44 minute read

Soul enterprise

Latte for the Lord

Advertisement

Barista Paul Johnson, 30, does more than serve a morning fix. His patrons in St. Paul, Minn., also get a smile, some warm conversation and his “latte art,”which is what he calls espresso-and-milk beverages topped with an attractive pattern. He enjoys getting to know a lot of people and being able to craft something they will savor.

In an interview printed in FaithInTheWorkplace.com the lattemeister explains how his job is part of his Christian witness. “You’d be surprised how much of a relationship you can have with someone in one-minute conversations spread out over several years.... All of my co-workers know that I’m a Christian, and often I might be the only Christian that they have any kind of relationship with. I’ll freely talk about my faith if and when they want to hear, but I think that my role more frequently is one of dissolving stereotypes of what Christians are like. People see that I’m a Christian and not a hater, bigot, judging, stupid, ultraconservative, gun-toting, sheltered, jerk. Those preconceptions ... can be real barriers to those looking at Christ’s body from the outside.”

He also thinks it’s important to be good at his craft. “So often people think of the Christian version of something as synonymous with the lame version of whatever it is, whether that’s Christian pop music or burned percolated church coffee.... The gifts we have and the gifts given to us in creation (like the coffee plant for instance) most glorify God when their potential is appreciated and creatively and passionately explored.”

A tool to plant seeds

Former MEDA intern Tom Affleck (above) sent us a report on the impact of his work with MEDA and the ripple effect of serving-with-soul. He is now head of SchoolBOX, which promotes education in Nicaragua by providing education packages, building classrooms and organizing sporting events for children.

I was fortunate enough to work with MEDA for a couple of years in both Peru and Nicaragua. I am a believer in MEDA’s work.

I thought you might be interested in a MEDA success story. Ronald Chavarria Arauz worked with MEDA (particularly COFAM) in Nicaragua. When he started working for MEDA I believe he was living in a church, sleeping on the pews. MEDA staff saw promise in Ronald, however, and eventually gave him a good position and paid for a significant part of his university education.

When MEDA’s involvement in COFAM came to an end Ronald continued to run the program. He and his partner eventually were able to turn COFAM into a profitable organization. Ronald is now a silent partner but does receive an annual share of profits.

Ronald now devotes his time and energy to SchoolBOX (schoolbox.ca). We are a Canadian charity that helps to Make Education Possible. I founded SchoolBOX in 2006 and Ronald joined in 2007. We had met while I was working with MEDA on the PRODUMER project. At that time I was working with Agromonitor, the software system which we worked to develop in PERU.

While you are tallying up the successes of MEDA in Nicaragua I think that in some small way you should include SchoolBOX as one of them. I would never have been in Nicaragua if it was not for MEDA. God has wonderful ways and I am very glad that he used MEDA as a tool to plant the seeds which would later become SchoolBOX. I would like to add, Nicaragua is the country where I truly became a Christian. Steve Rannekleiv, PRODUMER’s former director, played a significant role in my coming to Christ.

Peter Dueck (left) sees a strong link between pastoring and being in business. He is co-president of Vidir Machine Inc. in Manitoba’s Interlake district. The company specializes in storage and handling solutions for big box stores (display and storage mechanisms for carpets, vinyl flooring, tires, bicycles, etc.). It sells widely to the United States, Canada, Mexico, Chile and Australia. Having earlier been a pastor of two churches in Alberta, he sees a great deal of skills transference between church ministry and business. “Seminary prepares you to be an ethical, moral businessman,” he says, “and business teaches you how to behave, act and interact with people, which you need in the church. I think that every pastor should first be in business, and every businessman should first be a pastor.”

Golden Rule prize

“How can a lawyer, businessperson, construction worker, doctor, educator, clergyperson, dog walker, police officer, traffic warden, nurse, shop assistant, caregiver, librarian, chef, cab driver, receptionist, author, secretary, cleaner, or banker observe the Golden Rule in the course of his or her work? What would be the realistic criteria of a compassionate company? If your profession made a serious attempt to become more compassionate, what impact would this have on your immediate environment and the global community? To whom in your profession and your own place of work would you give a Golden Rule prize?” — Karen Armstrong in Twelve Steps to A Compassionate Life

Overheard:

From a defense lawyer

Alicia and four other lawyers and four staff are on the edge most of the day. Each of them works hard to achieve results that are, many times, unattainable. Each client wants a miracle. Pressure is the nature of criminal defense. For Alicia, these are the times her faith steps in to dictate her day.

Alicia is proud that she never yells, rarely raises her voice, and seeks to avoid any rash behavior. For her, these traits are due solely to her faith in Christ. Recently, her assistant said, “You are my all-time favorite boss. You never yell at me when I make a mistake.”

Alicia comments: “Over the years, I have learned patience does not develop for anybody overnight. God’s continuous help is required for the development of patience.” — Member Mission Network

“The quickest way to double your money is to fold it and put it back into your pocket.” — Will Rogers

Perennial passion

A different kind of farmer, John Schroeder produces food for the soul

“The best perennials,” quips John Schroeder, “come out of the blue.” That’s a bit of an in-gag at his company, Valleybrook Gardens, whose line of herbaceous perennial plants come in little blue pots that by some miracle of branding Schroeder managed to trademark. If you buy a perennial in a blue pot at an independent Canadian garden center, it comes from Valleybrook.

There’s a hint of mischief as he tells the story. He’s a witty guy who moves easily between playful and serious — playful when he talks up his branded products like Jeepers Creepers (groundcover) and Happily Ever Appster (daylilies); more philosophical when he explores the relationship between seed and sower. He clearly enjoys his calling, feels comfortable in his own corporate skin, and holds lively views about the interaction of soil, faith and business.

Behind it all is a sharp entrepreneurial mind that has built his passion for perennials into a premier North American wholesale producer.

Based in British Columbia’s fecund Fraser Valley, Valleybrook Gardens produces 2,000 varieties of containerized perennials, herbs, creepers, groundcovers, ferns and ornamental grasses. Its main customer base is independent garden centers throughout Canada and in many U.S. states, from New England to the Pacific Northwest. It also sells to landscape contractors, municipalities and public gardens.

As with much Mennonite entrepreneurship, Schroeder’s enterprise has roots on the family farm. His father immigrated to Canada in 1949, worked hard to pay off his travel debt, and in the mid-1950s bought land in the Fraser Valley. John grew up on a mixed farm with cows, pigs and chickens, and learned his work ethic by picking raspberries, gathering eggs and pulling weeds.

With a start like that, further agriculture studies was not a big leap. It was at University of British Columbia where his entrepreneurial instincts flourished in the late 1970s.

“In summertime I was lucky enough to get a job with the provincial department of agriculture extension office, where I saw a lot of different facets of agriculture,” he says. “One of the things I learned is that the horticultural industry (ornamentals) had a couple of characteristics that really made it very attractive from a business perspective. One, it is a high-value crop, “I love to see so you could make a living on five acres which is the land I opportunity, had available to rent from my father. Two, it wasn’t a very get something well organized industry from a market point of view. I noticed started, get in too many points on the distribution channel. There was a grower and a final customer there and be but there were a lot of brokers and middlemen in between. hands-on.” It seemed to me there was opportunity to cut out a lot of the intermediate steps and develop a business. And that’s what got me started.

“So in my third year at university I majored in the ornamental industry. One class had a propagation assignment — we had to put roots on something. I ended up getting some cuttings of heather, an ornamental plant, and ran my experiment in the university greenhouse. I took home a few thousand cuttings and together with a partner put some roots on them in a little greenhouse we built in the back yard. I put them into pots and we successfully grew them to maturity. Then we sold them, and I was absolutely hooked. Because all you had to do was take an existing plant, and there were plenty of them growing locally, snip off a little piece for no cost, stick it into a little bit of soil, grow roots, pay a nickel for a pot and some soil, and six months later you could sell it for 60 or 70 cents, multiple times the direct costs. It seemed to me this was an easy way to get rich quick. That sucked me in.”

He chuckles with seasoned hindsight. As he knows now, “it’s not easy to get rich, and it certainly isn’t quick. But it has turned out to be a good industry to be in.”

Total staff swings from 40 in the lowest off-season to 250 at peak times. John Schroeder: A feeling of awe as life emerges anew.

After graduating in 1980 he and his wife Kelly

set out to build the business in Abbotsford, B.C. He had five acres he rented from his father, and bought five more.

Perennials were catching on, and Schroeder caught the wave. Back then, a plant was just something in a black pot with basic labelling; its origin was a mystery. Schroeder saw early that branding and differentiating his product would be important.

“Because we focused on marketing we were able to establish a significant position in the marketplace. We really worked at de-commodifying our product and creating some pull and demand from the consumer. And we developed good logistics capabilities, which is why we are able to ship product on short notice throughout Canada and much of the U.S.”

Today he has 25 acres in British Columbia, where he has captured a quarter of the independent garden center market. He has another 30 acres near Niagara-on-the-

Machines plunge fresh rootlets, six at a time, into tiny pots of soil.

Lake, Ontario. Each location serves 300-400 customers. He also sells successfully into the U.S., though the market there is more competitive with slimmer margins, lower prices and an exchange rate roller-coaster.

In recent years Valleybrook has begun selling to mass markets. In 2002 it added Costco and in 2008 the large Canadian Loblaws chain (President’s Choice label). Big box stores get mixed reviews but Schroeder’s experience has been positive. “These two seem to have the best philosophy of working with their vendors,” he says. “They have loyalty, they do not beat you down on price, they value quality and they value a good relationship with suppliers. That’s the only reason I’ve wanted to deal with someone of that size.” We stroll through his B.C. operation in late spring, the busiest season. He chats comfortably with staff, who are largely Indo-Canadian, and jokes with them as they stack trays or operate machines that plunge fresh rootlets, six at a time, into tiny plastic pots.

Schroeder’s total staff component swings from 40 at the lowest off-season point to 250 at peak times. “Fifty percent of our sales for the year occur in five weeks — between the middle of April and the end of May. We’re potting like crazy right now,” he says.

In university he took some cuttings, put roots on them, stuck them into pots and grew them to maturity. “I was absolutely hooked.”

Guru to gardeners

The reach of the Internet has been artfully employed by the folks at Valleybrook Gardens (www.valleybrook.com). People who want to green their thumbs can join 14,000 regular visitors to the company’s New Perennial Club (www.perennials.com) to access design tips, resources and expert advice. Among the typical questions: “What can I grow in the shade?” or “Why is my hibiscus not growing?”

Then there’s this one: “What in the world is Bloody Dock?” (It’s a relative of garden spinach and rhubarb, lest you thought it was a British expletive.) ◆

He reduced the Surrounded as he is by thousands of plants, the points on the question comes up — what are his own favorites? “That’s distribution easy,” he laughs. “My personal favorites are the plants channel, then that I’ve got and nobody else does, that are easy to grow and I can sell for lots of profit. focused on I’m a very shallow individual, obviously.” branding and More seriously, the plant market can be like fashions differentiating — in today, out tomorrow, he says. Some years junipers his product. are in, and people plant lots of them. “For years we had a plant called black snake root. We were the only ones that carried it, and it sold really well. Very attractive, great plant for a decade.” Schroeder now faces the inevitable what-next question of succession planning and exit strategy. “I’m 54, been doing it for 31 years,” he says. “My exit strategy always has been to build a business that was attractive and salable.

“I love to see opportunity, get something started, get in there and be hands-on. At this point I’ve become more of an overseer, a manager. My goal was to create a market-leading nursery and I feel that I’ve accomplished that. I don’t have any future big goals to take this further. There are other things I’d like to do.”

Shifting career gears could also allow other interests to, well, blossom. An avid photographer, his library contains 30,000 photos, many of them, not surprisingly, of plants. He also loves to travel, which he describes as “one of my greatest sources of joy.” Every second year he puts together a horticultural tour designed for business owners in his industry. The last one was to Japan; the next is to India this fall.

Could other plant-related ventures beckon? Schroeder says he and Kelly might consider relocating to BC’s Okanagan Valley, Canada’s version of a desert. It’s a very dry area where water is a growing concern.

“I’d like to develop a business that grows droughttolerant plants, particularly cactus. I’d like to be the cactus king of Canada,” he says, grinning. “More seriously, it’s amazing how many cacti are hardy in Canada. All provinces from British Columbia to Ontario have species of native cactus and many more are hardy here. You can create wonderful gardens that survive the cold climate and have fabulous flowers. Who knew?”

Schroeder remembers a wall plaque with

a quote from Dorothy Frances Gurney — “One is nearer God’s heart in a garden than anywhere else on earth.”

While he’s cautious to not romanticize entrepreneurship, he does appreciate the spiritual connections of his work. “It’s almost like a creation kind of a thing,” he says, “because you’re taking something that doesn’t exist and you’re making anew, whether it’s a seed or taking a cutting or even building a garden. I think it’s very appropriate that the Bible starts in a garden and ends with a garden, with the trees beside the river of life.

“I think I’m in the best kind of business you can be in.” ◆

Food for the soul

“I really do like plants,” says John Schroeder. “Right from a child one of the things I remember is that feeling of awe and joy in the spring when all the plants that had disappeared the year before would start pushing their way out of the ground and you’d see the little tiger lilies and trilliums come up. That remains a source of joy and a wonderful reminder of resurrection and new life. It’s very appropriate that Easter comes at our busiest time of the year.

“Somebody once asked me why I considered this to be farming, since we’re not producing food. I said No, we’re not producing food to eat, but flowers are food for the soul. The world we live in was created to be enjoyed because there is a lot of stuff in it that is there for no other reason than to look beautiful. ◆That’s something I really enjoy, to be a part of that.”

Retired? Yeah, right.

Spunk and a well-tailored assignment gave second life to a career in banking

She calls herself “just an old banker,” but Ruth Jacobs has plenty of tread left on the tires, and she’s using it to gain traction for the poor in developing countries.

At a stage in life when many folk would contemplate leisure, Jacobs joined MEDA’s financial services team and went out on a worldwide journey to promote “mobilization of deposits” among people who may never before have walked into a bank.

Deposit mobilization, also called financial inclusion, is the latest rung on the ladder of financial services for the poor, two billion of whom are “unbanked.” A simple thing like savings, which North Americans take for granted, remains out of reach for many in the developing world. Jacobs and her MEDA team are out to change that.

No matter how poor clients may be, they still want some of the same basic financial services enjoyed by more affluent westerners, Jacobs points out. “They all want the same thing. They want respect; they want a safe place to put their money; they want knowledgeable people to serve them, and they want to know they can get their money when they need it.

“That may seem pretty straightforward, but in some developing countries it’s not the norm, especially for women. They are pushed aside; bankers ignore them. Yet access to savings and services empowers them to maximize economic opportunities, invest in their families and become an economic benefit to their communities. This is the way they can build the next generation of financially literate customers.”

While microcredit has

gotten plenty of attention, the behind-the-scenes issues of deposit readiness and regulation aren’t headline-grabbers. MEDA was a pioneer in the microcredit industry but strategically went deeper and has worked at these issues for some time in places like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tajikistan and the Philippines.

MEDA’s contribution has been on the formal side, including introducing savings products to newly-regulated microfinance institutions (MFIs) and helping existing banks position themselves to serve this previously ignored sector.

Jacobs’ excitement builds as she describes the opportunities to make a difference in the lives of the poor, especially with advances in technology. “Just think — in the U.S., automatic teller machines took 20 years to gain acceptance; mobile banking took seven years. Internet banking took only six months to catch on. This is a great time to be out there with savings.”

How she came to MEDA involves a circuitous route where her considerable talents emerged layer by layer.

A former school and music teacher, she was giving private piano lessons to the president of a New Hampshire bank back in 1980. “We’d done middle C I don’t know how many times. One day I blurted out, ‘Why don’t you give me a job.’ And he did!”

She started out in customer service, and three weeks later became a teller. When the bank needed new software systems Jacobs was given a coding sheet to put into the system. “I’m thinking, what the heck do I do with this? But I figured it out,” she recalls. Her instinctive aptitude shone through and she was sent to programming school. She became a computer programmer in charge of converting manual systems to in-house automated systems, and then was put in charge of coordinating training and writing manuals. She spent 26 years as a banker, ending up as chief operations officer. She heard about MEDA from her friend Joyce Lehman, who at the time operated her own accounting firm in Keene, N.H., and served on the MEDA board. Lehman eventually jumped from the board to staff, and worked extensively in MEDA’s financial services program in Afghanistan before joining the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Ruth Jacobs: “We raise up the hood, look at the engine, and try to fix it.”

“Joyce would talk to me about her move through the MEDA learning curve and every so often would say to me, ‘You ought to be doing this too’.”

In 2004 that suggestion became a formal invitation.

“One day Joyce mentioned that MEDA really needed help in Afghanistan. And out of my mouth came the words, ‘Oh, okay.’ I went home and told my husband, ‘Joyce has asked me to go to Afghanistan’.”

Now she had to clear it with her bank. “I told the board I really wanted to do this, and they gave me permission to go for a few weeks.”

It was Jacobs’ first real experience with traveling. She’d never even been to Europe, and now she was going to Kabul to help document processes at MEDA’s partner agency, Women for Women International.

Her skills were precisely what was needed. No sooner had she returned to her bank after the short assignment when she got a call from Julie Redfern, MEDA’s vicepresident of financial “I went home and services, asking her to go back to Afghanistan for told my husband, several months to fill a spot at the same partner ‘Joyce has asked agency. Jacobs retired from me to go to the bank at the end of 2005 and within weeks was on her way back to Afghanistan’.” Kabul. Task completed, she went on to Lahore, Pakistan, to work with another MEDA partner, and began working in deposit mobilization. Her assignment kept evolving with MEDA’s deepening involvement in financial services. Now she is MEDA’s in-house expert on deposit mobilization and risk-management methodology, though she describes it more simply as a mechanic tending to a broken-down car. “We raise up the hood, look at the engine, and try to fix it,” she says.

Jacobs works with financial institutions who

want to change who they are in order to expand their services to a segment of society they haven’t worked with before. This includes working with the human capacity and infrastructure, doing a lot of mentoring and coaching. “I try to help them to be a bank,” she explains. “How do you keep your customers in focus and how do you not lose your mission? I lay out for them what they need to be a real bank, to comply with regulations.”

Regulatory transformation can be a bugaboo to a fledgling institution, she says. “How do you work with regulators, who expect certain areas of compliance in internal controls and corporate governance? Any institution that wants to transform needs to know what this means. Also, when you become a regulated institution, your board requirements change, and how do you navigate this shift. We also look at risk-management: what are the risks of putting a product out there, and how do you manage it.”

Existing banks need help, too. Many of them made the poor feel unwelcome, if not by direct exclusion at least by lack of services that they needed. And many have seen the error of their ways, recognizing that there’s a big untapped market they hadn’t seen before.

Jacobs gets great satisfaction seeing the practical impact in the teller lines. “People are opening up new deposit and loan accounts,” she says. “They’re actually going into banks where they’ve never been allowed in before.”

Her work demands understanding from her family, as she can be gone for months at a time with only the odd week back home in Keene, N.H. “My husband Carl — he’s pretty cool — has been very supportive,” she says. “My son and daughter especially love what I’m doing, as does my mother, who is 90.”

What do her old banking friends think about her reinvented career? “First of all they think I’m crazy,” she laughs. “But they’re very interested in the level of regulatory involvement. I tell them that all of the same issues we faced 15-20 years ago in the bank are now coming across the ocean to developing countries. The things I implemented back then are now being done overseas for the first or second time. I’m hoping that all the lessons I learned back at the bank will make a difference in how I approach it there.”

Jacobs also loves meeting people. “There was nothing more exhilarating than sitting out on the mud floor outside of Kabul with the women and watching the children peek out, sort of look at me like, What is this? And the communication — how do we communicate? Fun for me, too, is walking in some of the dust and earth that is so ancient, and realizing that I’m walking in the footsteps of ancient wisdom. It’s not only fun, it’s incredibly humbling, it’s been there so long.”

She also delights in seeing transformation take place as women move out of their cultural straight-jackets and become economically empowered and confident. Like when she introduced a banking concept that everyone said was too difficult for this sector to grasp. “Suddenly someone said, ‘Wow, this is great.’ And you instantly realize you’ve crossed over and given them a tool. Everyone said it was going to be too complicated. No it’s not. They’re capable of this.”

Jacobs sees it in other small gestures that are freighted with local significance. “The women will shake a hand with a man, something they wouldn’t do before,” she says. “They’ll ride in a car in Kabul, they’ll speak to a man.”

She also sees ventilation among males. “When I left Pakistan,” she says, “two young men we worked with gave me a big hug, which doesn’t happen in that culture. They called me Mom!”◆

Dear children...

Leaving a legacy beyond money

What do you plan to leave your heirs?

Myrl Nofziger wants it to be more than money.

Most people have a Will which disposes of their earthly treasures, he says. But how about also writing a “testament” that spells out hopes and expectations for the next generations. “That document may be even more important than our Will,” he says.

Nofziger and his wife Phyllis live In Goshen, Indiana, where he has spent 43 years as a developer of residential, commercial and industrial real estate. They have sought to practice generosity, both with money and talents. “We are here on earth to faithfully maximize the gifts God has given us,” says Nofziger.

Diligent work and stewardship were modeled by his parents as he was growing up on a farm near Archbold, Ohio. From early on he drove tractor, fed chickens, caught geese by hand for slaughter, and cleaned out barn manure.

He grew up in a home where support for the church was paramount. “My parents always practiced tithing-plus,” he says. “Missions was always a part of their vocabulary. If a missionary returned from a foreign assignment we went to hear them speak. So mission work just plain got into my blood.

“I have always spent one third of my work week in charitable or community activities. This I learned from my father.”

Myrl and Phyllis have been active in mission work in Zimbabwe. Myrl has worked with Rotary polio eradication programs in India and Nigeria, and serves on the board of LCC International University in Lithuania.

“For us, philanthropy is a major part of our everyday lives,” he says. “Whether it is a Rotary grant for school equipment in an orphanage in Zimbabwe, or giving polio drops in a foreign country, it is a passion.”

They hope their values and passion will also get into the blood of their children and six grandchildren. To this end, he has written them a “post-mortem” letter (condensed version shown on facing page), which he amends periodically.

“We all want to pass on to our families a wholesome lifestyle and a Christian worldview,” he says. “Though we cannot force it upon our children, we can aspire to be good role models and pass on Godly wisdom.” ◆

Myrl Nofziger: “Mission work just plain got into my blood.”

Nofziger administering polio drops in Africa.

Dear children and grandchildren,I have enjoyed very much being a part of your childhood years, as well as those years where you have moved into adulthood and beyond. I know that Ardith [wife of 25 years, deceased] and Phyllis have taken the responsibility of many of the domestic and parenting responsibilities, due to my professional responsibilities and travel schedules. I feel indebted to them both, in many ways. They have always been available and have done a great job! A parent’s greatest wish is to see their children grow up within the framework of a Christian (Anabaptist) environment and to be able to pass that lifestyle and theology on to their children. We would hope that faith in Christ is of major importance to you and thereby that you would live a life free of sexual immorality, drinking to excess, use of tobacco and drugs. It is important that you think “globally” and not just locally or about yourself. Issues such as immigration, persons of different ethnic backgrounds, how you treat the poor, people who are or have been incarcerated, war – the list goes on and will change from time to time. In my Will there are stipulations that money be given at certain times to each of you only if you have been faithful to a holistic lifestyle. We know that we cannot force a certain lifestyle on you; we only hope that we have been good role models for you.As you all know, tithing and charitable giving have been a major part of our lives. Please make it a part of your lives, do not wait. We have tried to give above and beyond what is considered a tithe throughout our lives. In our estate planning a major part of our estate will eventually end up with charity. This pertains to either the asset base or the income derived from it. We feel that helping to provide you a college education has been a major asset for you and our greatest gift to you, in preparing you for life’s challenges and opportunities. In the meantime we have done extensive estate planning and relocating of assets to maximize the benefits to you, as well as to charity, and to minimize the various tax consequences.Each of you has talents. It is up to you where and how you want to spend them. As you gain in knowledge, maturity, wisdom and finances (save a % out of all income you receive), your accountability increases. It is not our responsibility to choose your life’s partner and/or your vocation in life. It is only our responsibility to provide you an atmosphere where you can make intelligent decisions. We hope and pray that we have done that. We do encourage you to become involved in church, community and arts-related activities. Please give freely in those areas. The more you give the more you receive. The more you help someone else achieve their goals the sooner you will achieve your goals. Always, always maximize your efforts and potential. Be the best. Henry Ford once said, “One who fears the future, who fears failure, limits his activities.”If and when you have children, provide them a religious-based home and encourage education to your maximum capabilities. Set guidelines for them in their entertainment (movies, sports, TV watching, etc.) and lifestyle expectations. Involve them in household responsibilities. Be frugal in money expenditures and gifts to your children. Teach them time management. Time is your most precious asset, do not waste it. It is important in your discussions with your children that you also practice what you preach. (Actions speak louder than words.) Provide for many family activities and vacations together. Be available to your children. A family that prays and plays together stays together. Please forgive us where we have failed in being good examples. We still had/have much to learn in our faith journey. There is no greater gift than “servant leadership” to others. In summary, life is like a ball game. Establish a goal and head for it. Many people do not know where the goal is and often fall short of it, or cross it and do not even know it. We know that Christ died for our sins and that he loves us. Pray daily and ask God for forgiveness. Life is a pilgrimage. The minute we are born we start to die. Be of good cheer and do well! Our testament and legacy Love, Dad

Man of steel

He’s young, devout and brimming with joy

Earl Pauls is one happy guy.

Perpetually cheerful, energized by his work, he seems to bounce along on some inner trampoline.

Why is he so happy?

For starters, he dotes on his faith, and of course his family, which includes wife Jenilee and two preschoolers (James and Aaron) with a third on the way.

Then, too, he loves his work as a welder and steel fabricator. He owns and operates EP Industries Ltd. in Chilliwack, British Columbia, a company he founded while still in his teens.

You can feel his effervescence above the din and sparks in his shop. Welders in Darth Vadar-like masks hunch over their work as music blares above the sizzle and steel. The music — today, aptly, it’s heavy metal — may not be his choice, but he gives in once in a while. It’s what they like and Pauls won’t stand in their way. He wants them to enjoy their work.

Pauls, now 30, got his

first taste of welding on his family’s chicken farm. “My Dad had an old welder in his shop that I liked to play with,” he recalls.

After high school he worked in a cabinet shop but when he realized that the top guy was earning $18 an hour he decided he would aim higher. He had always been interested in owning his own business; why not with welding?

Pauls began making heavy duty mailboxes. When his father needed a new bucket for his Bobcat, he let Earl try his hand.

“I just loved it,” Pauls says. “I thought it was the coolest thing ever.”

He kept refining his skills and worked his way up to Canadian Welding Bureau certification which allows him to do structural welding.

“A friend needed some tractor trailers and asked me if I could make them,” he says. “‘How many?’ I asked. ‘Seven,’ he said. I was ecstatic. Here I was making hun-

dred-dollar mailboxes and now I had a chance for a larger project. I started building them and absolutely loved every second of it.” Someone from the Rotary Club saw his work and wanted a train for a parade. So Pauls made a train. “It kept going and going by word of mouth, and it never stopped,” he says. “Soon there was an entire machine shed on my father’s farm filled with my equipment.” He moved to his own location and widened his product line to include metal bridge work and various kinds of metal brackets and steel frames for industrial applications.

Only 30, and with 12 years under his belt, Earl Pauls still loves his work.

For the last three years his market niche has been manufacturing modular building skids that the booming Alberta oil industry uses as a base for mobile houses and kitchens. The skids amount to three long parallel I beams, 55-65 feet long and eight feet wide, with pipe spreaders in between. Pauls devised the manufacturing process himself, visualizing it in his mind, then used a computer to come up with the precise measurements. “Over a period of six months I kept contemplating better and better ways to do it,” he says. “Then I set up an assembly line with jigs and structures to hold the steel in place for greater efficiency

so I could actually gain a competitive edge. To the average guy looking at it there’s not a lot of money in it.”

Output averages three skids a day, and the market looks robust. The more drilling sites come into play, the greater demand for modular skids. “I try not to smile too much when the price of oil goes up,” says Pauls, who deals with most of the major players in modular building in western Canada.

With a laugh he describes his company’s modest involvement in the 2010 Winter Olympic Games in Whistler, B.C. His skids were used as a base for the Games’ anti-doping units. Washrooms with mirrors on three sides were built for athletes to provide their test samples under supervision.

Pauls also makes bridge rails and posts, general structural steel, and some farm equipment. He takes pride in quality, precision and “on time, every time.”

The love of welding and fabrication has not dimin-

Earl’s ode to joy

While he’s more at home in the welding shop, Earl Pauls sometimes lets his effervescence flow out in print, as shown in the following testimony:

Joy. I have so much of it, and I draw it out of so many things and see it in so many places.

Some people see only the mundane: get home from work, help with the little ones, clean up, get ready to go somewhere, and on and on it goes. I thank God for a way to support my family.

After a long day’s work, I am thankful for how much I love my job and the challenges of running a business. I am thankful for a wife who has a hot dinner waiting for me. I am thankful for the privilege of entering my home, my castle, and having our eldest son run to me with perfect trust that I will fling him up into the air, catch him, hold him and tell him I love him. Fetch something from the freezer for my wife or send her on her way with some friends to get out of the house for a change. It gives me pleasure just to change a diaper and know that I can do that to make a difference, clean a runny nose or wash dirty hands. Help my father with something he is working on. It is not just another thing I need to do to get through the day, but an opportunity — a joy — to love and spend time shouting my joy for the people so dear to me.

We live in Canada! Yes the taxes can get high, there is crazy government spending, so many decisions — I know I could do better. We can sit around and whine, maybe even protest, but at the end of the day, we live! Really live. Live in the country, live in the city, live anywhere. Do what we want, go where we please. The ished in the dozen years he’s been in business. “I still love driving the fork lift, moving big chunks of steel,” he says. “I feel like I’ve been blessed.”

One wonders, does a happy guy like Pauls ever have a bad day?

“It takes a lot,” says wife Jenilee, who runs her own craft supplies company from the Pauls home.

If pressed, Pauls admits to having a bad day now and then, like when employees get sick or equipment breaks down.

He credits much of his sunny outlook to spending time with God before the workday begins. Most mornings begin with half an hour of devotional time, reading the Bible and praying.

“I praise God. I pray for other people, and pray for safety for the guys as they operate their equipment,” he says.

“Most days that go south, it’s because I haven’t had devotions.” ◆

freedom that we have! We can get up every day, watch the sunrise, hear the birds’ choir and just worship Jesus. He had joy. If I think I have joy buckling in a two-year-old boy on our way to the park or helping a friend dig a trench, just think of the joy Jesus had when he said, “take up your mat and walk,” “you are

healed,” “you are forgiven.”

We don’t have to have friends, we get to! We don’t have to get married and work through it, we get to! We don’t have to help out a friend who has experienced loss, we get to! Life and family and work have joys we never dreamed of. Sometimes we just need to recognize the ones we have and enjoy the sweetness of giving and receiving.

I don’t get joy out of everything. I can’t really say I feel excited to take a shift with a teething baby at 2 a.m. I don’t really like taking out the garbage. I can get mad when things don’t go the way I expect them to on the job or when I find out after completing a job that my bid was too low and I didn’t make any money. It is disappointing when employees don’t show up or follow through. But still every night when I pray to God I thank Him for this day. Because I know that He made it and it gave Him joy to give it to me. ◆

A shattering crash on a dark highway, two lives lost, and an awe-inspiring journey of reconciliation

Security experts say the most dangerous thing most development workers will do is get behind the wheel of a car.

Loren Hostetter, MEDA’s Ethiopia project manager, discovered this firsthand when he was involved in a highway accident that claimed two lives. While he miraculously suffered only minor injuries, he has endured the greater pain of being complicit in a tragic loss of life. But he has also experienced a remarkable journey of grace and reconciliation with the families of the deceased.

Hostetter joined MEDA last fall to manage its new rice and textile project in Ethiopia. Early on May 5 he was driving back from the town of Hawassa to his home in Addis Ababa. The road was good and he was driving within the posted speed limit. He passed a taxi van which left its headlights beamed bright, briefly obscuring his vision. His car struck a donkey cart in the middle of the dark road (with no lights or reflectors), flipped and landed 50 metres beyond the impact.

Though his vehicle was destroyed, air bags kept his injuries to a minimum. But two young men on the cart were killed.

The North American practice is to stop, but in many developing countries that can be hazardous. The recommended security protocol is to head for the closest police station, as vigilante justice can often result in death to someone seen as the perpetrator.

When Hostetter crawled out of his wrecked

Loren Hostetter and Mulenesh, widow of one of the deceased.

vehicle he could not locate his cell phone. A significant number of agitated people had gathered. He retreated from the scene and caught a ride with a passing truck headed for Addis Ababa. The passengers offered him a phone to contact the U.S. Embassy, which instructed him to go to the nearest police station and wait for assistance.

Police stations in the first several towns they reached were poorly staffed and didn’t want to get involved. Finally a police station was found that would handle it. Embassy staff met Hostetter there by midmorning and advised he return to Addis. Hostetter went to his home to dress his minor wounds and then proceeded to authorities to file a complete report, which was relayed to the regional police station near the accident scene. Efforts began immediately to contact the victims’ families and arrange reparations. The community had an accepted dispute settlement mechanism with three steps: (1) meet with the community and pay immediate costs; (2) meet with elders and discuss damages, negotiated at the community level; (3) return to the community later for a reconciliation meal and ceremony. Arrangements were made to reimburse the immediate physical expenses, including replacing the donkey, cart and its ruined cargo, as well as funeral expenses. Meeting with the families went as well

as could be expected, under the tragic circumstances. The family members were Christians, and were pleased to learn that Hostetter also is a Christian.

Local elders arranged the final reconciliation phase for May 21, two weeks after the accident. The traditional ceremony includes rituals of release of wrong, giving gifts, paying respect, bonding of the two sides, and a communal meal.

Hostetter was accompanied

to that event by fellow staff and church members. “There were about 100 people huddled in the mourning tent,” he says. “Fifteen of them were from my representative group. The impression on the village when our delegation entered the tent, when they saw the genuine bond of support and sincerity of my delegation, made a great impact…they swelled with appreciation the moment we entered the mourning tent.

“After seating, there began a ritual of two elders calling and answering each other as to why this man was coming and what happened. One would call out, ‘has this man come before?’ and the other would answer, ‘no, but he sent a delegation with gifts and expressed his desire

The presentation of gifts to each bereaved family was followed by a communal blessing and a blanket ceremony, symbolizing a family bond. Shown here, Hostetter blanketed with widow Mulenesh and her children.

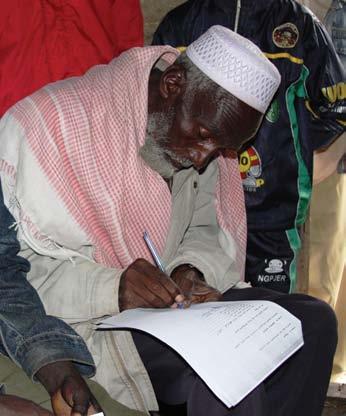

to come.’ ‘Why has he come now?’ and the other elder would answer, ‘to make peace and pay respect to the families.’ ‘Did this man commit a crime?’ ‘No, there was an accident and he intended no harm.’ So this went ... a way of recounting for all witnesses. “Then it was my turn to make a statement, and to present personal gifts of clothes and practical items and decorative items to the families. I explained that I also had a large community gathering at my home in Virginia offering prayers for these families, and that the two communities also now share a bond. On behalf of the families, the elders pronounced the gifts accepted and I was invited to sit on the mat where the families were, and they extended a hand to me to sit with them for a photo. Then large loaves of bread were broken and large chunks passed around and eaten by everyone in the tent. Large carafes of coffee were poured and passed out ceremoniously.” The village elders and the elders Hostetter brought with him had previously decided that the proper compensation would be a heifer and bull calf for each family. Hostetter and his associates could not on short notice find heifers and bull calves of suitable quality, so they proposed giving double the money for the families to buy the animals according to their choice. “We also wanted to give an animal according to their tradition, so we offered to buy in addition, a sheep for each family,” he says. An elder signs the final settlement document, also signed “This really moved the elders, and they teared up. by each of the two families. They embraced me, and told me that I had honored their

village and their culture by trying to buy calves according to their tradition, and had shown wisdom by providing amply for the family to choose their own.”

The reconciliation ceremony began with a

traditional meal out under the trees. “Then the elders and the leader called all to gather, and several speeches were made. The leader again read an account of all that I had done to show care and compensation to the families in the previous settlements and gifts. He then read the pronouncement of what the elders determined as appropriate payment and what I had offered as an alternative.”

Hostetter then presented his payments to each family. After the gifts, there was a communal blessing and a blanket ceremony, symbolizing a family bond. “The leader stated that this had been an accident, that I had compensated beyond expectations, that my sorrow was sincere, and that I honored and respected their culture. He declared that our families were now joined, and that I blessed them. The elder then asked the gathered community if they now wished to bless, to which they all raised and waved their outstretched hands toward me and uttered blessings of

They embraced him, and said he

had honored them touching, beyond any by trying to buy of our expectations. The depth of reconciliation was beyond anything calves according experienced by the seasoned Ethiopian to their tradition. leaders who went with me. I was amazed at the resiliency of the families and their outpouring of grace and gratitude.”

While this traditional ceremony provides opportunity to reconcile, it doesn’t necessarily work toward true reconciliation, Hostetter says. “These two families clearly chose to forgive and reconcile. Both families also rejected a number of blood and sacrifice rituals that are required by the orthodox church, stating ‘we are believers and we are free to forgive’.”

The village leader pronounces the settlement is complete.

peace in unison. We then obtained a written settlement, signed by each of the two families and elders.

“After the ceremony the families and elders thanked me numerous times for honoring them and paying for their losses beyond their expectation. Everyone told us that so many deaths occur on that road, but very few come back, fewer still to pay respect and compensate for the losses.”

Hostetter describes the event as “memorable and According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Ethiopia has the world’s highest rate of traffic fatalities. Donkey carts are especially vulnerable, as many travel at night without lights or reflectors and often are not seen by car and truck drivers until it’s too late. “The community elders were very cooperative and understood the situation,” says Yabetse Assefa, a member of MEDA’s Ethiopia staff who attended the ceremony. “They told us that the place where the accident had occurred is very risky and had repeated accident histories even this year. They told us that 15 people had died in one accident.” The project Hostetter is leading is to increase incomes for 10,000 smallholder rice farmers and small-scale textile artisans by helping them improve quality and integrate into higher-value markets. He has extensive international experience in agricultural value chains and agri-business development including work in South America, Eastern Europe and Africa. While working in Romania he owned and managed a start-up produce company; growing, packing and supplying fresh and frozen vegetables to supermarkets, restaurants and open air markets. While there he also joined a MEDA and World Vision micro-lending program (CAPA) to help agricultural clients gain access to credit. ◆ eviews