5 minute read

STOLL FAMILY KEEPS SORGHUM MAKIN' TRADITION ALIVE

Stoll family members squeeze the sorghum stalks in the field and the raw juice is pumped into a tank on a pickup truck. The tank holds 200 gallons of raw juice.

Folks who live or travel around the small town of Finger in northern McNairy County know when they see the Stoll family out in the fields cutting down sorghum cane, Autumn has officially arrived.

Advertisement

Many also start making plans to buy a jug or two of the sweet old Southern staple, pure sorghum molasses.

Steve Stoll’s sorghum mill is part of a family farming operation that grows garden plants in the spring, watermelons and cantaloupes in the summer, and old fashioned sorghum syrup in the fall. His three sons, Kenny, 23, Duane, 21 and Keith, 16 and 16-year-old nephews, Matthew and Mason, work alongside him helping to bring the harvest in. The McNairy County farmer learned how to grow the ancient grain from his own father, the late Victor Stoll, who as a kid helped his father grow sorghum in Arkansas.

Though sorghum is actually a type of grass, it closely resembles corn with broad leaves. Instead of tassels it has a cluster of seeds at the top of the plant. Considered a mostly drought tolerant plant. It still takes a lot of management for quality food-grade sorghum.

As with other crops, the weather often determines how much a sorghum crop will yield. This year, there was a long dry spell during the late summer. Sorghum farmers also had to scout for and control sugarcane aphids that in recent years have been destroying stalks.

Stoll, who planted his sorghum crop in May, harvested for two weeks in October.

“We are running a little late this year so we’ll be harvesting until the weather ‘freezes’ us out,” he said.

To make the syrup, the sorghum is cut and the seed heads removed, then “pressed” in the field to extract all of the juice out of the stalks.

If a storm comes through and blows any of the stalks down, they are hand-cut. Within a couple of hours of extraction, two hundred gallons of juice is transported back to the mill where it is cooked.

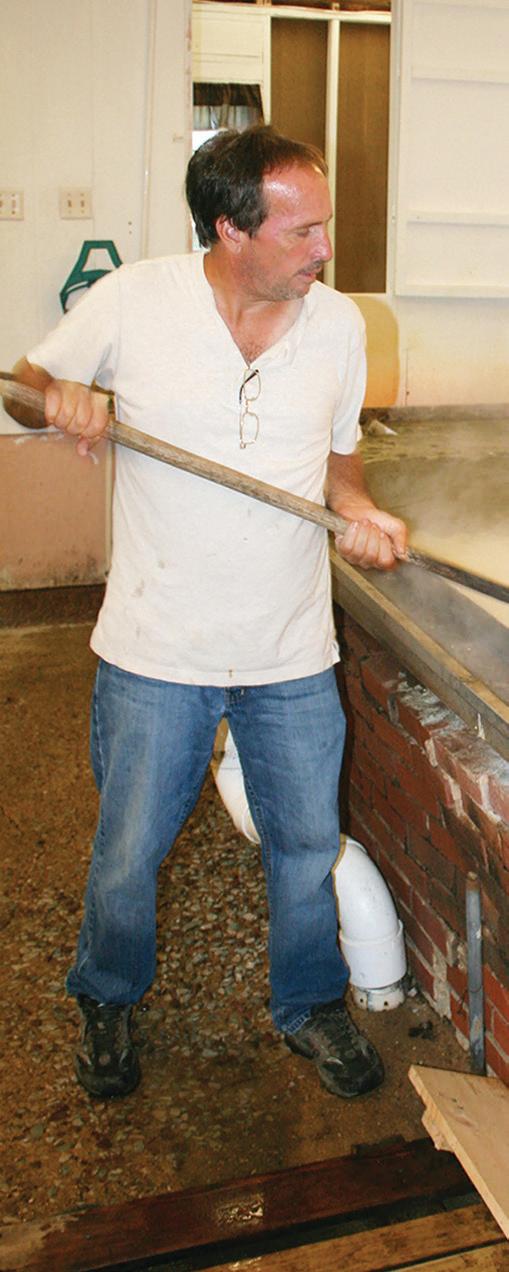

“Cooking the syrup is an all day process,” said Stoll. “My sons and nephews extract the juice all day and I cook it all day until I have a finished product. It’s a continuous flow of green juice coming in and product coming out.”

His expertise after years of cooking the sweet, earthy sweetener lets him know when it’s the perfect consistency. He also judges for its color, sweetness, clarity and flavor.

The business man said his mill will make a little under 4,000 gallons this season, but use to make as much as 11,000 gallons when he had a bigger operation. The finished product, sorghum “molasses” is “pure” with nothing added and is sold in pints, quarts and gallons throughout the area, including Roger’s and Gardner’s in Corinth. He also sells it all over the state of Tennessee, northern Mississippi, Alabama, Missouri and even Texas. The syrup can also be picked up at his mill on Sweet Lips Road near Finger.

Before it became mainly a family operation, Stoll said they would cook up 500-600 gallons of product per day at the mill but now they did more like 200 gallons of finished product a day. His wife, Linda, helps during the entire sorghum making process.

“Without her, we couldn’t run this operation. She’s the anchor,” said the farmer.

Besides their three sons, the couple have a 12-year-old daughter, Amy. Stoll noted both his wife and mother eat sorghum molasses every day. Not indigenous to the United States, sorghum plants were imported from Africa in the mid-1800s as a cheaper and more accessible sweetener. Though considered a Southern tradition and practically synonymous with hot biscuits and butter, the syrup was even more commonly produced in Mid-Western states in the late 1800s.

Sorghum is also an ancient grain. Thousands of years ago, it was eaten by ancient Egyptians and for centuries has been a staple food for a large portion of the populace in Africa and South Asia. Today, it feeds more than 500 million people in more than 30 countries and is the world’s fifth major crop.

“There are a wide range of ways sorghum molasses can be used in cooking and it is a very healthy product, except for diabetics because of its high sugar content,” said Stoll. “It is all natural – we add nothing to it. It’s just plain juice cooked down to a sticky syrup.”

“Though its hearsay, I’ve been told in the old days, doctors used it for medicinal purposes,” he added.

Sorghum-based foods, teas, beers and extracts are still used in traditional medicine in West Africa. Medieval Islamic tests also listed medical uses for the plant.

According to a study published in the “Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,” sorghum syrup “has high nutritional value with high levels of unsaturated fats, proteins, fiber and minerals like phosphorus, potassium, calcium and iron. It also has more antioxidants than blueberries and pomegranates.”

American chefs are definitely taking notice of the syrup’s health benefits, calling it the “wonder grain.” It’s being used to drizzle over salads, risottos and especially, in baking.

The dark caramel syrup has a flavor that is uniquely its own. For many Southerners, its sweet, slightly bitter flavor brings up memories of generations past. Considering “everything old is new again,” sorghum’s long endurance has proven to be a valuable food source.

Which is good news for Stoll’s Sorghum Mill and sorghum molasses’ lovers everywhere.

(This story, compiled by freelance writer Carol Humphreys, first appeared in the Daily Corinthian and Pickwick Profiles. It is being reprinted with permission. Photos by Mark Boehler / Daily Corinthian.)

Steve Stoll cooks the sorghum in the shed on his farm.

Steam rises from the sorghum cooking at Stoll’s Sorghum Mill.