41 minute read

MEDA’s AGM got a vivid picture of the power of leveraging. Last year the organization worked with 233 partners in 52 countries to help 36 million families achieve healthier livelihoods.

Advertisement

Photo by Robert Hoetink

When he ran a tree and shrub business in Edmonton, Alberta, Bill Bock made regular visits to the Bissell Centre employment office to hire casual help. Now, at 87, he still visits, but for a different reason. He goes as a volunteer, helping laborers (two or three a day) connect with employers. He then drives them to their work site or gets the employer to pay for a taxi.

Bock started this informal mission after his wife died a decade ago, and he needed something to do. He talked to the folks at Bissell about matching people there with companies. He’s been at it ever since.

As he wanders around the premises wearing a trademark black cap with a red maple leaf, workers approach him for help. Many have skills in drywall, carpentry, painting and plumbing. They want to work, “and they want to work badly,” Bock says. Being jobless adds to all the other Business autopsiesproblems of poverty, says Bock, who grew up during the Depression and recalls his “What if you and I had all our business affairs opened and examfamily struggling to afford food. “They’re ined at death and reported in the daily newspaper? What if all the depressed because they think they’re worth- readers could see our income statements, our balance sheets, our less. The first thing I do is try to make them corporate minutes? How would our Christian faithfulness be diagfeel they have something to offer. That they nosed? are not throwaways.” “Would such business autopsies reveal to our fellow church

As an individual volunteer, Bock says members that we died in good spiritual health? That we tried to he can help people more readily than formal carry out our Christian responsibilities?programs slowed by “Would the autopsies show that we paid adequate bureaucracy. “If you wages and benefits? That we charged fair prices? That can do something our business practices were in harmony with what we independently of the said we believed? That we handled conflict with love and system, and assist the compassion? That we gave generously?system, it’s worth- “I don’t care if they open my body to discover the while.” cause of death. But what would my brothers and sisters

He believes his discover if they could see the inside of my business?” —work makes a dif- John H. Rudy in Moneywise Meditations: To Be Found ference. “You take a Faithful in God’s Audit personal interest in a person that is despondent, and you can save a life,” he says. Overheard: “One day your life will flash before your eyes. — Edmonton Journal Make sure it’s worth watching.” — Anonymous

MEDA convention: A visit to the colonial heartland

Making strides to grow business, and build community

Imagine this comment from a tourist: “It’s amazing how they fought all those civil war battles in parks.”

Or, “How did they fight the battle of Gettysburg with all those statues in the way?”

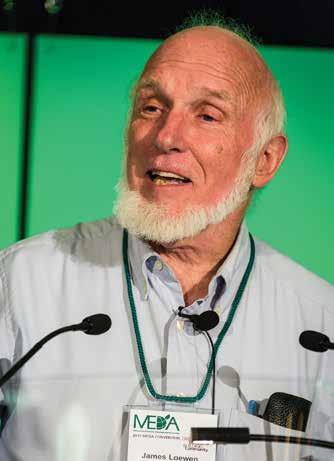

Those odd comments result from being taught “bad history,” sociologist James Loewen told the opening session of the annual MEDA convention, Nov. 5-8 in Richmond, Virginia.

In a lively humor-laced presentation Loewen addressed the issue of how America’s historical selfimage is skewed in many respects, especially as regards racism.

“We teach history worse than we teach any other topic,” he said, adding that a result of being “told lies about ourselves” is that it “makes us all stupid.”

Loewen, who holds a PhD in sociology from Harvard University, taught race relations for 20 years at the University of Vermont. He has distinguished himself as an authority on racism in America and has been an expert witness in more than 50 civil rights, voting rights and employment cases. His writings include the bestseller Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your High School History Textbook Got Wrong and Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. His presentation was well-received not only for its content but also for his magnetic humor.

The convention theme was “Growing Business, Building Community.” Its location in Richmond, Virginia, the cradle of colonialism, made it a fitting place to explore a

topic that has been much in the public consciousness — racial harmony (or lack thereof). It had poignant implications for businessfolk concerned about being moral leaders in their communities. Being taught “bad history” minimized the role of African Americans, valorized the Confederate cause, made affirmative action look silly and alienated people Steve Sugrim photo of color, said Loewen as he traced racism from the colonial period to the present. African Americans continued to lag behind in numerous categories, including marital status and income. The average African American family was 10 percent less affluent than whites. One area they led, rather than lagged, was crime. They also were readily typecast by the dominant population. “We all think categorically about black folk but we never think categorically about white folk,” he said. In his Friday seminar Loewen expanded on “sundown towns,” which he described as “all white, on purpose.” Such towns forbade blacks from staying past sundown. “I learned from my own

Diversity makes us all smarter, said Thursday keynote relatives that Mennonites speaker James Loewen, an authority on racism. could be as racist as any-

body else,” said Loewen, who has ancestral Mennonite roots in Mountain Lake, Minn. According to his research, a number of predominantly Mennonite communities (Goshen, Ind., Bluffton, Ohio, and Hillsboro, Kan.) were sundown towns.

Such towns were, surprisingly, a northern phenomenon, Loewen said. “They are all over the place except in the deep south. The state of Illinois alone had 507 sundown towns. In fact, 70 percent of all the towns in Illinois were sundown towns. It’s not a southern phenomenon.”

He said his goal was to document every sundown town in the U.S. “Getting people to acknowledge their past is the first step to transformation,” he said, urging towns that had such a designation to take three steps: admit, apologize and change practices.

Loewen had suggestions for business owners who wanted to build community, as the convention theme suggested.

“You need positive experiences

Steve Sugrim photo

David Greene, host of NPR’s Morning Edition, said he was fascinated by entrepreneurship ... and by MEDA’s work.

across racial lines,” he said. “Hire blacks, and not just one. Hire two, three or four people of color. Hire a posse. They reinforce each other and do better. Ignore standardized tests, which are racially biased. Expect good performance from everybody, including people of color. Expect them to do a good job.”

Such deliberate action had unintended positive consequences, he said. “Once you get right with racism you get right on other things, too. It will likely make you better in regards to sexism.

“Your diversity, your company’s diversity, makes you smarter. You get people who think outside your box.”

Popular journalist and radio

personality David Greene brought his engaging warmth and globe-trotting touch to the Saturday evening keynote address. Host of National Public Radio’s Morning Edition, he spoke on “Finding Strength in Adversity:

Tours provided a chance to see local sights like the Richmond International Raceway. From left, tour guide Jim, Dan Miller, Harry Enns, Spencer Cowles, Bill Gotwals, Ruth Leaman and Warde Hershberger.

The Stories of Some Downright Courageous Business Owners.” Greene’s assignments have included the White House, Arab Spring in Libya, Chernobyl and Hurricane Katrina. He served for several years as NPR’s correspondent in Moscow, after which he wrote the book, Midnight in Siberia: A Train Journey Into The Heart of Russia.

He acknowledged wistfully that the entrepreneurial gift was “something I don’t have” but he had been able to watch it firsthand, both as a journalist trained to listen to stories and as the husband of a woman determined to set up a restaurant in Washington, DC. He had long been fascinated by people who can battle back from adversity, from homeowners ravaged by Hurricane Katrina to a Kentucky boat builder laid low by a sour economy who proudly declared “making houseboats is in our blood.”

Greene said he felt “lucky to have met people like these, people in business who wanted to build something. They have helped me understand what it means to be an entrepreneur, and what it means to be a dreamer ... and what a successful enterprise can do for a community.”

His restaurateur wife, he said, had withstood criticism that she was naive, lacked experience and didn’t know business. “She followed a dream with such passion and perseverance and now is one of the hottest and most successful business owners in Washington, DC,” he said.

In Russia Greene had met entrepreneurs who defied all odds in building enterprises. One was a hotel owner named Svetlana, who daily battled corrupt local officials who harassed her in expectation of a bribe.

“This was her life, but she was determined to find a way and not to let the system get her down. When I think of the future of Russia, it’s people like

Steve Sugrim photo

If there were a prize for faithful attendance it would go to Ervin and Erma Steinmann of New Hamburg, Ont. This was their 40th consecutive MEDA convention.

Svetlana who give me hope.” fills me with hope and optimism.” Greene said he was “truly amazed” by the work MEDA did to The convention, MEDA’s promote entrepreneurship. Speaking premier public event, drew some to “a roomful of people who appre- 420 people this year, including partciate the art of entrepreneurship ... timers. Among them were stalwarts Ervin and Erma Steinmann of New Hamburg, Ont., who were attending their 40th consecutive convention. Local tours gave an exposure to area attractions, such as visits to the region’s colonial past, the Richmond International Raceway and a hands-on cooking class. Professional development and faith/business seminars covered topics ranging from cultivating leadership to skills sought by today’s employers. Several new features were added, such as a “dine around” Friday dinner in which groups of attenders visited local eateries together. Another was MEDAnext Talks, an afternoon of short TED-style presentations on a variety of topics such as use of social media; charitable giving trends; behavioral economics; impact investing; and creation care. Mennonite Foundation’s Mike Strathdee refines The next convention will his culinary skills during a visit to the Mise En Place be held Oct. 27-30 in San AntoCooking School. nio, Texas. ◆

Crowbar for the poor

Revenue was down but leveraging brought hope to more than 36 million of the world’s poor

The rustle sometimes heard at MEDA’s Annual General Meeting is the sound of eager businessfolk paging to the financial statement. For most of this century, those numbers have shown a happy bottom line.

This year gave some pause as MEDA reported that a “perfect storm” of challenges had combined to produce revenues considerably below budget.

Treasurer James Schlegel told the AGM that by numbers alone, 2015 was “a difficult year,” with contributions of $4.4 million down from targets and an operational deficit of $1.06 million. “This is something we haven’t been accustomed to in MEDA,” he said, noting a nearly dozen-year run of solid performance.

Key drivers of the poor results were transitions in large contracts, lower than expected private contributions and currency devaluations that put pressure on investment earnings. “It was a year of transition with some of our largest projects, such as the mosquito net project in Tanzania and the entrepreneurs project in Pakistan, coming to an end,” said Schlegel.

Numerous exciting new contracts in the pipeline had taken longer to gain approval from donor agencies and even longer to reach the active phase. “We expected a lag between old contracts ending and new contracts starting up, but this year the lag had been longer than usual,” said Schlegel. “That’s the reason for the losses.”

Still, he said MEDA had “a solid base of equity” and the future looked bright with numerous strong contracts signed and ready to start.

“As we get ramped up it will be a very busy year for staff,” said Schlegel.

While not denying the revenue was disappointing, he stressed that “the most important number is the 36.5 million families our efforts helped last year.”

MEDA board chair Bert Friesen concurred: “Although the year has had some challenges, we cannot lose sight of the great work MEDA we know this will not always be the case, and it is important to store up some reserves for future rainy days. Well, this year we obviously needed to dip into those stores.”

Sauder went on to report some of the many ways MEDA leverages for impact, “and why that makes us an organization that others wish to learn from.” He stressed that the leveraging was not the kind made infamous by the Lehman Brothers fiasco and the worldwide financial meltdown of years past, but rather a responsible business approach based on sound stewardship of resources that achieves the greatest impact for the maximum number of families. Falling back on his one-time role in hardware sales, he described it as “a crowbar that works for the poor.”

He reported that in the past year MEDA worked with 233 partners in 52 countries to help 36.5 million families realize healthier, more economically sustainable lives. Most of these were customers served by small and medium enterprises where MEDA has an investment through one of the Sarona funds, plus some 66,000 clients to whom partners provided access to markets, financial services and training.

“These numbers do not count clients of the organizations that we worked with in the past who continue to provide thousands of entrepreneurs with financial, marketing and training services long after MEDA is no longer directly involved,” said Sauder.

In the past nine months 18 new projects had been approved for a total value of $121 million, including

Steve Sugrim photo

MEDA’s success at leveraging for impact makes it “an organization that others wish to learn from,” said president Allan Sauder.

has done to help so many families improve their livelihoods,” he said.

President Allan Sauder observed that “as a business-oriented organization we take our financial reports very seriously, and it is a blessing to work with a board of directors who understand the ups and downs of business and that nothing goes up forever. In my report last year, I said we were grateful for a number of years of very positive bottom lines but that as a risk-taking, leading-edge organization,

some $21 million which MEDA will need to raise from private supporters as matching funds over the next four to six years.

“The future for MEDA is bright,” he said.

Sauder also highlighted impacts that were not so readily quantifiable.

One was the enduring success and achievements of IMON, a microfinance institution in Tajikistan that came into being with MEDA’s help (see sidebar article on page 12).

Sauder said that this summer he traveled to Ethiopia with the Canadian delegation to the Conference on Financing for Development spon-

sored by the United Nations and an International Business Forum sponsored by the UN and the International Chamber of Commerce. “Gerhard

God’s lever

To introduce the AGM theme, MEDA chief financial officer Gerald Morrison presented a meditation on leverage in the Bible — “how God used ordinary people to accomplish great things.”

That leverage, he said, began as early as Genesis, where Abraham and Sarah, seemingly too old to bear children, were blessed with a child (Isaac) from whom descended multiple millions “like the stars of the sky and the sand on the seashore.”

Other “levers” followed, like Moses (“one person, and a reluctant leader at that,” who delivered the Israelites from captivity) and David, who built a kingdom.

The New Testament, too, had stories of great miraculous acts created out of almost nothing, like five loaves and two fishes feeding 5,000, and the story of three servants and their talents.

What, Morrison asked, did the parable of the talents say about leverage? “Some of the parallels Pries of our partner organization, Sarona Asset Management, was on stage several times to talk about our work in impact investment,” he said. “Our pioneering work in blended finance was featured prominently — leveraging official development assistance with private sector capital and philanthropic sources to achieve the United Nations’ new Sustainable Development Goals.”

The conference was no small event, he said, with some 8,000 heads of state, ministers of development and finance, and heads of most of the world’s multilateral institutions.

“It was very gratifying to see that

are quite evident — invest what you have and multiply it; take your five talents and make five more, or in today’s money, take this $2 million and make another $2 million.”

He noted that the story was not told primarily to bankers and wealthy merchants, but to poor fishermen and tailors. “We know that Jesus was not talking only about money but about all the gifts we have received from God,” Morrison said. “Don’t hide your gifts, your resources ... but share them and there will be enough for all.”

That included hardships, which Morrison said could also teach important lessons. “When you encounter loss and hardship, as is almost inevitable in business, don’t be afraid, don’t bury it in the ground — learn from it and go on.”

While development work often felt unending, recent United Nations figures showed progress, Morrison said. • People living in extreme poverty have dropped by 50% since 1990, from 1.9 billion to 836 million and the working middle class has tripled; • Undernourished people in developing countries have dropped by half from 23% to 12%; • Strides were being made in education, gender equity, maternal health and child mortality. “Near and dear to our hearts at MEDA, 6.2 million deaths from malaria have been averted since 2000, most of those children under the age of five. MEDA was part of that.”

There was still more to do, and MEDA wouldn’t run out of work anytime soon, said Morrison. “Little by little we all can make a difference. Every life impacted is a difference made in the world.”

MEDA’s reach to more than 36 million families last year was “pretty good leverage for an association of 3,000 with staff of 300 and revenue of $18 million to work with.”

Moreover, he said, “Through all your business connections, employees and interactions with your community, the people in this room have touched hundreds of thousands of people.” ◆

there was considerable interest in our work over the past 60 years, and more recently with the Canadian-financed INFRONT project. This project is a unique combination of $15 million to provide a first-loss guarantee and enhanced returns to help attract private equity into the Sarona Frontier Markets Fund 2 LP, and $5 million to help MEDA and our partner, the MaRs Centre for Impact Investment, to provide technical assistance and mentoring to small and medium investee companies and equity fund managers. This model was touted as holding considerable promise to help stimulate the kind of private investment that will be required over the next 15 years to achieve the ambitious Sustainable Development Goals approved in September.”

Further on the subject of

impact investment, Sauder drew attention to this year’s Sarona Values Report, which noted that the 137 surveyed companies where MEDA funds are invested provided training to 12,869 employees and paid more than $120 million in taxes. Eighty percent of these companies reported that they are pursuing environmental objectives, and 66 percent are pursuing job creation objectives.

Sauder reported that MEDA staff and board members have been engaged in strategic planning for the next several years. Earlier this year MEDA received in-depth input from management expert Roger Martin, author of the book Playing to Win, which presents a new model for strategic planning focused on making choices.

“We examined our current strategy, outlined some possibilities for the future, and then examined them through the lens of reverse engineering — what would have to be true to make them viable. Six interdepartmental work groups tested the perceived barriers to success, including consultations with other organizations, funders and board members.

“I look forward to helping create an association that engages all of our people in new and meaningful ways as we work to create business solutions to poverty so ‘that all people may experience God’s love and unleash their potential to earn a livelihood’.” ◆

Bikers edge climbers for donor dollars

Two stars of the convention were Mary Fehr and Sarah French, who spent May to September cycling across Canada to raise money for MEDA’s GROW project (Greater Rural Opportunities for Women) in Ghana. Their infectious presentations captured the imagination (and generosity) of attenders as a good-natured competition for donor dollars emerged.

The women’s journey began in Victoria, B.C. and ended in St. John’s, Nfld., a total of 8,710 kilometers (5,400 miles). Initially they hoped to raise one dollar per kilometer, or $17,420.

“We suggested $150,000 might be a better target,” said Dave Warren, MEDA’s chief engagement officer.

By convention the pair had raised $220,000. They declared a wish to surpass the amount raised the year before by MEDA president Allan Sauder and his climb of Mt. Kilimanjaro, which then stood at $286,000 but was bumped up by additional last-minute donations. Fehr and French spontaneously asked if 60 convention attendees would support Bike to GROW with $1,000 pledges.

“We want to win, really bad,” they said.

By next morning, the GROW commitment had risen to $311,000, eclipsing the Kilimanjaro total of $298,000.

Fehr and French told the audi-

Mary Fehr (left) and Sarah French hoist their bikes to celebrate arriving at the Atlantic Ocean after a grueling cross-Canada trek.

ence of the physical and mental challenges they faced. “When things got tough we would think about the women of Ghana and how hard they have to work every day,” said Fehr. “With that motivation there was no way we were going to give up.” ◆

Long tail of impact

To illustrate enduring impact, Allan Sauder pointed to the Asian country of Tajikistan, home to a thriving microfinance institution that received timely help from MEDA. A recent tour with past and present board members had been initiated by former board director Verda Beachey to showcase the impact MEDA leaves behind when it moves on.

For years Tajikistan was the poorest of the former Soviet Union’s republics. Independence in 1991 brought hope, but years of civil war and economic collapse reduced most of its eight million people to poverty. MEDA responded with a $4.5 million project (2004-2008), working with 3,000 smallholder farmers to boost fruit and vegetable production.

IMON, a new microfinance institution (MFI), was started by Sanavbar Sharipova and Gulbahor Makhkamova, two women who had lost their jobs after the fall of the Soviet Union. They first started an association to teach business skills to women, then established a small loan fund which grew into IMON.

MEDA connected with the association to introduce a rural portfolio, giving IMON an agricultural foothold. MEDA helped IMON evolve into a commercial microcredit organization, bringing the tools to create a loan product that helped IMON become a vital partner to farmers. Until MEDA came along, no one was lending to smallholder farmers in Tajikistan because it was thought to be too risky.

“MEDA was also the first to directly invest in IMON’s banking vision,” Kim Pityn, MEDA’s chief operations officer, told the AGM. “We currently have a 10 percent ownership stake. We took the risk and put money into IMON when no one else would, because we could see the potential.”

MEDA has had a seat on the IMON board of directors since 2004. Pityn, who is chair of the board, was instrumental in bringing major new investors: the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, a Dutch government fund, and Triple Jump, an impact investment fund.

“IMON is now busy preparing to become a regulated full service bank early in the new year, so MEDA’s impact continues at yet another level,” Sauder observed.

Today, IMON offers loans for businesses, agriculture, consumers, start-ups, rural household development, machinery and home improvement. It profitably serves over 100,000 clients through 26 branch offices and 113 sub-offices. It manages a loan portfolio of $135 million (average loan size of just over $1,000) with an at-risk rate of below one percent. Women account for 35 percent of borrowers. IMON, now the largest MFI in the country, received a “best taxpayer of 2013” award. Moreover, said Pityn, it received a Social rating of A+ from industry watchdog Microfinance Rating.

“During our visit Sanavbar and

Today IMON manages a loan portfolio of $135 million, serving more than 100,000 clients through 26 branch offices and 113 sub-offices.

Gulbahor repeatedly emphasized the critical role that MEDA played in establishing IMON,” Pityn said. “Many of the key management positions among IMON’s 2,000 staff are filled with MEDA staff from our earlier agricultural project.” Beachey said one IMON client the tour visited had been living in a mud hut but with IMON’s help built homes for himself and his two sons. He was able to send the sons to university and they have since returned to join the family business. The tour also visited a farmer in a remote area of the rocky country who borrowed $5,000 to buy five hectares of land. “With a less than modern tractor and a few pieces of equipment he leveled the land and picked up the stones,” said Beachey. “He now has tomatoes, potatoes, onions, strawberries and apricot trees as well as some livestock. He has been able to build a well and watering system for his crops. He shared with us that because of that loan he is able to provide for his family, provide employment to others, give food to the poor and give money to the local orphanage.” ◆

Business for the greater good

Can you grow a business while pursuing higher purposes like the good of employees and communities? Yes indeed, according to the principals of three family-owned companies at MEDA’s convention.

The plenary lunch session featured families who view their enterprises as a calling and central to their stewardship. • Faith and Tim Penner of Harper Industries, which manufactures agricultural, hydraulic and turf equipment in Harper, Kan. • Ed Shenk (and executive Thomas Rose) of Weavers Hardware Company, Fleetwood, Pa., which operates two retail hardware stores and a commercial sales division. • Marcus Shantz and his cousin Sheila Shantz who operate numerous businesses in St. Jacobs, Ont., including the St. Jacobs Farmers Market.

Moderator Dave Warren, MEDA’s chief engagement officer, queried the panelists about their greatest challenges and most meaningful experiences in business.

A common challenge was to listen to and respect alternate local viewpoints.

For Ed Shenk, whose retail establishments serve a community with “horse and buggy neighbors,” it was important to talk to different people and listen carefully to their concerns. “What does it mean to respect other people’s views?” he said. “How do you allow everyone to have their sabbath?” His colleague Thomas Rose added that dialogue was important.

Marcus Shantz agreed that “learning to listen” was critical, especially in his business which includes tourist development and “the community doesn’t always like everything you do.”

Sheila Shantz spoke about a fire that destroyed the market two years ago (and reopened last summer). She was amazed by the outpouring of support as people offered to help. She said she “never would have imagined” the strong sense of ownership evident among local people and their degree of family-like loyalty to the vendors.

Shenk said one of his most meaningful experiences was a company Christmas event for employees and he was struck to realize that “the way I run this business impacts all of their lives. It was a big revelation for me.”

Tim Penner related an example of “the serendipity that happens” in business.

One day a member of Harper’s shipping department pulled him aside and with tears in her eyes said, “Tim, I want to thank Harper Industries for this job.”

“Say more,” he said.

“Well, we live in a very small house right now,” she said, “so small I can’t bring my wider family over to entertain. I’ve always had a dream for this one house, and that house is now for sale. I went to the banker and he said, ‘You now have the financial means to do it.’ Now I can have my family around my table. Thank you.”

Penner concluded, “There are times in business that are very exhilarating, and you say, ‘Thank you, God’.” ◆

, Waterloo, Ont. Photo courtesy The Record

Meaningful moments: Sheila and Marcus Shantz at their farmers market during reconstruction after a devastating fire in 2013.

The difference between us and poor people

Most poor people don’t want handouts; they want opportunities to lift their families out of poverty.

by Joyce Bontrager Lehman

Joyce Bontrager Lehman has worked for MEDA in Afghanistan, then with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and now is a technical advisor on global financial inclusion. Here is an abridged version of her Sunday morning keynote address.

Poverty is one of the most persistent and vexing of global issues. Before we all go our separate ways for another year I’d like to reflect on the lives of the people who live in poverty and who know so much more about it than we will ever know.

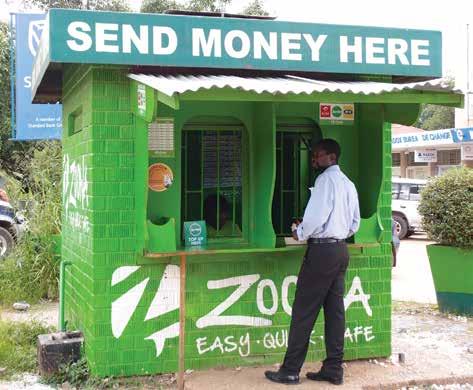

For a decade and a half I’ve worked with organizations that want to provide poor people in the developing world an opportunity to lift themselves out of poverty. In my case, the specific mechanism is to provide access to the same level of financial services we in the rich world take for granted. I started this work with MEDA in its microcredit program, but over the years have also worked with other organizations to provide a broader range of services: micro savings, micro insurance, and most recently, access to payment and transfer services using mobile phones and other digital mechanisms.

One of those organizations was the Bill & Melinda Gates Founda-

tion whose primary objective is to give every person the opportunity to live a healthy productive life. What struck me when I first arrived at the foundation was its five-word core value: “All Lives Have Equal Value.” Full stop. No exceptions, no Steve Sugrim photo conditions, no caveats. “ALL Lives Have EQUAL Value.” Providing increased economic opportunities for poor people had already been a passion of mine, but to be faced with that statement every day at the office, on our screen savers, seeing it carved into the wall of the new campus building I entered each morning, and hearing it repeated with every speech given by the leadership, I was challenged to think differently about the global poor. It’s a powerful statement, and while we all know and believe that every person is equal in the sight of God, I had to wonder whether I really believed it — or more importantly, lived it. This large non-sectarian organization caused me to not only think more deeply about the people I was so passionate

Why aren’t we poor? Because we were born lucky, about “helping” but also to set said Sunday keynoter Joyce Bontrager Lehman. aside my own preconceptions

Everyone has a story, like the driver in Lusaka, Zambia, who now has a better way to send money home to his family in the north.

and really listen to their voices.

There really is just one reason

why a person is poor. It is because he or she doesn’t have enough money to meet their basic needs, and we do. Poverty is an economic circumstance, nothing more. You might then ask, “why do they not have enough money.” To put it simply, it’s largely a factor of where and to whom they were born. We are among the fortunate.

There are now over seven billion people on our planet; two billion of those live on less than $2 per day, so a family of four has income of less than $250 per month. That is the level typically used to define the global poor by the World Bank and other large development organizations. Another 1.5 billion people live on less than $4 per day and are at constant risk of falling into poverty because they have no margin to deal with the inevitable shocks that come their way, whether it is a health crisis, crop failure, natural disaster, or political instability. More than half of the people in our world live with these uncertainties every single day.

What is our picture of the global poor? Is it the crying children with dirty faces who appear on TV fundraising ads? Is it the tens or hundreds of thousands living in refugee camps in post-disaster or post-conflict situations? Both are very and tragically real, but all those millions together are only a small part of the poverty picture that is 3.5 billion strong.

The fact is this: most poor people in the world work very hard and make very difficult choices to keep it together and just barely at that. Most do not want charity or handouts. They don’t want “help,” they want opportunities to help themselves and lift their families out of poverty. So, rather than feeling pity or even worse, being patronizing, we should view each person as an equal. Furthermore:

We should have admiration. Most of the two billion who live on less than $2 per day still manage to put food on the table, keep a roof over their heads, plan for medical emergencies and some even save for old age. Research for a book called Portfolios of the Poor recorded every single transaction of 250 households in three countries for one year, reporting on the tiniest financial transactions — a few cents each — and found that most poor people have surprisingly sophisticated financial lives, saving and borrowing, pushing and pulling cash transactions with an eye to the future and creating complex “financial portfolios” of formal and informal tools. You have to be pretty smart to manage on $2 per day because of course the $2 does not come in every day — a smallholder farmer may get her income only several times a year after harvest. I wonder how many of us would do under those circumstances.

We should have understanding. I once sat next to a woman at a charity event for a different development organization where her husband was speaking. She said the problem with helping poor people was that there were already too many in the world and all the aid money was encouraging even more. I was too stunned to speak! What I should have said is that we know many poor parents do indeed have a lot of children to ensure that at least a few of them will survive to adulthood and care for them when they are old. But what we also know, based on research, is that where the global mortality rate for children under five has declined, the size of families has also declined. As families feel more financially secure and as women in particular become better educated, birth rates decline. We need to understand the circumstances under which decisions are made, and if you are inclined to make that kind of statement, you really must understand the facts. That’s what I should have said.

We need to trust. We need to believe in the ability of poor families to make appropriate decisions. It is a good sign that many international aid organizations, starting with the World Food Program in Pakistan, now give cash rather than commodi-

ties for relief in post-crisis situations, whether they come from natural disaster or man-made conflict. Not every family needs the same thing; some do indeed need food, but others need to rebuild or improve their homes; still others want to buy inventory to restock their shops. Giving cash not only permits choice but also stimulates the local economy with the purchases people make with their cash. I can’t tell you how often I’ve been asked — what if the cash is not used for the purposes intended? Intended by whom — us? We need to trust that the family itself knows more about what they need than we do.

We need to be humble. We should never forget that we are rich not because we are smart or good or work hard — all of which may be true — but rather because we are simply fortunate. We are fortunate to be born in a place with infrastructure, education and the electricity to read and study in the evenings, health services, clean water and sanitation facilities. It is appropriate to feel grateful humility; in fact we should wake up every morning with hearts full of gratitude. But it is NOT appropriate to think that therefore we can tell others how they should live their lives and what choices they should make. We do not walk in their shoes.

We need to have respect. There is no question that people living in different parts of the world have different traditions, beliefs, cultural practices, food and clothing. But we all have the same basic aspirations. We want to support our families, we want our children to be healthy and educated, we want to live in peace and practice our faith without persecution or strife. In this there is no difference and we need to view each person with the respect we want for ourselves.

I still travel to the developing world every few months and I like to speak with people I meet along the way, like drivers and hotel room attendants. Everyone has a story to tell, and the stories often follow a pattern, like the driver in Lusaka, Zambia, who came to the capital to work and sends money home to his family in the north. I have both a personal and a professional interest — how does he send the money and how much does it cost him? For some time he used a Western Uniontype transfer service, but then Zo’ona (a mobile money provider) was established with MEDA’s support, and now he finds that less expensive

You have to be pretty smart to manage on $2 a day, as two billion of the world’s poor do.

and more accessible. Families often separate by necessity so that one member can leave to find work and send money home.

These conversations are both interesting and instructive. One of the most profound lessons happened when I had a one-day stopover in Dubai on my way home from Kabul. I decided to visit the hotel spa, a microcosm of many of the wealthy countries in the region where most of the manual labor and service jobs are carried out by migrants. In the spa that day were 6-8 women from the Philippines who were doing the manicures and pedicures. I knew they were probably living together in one or two rooms to save as much money as possible. I asked the young woman working with me to tell me her story.

She is a single mother with a 10-year-old son, and there is not enough work available in her home country to permit her to both provide for herself and her son and save for his education. She lived for that dream — that her son could continue his education. She had been in Dubai for eight months under a three-year contract, and she would not see her son for that entire period. He lived with her parents and she sent money home each month for his support, worked as many hours as possible, and spent as little as possible and saved whatever was left. I tried to imagine what that would be like.

When she was finished, I gave her a tip larger than I typically would, and I could tell by the way she said “Thank you” that something was a bit off — she seemed almost embarrassed. I quickly blurted out: “It’s for your son.” She stood up from the stool, looked directly into my eyes and said, “Of course it’s for my son; it’s all for him.” All of it — the time apart, the long hours, the cramped living conditions — made what I did almost irrelevant. As I was leaving to go back to my room, I realized I had broken my own travel rule — I never give money as charity, but am willing to pay for services no matter how small — for someone to spend time with me or give me permission to take their picture. What I should have done was to thank her for a great manicure that I could tell would last a long time and especially to thank her for taking the time to talk to me. If I had said that, then the money would have been payment for her services and not charity for her son — it was her job to provide for her son, not mine.

But I had reacted to her story on an emotional level, and what I did was to make me feel better as though that would fix everything and I no longer needed to care. Too often we (and when I say we, I mean me most of all) do the right thing for the wrong reason or the wrong thing for the right reason. It’s really hard to get it all right all the time.

And while not all of us have the inclination or the opportunity to interact directly with the global poor, the very least we can do is to acknowledge the equal value of every life and to do so with admiration, trust, understanding, humility and respect. ◆

Reaching out to Cuba

Recently relaxed regulations allowed visitors to meet local entrepreneurs and get a feel for what might become possible.

by JB Miller

When most people think of Cuba and business, they envision a country where virtually everyone works in government-owned enterprises, and for most of the period since the revolution in 1959 that has been reality. However, more recently, the government has relaxed some of the regulations. Today there are signs of entrepreneurial life with 181 approved business ventures, including auto mechanics, computer repair, restaurants, bed and breakfasts, and farming. Estimates range from 500,000 to upwards of one million people involved in these activities in a country with a population of about 11 million.

To better understand these changes, 18 persons from the U.S. and Canada visited Cuba in November under a “people to people” program, one of 12 purposes allowed by the U.S. government for legal travel to the island. The group traveled under the auspices of Witness for Peace with support from the MEDA Sarasota chapter. Jim Miller, chapter president, noted that the chapter has been interested in a connection with Cuba for more than two decades. “Our primary objectives were to better understand entrepreneurial activity on the island and take a tangible step forward by exploring a potential project partnership between an organization in Cuba and the local chapter.”

The visit included meetings with entrepreneurs who shared freely of their challenges with running their own businesses in a highly restrictive environment. Difficulties in finding raw materials and spare parts were recurring themes. Obtaining spare parts for auto mechanics is particularly challenging. While approximately one-third of the cars on the road are pre-1960 U.S. automobiles, the trade embargo, or “blockade” as the Cubans call it, makes it nearly impossible to bring parts in from the United States. In spite of these challenges, the owners did not seem

Nelson Hoover photo Nelson Hoover photo

Havana is like a vintage auto museum: a third of the cars are pre-1960 U.S. models, many in pristine condition.

interested in returning to a government job, citing the opportunity to improve their lifestyle and set their own schedules as big benefits.

Restaurant ownership was

one of the first private enterprises allowed. Known as paladars, these establishments operate out of people’s homes, although once inside, there is little sense that these are private residences. One particular establishment, Paladar Los Mercaderes, located in Old Havana, seats 50 people. The cuisine and ambience rivals any major city restaurant. The owner, Yamil Alvarez, mentioned that the main dining room, a highceiling nicely appointed room, was once his bedroom. Seafood is bought directly from fishermen; vegetables for the restaurant are grown on a family farm outside the city.

There is little evidence of any wholesale businesses that support entrepreneurs, regardless of the business. This was particularly evident

Furniture maker Ariel Moriyon (center, in turquoise shirt) tells visitors what it’s like to run a business in Cuba.

The home of furniture maker Ariel Moriyon, which his wife operates as a bed & breakfast.

during a visit to the carpentry shop of Ariel Moriyon, an accomplished cabinet and furniture maker. Outside the workshop was a large eight-foot log that he will eventually cut and use in his business. A newly completed bed frame was ready for delivery. When asked what he worries about, he said wryly, “I worry that IKEA or Walmart is going to come to Havana and put me out of business.” Farming, during the period of Soviet influence, was primarily done

A furniture maker quipped: “I worry that IKEA or Walmart is going to come to Havana and put me out of business.”

on large industrial farms with overfertilization damaging much of the farmland. Today, however, many farmers are willing to try new techniques including organic farming, and utilizing vermiculture (worm farming) and composting to make natural fertilizer. During a visit to a family farm outside of Santa Clara, the farmer spoke proudly of the

David David photo kitchen stove and oven that was fueled by methane produced from the hog-raising operations.

While Cubans have limited access to the internet, entrepreneurs catering to tourism are well aware

of marketing and websites that can promote their businesses. During one night at a bed and breakfast in Santa Clara, the owner insisted that guests write a recommendation on the Trip- Advisor.com website and that a four or five star rating was preferred.

Allan Sauder, president of MEDA, participated in the trip. “We met a number of very hardworking and entrepreneurial Cubans,” he said, “and it was clear that most business activity is still closely tied to the government at some point in the value chain.” As for MEDA’s plans in Cuba, he stated, “MEDA does not currently have any specific program plans for Cuba. As the environment in Cuba evolves, we will continue to watch for opportunities that may arise to engage in developing ‘business solutions to poverty’.”

Many Cubans seem optimistic about the future. They have endured many hardships over the years, but they are a warm, friendly, resilient people, and proud of their heritage. They are happy to see improving relations with the United States. During the visit, representatives from the MEDA Sarasota chapter met with local people to explore project possibilities for the chapter. “We believe these conversations were a positive step forward,” Jim Miller said, “and we look forward to more conversations.”

To further strengthen the relationship with the Cuban people, the MEDA Sarasota chapter is exploring the feasibility of organizing trips to Cuba beginning in 2016 under the “people to people program.” Interested persons should contact the MEDA Sarasota chapter at http://www. meda.org/sarasota-chapter. ◆ JB Miller recently retired to his hometown of Sarasota, Florida, after a 24-year career at Everence.