6 minute read

Lost in History

Ever heard of Armenia White? Most people haven’t.

by Barbara Coles

It’s the perfect time — the 100th anniversary of women getting the right to vote — to give Armenia White some high-fives, though she wouldn’t have known what a high-five is. She was born more than 200 years ago, in 1817.

In her lifetime, spent mostly in Concord, White would become a pioneer of t he suffrage movement in New Hampshire and an influential member of the n ational suffrage movement, working closely with movers and shakers like Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone.

White was part of society’s elite, a May flower descendent, the wife of a prosperous Concord businessman. She and her h usband Nathaniel were active in a wide range of philanthropic and social causes, including abolition and temperance.

Armenia White

When the long-smoldering suffrage movement ignited in the 1860s, the two took up the cause enthusiastically. They would fight in the spirit of the declara tion issued by suffragists in Seneca Falls, N ew York, some 20 years earlier: “We are assembled to protest against a form of government, existing without the consent of the governed — to declare our right to be free as man is free.”

The Whites cofounded the New Hamp shire Woman’s Suffrage Association, its f ormal creation coming at a convention held in Concord in December 1868. Armenia White was elected president, a post she would hold for the next 27 years. Interestingly, among those voting, and working for the cause, were many men. In fact, a surprising number of men would offer strong support throughout the movement.

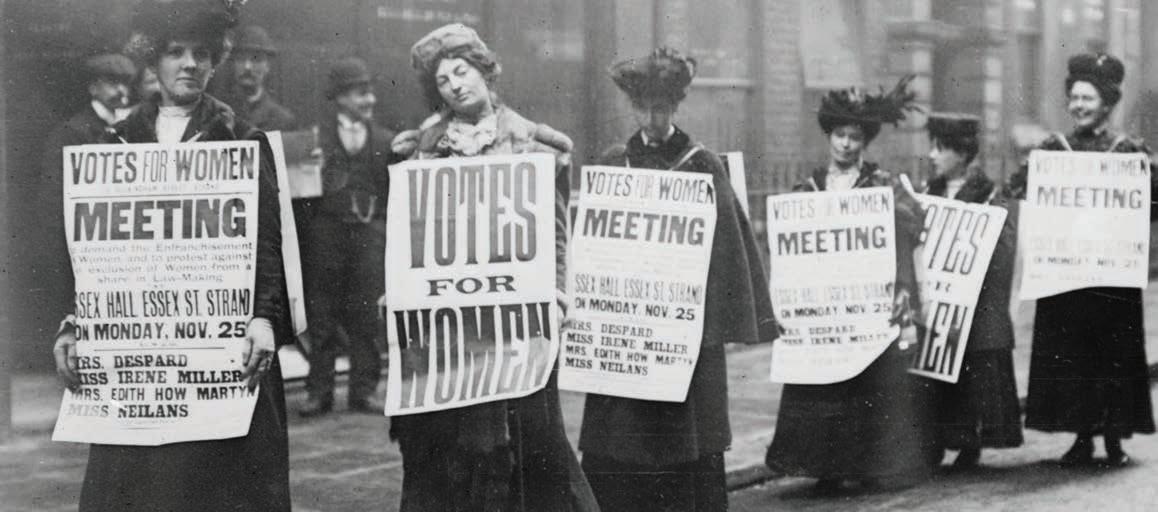

Organized efforts to oppose women’s suffrage included many women.

“What made those men so socially aware and so willing to put themselves out there for the cause of women? I don’t know, but I’m impressed,” says Liz Ten tarelli, president of the League of Women V oters, an organization that grew out of the suffrage movement.

An account of the 1868 convention in the Boston Daily Advertiser reported that its next step after the convention would be: “Agitation,’ our women’s rights friends say. ‘In less than five years women will vote in New Hampshire,’ was the decla ration of a politician usually accounted s hrewd. But will they?”

The shrewd politician was dead wrong about women voting in “less than five years” — it would be another 42 years — but the reporting was right about the “agitation.” As Susan B. Anthony said about suffrage organizations: “This society has been unrelenting in its efforts to rouse popular thought, holding annual conventions, scattering tracts, rolling up petitions, and addressing legislatures.”

One of the eight resolutions the Concord convention adopted that day in 1868 in support of women’s right to vote was: “... that the republican party having enfranchised the emancipated slaves, cannot reasonably deny enfranchisement to enslaved women.” Three years earlier, the 15th amendment to the Constitution had been approved. It gave freed male slaves the right to vote, but not women.

To “rouse popular thought,” suffragists demonstrated, circulated petitions, addressed legislatures and held annual conventions.

That amendment caused a yearslong split in the suffrage movement. Tentarelli says, “Some had opposed the amend ment, saying, ‘Let both women and f ormer slaves vote — or nothing.’ The other side said, ‘We just got through the abolition movement and the Civil War, let’s at least get the vote for former slaves. We’ll fight for ours later.’” Two competing women’s suffrage organizations formed because of the dispute; they would not come together again until 1890.

Ten years after the Concord conven tion, in 1878, the 19th amendment giving w omen the right to vote was finally introduced in Congress. To no avail — attempts to approve it were repeatedly defeated.

But there was some good news for women in New Hampshire that same year. The Legislature had voted to allow women to vote in school elections. That in hand, Armenia White and her orga nization began to work for the vote in m unicipal elections. Years into the fight, in 1889, she wrote a letter to the Legis lature that said, in part: “We are anxious t hat our petition should be granted. New Hampshire women are interested as fully as men are in the welfare of the cities and towns, and they pay their full share of the taxes. Why should we not have a vote on questions that concern us so much?” Again, to no avail — the bill was defeated.

The state’s suffragists were swimming against a tide of opposition. One oppo nent was New Hampshire luminary Sarah J osepha Hale. As editor of the then-influential “Godey’s Lady’s Book,” she helped t o promote what Tentarelli calls a “cult of domesticity,” where women are to be “pure and pious and morally superior to men, and in order to preserve that, she should not involve herself in the sordid world of politics.” (There is a bit of irony here: Hale spent three decades lobbying state and federal officials in an ultimately successful effort to make Thanksgiving a fixed national holiday.)

Opposition to suffrage was later for malized in the state with the formation of t he NH Association Opposed to Further Suffrage for Women. In “A Word to the Wise,” a credo published in 1913, it stated an overwhelming majority of women oppose woman suffrage “because it is contrary to the universal law of ‘Divi sion of Labor’ in that it belittles women’s d uties and responsibilities, making her efforts a duplication of man’s, rather than supplementary ... as nature decrees.”

In 1916, Armenia White died at age 98, her lifelong dream yet unfulfilled. Her obituary in The Granite Monthly said this: “The last of all that great coteries of woman-workers for justice and righ teousness in our land, including Susan B. A nthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone Blackwell ... and their compeers, Armenia S. White has at last joined her associates on the “other shore”; but, let us fondly hope and believe, her influence for every good cause which she espoused, for every noble work in which she here engaged, will be felt through the years to come, until success is attained and victory results.”

Victory would come three years later, in part thanks to President Woodrow Wilson, who threw his support behind the 19th amendment after watching how women had performed during WWI. “President Wilson could no longer say women weren’t competent,” Tentarelli says. “The country had been relying on them for four years.”

On June 4, 1919, Congress at last voted to approve the 19th amendment, 72 years after the Seneca Falls meeting and 42 years after it was first introduced in Congress. The Exeter News-Letter reported, according to a Seacoast Online story: “Congress heaved a mighty sigh of relief the day the suffrage amendment was wiped off the slate. Even the men who most bitterly opposed it were glad to be rid of the constant heckling of the militant women, who are now jubilant.”

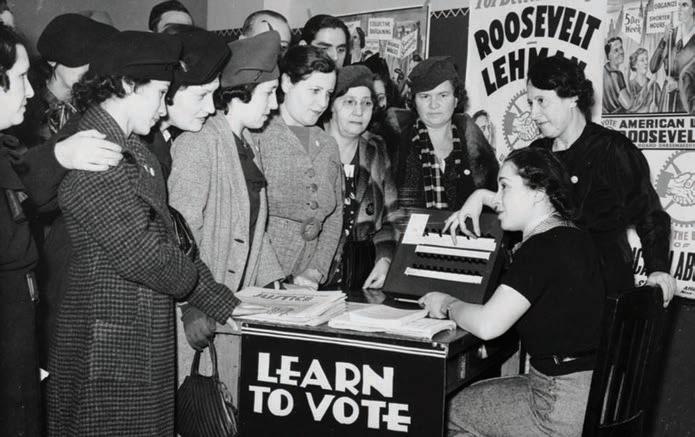

Still, before the amendment became law, 36 states had to ratify it. New Hamp shire was one of the first, voting to ratify o n September 10, 1919. As the ratification process continued, the New Hampshire Woman’s Suffrage Association, t he organization that Armenia White and her husband had founded so long before, changed its name to the League of Women Voters, as would suffrage organi zations in the rest of the country. Betting t hat ratification was certain, the League began an educational process to get women ready to vote.

As women’s right to vote neared ratification, educational programs were set up.

The last state needed to complete ratification, Tennessee, voted in favor of the amendment in August, 100 years ago this month. In November, eight million women voted in the election. In New Hampshire, two women — Jessie Doe and Dr. Mary Farnum — were elected to the Legislature. It was the start of the remarkable story of the powerful role New Hampshire women have played in the civic life of the state.