49 minute read

Soul enterprise

In the beginning there was work

Advertisement

“Are you a Mennonite?” the elderly woman asked Matt,* a financial planner and longtime MEDA member. “I want a Mennonite to handle my money.”

Matt met Deborah a number of years ago when she came to him to help manage her investments. Ten years later, when she was doing her Will, she asked for his advice so she could leave a portion of her estate to charity to offset her tax liability.

“When I told her of the work of MEDA, and the fact that it was run by Mennonites, she chose it as the recipient of her bequest,” Matt says.

Deborah was not a Mennonite, but she had fond feelings for them.

During a rough spot in her early life, authorities had taken her young son and placed him in foster care while she got her life back together. The foster family, who were Mennonites, treated her son well, and Deborah was deeply gratified by the wholesome environment he enjoyed. She liked the family’s values and what they had done for her child.

Over time her life picked up, and she remarried and got her son back. But she never forgot the caring Mennonites.

Nearing the end of her life, she wanted part of her estate to help others in the same spirit that her family had been helped. She wanted Matt to find a good home for her money, just as the Mennonites had given a good home to her son.

* Names have been changed to protect confidentiality

Our study group just started reading through the Old Testament. You know

what struck me when we read through Genesis?

God created us to work.

No sooner did God form Adam (Genesis 2:6) than he “put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it.”

You’ve heard that before. But sometimes we miss the order.

Often we believe that work was handed down by God as punishment for disobedience (Genesis 3). But no — God created us to work, then sin entered the world. We had the perfect world but then it all changed. Enter computer crashes, viruses, technical difficulties and all those other thorns.

Culture has accelerated this warped thinking that work is our punishment. Commercials and movies ingrain the idea that the 5-6 days of work are just to get us to the weekend.

In our attempt to put a Christian spin on it we further miss the point. We somehow think the workweek is our step to get to the real worship on Sunday morning.

Where did things get so out of order? When did we believe that somehow volunteering on a Wednesday night with the youth is important enough to overlook the 40-50 hours of opportunity in the office?

I love getting involved in opportunities to serve in the church, but I think we could all use reminding that in the beginning God created us to work. When the world was still perfect, before sin entered the world, our primary act of worship was working in his garden.

Even God modeled that for us by spending six days working and finally resting on the 7th .

So tomorrow, I head off to work. To care for his creation. His kingdom. Hopefully I can remind myself that how I go about it might be the greatest act of worship I do all week. — Justin Forman

“If you want people to listen, you have to have a platform to speak from, and that is excellence in what you do.” — William Pollard, former CEO of ServiceMaster

A taste of heavenly hash

John Harrison has what many people would consider a dream job. He’s the official taste tester for Dreyer’s, America’s largest ice cream company.

Every day he tastes his way through some 60 samples — from vanilla bean to black walnut. He takes a spoonful in his mouth, smacks and swirls it around carefully, absorbing the flavor and bouquet. Then he spits it out. That part isn’t always easy, but he has no choice or else he’d get too full.

Like any expert, he has to keep “fit” for the job. That means avoiding foods that might clog his taste buds, like onions, garlic and spicy foods.

The stakes are high. A bad batch of ice cream can ruin a company’s reputation. “Ice cream companies have closed down in the past because of flavor mistakes,” he says.

Over the years Harrison has tasted and approved 200 million gallons of ice cream. His tongue is insured for $1 million.

A dream job? Harrison thinks so. In fact, he thinks it is a calling from God. He grew up in the dairy business and wanted desperately to get out and become a doctor or lawyer.

But that wasn’t to be, he says.

“God called me when I got out of the dairy industry and said, ‘Get back in the business I trained you up in.’”

Dreyer’s called three days later.

“Thirty-nine years ago I put my future in God’s hands and he has never disappointed me,” says Harrison. “God has put me in my position. Anytime he’s ready for me to leave I’ll be out and on to something better.” (World magazine)

Sermons that connect

What kind of sermons do people want to hear?

United Church minister Sharon Wilson wants to know, and is devoting a threemonth sabbatical to try to find out.

“I find the people in my congregation to be intensely interesting,” she told religion writer Brenda Suderman. “Their lives fascinate me. I want to be able to minister to them more effectively.” The veteran Winnipeg minister regularly tries to make Sunday-Monday connections in her preaching. Over the years she has often accompanied parishioners to their jobs for a day to better understand their weekday world and the kinds of pressures they face. These have included a hairdressing salon, auto impound lot and a radio station. The visits not only enrich her sermons, they also help the visited parishioners get a better grasp of how their faith connects with their work. (Win‑ nipeg Free Press)

Overheard: “Barn’s burnt down — now I can see the moon.”

Poor need a place to stash their cash

Savings – another rung on the microfinance ladder

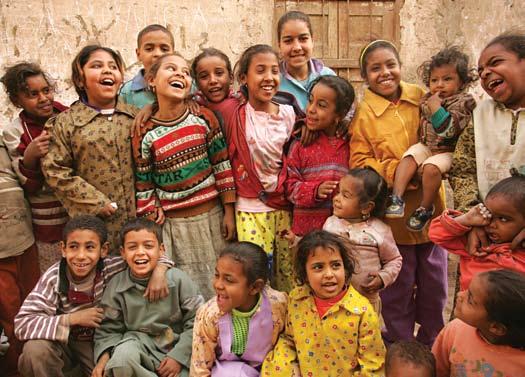

Imagine you’re one of the two billion people in the world who earn less than $2 a day. It might seem laughable that you’d need a place to save money.

But you have to put a bit aside, even if only pennies a day, because maybe your daughter is starting school and you’ll have to pay the annual fee.

Or you need to build up your emergency fund for when someone gets sick. A few saved dollars to buy medications to treat diarrhea or malaria can mean the difference between a child’s life and death.

So where do you put your money to keep it safe? Your village has no bank but it might have a local savings collector who will hold your money — for a fee, not like North Americans who get paid interest to salt their money away.

Where do you keep your cash if you live in a hut with no doors or windows? Hide it under your mattress, if you even have one? Put it in a tin can and bury it outside, and hope the next flood doesn’t wash it away?

You can’t leave it lying around, because your husband might come home drunk one night and want it to buy more booze. Or your relatives might drop in from another village with a tale of woe, and in your culture it is unthinkable to not share.

A safe place to keep money, even small amounts, can help the poor spin out of the spiral of debt.

to Lift the World Out of Poverty. Development agencies are increasingly finding ways to add a savings component to their microfinance methodology. A seminar at MEDA’s recent convention in San Jose underlined the need. It was led by microfinance expert Joyce Lehman, former MEDA staffer in Afghanistan who now works for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She said the number of people living on less than $2 per day is now estimated at 2.5 billion, and most of them are regarded as “unbanked,” meaning they have no access to even basic financial services. “Contrary to what we might think, the poor have just as much “Can you imagine need to manage their financial lives as we do,” she said. “Can you imagine how smart you how smart you have to be to manage living on an average of $2 per day?” have to be to A new emphasis in development circles was “financial inclusion,” as manage living on agencies sought to make savings another rung on the microfinance ladder, an average of $2 Lehman said. “We have learned that when microfinance institutions are able to offer per day?” savings products as well as loans, the demand is four or five times what it is for credit. There is more demand for a safe place to save The concept of savings for the poor goes far money than for a loan.” back. In the late 1700s, pioneer missionary William Carey To illustrate the pent-up demand, even among the used a form of a Savings and Credit Association (SCA) in very poor, she described how an African widow was saved India to empower women. “Carey agreed with Solomon from ruin by a mobile bank that offered a “smart card” that unless individuals have the power to save, they risk with a thumbprint safeguard. forever being slaves to lenders (Proverbs 22:7),” writes When the woman’s husband died she became, as Phil Smith in The Poor Will Be Glad: Joining the Revolution was the custom, the property of his brother. The brother

photos by Ray Dirks

took her smart card and tried to empty her account, but was foiled when his thumbprint didn’t match. Word of this widow’s “victory” got around, and the next time the mobile bank came to her area 400 women lined up to get their own smart cards.

“It is now the gift of choice among young brides,” Lehman said, adding that such innovative approaches could “turbo-charge” access for remote regions. but these are changing in a number of countries. This recent shift in the regulatory requirements is opening the door to real opportunities to partner with large microfinance institutions (MFIs) who reach hundreds of thousands of clients in a number of countries.”

Several of these large in-

The whole area of “informal” sav-

stitutions have turned to MEDA to help them develop savings products ings is gaining momentum in Africa and else- and begin the process of transformwhere, says Julie Redfern, MEDA’s director of ing themselves into banks. “There microfinance. aren’t a lot of people out there who

“Just like everyone else, poor people need a know how to do this, so we have a wide range of financial services that are conve- big opportunity in this area,” Rednient, flexible and reasonably priced,” she says. fern says. “Access to savings, money transfers and insur- “There aren’t a MEDA’s in-house expert on ance are all needed.” deposit mobilization is Ruth Jacobs,

Some of the methods being promoted, lot of people out a former banker, who has carried out however, are not much beyond a “cash box” several contracts to assist emerging approach that has been around for many years, there who know savings institutions in places like AfRedfern says. “While the demand for savings ghanistan and Pakistan. MEDA also products globally is very high, the quality and usefulness of current savings products for the how to do this, has a financial stake and governance role with Fonkoze Financial Services, poor is still questionable.” MEDA has avoided highly visible products so we have a big the largest MFI in Haiti with 130,000 savings accounts. like mobile banks but has quietly worked at behind-the-scenes approaches which have made opportunity in Redfern says another emerging area of attention is education around it an emerging leader in the field of deposit savings — how you teach savings to mobilization. this area.” people for whom this is new.

“Our recent involvement in savings has MEDA has been working at this been on the more formal side with the microfinance through its new YouthInvest program in Morocco and sector,” says Redfern. These have included introducing Egypt, where a whole generation of young people have savings products for newly regulated microfinance institu- not been able to have their own savings accounts and are tions. thus novices to the practice.

“I am a stickler for wanting savings to be intermedi- “We think our deposit mobilization and transformaated by organizations that are regulated and authorized tion work has the potential to reach between 300,000 to provide this service,” she says. “Until now, the major and 500,000 underserved poor clients over the next three obstacle to deposit taking has been national regulations, years,” Redfern says. ◆

photos by Ray Dirks

Coming clean

Addicts aren’t the only ones who need to face the growing scourge of substance abuse

by Don Mundy

It can be a manager’s worst nightmare: how to deal with an employee who clearly has a drug or alcohol addiction. To help members of the work community better recognize and handle substance abuse situations, Don Mundy inter‑ viewed Dr. Ray Baker, a leading British Columbia expert on the subject of drug and alcohol addiction. He discovered some surprising things about just how widespread the problem is and learned some helpful advice for those fac‑ ing the dilemma of whether to “rat out” a co‑worker.

Don: How prevalent is the problem of drug

and alcohol use and abuse in the workplace?

Dr. Baker: A general rule of thumb is that close to 10 percent, one worker in 10, is going to have a substance abuse disorder. That varies depending on the culture. There are certain high-risk trades or occupations or age groups. For instance, construction workers are found to have a slightly higher than average propensity toward abuse. Physicians are right on the average, and there are certain groups that are less likely to have addictions. Blue collar workers, outdoor workers, and people who work in the food and entertainment industry are more likely to have issues.

Don: You mentioned physicians. You mean to

say that doctors have as much substance abuse issues as the rest of society?

Dr. Baker: That’s right. We are right on the average as far as statistics go. It’s about one in 10.

Don: Many of our members work in places

that would be considered high risk. What are some of the signs that would indicate someone has shown up to work under the influence of drugs or alcohol?

Dr. Baker: Well, the big flags are if the person you’re used to interacting with changes all of a sudden, if they become emotionally volatile or erratic in their behaviour or performance. There are many other things that can cause this, but as a person develops a problem with addiction, that erratic “pretend performance” and behaviour becomes obvious. If a person shows up to work and they’re impaired, they may slur their words and look dishevelled or smell of alcohol or marijuana, but often there will be less specific or more general changes that alert you to the fact that something is wrong.

Don: You also mention that people withdraw

or isolate?

Dr. Baker: Yes, or social withdrawal. People with addictions tend to want to get away from other people where they are not being observed or scrutinized. There are also physical symptoms of withdrawal, and often after weekends people will be tremulous or look tense. Sometimes if they’re developing a problem they’ll find ways to use even at work. For instance, they might go off for a bathroom break or a coffee break, and when they come back they look visibly relieved because they are no longer in withdrawal.

Don: In the past, many people, especially in

unionized environments, found it hard to confront someone who they suspect has a problem with addictions or who comes to work and might be impaired. No one wanted to “rat out” his or her fellow workmate. What advice can you give to people when they come across a situation like this?

Dr. Baker: At an individual level, you’ve got to know that the person with addictions can’t see how big the problem is. They often can’t take the necessary steps. By covering it up you’re doing what’s called enabling. Not only are you making the workplace a dangerous place where somebody might get killed, but you may be the only person in a position to say something to somebody to do something. The person with addiction loses the feedback that they need to make the change. They really need to hear that you’re aware, you care, you’re concerned. Is something wrong? Are you sure you’re okay? So you need to confront them.

But at an organizational level, companies need to develop programs that become proactive in early prevention and early identification of problems with addictions. Organizations can educate themselves and their people about how common it is, what it looks like, the fact that it’s a disease, that it’s not a weak or defective character or personality, and that really good help is available. It’s not the end of the road for a person with addictions. It’s just the beginning of an improved life if you can assist them getting into recovery. The worst thing you can do is to cover it up and look the other way.

Don: Some businesses are

“The person with addictions can’t see how big the problem is.... The worst thing you can do is to cover

quite small and it might be difficult it up and look the for them to implement programs like these. What do you suggest for other way.”them?

Dr. Baker: Well, as an occupational professional, I end up frequently working with that type of small business. I’ll get a telephone call from a desperate manager or owner saying, “What should I do?” Basically, we walk them through what their obligations are and what their liabilities are and help them resolve the problem by facilitating a road map for resolutions. We can quickly evaluate the person, find out the appropriate treatment if they need it, and then paint out a simple plan for resolution. We can give the person a road map to follow to choose to get well or choose otherwise, but one way or another, there has to be a resolution to the problem because it can’t be allowed to continue. Don: What about workplace culture? Here

in BC there are more than a few workplaces where drug and alcohol use is imbedded in the culture. What can our members do to begin to change the culture where they work?

Dr. Baker: I think unions, especially unions that have taken leadership roles in the safety movement, recognize that attitude and cultural change is possible; it just takes awareness. We’ve seen dramatic cultural change around the acceptability of using alcohol at work or during events at work or being impaired at work. The most effective programs of change participate in an educational process where everybody becomes aware. They de-stigmatize or take the shame away from addictions. They allow it to come forward, and they show that they care. As individuals, our attitude is everything. We need to model acceptance and support but also firmness. Being a good union member when you’re dealing with a person with addictions is sort of like being a good parent. You have to be willing to set boundaries and be clear about what you’re willing to permit and not permit, especially when safety is involved. And that’s contagious. It spreads as people realize that this is a safe and healthy workplace where we care about our fellow worker, and we are not going to tolerate unsafe, irresponsible behaviour, even if it’s caused by an untreated disease. We insist you address your problem, or don’t keep coming here because someone’s going to get hurt.

Don: On a bigger scale there are some initiatives that CLAC as a whole is working on to address the drug and alcohol problem. From your perspective, what role do you see the union taking?

Dr. Baker: Unions can help employers become aware of best practices. I know that your organization is researching and developing best practices and policies where they can actually provide a toolkit and work with employers. In the workplaces that are the safest with respect to substance abuse disorders, there always has to be cooperation between union and management. It’s a win-win. This is an area where differences can be put aside. It doesn’t have to be polarized, because employers and unions have exactly the same goals around this and that is healthy, safe workplaces. ◆

Dr. Ray Baker is a physician certified in both family medicine and addiction medicine. As assistant professor, he designed and instituted the first comprehensive addiction medicine curriculum at the University of British Columbia medical school. He is the medical director of Healthquest, which helps individuals and organizations solve health problems such as drug and alcohol dependency and addiction.

Adapted from an article by Don Mundy published in the Guide, magazine of the Christian Labour Association of Canada (CLAC), a national independent labour union based on Christian social principles (www. clac.ca).

MEDA in San Jose: Frontiers of innovation

Can capitalism close the gap to benefit the poor?

If you want to talk about the future, there’s no better place to do it than California. Better yet, why not Silicon Valley, where the heartbeat of American ingenuity throbs loudest and where, according to legend, the future always wins.

With a theme of New Frontiers: New Solutions, it made plain sense to hold MEDA’s 2009 Business as a Calling convention Nov. 5-8 in San Jose — ground zero of innovation and the Disneyland of the ecofuture. If new frontiers were to be found, chances are they would have resonance here.

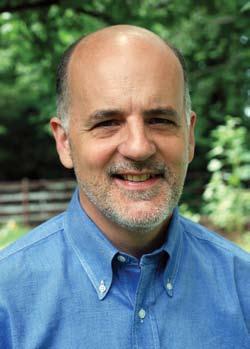

And who better to articulate its dimensions than Stephen Kreider Yoder, the San Francisco bureau chief of the Wall Street Journal, who is not only an authority on the high-tech mecca but a Mennonite, to boot.

To the delight of many listeners, Yoder began by lodging his professional cache solidly in the Mennonite firmament. “I got here because of my Mennonite world,” he said.

Yoder explained that after attending Goshen College, he and his wife had moved to Japan in the early 1980s and a year later the opportunity to work for the

Stephen Kreider Yoder

Journal “fell into my lap, almost by accident.”

The reason, pure and simple, was that he spoke Japanese, and the reason for that was because his parents had worked in Japan as Mennonite missionaries. Mennonites back home, he said, had believed in his parents’ higher calling and had funded their life’s work.

His Mennonite upbringing had also helped equip him for a career in journalism, he said.

“We were taught to be in the world but not of the world, which is what a true journalist should be,” Yoder said. “A journalist is paid to be an observer, not a participant.”

And it was that perch as an observer of the west coast scene that uniquely qualified him to provide the opening commentary on the convention theme.

A lot of venture He described Silicon Valley as “possibly the capital was purest expression of the potential of free market flowing into capitalism to create innovations.” It was one windfarms of the country’s “most concentrated spots of green” with scores of to power air transformative start-ups and billions of dollars conditioners, but in venture capital being raised by idealistic comnot much going panies eager to become the green tech version of for wind energy Google. He likened the region to light a school to a “primordial pool” of engineering brilliance, in Nicaragua. teeming with thousands of start-up amoeba from which a few survived to evolve into fish, with a handful being able to crawl up on shore and become “furry mammals” that could walk.

Other countries were eager to duplicate Silicon Valley’s inventive success but many lacked what Yoder called Silicon Valley’s “big secret sauce” — a huge tolerance for risks and failure.

“Everyone likes the idea of having a hotbed of innovation in their country, but most can’t stomach the failure rate,” he said.

Despite Silicon Valley’s vaunted success and

idealism, however, little was being done to adapt new technologies to benefit the needy, Yoder said.

New Frontiers: New Solutions

Everyone wants a hotbed of innovation, but few can stomach the high failure rate

While California was a pioneer in wind technology and carbon capture, his staff of 14 business reporters were hard pressed to find examples of start-ups that were geared to serve the poor.

Upscale Californians could indulge themselves with slow food festivals and dine on sustainable fare but in depressed West Oakland there were no grocery stores for people to buy fresh produce, organic or otherwise.

A lot of money was flowing into windfarms to power air conditioners, but not much going for wind energy to light a school in Nicaragua, he said.

Silicon Valley may be brimming with venture capital, but developers of green tech in El Salvador were having trouble getting to market with low-tech, energy-efficient stoves that would have a direct and measurable impact on people’s lives.

“The capitalism that flourishes so remarkably here in Silicon Valley isn’t always good at closing those gaps,” he said.

Could green technology work for the poor and still turn a profit, he asked, or would that task have to fall to governments and non-profit organizations? “Is there a business model that can address the bottom third?”

Attenders were left with sharpened appreciation for the role of risk in business and the lingering question of how creative capitalism — either their own or the form practiced by MEDA — could continue to close the gaps Yoder outlined. As the days unfolded they would have plenty of chances to explore further frontiers ripe for action by entrepreneurial people committed to finding business solutions to poverty. ◆

New frontiers in food

photo by Ray Dirks

It looks so simple, the food on our plates. But it can be deceptively complicated, a matter of not only seed and soil but also dizzying science and frustrating economics.

How is the age-old business of nourishment a new frontier? Where, in the numbing supply of variant opinion, are workable solutions for the billion people who end each day with empty bellies?

MEDA’s San Jose convention made no attempt to pose a final strategy for how to feed a hungry world, but there was no shortage of options to consider as one traveled the paths from speeches to seminars.

Nor was there any disagreement on urgency.

“There is a war on hunger that we have an obligation to fight with all our ability,” said keynote speaker Len Today’s challenge was to double food production bePenner, who as president of Cargill Canada anchored one tween now and 2050, “and this is something we can do,” end of the spectrum of conversation. he said. “And we can do it without drawing enormous

“Tackling this challenge is not an option, it is a must,” amounts of additional land into production — provided he said. “As followers of Jesus who are taught to love we take the appropriate signals and make the appropriate God and love our neighbor, investments.” Part of the do we see the malnourished today or the growing The world was not running out of food, though there were huge issues of cost and uneven and inequitable solution — “use populations of tomorrow as our neighbor?” distribution of food, he said. “But in terms of the total products of photosynthesis available to nourish humanall the tools in Penner said his views were shaped by his long ity, we are as far from famine as we have been in human history.” the toolbox” experience at Cargill, one of the world’s agricultural Penner said 70 developing countries, many in sub-Saharan Africa, were particularly vulnerable for reasons that giants, and filtered through included inadequate storage and transportation infrastruchis faith principles — “although the two have never been ture, trade barriers, poverty and conflict. at odds.” A good deal of the solution lay in existing knowledge.

Behind Cargill’s massive web of industrial links, which “If we take the solutions that science offers and bring the included energy, financial investments and global trade, rest of the world up to the standards of modern agriwas a fundamental purpose of “nourishing people” culture, we would increase production by 80 percent,” through nature’s conversion of sunlight and carbon diox- he said. These standards included farming practices, ide into food, he said. equipment technologies, genetics and crop management

Penner said the 1980s and 1990s had seen progress practices. in reducing hunger but now the numbers of malnourished Part of the solution was “to use all the tools in the were again climbing because of dwindling global aid and tool box” to ramp up global food production, Penner said. investment in agriculture, soaring food prices, and a world These tools including genetically engineered crops that economic crisis that shriveled employment and reduced were drought and disease tolerant but which western remittances sent home by expatriates. environmental lobbies had persuaded some African gov-

As a consequence, an estimated 16,000 children died ernments to ban. By his reckoning, stronger agriculture, every day from hunger-related causes — “that’s one child food security and raising farmers’ earnings did not have to every five seconds.” conflict with environmental concerns. ◆

Len Penner: “Do we see the malnourished as our neighbors?”

Frontiers in fruit

Growers pose new solutions — compassion, servanthood and sensible immigration reform

When you hold a meeting in California you pay attention to fruit.

There was plenty of it at the San Jose convention, from walkaround snacks of organic plums to specially packed “MEDA Mix” pouches of dried fruit in everyone’s registration bag.

Seminars tackled a range of topical palates, and a hands-on cooking class gave tips on preparing prosciutto-wrapped fruit with balsamic glaze.

Saturday’s keynote address provided a powerful look at how a faith-based quadruple bottom line animated one of the most successful fruit operations in the country.

Members of the Broetje Orchards family, one of the largest apple growers in America, related how servanthood, employee care and environmental concern can rank alongside profit in bottom-line coordinates of “purpose, people, planet and profit.”

Keynoters Suzanne Broetje (daughter of the founders) and her husband Roger Bairstow said Christian values had led the Broetje family to develop compassionate policies for their 1,200

photo by Lance Johnson

Kevin Dorsing of Royal Ridge Fruits on a fraternal visit to the Broetje plant; Suzanne Broetje at right. Keynoters Suzanne Broetje and Roger Bairstow shared their vision of a “solid business model” with a fourpronged bottom line.

A chapel for Broetje employees occupies a central spot, both physically and philosophically.

employees.

Early mission trips had alerted them to the needs of Hispanic people who formed a large segment of their work force, and they made a conscious decision to build their business with keen attention to employee welfare.

Among the concerns were children who might be left unattended at home while parents worked, and older kids missing school to look after younger siblings. These issues led to a variety of “family friendly” policies, including on-site childcare, an elementary school and educational

scholarships. Other components included profit sharing (10 percent), an on-site nurse, affordable housing (140 units) and a chapel.

“Planet” considerations were defined by initiatives in food safety, water conservation and alternative energy.

The company sets aside more than half its profits for a family foundation, directed by Suzanne, which supports a variety of community and development initiatives.

Broetje and Bairstow said their company’s policies were not just a matter of doing good but could be defended as “a solid business model.”

In the seminar sessions, two seasoned fruit growers took on the thorny topic of migrant labor from the standpoint of employers who need immigrants, many of them undocumented, to prune, thin and pick their fruit.

Ted Loewen, an attorney by trade, operates Blossom Bluff Orchards, a diversified 80-acre organic “stone fruit” farm (peaches, nectarines and plums) in the San Joaquin Valley near Fresno. Kevin Dorsing, Othello, Wash., is president of Royal Ridge Fruits, which together with Dorsing Farms is one of the nation’s largest growers and processors of tart cherries and other fruits.

Both Loewen and Dorsing depend on a reliable source of seasonal labor, and the reality is that much of it is supplied by migrant workers who are willing to perform the

laborious tasks. “No one ever comes to me and asks to pick peaches,” said Loewen. “It’s hard work.” He and Dorsing presented a picture of migrant labor that many Americans don’t see, and which poses a challenge to Christian views of fairness. They presented data to show that up to 75 percent of the migrant work force is undocumented (i.e., illegal). Enforcement tends to be lax, along the lines of “don’t ask, don’t tell.” Countrywide, the number of undocumented workers is estimated at 10 to 20 million. Another 500,000 to 800,000 enter the country illegally every year, and more than a few die from poor conditions in transit. With all the risks, why do they come? Because back home in Mexico half of the population lives on less than $2 a day, the growers said. Legal entry is generally not feasible, said Dorsing, who noted there was an 18-year backlog for immigrants trying to get in by legal means. Ted Loewen and his wife, Fran, supplied The speakers cast a different all convention visitors with a “MEDA Mix” light on perceptions that illegal impouch of dried plums and nectarines. migrants are milking the system. In fact, many of them pay into government coffers but utilize few public services. Accord- ing to some reports, undocumented migrants pay $7 billion a year into Social Security that will never be drawn out. “Overall, it’s a wash,” said Loewen. “They take out no more than they put in.” As a class, they were also said to be less crime-prone than the general population, he added. “The reality is the majority of those coming in are hard-working people who want to work,” said Dorsing. Both speakers agreed that immigration reform stalled after 9/11 and all energy now was going to enforcement. For them, a “new solution” would be a workable guest-worker program. ◆

A frontier of peace

It’s almost a form of counterinsurgency — a message of peace in business garb

It was a message to warm the hearts of businessminded Mennonites who treasure their peacemaking roots.

In a stirring address to MEDA’s Annual General Meeting, Pakistan program director Helen Loftin depicted efforts to help poor women in some of the world’s most volatile regions as a Mennonite form of counterinsurgency.

“Though the intent of counterinsurgency sounds very Rambo and un-Mennonite, I would argue that this is what our work does,” she said. “This is peace-building.”

How was MEDA doing it? “With women,” Loftin said. “We have seen the direct result of strengthening economic opportunities for women.”

And now, “others are seeing it too.”

For the past six years MEDA has been engaged in a series of projects — funded by U.S. and Canadian government development agencies — to give an economic boost to thousands of homebound women entrepreneurs whose traditions do not allow them to interact with men beyond their immediate family members. The programs utilize “go-between” sales agents recruited from less restrictive social classes to link women producers to more lucrative markets in sectors like embroidery, seedlings, glass bangles and village dairy production. Providing access to new markets enables women to not only earn more money but also to gain more respect (and better treatment) in their families and communities.

“All told, we aim to reach 120,000 microentrepreneurs,” Loftin said.

Linking women, like this producer of seedlings, to new markets has a hidden ROI — more respect and better treatment.

She shared stories of a few of the women with

whom she works.

Naseem is part of the fresh milk collection project which links women milk producers to better markets through a village collection agent, and which nets them higher returns by testing for impurities and fat content. Before joining the project, Naseem often faced the agonizing decision to pull her children out of school whenever the family needed money for medicine for her ailing husband. With her increased income she no longer has to choose between her husband’s medical expenses and her children’s education.

Razia, an embroiderer, had eked out a meager living making small items worth a few dollars. On some days she and her seven children had only one meal to carry them through. Her “Business is not for husband tried to discourage her from becoming women,” the husband a sales agent for the embroidery project. “Busisaid. “You will be ness is not for women,” he said. “You will be doomed to failure.” doomed to failure.” Nonetheless, she pressed on, though at first she He was wrong. found it difficult to deal with clients and converse about pricing, color, designs or delivery. But after a few months she developed the confidence to engage directly with the buyers in the market. Her margins doubled and before long she had recruited 30 women to fulfill the expanding orders.

How did those life-by-life improvements shine a

beam of hope into a country mired in difficulty? While the immediate impact is financial, the spin-offs hold a significant peace dividend, Loftin asserted.

“We do no preaching or sermonizing of any sort. Business is our calling — and it’s all about business.”

The “return on investment,” however, “generates more confidence and entrepreneurial zeal, and more money; which generates greater family stability, which

“When women earn more money, their children — their daughters — are fed and go to school.”

their homes,” she said. “For most of the country, women are deemed no more valuable than the livestock the family owns. They are easily replaced. When food, water or medicine is scarce, men receive it first, then boys, then women, then girls. In Pakistan it is particularly true that poverty’s face is female.”

Loftin said the entire nation suffered from the continued subjugation of women. “This point alone costs the country billions and billions of rupees and is a contributor to the country’s instability and its poverty.”

generates community awareness and prosperity and strength, which generates a valuable way of life worth protecting and expanding, and which rejects destabilizing influences and instead fosters peace — this is the goal of our work.”

When women earn money and control their earnings, their health and capacPakistan’s subjugation ity grow exponentially, she continued. “Their of women has a huge children — their daughters — are fed and go to price tag — poverty school. The family assets grow, and the positive momentum inspires and and instability propels the women to do more. They gain respect in their own household, and then in the community, and it grows and grows and grows.” That peace message, cloaked in business garb, was one desperately needed by a country of 180 million people beleaguered by floods, extremism and poverty. On the Human Development Index, Loftin said, Pakistan ranks 141 out of 182 countries. More than 80 percent of the economy is in the informal sector, and 60 percent of the country’s female work force is home-based.

“Their tradition restricts their mobility — the majority of women are not allowed to interact with men beyond their immediate family members, and many never leave

Complicating efforts to alleviate poverty were

geopolitical shifts as large donor agencies revamped their development strategies.

Loftin said that in recent months she’s been asked to adjust and rework plans to fit new objectives.

At one point she was asked to shift from the economic hubs of Pakistan to “strategic” areas known to be breeding grounds for extremist views that fuel the strife seen on the daily news, only to have the message change to a “lightening up” on this geographic emphasis.

The messages, she said, are “ever-evolving and they send us new directives and project parameters almost weekly.” Amid this bombardment, “never has MEDA’s ability to adapt, adjust and yet stay zeroed in on the core work of the job-at-hand ever been so evident — and so needed.

“In the wake of the shifting political and donor winds that blow our way — of late, with gale-force ferocity — we remain focused. Despite the political storms that rage around us and threaten to pull us off course, there’s still an economic opportunity to be tapped for our target clients.

“As disconcerting as this sounds — and believe me, I have been mighty disconcerted over in Islamabad these last few months — we really have to look at this as an opportunity. Because that is what it is. We should look at this as a gift to showcase our brand of peace-making.

“We have the chance to really make a difference,” Loftin said. ◆

Financial frontiers Robust, despite economic tsunami

Despite a morbid economy, MEDA ended its 2009 fiscal year in surprisingly good shape, president Allan Sauder told the Annual General Meeting in San Jose on Nov. 7.

Like most businesses and organizations, MEDA had been jostled by financial uncertainty, but it had nonetheless also experienced robust growth as several long-awaited contracts came to fruition.

“In the end, we were grateful for very solid results,” Sauder said.

He reported that gross revenue was up 36%, continuing a steady climb that began six years ago. “Our bottom line was positive by $808,000, for which we are immensely grateful considering that contributions from MEDA members and supporters were down 15% from last year overall. Fortunately, core contributions were down only 6%, while special project funding was less than one third of last year’s total.”

Carl Hiebert photo

The most gratifying performance indicator of all — bringing hope to 2.8 million families, up 156,000 from last year.

Treasurer Tom Bishop described the financial

results as “phenomenal...particularly while an economic tsunami has been raging all around us, both domestically and worldwide. We all have felt the impact of this economic crisis but I am sure none of us have experienced this more than the poorest of the poor, whom we define as our MEDA clients.”

Bishop also assured members that MEDA’s global financial operations had been carefully monitored. “This year over 95% of the operations were subject to independent external audit and the remaining 5% of the operations were subject to our internal audit review,” he said.

Bishop said the organization’s auditors had again given MEDA “an unqualified (clean) opinion, which assures us that the audited financial statements reliably reflect the financial position of MEDA.”

Sauder said the “most gratifying” feature of the past year’s performance was that “we were able to help almost 2.8 million families to live healthier, happier lives (up 156,000 from last year) through 120 partners in 44 countries.”

He said contributed dollars from supporters were multiplied by contracts from government sources, consulting services and investment earnings to the tune of nine to one.

“Every dollar you donated was able to do the work of

$10,” Sauder said, adding that individual donations were still vitally important despite the big numbers of major contracts. “Your donations, whether they are $200 or $200,000, are the yeast that makes all of this happen.”

The multiplying effect was even more dramatic on the investment side. “MEDA’s investment equity of $4.7 million in the Sarona Risk Capital Fund was multiplied by more than $19 million of investment from our members and institutional partners such as MMA, Meritas, Mennonite Savings and Credit Union and others,” he said. “These funds allowed us to invest with partners around the world, creating total assets under management of $175 million. Our $4.7 million of investment equity was multiplied 36 times — into assets of $175 million, assets that are working to create new solutions to poverty.”

Sauder reported that the organization had entered another new frontier this year by opening MEDA Europe, based in Germany and directed by Titus Horsch. This allows MEDA to issue tax receipts for German contributions, work with Mennonite businesspeople there and develop a vision for MEDA in Europe. A number of contacts have been established with European foundations and larger businesses, and connections have been made with other European development organizations with a view to possible collaboration on project proposals to the European Commission.

He also drew attention to one of the newest MEDA frontiers — the Sarona Frontier Markets Fund. This “fund of funds” will invest with private equity fund managers around the world who have proven they can take a risk with small and medium enterprises (SMEs), get reasonable returns, and who share MEDA’s values of investing to benefit the poor.

“Just as MEDA was one of the pioneers in creating

MicroVest five years ago, and proving to Wall Street, Bay Street and Main Street that investment in microfinance can generate financial returns as well as social impact, we expect that the Sarona Frontier fund will prove that SME investments are a viable way to achieve a triple bottom line — Profit, People, and Planet,” Sauder said.

He said MEDA was this year looking for

member contributions to reach $3 million, including over $600,000 for the Sarona Risk Capital Fund. Applying the usual multiplying factors, this would allow MEDA to reach eight million families.

“These, admittedly, are very ambitious goals in a very flat global economy,” he said.

Achieving them would require not only financial support but also moral support to research new solutions to poverty and to take the risks to explore new frontiers.

“It is your example of challenging the frontiers that gives us courage to try new ideas and approaches,” Sauder said. “It is your abiding faith in our mission that gives us strength to persevere in the face of adversity. And it is your prayers that we feel when things don’t go as planned.”

It was reported to the annual meeting that Denver physician Mel Stjernholm had concluded his three-year term as MEDA chair and was succeeded by Allon Lefever, entrepreneur and former business professor in Harrisonburg, Va.

The next Business as a Calling convention will be held Nov. 4-7, 2010 in Calgary. ◆

Carl Hiebert photo

Soundbites

Why God created commerce

God did not bestow all products upon all parts of the earth, but distributed His gifts over different regions, to the end that men might cultivate a social relationship because one would have need of the help of another, and so He called commerce into being, that all men might be able to have common enjoyment of the fruits of the earth, no matter where produced. — Greek phi‑ losopher Libanius (314‑394)

Not rocket science

To make customers happy, all you need to do is offer highquality goods at competitive prices and staff your stores with a sufficient number of well-trained personnel to ensure a smooth shopping experience. Like the man said, you should make your money the old-fashioned way: by earning it. Trust me, that’s the shortest route to making your customers happy. — David Lazarus in the

Los Angeles Times

All charged up

Last year when I was in Haiti — one of the poorest, least developed countries — I learned one benefit of going to church: You could charge your phone battery under the window ledges lining the sanctuary. Come to church

Ooops. Didn’t mean for that to happen

After the genocide [in Rwanda], Jean seized an opportunity to begin a small poultry business to provide his neighborhood with eggs. He managed to scrape together funds to purchase several fowl, and his business grew. Later, a church in America “adopted” the village where Jean lived and worked. The church decided to donate clothes and supplies. They also imported eggs from a neighboring community and gave them away. Suddenly, this one village was flooded with surplus eggs. It is not difficult to imagine what happened to Jean’s business: people went first to collect free eggs and bought Jean’s eggs only when the supply of free eggs was depleted. The market price for eggs plummeted in Jean’s village and, as a result, Jean was forced to sell his productive assets, his chickens.

The next year, after Jean had left the poultry business, the church that had supplied the free eggs turned its attention to another disaster in another part of the world. Jean’s community had no capacity to produce eggs locally and was forced to import eggs from a neighboring town. The cost of these eggs was higher than the eggs Jean had sold, so both Jean and his village were hurt economically by the good intentions of one American church.

Have you ever donated your used T-shirts to your local thrift store? Often these are bundled and shipped to Africa. This business of secondhand Western clothing...decimated clothing production in countries like Uganda and Zambia that previously had thriving textile industries.... It is hard to comprehend that our used T-shirts could harm local producers on another continent, yet the American church must learn to be aware of such consequences in our increasingly interconnected world. — Peter Greer in The Poor Will Be Glad: Joining the Revolution to Lift the World Out of Poverty late, and you might not get a power outlet. — Brad Abare, founder of the Center for Church Communication, in Christianity Today

One-fifth perfect

I cringe every time I hear about people being carbon-neutral. You quickly realize how hard, if not impossible that is. You don’t need to be perfect, you just need to be 20 percent better. — California green guru Terry Tamminen in the Globe & Mail

Meeting payroll

Before I started my business, my political philosophy was that business is evil and government is good. I think I just breathed it in with the culture. Businesses, they’re selfish because they’re trying to make money.... Once you start meeting a payroll you have a little different attitude about those things. — Whole Foods founder and CEO John Mackey in The Wall Street Journal

Good old dirt

The USDA estimates that about half the fertilizer used

They are often sad stories, but honest ones, too. Like all museums, pawn shops reveal something about human ambition, how we measure our journeys with the treasure we collect along the way. The trip doesn’t always have a happy ending. — Stefany Anne Golberg in the Washington Post

each year in the United States simply replaces soil nutrients lost by topsoil erosion. This puts us in the odd position of consuming fossil fuels — geologically one of the rarest and most useful resources ever discovered — to provide a substitute for dirt — the cheapest and most widely available agricultural input imaginable. — David R. Montgomery in Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations

Pawned memories

We write our biographies with our belongings.... Pawn shops are the Smithsonians of missed dreams and second chances. Behind all the discarded things lies a trove of American stories.

Dreary & dry

Poverty is the weather in Tanzania. It is just there — there when the Africans go to sleep, and there when they wake up, there every day of their very short lives. Like the weather, poverty doesn’t change enough to be a topic of conversation. Poor just is. — Pietra Rivoli in The Travels of a T-shirt in the Global Economy

News

Look what you can do with only a hundred dollars

“I don’t want to die poor,” Sylvia Banda told herself 25 years ago.

Unlike many less-fortunate Africans, she had a decent job with a government agency in Lusaka, Zambia.

“But I had a vision,” she says today.

Banda decided to strike out on her own and open a café.

She did it with $100.

“I had every hope that I would succeed,” she told a Winnipeg audience on a recent visit to Canada.

A warehouse owner let her use some space, which she filled with supplies from her home — fridge, stove, food and cooking oil.

On the appointed day she set to work, chopping onions, garlic and tomatoes. As she began frying she got an idea. She closed the door and windows and let the fragrances build up.

“When it was filling the whole place I opened the windows and people outside smelled it. They asked, ‘Are you cooking today?’ ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘come at lunch time.’”

And they did.

“But,” she says, “I suddenly realized — I did not have any tables. I did not have any chairs.”

Thinking fast, she announced to her customers: “Welcome to my standing buffet.”

They laughed. And ate, she recalls. “Amazingly, the first meal was all sold out.”

She found a carpenter and made an offer: “Make me one chair and I’ll give you free meals. Then, make me a table. In no time I had the table and chairs.”

And thus was born a catering business which she would name Sylva Catering.

The simple beginning grew into a thriving catering operation which today has 16 cafeterias spread across the city of Lusaka. Banda also opened a guesthouse and a college that trains students in catering and hospitality.

Aided by her husband, Hector, who helps manage the 100-employee enterprise, their brand has grown to include cookbooks and Banda’s own label of indigenous foods such as dried pumpkin leaves and seeds, pounded groundnuts, and dried and fresh okra.

“We package almost all known indigenous Zambian foods and sell them in supermarkets besides putting them on our menu,” she says. “We

Stu Taylor photos

Zambian entrepreneur Sylvia Banda and husband Hector

also do exports to countries like Angola, Congo and Nigeria.”

Now Banda is planning a $5 million hotel development.

She has received numerous awards for her achievements, including being honored as

one of the six most outstanding African entrepreneurs in 2001.

She is on the boards of the Zambia Chamber of Small and Medium Scale Business Associations and the new Zambia Development Agency.

Banda admits to finding it hard to grasp her level of success, having started with almost nothing. “This tells me that money alone is not a launch-pad for success but commitment and ability driven by vision,” she says.

She also points to the importance of spiritual values,

Suddenly realizing she had no chairs, she told customers, “Welcome to my standing buffet”

Sylvia Banda: “As God-fearing people... no kickbacks.”

“Earthy but pious man” set the tone for employee care

especially in facing obstacles of corruption.

“There are times when we have failed to get business from government institutions because our competitors opted to corrupt some official,” Banda says. “But as God-fearing people, we cannot give kickbacks. In whatever we do, we always put God first and seek his guidance.”

Banda’s Winnipeg visit was sponsored by International Development Enterprises (IDE), an agency that specializes in appropriate technology such as low-cost pumps and irrigation systems for small farmers in several countries.

She has worked with IDE clients in Africa, helping the farmers to grow foods best suited to their area and training them in matters of costing and hygiene.

“We have trained more than 6,000 farmers,” she says.

charitable causes, got involved with a hospital for the poor, and founded the first Sunday schools in Ireland.

His heirs absorbed his altruistic philosophy, funded significant missionary ventures and set a new standard for the treatment of employees. The Guinness company “strove to improve the lives of its employees with the same intensity as it strove to sell its beer,” writes Mansfield.

By 1928, “not a particularly enlightened time for employee care,” Guinness employees in Dublin enjoyed round-the-clock care from doctors, dentists, nurses and home health workers, as well as pensions when they retired. Perks included savings banks, exercise facilities, reading rooms and educational benefits for both workers and their families.

Whatever one might think of the company’s product, the lasting legacy of the Guinness story, Mansfield asserts, “is that character is king, that markets without ethical boundaries make Madoffs but that corporations driven by a benevolent vision can do vast amounts of good.” ◆

Beer and revivalism aren’t often mentioned in the same breath, but they found common cause in last year’s 250th birthday of the Guinness brewing company, producer of the world’s most recognizable brand of suds. In the mid-1760s, a young Irishman by the name of Arthur Guinness fell under the influence of famed revivalist John Wesley, writes Stephen Mansfield in The Search for God and Guinness, a celebration of the Guinness legacy. Guinness, who had just begun to make a name for himself as a brewer, took to heart Wesley’s fervent preaching against self-centered living and disregard for the poor. Depicted by Mansfield as “an earthy but pious man,” Guinness parlayed his brewing success into a legacy of benevolence for the downtrodden. He generously supported