4 minute read

The power of art

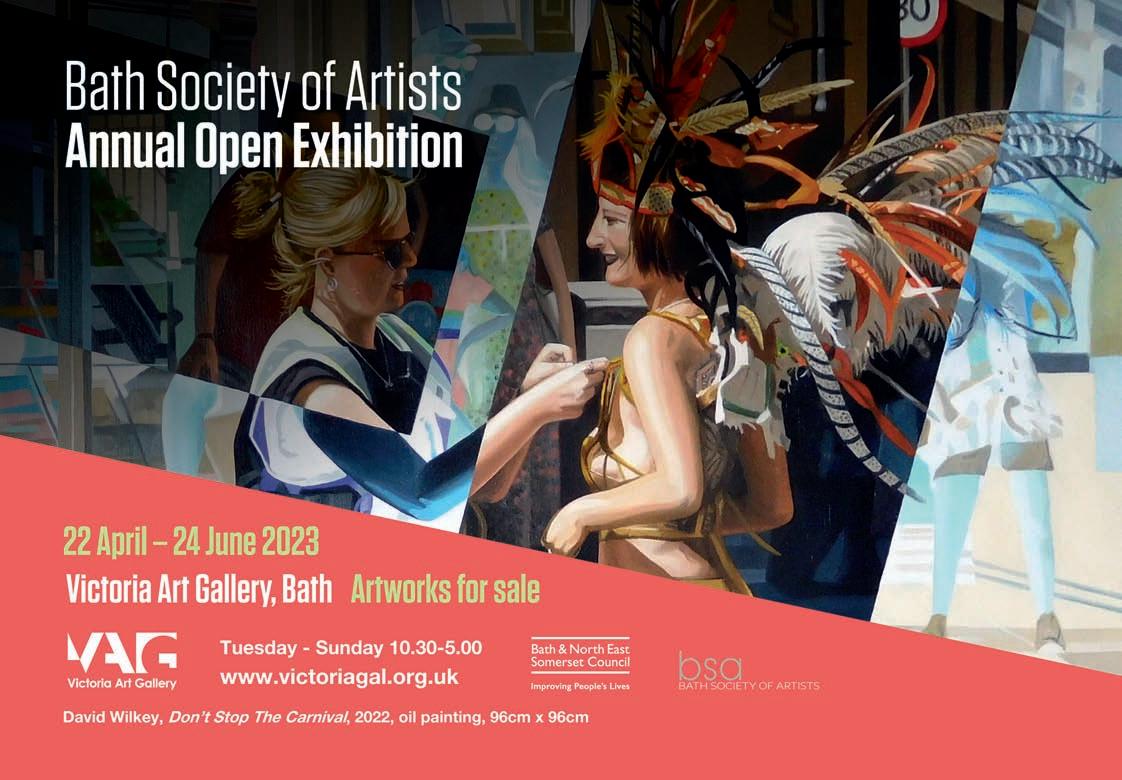

On 20 May, the RWA will welcome it’s latest exhibition – Found Cities, Lost Objects: Women in the City Here, we take a closer look at the Bristol artists included in the exhibition –all of whom are reminding us that “art is a powerful tool in shaping our cities and the world around us”...

Royal West of England Academy’s (RWA) next exhibition in its newly renovated building and main gallery space is an exciting and challenging touring exhibition curated for the Arts Council Collection by Turner Prize-winning artist and cultural activist Lubaina Himid CBE.

Advertisement

Found Cities, Lost Objects explores modern city life from a female perspective and encourages visitors to view the city through a woman’s eyes. The exhibition addresses themes ranging from safety and navigation to concepts of belonging and power. From billboards and advertising posters to public statues and monuments, cities today are saturated with idealised images of women. Together, these depictions communicate subconscious messages about how women are valued, whether they are welcome, and how safe they might feel.

In Found Cities, Lost Objects, Himid brings together a group of over 60 works that address these themes, questioning our understanding of the urban environment and encouraging a rediscovery and reclaiming of our cities. Some of the artists featured from the Arts Council Collection include Lisa Milroy, Tai Shani, Magda Stawarska-Beavan, Mona Hatoum, Cornelia Parker, susan pui san lok and Helen Cammock.

Reclaiming of the city while holding a mirror up to its history is a theme that is explored in the work of some of the five Bristol artists included within the exhibition: Valda Jackson, Mellony Taper, Beth Carter, Huma Mulji, and Veronica Vickery.

Valda Jackson’s Still Holding On was made originally for a billboard in 2017 and has been specially reworked for this exhibition. The work will form a centre piece for the exhibition, covering the entire back wall in the RWA’s main gallery space. This significant work is constructed from images created over decades from photographs. The figures represent children whose parents came to Britain from the Caribbean and it draws attention to the sacrifices made by their parents who came here at the British government’s request in the drive to rebuild post-war Britain. Many of these people who are part of what is now known as the Windrush Generation came to Bristol. They worked long hours often doing heavy industrial work, eventually sending for their children and continuing to send money home to relatives. Their important role in British society has only very recently come to public attention.

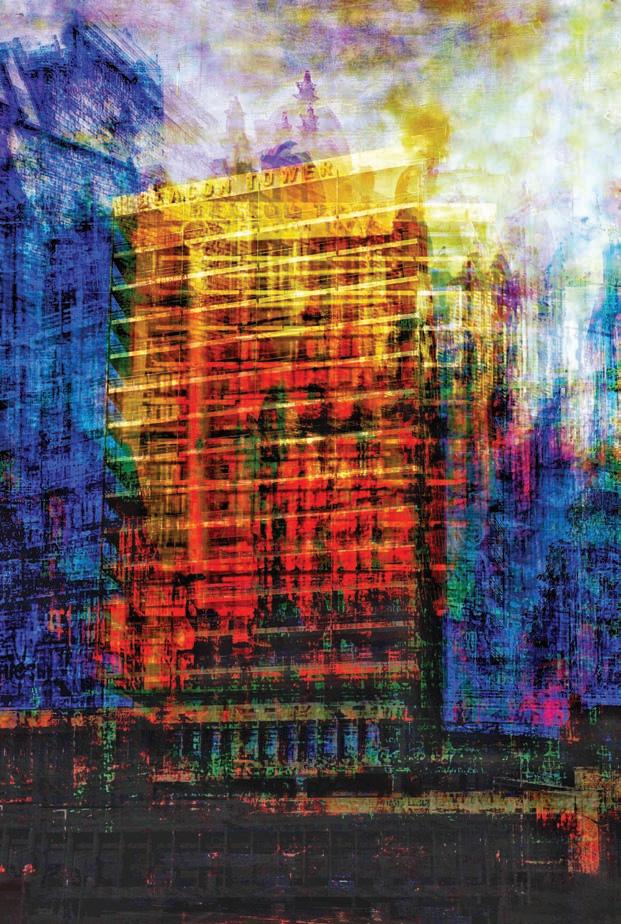

Mellony Taper’s Renamed City has its origins in the Colston protests of 2020 that changed Bristol and rewrote history. It references the renaming of Colston Hall as the Bristol Beacon.

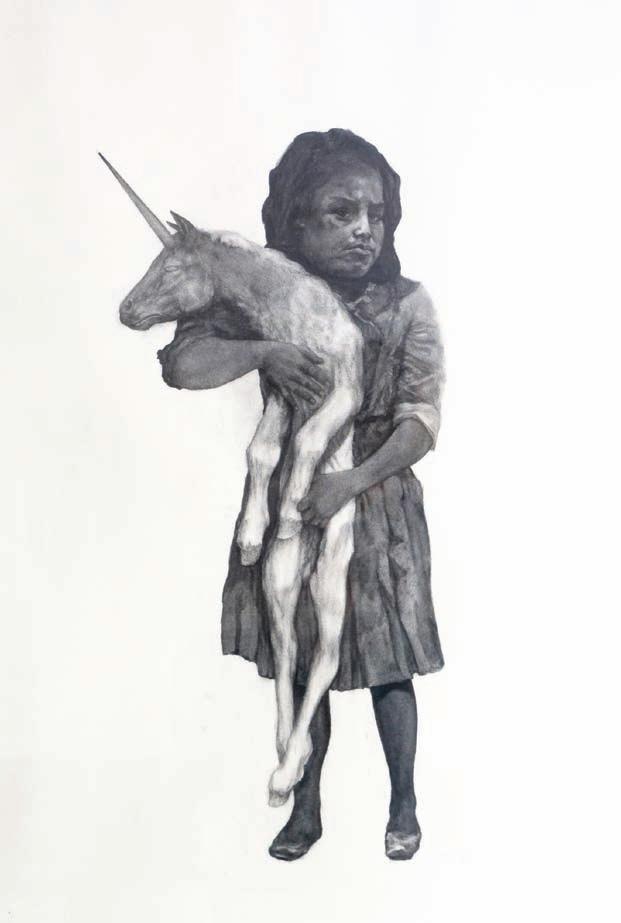

Beth Carter’s drawing Stealing the Unicorn references the significance of unicorns to the city of Bristol. They first appeared on the city seal in 1569 and were chosen to represent virtue on Bristol’s coat of arms. She said: “I have lived in Bristol for almost 25 years which, like most cities, is a layered complicated place. I’ve always loved the city’s mix of culture, history and architecture. It has a particular jumble of soulful, historic buildings butted right up next to modern and contemporary structures –the extraordinary and the mundane, ancient and new –many coexisting dualities within which, just beneath the surface, are symbols of magic interwoven through the city, in particular –unicorns. They appear on Bristol’s coat of arms, on bridges and ships.

“In my drawing, the unicorn is being stolen by a young girl. The unicorn is something precious, elusive and rare, she is stealing back something which has been lost, an act of reclaiming that holds a personal power and potency.”

Huma Mulji’s An Unquiet Grave is a suite of four photographs of meticulously preserved documents for the Bristol archives of planning permissions and building records. They refer to a port city built largely on the back of the booming slave trade, which was the source of Bristol’s dazzling wealth for over 200 years. As with Valda’s work, this information was withheld from the country’s collective memory and history curriculum, and only very recently are these issues beginning to be addressed in contemporary media.

Veronica Vickery’s installation flags up Bristol’s urban waterways, which are as much a part of the urban as the road system and the detritus in them is a product of city life. Women in particular can feel a sense of alienation in this part of the city, particularly at night, and the found objects are indicative of that.

Lubaina Himid CBE, artist, says: “Found Cities, Lost Objects challenges the status quo by encouraging viewers to discover the city through the eyes of female artists. Women generally inhabit cities via retail and healthcare venues, but how can we expand our presence beyond this for everyone’s benefit, now that these spaces are under pressure to perform differently? The exhibition explores the contradictory experiences of women across the city, free to roam the streets while always considering the boundaries within which that freedom is contained.”

Alison Bevan, RWA Director, said: “We’re delighted to be hosting this fascinating and timely exhibition. As Bristol celebrates its 650th anniversary, we feel it is hugely appropriate for us – as an organisation that has pioneered gender equality for nearly 180 years – should explore and honour the place of women in this historic city. We’re particularly excited to include a glimpse into the wealth of talent in Bristol through the inclusion of work by five outstanding women artists, and that we will also soon be announcing some special commissions for work to be shown on billboards across the city.”

Deborah Smith, Director at Arts Council Collection, says: “It’s always exciting to see what fresh perspective artists will bring and what stories they will tell when we give artists an open brief to curate the Arts Council Collection. The Collection has enjoyed a long relationship with Lubaina, from acquiring her work in 1988 to her show Meticulous Observations at the Walker Gallery, Liverpool, where she mined the depths of the Collection. Found Cities, Lost Objects’ impressive pedigree of female artists offers new perspectives on urban life and helps us understand how art is a powerful tool in shaping our cities and the world around us.” n

• Found Cities, Lost Objects: Women in the City is showing at the RWA from 20 May –13 August; rwa.org.uk