prince and Princess are perfectly matched in temperament and character.

An agitated transformation of the Sultan’s theme, in dialogue with Scheherazade’s theme, prefaces the final tale. The fourth movement combines the Festival in Baghdad and the tale of the shipwreck, described by one writer as a ‘confused dream of oriental splendour and terror’. Triangle and tambourines accompany the lively cross-rhythms of the carnival; and the mood builds in intensity before all is swamped by the return of the sea theme from the first movement. But after the fury of the shipwreck, it is Scheherazade who has the last word. Her spinning violin solo emerges in gentle triumph over the Sultan’s bloodthirsty resolution.

Yvonne Frindle © 1998/2009