6 minute read

Lunch in the Pisgah Wilderness

Century-old survey notes reveal amusing anecdotes

STORY AND PHOTOS BY MARSHALL HUDSON

I’m reading the surveyor’s field notes from the 1915 official town line perambulation for the town of Winchester. It reads as though the perambulators were having quite an adventure, and I’m wishing I had been there with them.

The participating towns were taking turns providing lunch for the crew, and on the final day, it was Winchester’s turn. Selectman Walter Sawyer broke into his knapsack and produced crusty thick bread sandwiches full of flavorful meat, wrapped in wax paper, which he passed around to the rest of the team. He also shared blocks of sharp cheese, pucker-up pickles, doughnuts and a thermos of not-so-hot coffee. Except for the coffee, everything was homemade, delicious, and the hungry perambulators chowed down on it.

Winchester is in the southwestern corner of New Hampshire and bounded by Hins- dale, Chesterfield, Swanzey and Richmond. To the south, it is bounded by Warwick and Northfield, Massachusetts. New Hampshire law requires that selectmen of abutting towns jointly walk, or “perambulate” their common boundary once every seven years and renew or replace any missing boundary markers.

This 1915 perambulation team was fulfilling that statutory obligation. Along with the selectmen of the various towns, there was also a young surveyor named Prentiss Taylor with the work party. Taylor was 25 years old and recently graduated as an engineer from Tufts University. Armed with a staff compass, he was responsible for keeping the crew plunging straight ahead along the invisible town line through the dense woods, up the steep hills, across the mucky swamps and through the isolated terrain of the Pisgah wilderness. Taylor also penned the quirky comments I’m now reading almost 110 years later.

Taylor not only kept track of the compass bearings and number of feet surveyed each day, he also recorded the names of the individuals present and anything unusual that happened or that he found amusing. On the second day, Taylor wrote, “Selectman Walter Sawyer came prepared for all emergencies. Strapped to his belt were a woodsman’s hatchet and a 38-caliber revolver. While replacing a marker south of Fullam’s Pond a shot sounded. On investigating, I found Sawyer holding a huge porcupine on a crotched stick. Bounties were paid on these animals, and to collect the fee it was required to show the nose of the carcass. Walt declared, ‘I want to show the size of this kill and carried it home.’”

On day three of the adventure while in the dense woods of Pisgah on the Chesterfield-Winchester line, Taylor writes, “Selectman Reed expressed a strong and greatly concerned opinion that we were off course and lost. I checked the compass heading, and it appeared correct. The Winchester Selectman persisted and proceeded to climb the tallest tree to prove his location. From that vantage point he shouted down,

‘I can see Mount Monadnock,’ which proved nothing but did satisfy his anxiety. A few days later, on the Richmond-Winchester line, we were having difficulty locating a marker. Walt Sawyer, another Winchester selectman, said, ‘No problem, Reed will climb a tree and look at Mount Monadnock and then all will be well.’”

It wasn’t just the Winchester selectman that Taylor found amusing. He records that a Chesterfield selectman named Albert Post was so “allergic” to snakes, that he wouldn’t venture into the Pisgah Wilderness and instead sent his brother Harold to represent him. Harold was a hardy outdoorsman and not allergic to snakes, but he was allergic to certain people. At the end of a long hard day of brush-busting and trekking many rough miles, the perambulation party emerged from the woods onto a road and were delighted to be offered a ride by a man named Qualters. Harold Post was “allergic” to Qualters and preferred to walk back alone in the dark, through the wilderness, rather than ride with him. Post turned and went back the way he had just come without discussion or saying goodbye.

A Hinsdale selectman named Stearns also earned a mention in the surveyor’s field notes. Stearns was reconnoitering the line north of Kilburn Pond ahead of the main party who were working their way toward him. In a dry matter-of-fact manner, Taylor writes, “A loud shout for help rang out. We rushed forward and found Stearns waist deep in Baker-Hubbard swamp. With the combined effort of all and the help of a fallen tree after great exertion we managed to lift the two hundred-forty-pound Stearns onto dry land.”

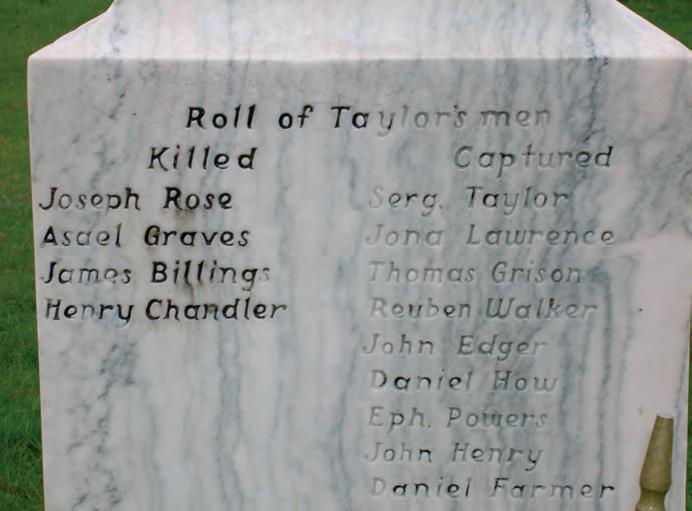

Prentiss Taylor may have had a unique inherited gene in his DNA that enabled him to lead this team through the swamps and unbroken woods. Taylor’s sixth great-grandfather, Thomas Taylor, was a sergeant at Col. Ebenezer Hinsdale’s fort when the township of Hinsdale was first being settled by English colonists. In 1748 during the French and Indian War, Sgt. Tom Taylor was leading a patrol of 16 soldiers when they were ambushed and attacked by over 100 French and Native American foes. In the running battle that ensued, four of Taylor’s men were killed, two escaped to the Connecticut River and swam across to Fort Dummer (Brattleboro, Vermont), two made it back to Fort Hinsdale, and, nine including Sgt. Taylor, were captured and taken to Canada to be sold to the French or ransomed back to the family. After being held prisoner in Canada for almost two months, Sgt. Taylor escaped and made his way back to Hinsdale. In 1871, a monument was erected at the site of this ambush, and on it are the names of those killed and captured.

A final amusing incident is recorded on the last day of the perambulation as the men were finishing their lunches. Taylor writes, “I finished the repast of sandwiches Walt Sawyer kindly offered from his knapsack. I thanked Walt and praised the good flavor. ‘Yep,’ he replied, ‘porcupine is good eating. That was the one we shot at Fullam’s Pond on the second day.’”

Hmmm...I’m still thinking I would have liked to have been with them on this adventure, but I’d be packing my own lunch.