44 minute read

Soul enterprise

From refugee camp to boardroom

Mark Sheerin’s two worlds couldn’t be farther apart. Previously he served Sudanese refugees as a Christian aid worker; now he is part owner of a financial planning and wealth management firm in Atlanta, Georgia.

Advertisement

“The distance between my two worlds — my former life as an international aid worker, and my current life serving some of the world’s most financially fortunate — seems unbridgeable some days. On other days, the two worlds look more similar than I imagined,” he writes in “Why I left World Vision for finance,” an online feature of Christianity Today.

“I used to define my World Vision job as bringing opportunity to the poor so they might thrive. I used to define my new job in finance as providing guidance to people so that they could make the most prudent decisions to meet their goals and leave legacies. Now I describe both my careers in the same way: creating redemptive spaces in a fallen and tangled world.”

He gained perspective on the clash after hearing a sermon on Jeremiah 29 where Jewish exiles in Babylon are told to “seek the peace and prosperity of the city.” The Jews were being called to cling to holiness while still embracing the city, and in that seeming contradiction Sheerin found a bridge between two divergent careers. “God calls his people to seek the redemption of particular spaces in each and every context,” he writes. “For the Jewish exiles, this meant living holy lives in a pagan city. For my own life, it meant leaving explicitly Christian ministry and seeking the well-being of Atlanta by lashing myself to the mast of this city’s ship.”

Sheerin now realized that Jesus had come to earth to radically reconcile all things to himself, to redeem institutions, individuals, the realms of justice and law, education, farms, cities, even the world of finance.

He says the decision to leave the refugee camp for the boardroom was complicated. “How could I justify trading a vocation of serving the poor for a career among the wealthy? Believing that finance and feeding starving children both amount to good work in God’s eyes still challenges me on my best days. But then I remember Jesus’ mission to conquer sin and its effects in all its forms and in every place. Fighting against economic injustice through World Vision or through a financial planning firm are both mandated by God. Both tasks are valuable, both tasks seek redemption of broken systems and fallen people. Instead of digging wells, my firm walks with widows through the jungle of probate. Instead of sponsoring children, my firm partners with families through difficult, end-of-life decisions.”

Sheerin adds, “Striving to create a place where the financial industry can be a balm rather than a scourge seems as daunting a task as feeding the hungry in Africa.”

Spiritual growth — at work

Everyone knows the marketplace is a place to utilize our skills and earn a living. Can it also be a place of spiritual growth?

Absolutely, say Richard J. Goossen and R. Paul Stevens in their new book, Entrepreneurial Leadership: Finding Your Calling, Making a Difference (InterVarsity, 2013). They offer three ways in which the marketplace is a location for spiritual formation. 1. It’s the place where we show who we really are. “Our inside is revealed by what we do outside, by the way we work, by our relationships with people, by the realities of how we go about doing day to day enterprise.” 2. “The seven deadly sins, seven soul-sapping struggles that include pride, greed, lust, anger, envy, sloth and gluttony are revealed not in quiet times and prayer retreats but in the thick of life, in business meetings, as we struggle over this month’s sales, when we have to deal with an awkward customer or employee. And every soulsapping struggle becomes an opportunity to grow spiritually.” 3. Good work is part of God’s creating and sustaining plan for the world. “We are actually partners with God in our daily work.... This brings a transformative dimension to our daily work. It means that instead of regarding work in the world as a diversion from the spiritual life and from the ‘work of the Lord’ ... we are doing ‘the Lord’s work’ in creating new products and services, engaging in trading and global enrichment, creating new wealth and improving human life.”

Over the fence, out of the park

You may have heard about or seen the movie “42,” which depicts how Jackie Robinson became the fi rst African-American in Major League Baseball. What it doesn’t fully portray is how the young athlete and his boss made history by bringing their Christian faith to work.

Branch Rickey was the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers and founder of the minor league system. When it came to racial integration he also had a social conscience. He hired Robinson at a time when black players were confi ned to their own league, no matter how good they were.

At the center of this dramatic civil rights story were “two men of passionate Christian faith,” writes Eric Metaxas in Seven Men: And the Secret of Their Greatness. “Robinson was a Christian [and] his Christian faith was at the very center of his decision to accept Branch Rickey’s invitation to play for the all-white Brooklyn Dodgers.... Branch Rickey himself was a Bible-thumping Methodist whose faith led him to fi nd an African-American ballplayer to break the color barrier.”

Other baseball owners were aghast. Two teams threatened to go on strike if Robinson took the fi eld.

Rickey held fi rm, and Robinson joined the Dodgers the day before the opening of the 1947 season.

As recounted by baseball writer Roger Kahn in his book Into My Own: The Remarkable People and Events That Shaped a Life, Rickey posed a hard condition on his new rookie. He warned Robinson he would suffer abuse, and made him promise not to respond in kind.

“A man disinclined toward understatement, Rickey cited as an acceptable role model Jesus Christ,” Kahn writes. “When Robinson asked if Rickey wanted someone without the courage to fi ght back, Rickey’s response shook down thunder. ‘No, I want somebody with the courage not to fi ght back.’”

Remaining nonviolent wasn’t easy. When Robinson came to bat, pitchers tried to bean him. Other players tried to spike him when he played fi rst base. He’d hear racial slurs yelled from the opposing dugout.

Robinson kept his pledge and did not respond. He ended up playing 10 seasons and is still ranked among the best baseball players ever.

By bringing their faith to work, Rickey and Robinson changed a lot about America — not the least of which, its national pastime.

Serve time, serve coffee

Pete Leonard has a passion for coffee and convicts. He has brought both of them together by starting a roasting company to employ ex-cons who can’t fi nd jobs.

Back in 2007 Leonard observed two seemingly disparate realities — the U.S. is the world’s leading consumer of coffee (45 million pounds a year), as well as a global leader in prison population (2.2 million people).

He also learned that ex-convicts have a lot of trouble getting jobs, which can lead them back into crime. In his state of Illinois, 35,000 convicts get out of prison each year, but almost half (47 percent) end up back in a cell. Having a job plays a huge role in keeping them straight.

Leonard and two friends decided to satisfy their coffee cravings by starting Second Chance, a high-end roaster that sells under the label I Have a Bean. They also decided they would hire people who had served time. Today, seven out of their 10 employees are ex-inmates. A former co-owner of a software company, Leonard says this gig is “the hardest, the most fulfi lling, and the most fun — all at the same time.” His ambition: set up 150 micro-roasting plants across the U.S. and become “the largest postprison employer in the world.” — Christianity Today

Overheard

“I don’t believe in just ordering people to do things. You have to sort of grab an oar and row with them.” — U.S. businessman Harold Geneen (1910-97)

Looking ahead

New three-year plan charts course to serve 28 million clients by 2016

We have taken risks to create innovative products that provide sustainable livelihoods to the poor, and tested and modeled these products through entrepreneurial partnerships. Much of what we have achieved is now part of mainstream development programming among government, non-government and business organizations around the world.

This three-year strategic planning document reviews what worked well in the past three years, and identifi es the most promising opportunities given economic and development trends and our own strengths and limitations. The 2014-16 cycle is largely a continuation of what has worked well for us.

Areas where we are making a difference:

Agriculture

Despite urbanization more than half of households are still rural in many developing countries, and they remain the most disadvantaged communities in terms of all human development indicators. Further, the world’s demand for food is expected to double in the next 50 years, while the natural resources that sustain agriculture will become increasingly scarce, degraded and vulnerable to the effects of climate change. MEDA will build on its experience in agricultural development to deliver scalable, replicable, market-driven solutions that enable millions of small farmers to compete profi tably in local and global markets.

Every three years MEDA undertakes a detailed planning exercise to lay out marching orders for the next stage of creating business solutions to poverty. The new plan, covering 2014 to 2016, spends 66 pages to review our performance for the past three years, analyze strengths and weaknesses, examine industry trends and plot direction for the new cycle, which takes effect in Fiscal Year 2014 (starting July 1, 2013). Following is a condensed summary: What we’re doing: • Ukraine — helping 7,000 farmers work together to produce better and more profi table crops • Ethiopia — increasing incomes among 8,000 rice farmers and 2,000 weavers • Techno-Links (Peru and Nicaragua) — helping commercially distribute affordable, climate-smart equipment (drip irrigation, tillage, etc.) to 5,000 small farmers • Tanzania — developing commercial supply chains for disease-resistant varieties of cassava seed stems for 18,000 farmers • Sierra Leone — helping Mountain Lion Agriculture, a Canadian venture, to expand its small farmer rice-paddy out-grower model to benefi t 5,000 farmers

What’s next for 2014-16:

• Partnerships with global food fi rms (think Walmart and Unilever) to integrate more small farmers into their supply chains • Apply our cassava seed project experience to develop other commercial seed systems • Phase 2 of our highly successful Ukraine Horticulture Development Project

Inclusive fi nancial services

In addition to the improved incomes that can be realized from more productive smallholder agriculture, off-farm incomes are vital to reduce rural poverty, create opportunities for women and youth, stem migration to

Trends are promising...

Extreme poverty is falling in every region. For the fi rst time since poverty trends began to be monitored, the number of people living in extreme poverty and poverty rates fell in every developing region — including in sub-Saharan Africa, where rates are highest. The proportion of people living on less than $1.25 a day fell from 47% in 1990 to 24% in 2008 — a reduction from over two billion to less than 1.4 billion.

The world has met the target of halving the proportion of people without access to improved sources of water, with the proportion of people using an improved water source rising to 89% in 2010. Between 1990 and 2010, over two billion people gained access to improved drinking water sources, such as piped supplies and protected wells.

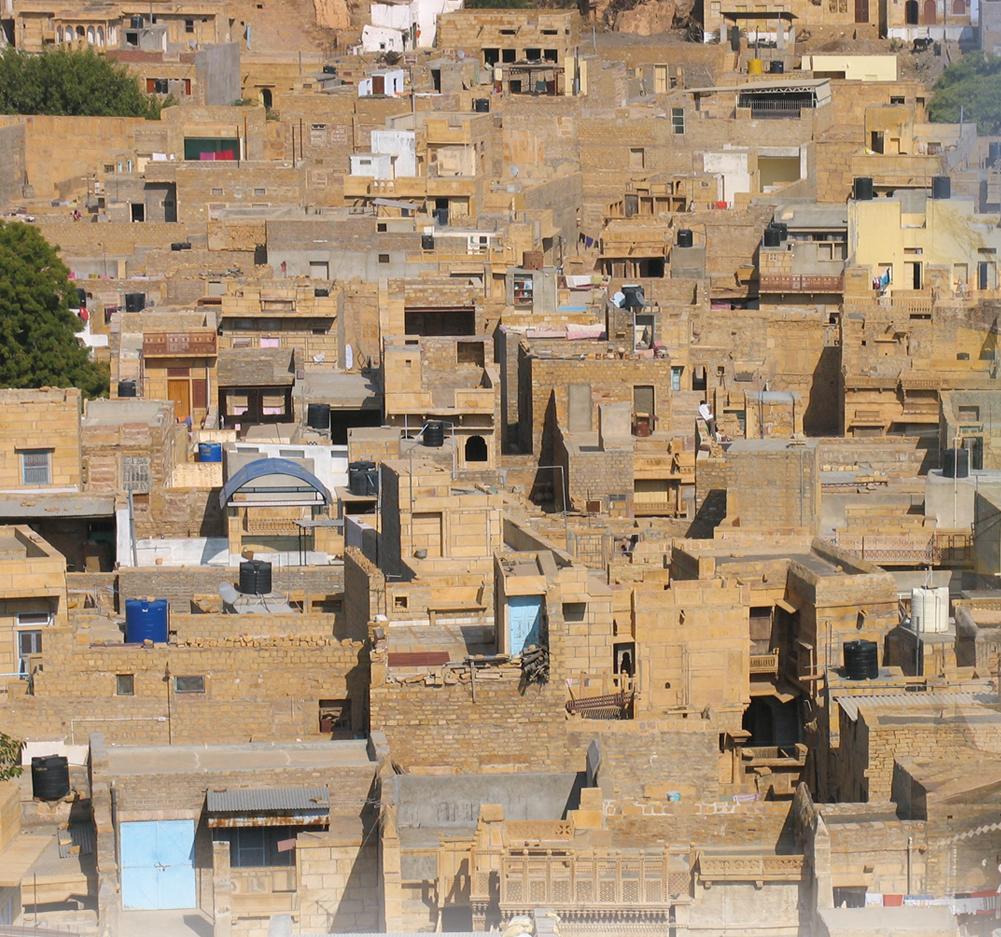

Improvements in the lives of 200 million slum dwellers exceeded targets, while the share of urban residents in the developing world living in slums declined from 39% in 2000 to 33% in 2012. More than 200 million gained access to either improved water sources, improved sanitation facilities, or durable or less crowded housing.

Child survival progress is gaining momentum. Despite population growth, the number of under-fi ve deaths worldwide fell from more than 12 million in 1990 to 7.6 million in 2010.

Global malaria deaths have declined. The estimated incidence of malaria has decreased globally by 17% since 2000. Over the same period, malaria-specifi c mortality rates have decreased by 25%. Reported malaria cases fell by more than 50% between 2000 and 2010 in 43 of the 99 countries with ongoing malaria transmission. ◆

worldwide, and it is estimated that an extra 10 phones per 100 people in a typical developing country boosts GDP growth by 0.8 percentage points.

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) represent a rapidly growing but still very small proportion of the economies of Low Income Countries. SMEs provide valuable jobs, important markets for low-income producers, and provide essential inputs to increase the productivity and well-being of the poor. This sector offers opportunities for investment and increased engagement in providing value chain services to the poor.

Climate change is increasingly, and disproportionately, impacting the poor in many countries. Rising sea levels due to increased surface temperatures may affect as many as 600 million people living in low-lying coastal zones. Agriculture will be signifi cantly affected by more drought and fi res. Intensifi ed weather patterns are creating more frequent and stronger storms, leading in many cases to disasters.

Terrorism continues to be a real threat to development around the world, not just against the west or western players in development. With high youth unemployment, the situation may well worsen. Confl ict and terrorism lead to loss of income sources, infrastructure and services; movements of people to other areas or countries; and destruction of land. ◆

But still more work to do

Vulnerable employment (unpaid family workers and own-account workers) has decreased only marginally over 20 years and accounted for an estimated 58% of all employment in developing regions in 2011, down only moderately from 67% two decades earlier.

Hunger remains a global challenge. The most recent FAO estimates of undernourishment set the mark at 850 million people living in hunger in 2006/2008 — 15.5% of the world population. Progress has also been slow in reducing child undernutrition.

Gender inequality persists and women continue to face discrimination in access to education, work and economic assets, and participation in government. Violence against women continues to undermine efforts to reach all goals.

Recent estimates are that 2.5 billion adults, just over half of the world’s adult population, do not use formal fi nancial services to save or borrow. Most of the unbanked live in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East. Of the 1.2 billion adults who do use formal fi nancial services, at least two-thirds live on less than $5 per day, indicating that it is access, not the size of income that matters.

More than fi ve billion mobile phones are now in use

Photo by Steve Sugrim

With locations throughout Zambia, this mobile money provider with whom MEDA works is enabling the poor to participate in the fi nancial system through savings, loans, money transfers and insurance.

overcrowded slums, and diversify rural economies. In almost all cases, however, access to appropriate rural fi nancial services to support these initiatives is non-existent. MEDA has vast experience in providing fi nancial services for micro, small and medium businesses that form part of rural value chains. It aims to work with partners who are eager to expand their services and who can develop innovative, high-quality rural, agricultural and branchless (mobile) fi nancial services and products to help both farm and non-farm businesses to develop the rural economy.

What we’re doing:

• Working with various partners, from banks to mobile money providers, to enable the poor to participate in the fi nancial system through savings, loans, money transfers and insurance • Expanding access to branchless and mobile money products in rural Zambia, Nicaragua and Haiti • Promoting debit cards and branchless banking to fl ood victims in Pakistan • Developing sustainable rural lending products for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Afghanistan • Supporting a Haitian commercial bank to design a branchless banking strategy to reduce service costs and increase convenience and security for clients

What’s next for 2014-16:

• Expand mobile and branchless delivery methods for

Every year 2 million people die from indoor pollution; greener cookstoves would help

fi nancial services to rural households, small farmers and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) • Work with impact investors to strike long-term partnerships and offer technical support to innovative social enterprises in

fi nancial services • Continue Haiti’s post-earthquake recovery by helping a private company to expand its micro-insurance products that help the poor to protect their assets and health • Explore ways to leverage existing value chain relationships to increase fi nancial services access for small businesses and farmers

Impact investment

The power of private equity investment in emerging markets is a well-known MEDA story that goes back to our origins 60 years ago. Sharing that story with private equity markets, harnessing the power of investors to improve the fi nancial performance of companies in emerging markets, and delivering positive social and environmental impact — that is the heart of the impact investment industry in which MEDA seeks to be a leader. In most Low Income Countries the successful small and medium business sector is the “missing middle,” the elusive link in many value chains upon which the poor depend. Investment in the microfi nance sector has stabilized and improved millions of microenterprises in the informal sector worldwide. However, much additional investment is needed in order for many countries to develop the employment, tax and economic base that only the SME sector can provide. MEDA’s own Sarona Risk Capital Fund invests in companies that fi ll this missing middle in microfi nance, agricultural production and processing and other high-value service and production sectors. Through Sarona Asset Management Inc., MEDA creates investment vehicles to attract and invest capital in emerging markets, with a special focus on the SME sector, while providing the economic, social and environmental returns that impact investors require.

What we’re doing:

The Sarona family of funds continues to funnel capital to a vibrant mix of private equity funds that serve the poor. The Sarona Risk Capital Fund has investments in 64 companies that employ 92,000 people and serve more than 14 million low-income clients.

What’s next for 2014-16:

• Attract more debt and equity capital from individuals and institutions to leverage into investments • Support the SME sector through investment in the $250 million second phase Sarona Frontier Markets Fund and technical and mentoring services for fund managers • Seek appropriate partners to create viable retail offerings for smaller impact investors

- LICs - World - HICs

GDP Growth

Emerging & developing economies

World

Advanced economies

Better growth rates and lower government debt levels in Low Income Countries will continue to favor increased investment there, with opportunities for MEDA and Sarona Asset Management Inc. to provide ongoing and increasing leadership in the impact investment fi eld.

Business of health

Sub-Saharan Africa struggles to develop while its economy is disrupted by endemic diseases — HIV, malaria and tuberculosis — as well as extremely high maternal death rates. MEDA’s growing expertise in the business of health provides a double development impact — increased incomes for those who participate in the business as well as economic productivity for households that would otherwise be negatively impacted by disease and death. MEDA has proven that effective public-private sector innovations can provide sustainable delivery of health products and services. Now, it needs to also convince decision makers in the health industry who to date have been largely accustomed to free distribution. MEDA will diversify and grow business of health impact by expanding beyond insecticide-treated bednets, employing new technologies such as e-vouchers, and by adding new countries.

What we’re doing:

• Malaria prevention through insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs) continues, with over 35 million distributed and an estimated 200,000 lives saved. Electronic vouchers for ITNs have rapidly gained acceptance and offer great potential to expand into other health products. • A new venture in family nutrition is testing technical viability and prospects for commercialization of Vitamin A fortified crude sunflower oil in Tanzania

What’s next for 2014-16:

• Explore innovations in micronutrient fortification for a more nourished world, focusing particularly on small and medium enterprises that process locally produced foods for local markets. • Promote improved cookstoves as a green technology (two million people die annually from indoor pollution) • Expand mosquito net program to Ghana and other African nations

Photo by Jillian Baker

Maulid Maulid, deputy manager of Shafii Sunflower Oil Mills, decants sunflower oil in Babati, Tanzania. MEDA is working with small and medium-sized companies including Shafii, to fortify their sunflower oil with Vitamin A.

Youth and financial services

The worldwide youth population is growing, restless and often unemployed. A major contributor to the recent Arab Spring uprisings was the high level of youth unemployment in the MENA region (Middle East and North Africa) — 25.5% in the Middle East and 23.8% in North Africa in 2010. The irony is that while there is a growing unemployed youth population, there are global shortages of skilled workers (31 percent of employers worldwide report difficulty filling positions due to a lack of suitable talent). In addition, youth repeatedly express interest in beginning their own enterprises rather than working in underpaid positions with poor opportunities for advancement. There is also a critical dearth of financial access among young people. Only 12.3% of youth in the MENA region have a formal bank account, the lowest rate in the world. Having a safe place to save or an appropriately structured loan can be a critical stepping stone for youth on their path to entrepreneurship, career development, and/or financial independence.

What we’re doing:

• In Afghanistan thousands of youth have learned new skills in workplaces that are safer and more financially viable • Our successful YouthInvest methodology, providing financial access and literacy to young people in Morocco and Egypt, is being applied in our large-scale consultancies supporting projects in Nepal and eight countries in Sub-Saharan Africa • Partners in Mongolia, Sri Lanka, El Salvador and Uganda are expanding outreach with financial and nonfinancial services to over one million youth through the Practitioner Learning Program, a learning group facilitated by MEDA

Despite more and more unemployed youth, employers cite a global shortage of skilled workers

Photo by Scott Ruddick

What’s next for 2014-16:

• MEDA will build on its experience in Egypt and Morocco to deepen its reputation as an innovator and leader in youth entrepreneurship products and services, serving disadvantaged youth with fi nancial and non-fi nancial services • MEDA will develop more partnerships with international and local organizations to expand delivery of inclusive youth-focused programs, incorporating mobile and branchless technology and social media channels

Deposit mobilization

The microfi nance and banking sectors increasingly realize that savings are critical to sustain households, small businesses and communities — especially for the poor who lack social safety nets. Deposits also provide a diversifi ed, local and stable funding base for the fi nancial institutions themselves. MEDA is increasingly called upon to help microfi nance partners develop new deposit mobilization programs or help them transform into regulated banks. While MEDA intends to continue to lead in savings product development we will also expand our scope to

These Afghan youth are among the burgeoning global number of unemployed youth, many of whom express interest in starting their own enterprises.

offer more sector-wide mechanisms to help partner banks and MFIs build capacity to provide more diverse products and services for the poor.

What we’re doing:

• Developing innovative savings products, marketing strategies and delivery channels (mobile technology) for a new project in Uganda • Rolling out a new fi ve-year, large-scale project in Yemen to manage a capital fund and provide fi nancial and support services for underserved micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) • Refi ning our risk-management frameworks and client-centric products for fi nancial institutions in the Middle East and Africa

What’s next for 2014-16:

• Rename this area of focus to better refl ect its breadth of scope • Leverage the new Yemen project (mentioned above)

to expand access to financial and business support services for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) • Scale up programming to better serve a huge underserved market for savings (three out of four adults in developing and middle income countries do not have bank accounts) • Develop Sharia-compliant loan products for the MENA region (Middle East and North Africa) and other countries focusing on Islamic lending practices • Promote and gain greater recognition for established MEDA approaches in risk management, product development and governance

Photo by Ariane Ryan

Women’s economic development

Gender equality is smart economics, yet around the world women are blocked from fully participating in market systems. Women-headed households still make up the poorest strata of society in most countries. Their potential to contribute to the economic sustainability of their families and community is diminished by barriers that, as MEDA has proven, can be effectively overcome. MEDA intends to increase programming that includes women as respected and valued participants in market systems.

What we’re doing:

• Major projects linking well over 70,000 women to markets in Pakistan have produced greater earnings which translate into healthier families as well as more respect and status in the household and community • A $20 million project is bolstering family nutrition expertise and incomes among 20,000 women in Ghana • An urban gardening project is building food security in Haiti • Women-owned SME strengthening in Libya

What’s next for 2014-16:

• Maintain current programs in Pakistan, Haiti, Libya and Ghana • Increase the inclusion of 90,000 women across at least seven countries (Ethiopia, Liberia, Jordan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Ghana and Haiti) as respected and valued participants in market systems

Our values

• We seek to create, sustain and innovate. • We treat clients, colleagues and partners with respect and dignity. • We promote justice for the poor by helping them develop entrepreneurial skills and seize economic opportunity. • We value partnerships with the poor and others regardless of gender, race, class, ethnicity, nationality or religion. • We carefully manage human, financial and environmental resources by emphasizing accountability, discipline and sustainability. ◆

MEDA’s newest overseas office in Tripoli, Libya. Project coordinator Amani Ogbi (pictured) assists women who work in small and medium enterprises. Engaged and growing association

Akey MEDA strength and competitive advantage is its association of supporters, however a growing and more diversified association is needed. In some regions chapters need to be started or revitalized, and MEDA needs to reach out and engage younger supporters in new and creative ways. MEDA has also been challenged to reach beyond Mennonite circles to other Christian denominations, as well as to young business/professional people who have left the traditional churches but still wish to be involved in a helping mission. The key to expanding its base of supporters will be tangible opportunities for engagement, effective utilization of social media and other communications, and visible results for their financial support.

What we’re doing:

• The number of people engaged in MEDA’s mission continues to grow, with more than 11,000 people in North America and Europe involved (financial support, attend convention and other events, visit MEDA projects, utilize publications and engage at a governance or business advisory level).

What’s next for 2014-16:

• Engage 13,000 people with MEDA’s mission and values in their own workplaces/communities and through connections with MEDA’s programs around the world • Expand engagement with key groups inside and beyond the Mennonite churches in North America (congregations, young adults/students, farmers and other

Profi t op, not photo op

Institutional donors increasingly favor private sector activity in poor countries and rely on public-private partnership mechanisms to alleviate poverty. They are urging corporations and nonprofi ts to work together to leverage skills, experience and technology to create sustainable impact.

A movement toward increased integrity in business continues, as manifested through fair trade, corporate social responsibility and triple bottom lines — placing equal value on fi nancial, social and environmental returns. There is also a growing sense among donors that in order to address poverty we have to help companies fi nd profi t opportunities, not photo opportunities.

Wireless technology is seen not only as a development opportunity but also a way to deliver development aid, such as the worldwide network called the Better than Cash Alliance.

Among private donors, charitable contributions are increasing slowly — up 4% in the U.S. during 2011 (in the same period MEDA’s growth was 65%). A 40-year analysis of giving patterns in the U.S. shows an average annual increase of 6.8%, with declines in recession years.

In general, older donors give more, but young donors (under 35) are said to be the most optimistic about the future and could give more if approached suitably. Social media is seen as the best way to engage this sector.

Members of organizations increasingly demand value for their membership — “what’s in it for me?”◆ professionals, networks of women) • Increase the number of supportive giving units to 3,500 households • Renew faith and business connections with business workshops and church and seminary events workshops and church and seminary events • Increase annual private contributions from $5.7 million to $7.9 million (39% increase) • Expand opportunities to contribute through online giving, Farmer to Farmer Seed Match, family legacy and planned giving • Fully utilize social media outreach (Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Google+ and LinkedIn) • Expand MEDA’s online web community • Pursue cause marMore younger keting opportunities supporters need We believe these strategic directions fi t well to be reached with global economic and development by fully utilizing trends, and allow us to build on our comsocial media petitive advantage — a unique combination of: focusing on the poorest of the economically active; a fl exible, innovative business approach; a reputation for integrity; excellent staff, board and association; and our commitment to partner with or create locally owned and managed partners.

Over the next three years we plan to incorporate three cross-cutting themes in all we do: (1) small and medium enterprise development; (2) increase our use of information and communication technologies; (3) consider the impact of climate change and use more green technologies.

Our hope is that by 2016 we will achieve the following outputs: • 28 million clients via 300 partners; • 13,000 individuals engaged with MEDA, contributing $7.9 million; • investment of $20 million risk capital funds, with $400 million of assets under management; • an annual development budget of $51 million.◆

Child’s play

Simply having fun is underrated as a step to well-being

Is economic development mainly for grown-ups? Or can it also be for children?

After visiting a “failed state” a seasoned development veteran said, “It’s one of the saddest countries I’ve been to. The children don’t laugh.”

That lack of humor among children testifi ed to a deep vein of economic and social misery.

Child play is not a common indicator on the development index. Perhaps it should be.

Four-time Olympic gold medalist Johann Koss

believes play is as important to a child as food, shelter and security. In 2000 he founded Right to Play, an international organization that uses sport and play programs to improve health, develop life skills and foster peace for children. It works in 20 countries where war, poverty and disease are prevalent.

Koss says North American parents grasp the importance of their own kids being able to play but somehow don’t connect the dots when it comes to children in developing countries. He insists play is not a luxury but is critical for child development and a good way to overcome trauma and develop life skills. “You see improvements in health care, education and in confl ict-free environments when you have access to safe play,” he told a Globe & Mail interviewer.

Koss sees a peacemaking component in children’s play. “What we see with child soldiers is a lack of rules due to their upbringing in rebel groups,” he says. “When you go on the playground and teach them the game of soccer, they realize you can’t have fun if you don’t have rules. They become the guardian of the rules. It creates an improved ability to solve confl icts outside of violence.”

Right to Play uses simple games to promote vaccination, malaria treatment and prevention. One game deals with protection from mosquito-borne malaria. Based on the game of tag, small children put their hands over their heads to symbolize mosquito netting. They can’t be tagged by a “mosquito” as long as the “net” is over their head. “They go home to the parents and say, ‘Where’s my net? I don’t want to be infected because I want to play tomorrow’.” Koss says the game has led to greater mosquito net usage. “In Uganda, we did a study of our children and 85 percent were sleeping under the nets at night, while the national average is 10 percent.” For MEDA, children’s welfare has been a focus of activity in places like Egypt, where it promoted education and safety in family shops, and in Afghanistan where it worked with young apprentices who hoped to someday launch out on “Children should be playing, not work- their own. ing,” says MEDA colleague Mulu Haile, A new project adds that agenda to whose organization uses the sign shown. MEDA’s current work among farmers and

weavers in Ethiopia.

Although the country’s existing policies and legislation aim to protect children from exploitive labor and support their education, child labor is still very high. Most is in the informal sector, where it is diffi cult to enforce safe practices.

Some 18 million Ethiopian children aged 5-17 work — almost a third of the population. More than half of rural children work, many up to 33 hours a week.

E-FACE (Ethiopians Fighting Against Child Exploitation) seeks to reduce the vulnerability of child laborers in the textile and agriculture sectors.

Weavers: Children who work with weavers, spinners and dyers often do so in poor conditions, earning less than $1 a week and working 14-hour days that prevent them going to school. They risk physical deformities from bending over the loom, eyesight problems due to poor lighting, and skin diseases from unsanitary conditions.

Working through local partners, MEDA offers weavers a hazard awareness program called Keep Safe, and a referral system to get children into safer kinds of work or back in school. E-FACE also offers business owners loan incentives to improve workplace conditions and upgrade antiquated looms. MEDA links rural textile families to high-end markets so they can improve their quality, boost income and send their children to school instead of to work.

Farmers: E-FACE encourages farmers to add low-intensity crops such as apples and bamboo, which require less labor to produce more income, and rely less on children to work. MEDA is also training 250 youth aged 14-17 as agricultural sales agents. Equipped with seeds, fruit tree saplings, supplies and information, they can work in safer jobs while giving local farmers access to needed agricultural inputs.

MEDA expects E-FACE to have a direct impact on 7,000 families and more than 2,200 youths.

One of MEDA’s partners in Ethiopia is Mission for Community Development Program (MCDP), whose logo shows children carrying work implements and kicking a soccer ball. The illustration has a dual message, says Mulu Haile, executive director.

“One is that children should go for the goal,” she says. “Also, children should be playing, not working.”◆

Play is not a luxury — it’s a good way to overcome trauma and develop life skills

At play in the fi elds of the Lord

Play isn’t a strong biblical theme but you can fi nd it if you look.

David didn’t write any psalms to his favorite chariot racer. Paul didn’t write an epistle to the Troas Titans. But you can fi nd references that sound playful.

Our Maker seemed to have had a good time creating the world: “He makes the clouds his chariot, and rides on the wings of the wind” (Ps. 104:3). God created Leviathan “to sport, to frolic” in the seas (Ps. 104:26).

Even Job, not one of the Bible’s more amusing characters, depicts mountains “where all the wild beasts play” (40:20).

The perfect society — Jerusalem — is a place where one can hear “the voices of those who make merry” (Jer. 30:18-19). Zechariah 8:5 says Jerusalem “shall be full of boys and girls playing in the streets.”

It’s a safe bet God wants us to have fun, else why were we created to rather laugh than cry?

An even safer bet is that God cares about kids. For that you need look no further than Matthew 19:14 where Jesus says “let the little children come to me.” ◆

Building peace sack by sack

In fields and at looms, Ethiopians find that collaboration defuses distrust and deception

by Susan Miller

So many times we hear that we must separate business transactions from friendships and mutual care, that businesspeople have to be tough to make money in today’s world. We’re encouraged to “get ahead” more often than to “get along” or walk alongside others. When others fall behind on their mortgage payments, investors may get ahead by buying foreclosures at low prices. Farmers get higher prices on grain when others lose their crops to drought. Manufacturers may cut corners on safety concerns in order to increase profits. That’s business, right? Or is there a better way?

Trying to profit at the expense of farmers, rice millers in the Amhara region of Ethiopia over-milled the rice that farmers took to them, and sold the milling byproducts. The farmers retaliated by adding dirt to their rice to increase the weight of their grain so that they could get more money. The deception and distrust destroyed relationships as well as pride in one’s product and services, resulting in low quality and low prices for both parties. This “get what you can get away with today” business mentality kept both farmers and millers in poverty, Loren Hostetter told Kansas MEDA members and students from Hesston, Bethel and Tabor colleges — including several international students from Ethiopia — at a recent Kansas chapter meeting.

Some of the businesspeople in attendance had traveled to Ethiopia in early February to visit a MEDA project the Kansas chapter has adopted, titled Ethiopians Driving Growth through Entrepreneurship and Trade (EDGET).

Hostetter, Ethiopia’s MEDA country project manager for the past two years, described how value chain projects with both farmers and millers and with weavers and designers have proved that collaboration, rather than trying to take advantage of each other, can produce win-win business outcomes. In the case of the rice farmers and millers, the value-chain approach to business introduced by MEDA included having the millers provide transportation and storage services for the farmers’ crop and upgrading their processing equipment to better serve the farmers. Farmers learned from extension services that investing in higher quality seeds, coming to agreement with the millers on grades and standards, and learning how to do direct sales rather than selling their rice wholesale, added value to their product. The MEDA training inspired the farmers and millers to take financial risks together for the good of each one. Weavers who are poor kept their children out of school to work so their families could subsist on the income they could generate from both the adults’ and children’s labor. With no business skills and low social status, the weavers were often taken advantage of by traders. The future for the weavers’ families looked no better than the past since the input supply price increased faster than market prices. Weavers had little

Photo by Steve Sugrim

“The only way to build business is to trust,” says Loren Hostetter, shown here on the job in Ethiopia.

incentive to work every day and no way to save money to invest in new technology. Occupational health and safety conditions needed to be addressed as well.

EDGET brought the weavers together with traders and high-end designers and markets. Where previously there was conflict between the weavers and traders, relationships of trust are being built, Hostetter said. Lead weavers receive commissions on sales as they coordinate clusters of weavers and collaborate with traders and designers to meet lucrative orders. EDGET project weavers and designers are now working on a contract with Ethiopian Airlines to create traditional designs for flight attendants’ uniforms.

Weavers, although mostly illiterate, learned business skills and formed savings groups. As their weekly contributions to the group accounts build, members may borrow from them to purchase bulk supplies and equipment. “They are really excited about their new relationships,” Hostetter said. “They find that working together with trading partners is better than working against them. “The only way to build business is to trust.” By working cooperatively with high-end designers who invest in their training and provide raw materials, the weavers complete the appropriate quality work on schedule and are rewarded incentive pay for their efforts. With enhanced income, weavers can afford to keep their children in school. Buyers do their part by agreeing not to buy products made by child laborers.

In this new climate of justice and mutually beneficial relationships, farmers, weavers, millers, designers and all those who provide materials, credit and services to each other are building peace in the business world. Instead of winners and losers, everyone benefits. ◆

Susan Miller is a freelance writer who lives in Hesston, Kansas.

Why giving is so good

Being generous pays dividends ... in more ways than one

by Lance Woodbury

Philanthropy is not a word frequently used among many families with whom I interact.

Defi ned generally as “the disposition or active effort to promote the happiness and well-being of others,” philanthropy, in the last few hundred years, has taken on the meaning of generous giving to good causes. While philanthropic action certainly benefi ts the recipients of gifts, my goal in this meditation is to encourage the practice of philanthropy or generous giving as a means of enhancing and developing the family business. Here are three benefi ts for family businesses that formally embrace philanthropy in their organizations. 1. Holding the family together. As businesses in general, and agricultural businesses in particular, see fewer children return to the company, giving money away or participating in activities to help those less fortunate offers a chance for all family members to interact with one another. Participating in a charitable event or serving on a scholarship committee gives siblings and parents a chance to develop and sustain relationships in a deeper way than just spending time socially as a family. It brings purpose and a level of discipline to their interaction, and it can reveal the diverse skill-sets among family members. Philanthropic activity can cultivate an appreciation for one another in a way that social activity, or even business activity, cannot. In more than one instance, I have seen how philanthropic activity in a family business gives new direction to individual family member’s lives, igniting a passion for service and understanding that previously was absent. 2. Broadening the family legacy. Every community has business-owning families who are recognized for their success. But I know a few family businesses whose legacy is more than business success: their legacy is about the difference they make in the lives of others. It seems to me, at least anecdotally, that those difference-making organizations generate more enthusiasm and better morale among employees. They are talked of more positively in the community. They are sought out frequently for partnership opportunities, and they often contribute positively to the image of their industry. Their charitable activity doesn’t necessarily make them more or less profi table, and they often don’t seek the spotlight. However, when you look back over 50 or 100 years, it is those philanthropic families who are seen as having made the world a better place. Mike Miller, a friend who works for Mennonite Economic Development Associates, has many stories about businesses whose success in North America has been strengthened through their participation in activities to alleviate poverty in developing countries. It really works! 3. Communicating important family values. The decision to involve family members in charitable acts — the giving of money, resources, time or talents in the service of others — provides a powerful medium for communicating what the family truly values. As a trustee of the Finnup Foundation of Garden City, Kansas, I constantly have the founders’ values in mind as I make grants or interview prospective grantees. When I talk with agricultural families, I often hear them talk about how they want to perpetuate the values that have made them successful. For example, some value their management of land, which enters into their gifting of fi nancial resources as they become more successful. I know several family business owners who value a college education and thus fund scholarships for employees or community members or give directly to schools for this purpose. I’ve seen family business members who value helping those in extreme poverty and so they encourage mission trips or participation in Habitat for Humanity projects. The point is that philanthropy or generous giving can shape future generations by identifying and communicating the core principles of family business members.

Doing philanthropy well — giving money away to effect change, or using your time and energy productively to serve others — is not an easy task. The dividend, however, can be much greater than any fi nancial reward. Good family relationships, a positive infl uence on future generations, and an enduring legacy are assets that truly are a family business’s wealth. ◆

Lance Woodbury, an advisor to family-owned and closely-held businesses, will be a presenter at MEDA’s annual convention, Nov. 7-10 in Wichita, Kansas. His article is reprinted with permission from his book, The Enduring Legacy: Essential Family Business Values.

Bossy witness?

Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect.... (1 Peter 3:15-16, NIV)

Overzealous Christians who ignore Peter’s words on “gentleness and respect” have given witnessing a bad name.

Others have overreacted by muting their verbal witness entirely. Many Christians may be eager to share political opinions but take a vow of silence when it comes to sharing opinions about Jesus Christ. Perhaps it is time to remind ourselves of the old saying, “When the heart is on fi re, sparks will fl y out of the mouth.”

Ian had the problems of Job, but so far his

work hadn’t suffered. Though sometimes frazzled, he still completed his projects on time and on target. On the surface everything seemed fi ne with Doreen’s star employee.

However, it wasn’t. From a reliable source, she learned that Ian’s personal life was a mess. His fi nances were in shambles. Setbacks seemed to seek him out.

His marriage had recently failed, and the divorce was messy and expensive. Ian clung to the hope that he could at least be a good father to the teenage children. But then there were problems with drugs. Just the other day someone in the offi ce had overheard Ian utter the words “probation offi cer” on the telephone.

Ian’s life was falling apart. Now he had turned to alcohol, but only on his own time. It hadn’t affected his work. Not yet.

Doreen knew what a great healer Jesus Christ could be. She had become a Christian in her early twenties after a personal crisis pushed her to the edge of despair. At a time when she saw no possibility of love anywhere, a compassionate Christian community had wrapped her in love and given her more support and purpose than she thought possible. Armed with new direction, her life had changed dramatically.

Doreen wondered how she could share her faith with Ian without seeming pushy. After all, she was his department head. She held some of the keys to his professional future, and he knew it. She wanted to be sensitive to his needs as well as to her delicate position as his boss.

How would she come across if she became more assertive about spiritual matters? She had never had a personal relationship with Ian. She was many years his elder and had never so much as had a cup of coffee with him outside the work setting.

Wouldn’t it seem odd for her suddenly to inject

She watched her star employee struggle, and wondered when — or if — some spiritual counsel would be appropriate

spiritual direction into the relationship? Would she be overstepping her bounds?

No doubt he would be embarrassed to learn that his boss knew the extent of his personal problems. Would he feel obligated to respond affi rmatively? How she wished she had begun earlier to become closer to this hurting young man. Then she would have had a better foundation for intervening now. But she hadn’t.

Doreen’s own boss was not a Christian. Would he think it improper for her to give spiritual counsel within the company?

Doreen was convinced she had much to offer Ian. She yearned to do so. But how assertively should she share?

Further questions

1. Missionaries sometimes speak of “rice Christians” who agree to “convert” to gain material benefi t. Can people in the workplace be similarly

tempted? 2. What experience have you had in giving a forthright Christian testimony without seeming pushy or intrusive? Can witnessing on the job disrupt the workplace atmosphere? 3. If you owned the company, how would you feel about employees sharing “their gospel” with others on staff? Would it make a difference if the employees practiced some other religion? ◆

Abridged from Faith Dilemmas for Marketplace Christians by Ben Sprunger, Carol J. Suter and Wally Kroeker (Herald Press, 1997). Available for free download at www.meda.org