8 minute read

Summer Reading |What books did Roxbury Latin’s faculty and staff read—for pleasure!—over the summer? (And why should you read them, too?)

Summer Reading

Interior Chinatown

Advertisement

by Charles Yu

Recommended by Sarah Demers, English Department

Interior Chinatown is a novel written much like a screenplay. The protagonist, Willis Wu, is an actor navigating Hollywood and the problematic stereotypes and tropes Hollywood perpetuates as he plays “Generic Asian Man” on a generic procedural cop show. With humor, wit, and soulfulness, Wu brings us into his world just outside of the spotlight as he tries to negotiate his family’s history, their legacy, and his own path forward in modern America.

Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art

by James Nestor

Recommended by Erin Berg, Director of External Relations

In a succinct, energetic way, Breath takes the reader through a fascinating biological and sociological evolution of how we breathe today, and why, and what it’s doing to our physical and mental health. What it reveals is mind-blowing, funny, scary, and enlightening. It will make you aware of your own breathing practices in ways you’ve never been before. It should be mandatory reading for every breathing human!

Hollywood Park

by Mikel Jollett

Recommended by Keri Maguire, School Nurse

Both heartbreaking and heartwarming, this beautifully written memoir was hard for me to put down. It is a story of perseverance and redemption, but mostly it’s a story of loving those closest to us for who they are. I hesitate to say more, as learning Mikel’s story through the book was part of the joy for me, but prepare to be moved!

Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging

by Sebastian Junger

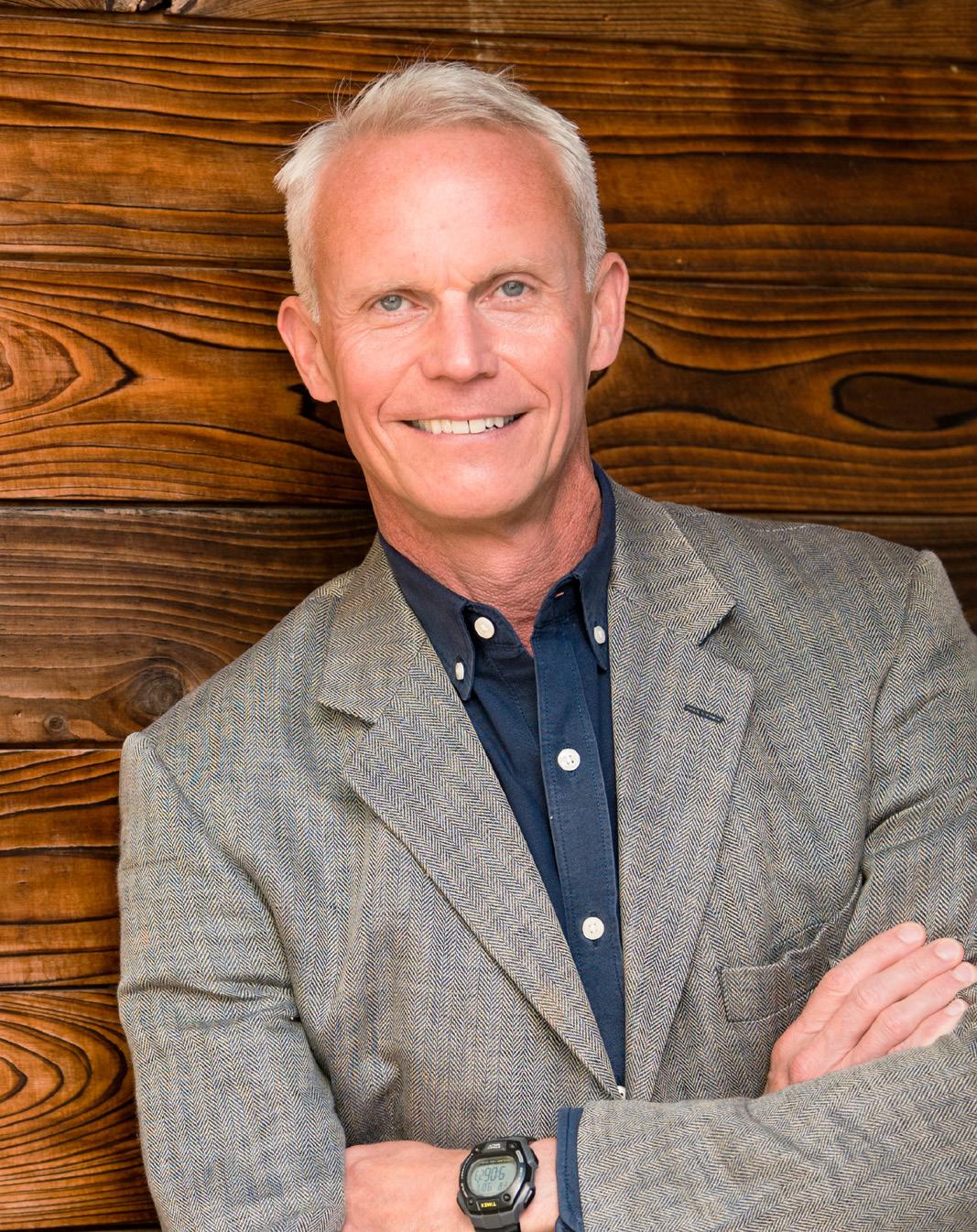

Recommended by Stewart Thomsen, History Department Chair

If you are looking for an evolutionary perspective on PTSD and a better understanding of the challenges veterans face in transitioning back to civilian life, Sebastian Junger’s Tribe may be the book for you. Why do people long for the human connection they felt with other people during catastrophic events of their past? What is it like for a veteran to feel these intense social bonds in wartime and return home where so many citizens express contempt for their fellow citizens? As Junger puts it, “The beauty and the tragedy of the modern world is that it eliminates many situations that require people to demonstrate a commitment to the collective good.” He believes the antidote for the ills of our time lies in understanding the relationship between sacrifice and belonging, and he believes that earlier human societies have valuable lessons for us in the present.

by Madeline Miller

Recommended by Mo Randall, English and Classics Departments

Not an original observation, but Madeline

Miller’s novel Circe is the best book I have read in the last several years (All The Light We Cannot See is in the same category). She re-imagines story lines from mythology and the Odyssey with brilliance and an almost studied nonchalance. She gets the voice and the main character spot-on. It is a work that makes you rethink what you know and, basically, it just makes you think and feel.

This is Your Mind on Plants

by Michael Pollan

Recommended by Sean Spellman ’08, Assistant Athletic Director

In This is Your Mind on Plants, Michael Pollan explores three different plant drugs and the cultural, physical, and psychoactive effects they’ve had on humans—both individually and culturally. The book is an easy read that is at once historical research, scientific analysis, and memoir. I particularly enjoyed his analysis of caffeine, which led me to reevaluate my daily need for a fix of cold brew at El Recreo on Centre Street!

Journey to the Edge of Reason: The Life of Kurt Gödel

by Stephen Budiansky

Recommended by Daniel Bettendorf, Mathematics Department

Unquestionably the most important mathematician of the twentieth century, Kurt Gödel did work in logic that struck a blow to mathematical formalism and cast serious doubt on the ability of any computer to reproduce the thinking of the human mind. This new biography puts his accomplishments in their proper historical context, while also covering the personal journey of this brilliant, quirky, Austrian emigré and friend to Albert Einstein. (Einstein did not much care for long walks, unless they were with Gödel.) As a bonus, an appendix succinctly outlines the proof strategy of his mind-blowing Incompleteness Theorem.

Three Important Voices (in Three Books)

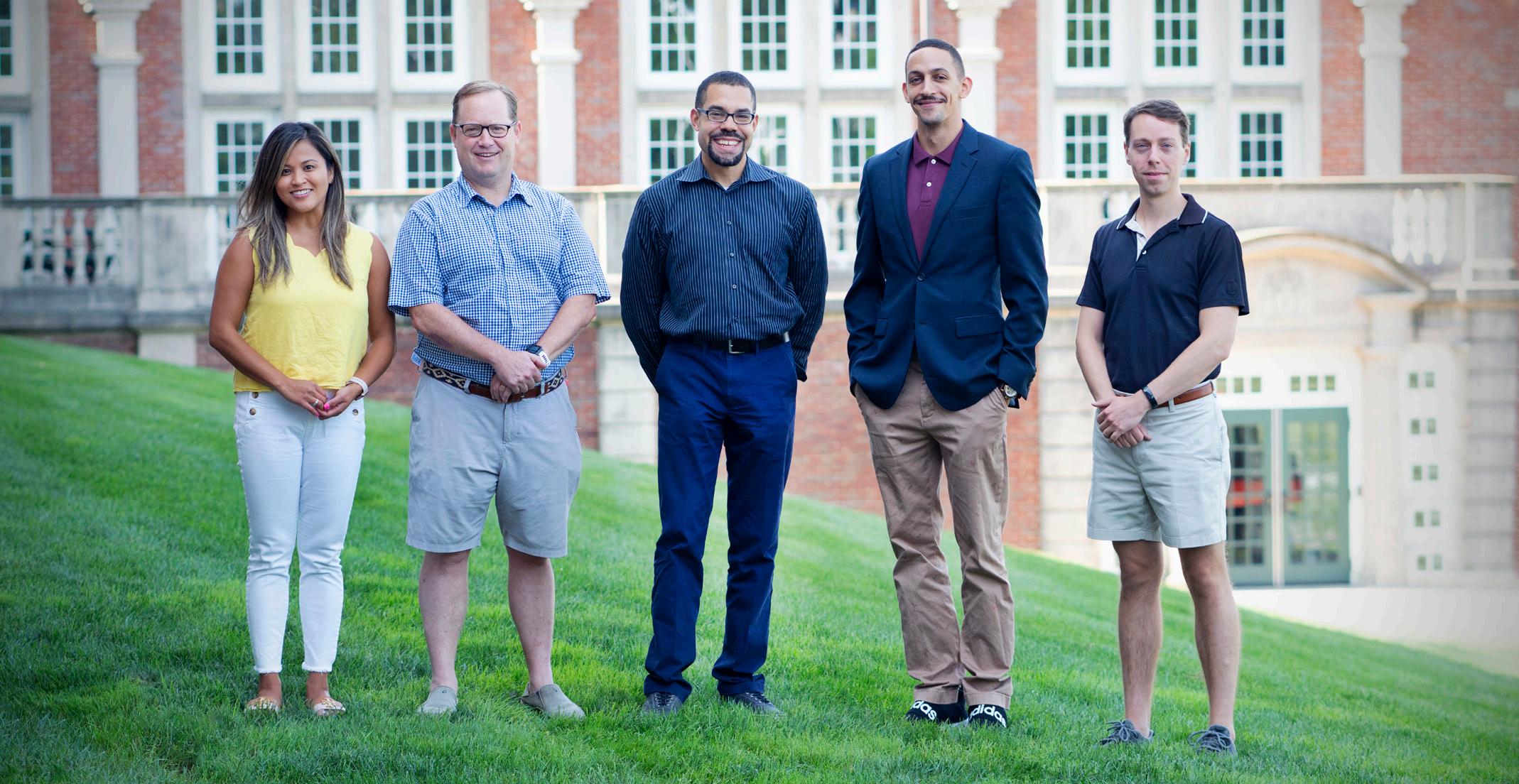

Recommended by Josh Cervas, English Department Chair (When you’re head of the English Department, you get three recommendations!)

Something to Declare

by Julia Alvarez

Alvarez’s 2014 collection of personal essays traces her early life in the Dominican Republic and her family’s flight from Trujillo’s dictatorship to New York, where they settle and grow into their new country and culture—a series of scenes that radiate warmth and possibility, while also observing the complex personal challenges of growing up and fitting in. The book’s second half turns to a different kind of arriving—Alvarez’s emergence as a lover of language, teacher, and writer (she eventually lands right here in New England), a thankful outcome given these open-hearted essays alone.

Hamnet

by Maggie O’Farrell

Set in England during the plague year of 1596, and centered on the illness and passing of Shakespeare and

Anne Hathaway’s only son, Hamnet (the book’s name and the boy’s) is a beautiful work of historical fiction—a stirring, richly imagined story about loss and the daily work of enduring. Hathaway, called Agnes (pronounced Ann-yis), rather than Anne, emerges as the center of the book’s teeming, fraught world—wife, mother, healer, seer, a product and prodigy of nature, a figure as recognizably human as she is wholly original. Though Shakespeare goes unnamed throughout, there are plenty of sugar highs for those who love the bard, the final scene— when Agnes, full of grief and accusation, takes to London to find her husband amid his work and life apart—a particular rush. But the novel’s world, beautiful and pock-marked both, is thankfully much broader than that, and it’s all worth reading.

The Fire Next Time

by James Baldwin

If Alvarez’s collection of essays is warmth, Baldwin’s seminal two-essay pairing The Fire Next Time is, as the title makes plain, fire—vital, insistent, and morally fueled. Among many other things, “Letter from a Region in My Mind” is a revelation of many modes—of Baldwin’s crisis of faith and family, of the hardships and humiliations of his circumscribed world, of his growth into consciousness, of the limitlessness of American racism and beauty destroyed, and of an essential route forward: embracing, not avoiding, the fact of human mortality and deciding “to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life,” for the sake of those that come after us. Though less heralded, the collection’s first essay, “My Dungeon Shook,” a letter from Baldwin to his namesake teenage nephew, burns with urgency, too.

Shuggie Bain

by Douglas Stuart

Recommended by Derek Nelson, Director of Dramatics; English Department

Most reviews of Shuggie Bain used the word “heart-rending”—and it is. The novel starts with the teenage Shuggie, now living on his own in a dingy flat in Glasgow, having accepted that he’s gay and that he can’t save his mother, Agnes, from her demons—drink, drugs, sleeping with anyone and everyone. He’s looking back at his younger years trying to survive with his mother and “Big” Shug, his father, a taxi-driver, a philanderer, and a bully. She’s Catholic; he’s Protestant—they’ve crossed that fault-line. She’s spiraling downwards, clutching at men, and making young Shuggie responsible for her. The book’s full of lyrical passages about the “estates” (tenements) in Glasgow, hardscrabble lives, the brutality of Thatcher’s austerity measures. It’s the beauty of the writing about coming-of-age that lifts it out of just being gritty. It reminded me in places of Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, by Roddy Doyle and Black Swan Green, by Stephen Mitchell. We see the world through Shuggie’s eyes.

Homeland Elegies

by Ayad Akhtar

Recommended by Andrés Wilson, English Department

Ayad Akhtar's Homeland Elegies is an experiment in autofiction that pays tribute to the author's complicated relationship with his Pakistani-born parents—especially to his father, a conservative-leaning medical doctor who achieved some semblance of the American dream. However, the book also offers a poignant meditation on the various interstices of American experience. Eschewing easy answers and subverting generalizations, Akhtar’s book lays bare the burdens and blessings of being the child of Muslim immigrants before and after 9/11. In today’s divisive political climate, I appreciated reading a nuanced, self-aware, and sincere voice of cautious patriotism.

The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero

by Larry Sloman and William Kalush

Recommended by Jim Ryan, Modern Languages and Arts Departments

My father—a professional magician for over 50 years—is a former president of Boston’s chapter of the Society of American Magicians, which was founded by Harry Houdini. Dad always talks about Houdini, so I had long since wanted to read a biography of the man. What stayed with me from this book was Houdini’s pronounced devotion to his family as well as his rich connection to Boston. I was amazed to learn that he worked as an agent of the U.S. Secret Service in Europe around the time of World War I. Houdini also helped to train U.S. soldiers going to Europe on how to escape handcuffs and jail cells in the event that they were caught. Kalush and Sloman present an incredibly engaging, and marvelously researched, chronicle of Houdini’s life. //

On September 24, students in Dr. Sue McCrory’s AP Art History class were treated to a special visit at the McMullen Museum at Boston College, where they received a private tour of the Mariano exhibit by former RL parent and Professor of Romance Languages and Literature, Elizabeth Goizueta. Mariano was a 20th century Cuban Surrealist painter, and the exhibit at BC is his first retrospective featuring more than 140 paintings. >>