5 minute read

A Look Back

ALUMNI LETTERS TO DUNCAN CAMPBELL LYLE PROVIDE INSIGHT TO REALITIES OF WAR

BY CHRIS RAGEN

The history of McDonogh is filled with countless individuals who have contributed to the School’s unique and storied legacy. Duncan Campbell Lyle, who served the School faithfully for 46 years as a faculty member and the second Headmaster from 1889 until 1893, is one of those people. During his tenure, Lyle took a particular interest in the futures and successes of the young men who passed through McDonogh, and as such, he created individual scrapbooks about them filled with academic information, club memberships, and clippings from The Week. After their graduation, Lyle corresponded with many alumni and added their correspondence to their scrapbooks. Those who served in World War I often sent letters from the frontlines detailing the struggles of war, life in the trenches, and the comaraderie of the McDonogh alumni who were serving. Following are a few brief stories preserved by Lyle and available in the McDonogh School Archives.

To learn more about the McDonogh alumni who served in World War I and to see the Lyle Scrapbooks, contact Director of Archives & Special Collections Christine Ameduri at cameduri@mcdonogh.org or 443-544-7045.

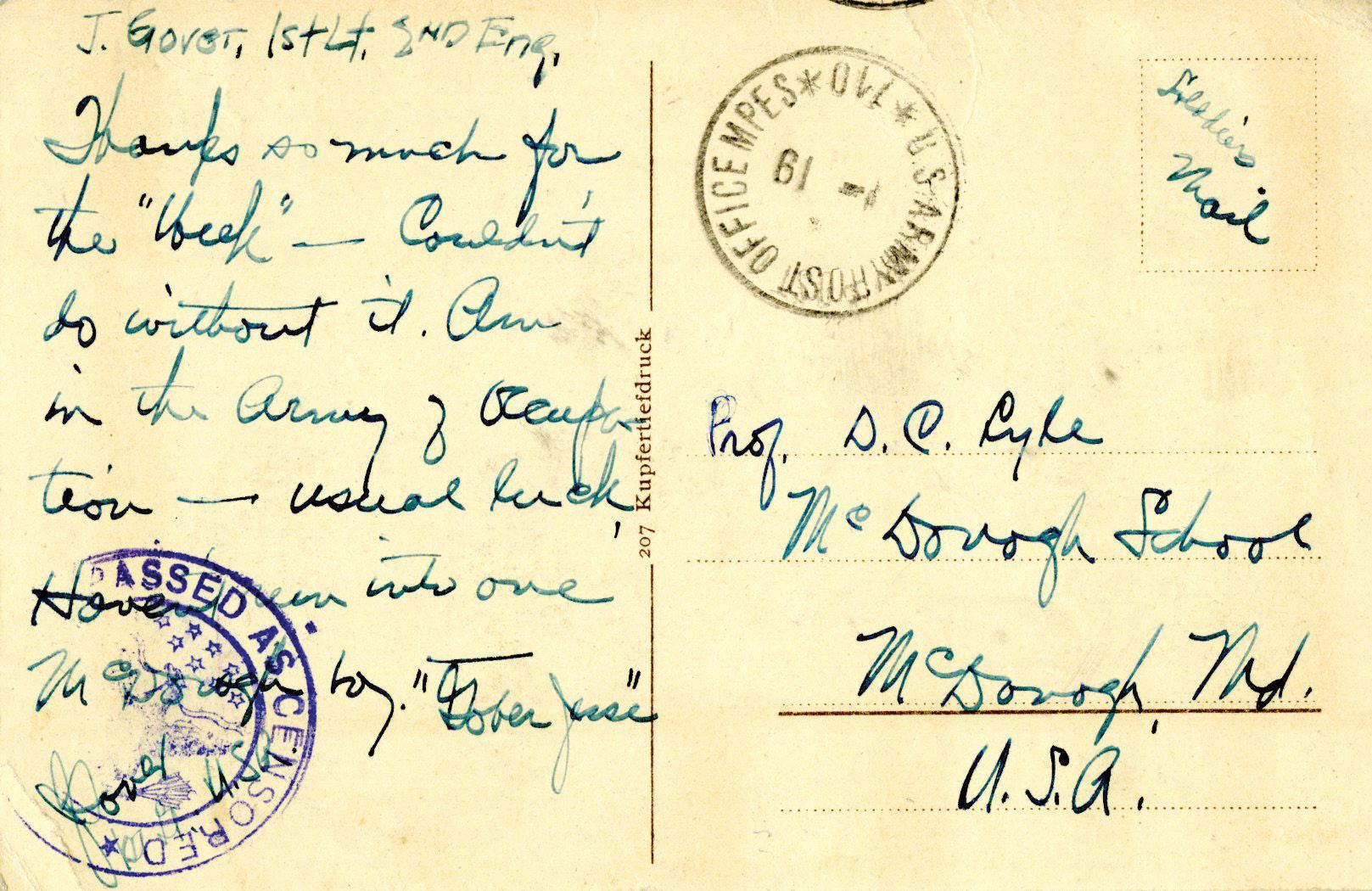

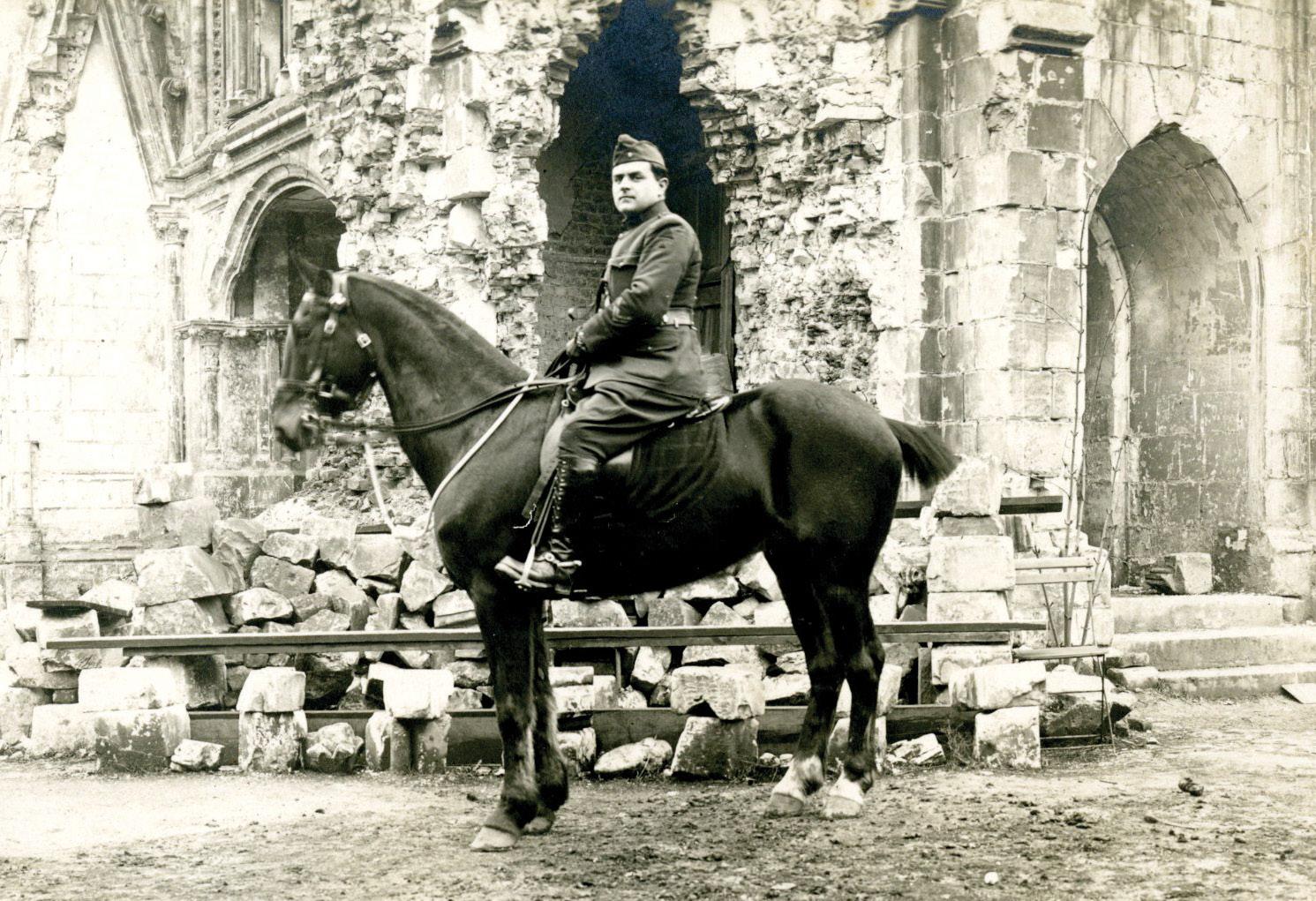

JESSE GOVER CLASS OF 1901

First Lieutenant Jesse Gover served in the United States Army, 2nd Engineers Company F and saw significant action on the Western Front. He wrote home often, offering very frank descriptions of the reality of war. In June 1918, Gover marched his men toward the frontline in France. When they came under intense artillery fire near an abandoned village, he and his men sought cover in the cellars of nearby houses. There he met a United States Marine Corps officer who had also found shelter for his men in the village. In a letter to Lyle, Gover described the encounter and the reality of attrition warfare writing, “I spent the afternoon smoking cigarettes with a Marine officer and making bets on which would be the next house to go. They would knock one down about every ten minutes, after which you would see the first-aid men at work with their stretchers.”

Gover survived the war and later re-enlisted in the Army to continue his service in World War II.

JOHN V. CLIFT CLASS OF 1908

Captain John W. V. Clift served in the Medical Officers Corps and was attached to the British 285th Brigade Royal Field Artillery. His letters to Lyle detailed his living arrangements at the front, the horror of war, life in the trenches and the constantly shifting lines, and many personal anecdotes. In February 1918, he described, “I can’t stand upright in my pillbox, but slide out into my medical hut around the corner to shave and wash in the morning. Practically all out of doors, but I rather enjoy it.”

In spite of his seemingly carefree attitude, Clift admitted that the reality of war was not far away. In December 1918 he shared the story of a dramatic dog fight in which four Allied pilots engaged a lone German plane, causing it to burst into flames and plummet to Earth. After recovering the body of the German pilot, Clift reflected on the nature of aerial combat writing, “…it is easy to understand the short life of the flyers. We see many air fights, but seldom so dire a fall.”

Despite some close calls, including a German advance pushing his field hospital out of that sector, Clift survived the war. When he returned home, he entered into private practice.

PHILIP MCINTYRE CLASS OF 1904

First Lieutenant Philip McIntyre, who served in the United States Army, 115th Infantry Company F, cared deeply for his men and was very protective of the McDonogh boys under his command. One of those was Corporal Harry C. Slater, Class of 1912, who died in France in April of 1919. McIntyre was assigned to carry out the funeral detail, and upon arrival at the hospital, discovered Slater’s body had been mishandled by authorities.

In a letter to Lyle, McIntyre wrote, “When I arrived at Bourbon with the funeral escort, etc I insisted on seeing the body and made the hospital authorities open the box which was already nailed up.” After discovering that Corporal Slater had been wrapped only in a sheet without his uniform or medals, McIntyre demanded that hospital staff provide the proper rites for a military burial. He was subsequently threatened with a court-martial by the ranking officer at the hospital. Despite these threats, McIntyre persisted and secured a full uniform and a proper military burial for Corporal Slater.

McIntyre confessed to Lyle that he could not have lived with himself if he had failed to provide for a fellow soldier saying, “Lord, I never would have been able to write his mother or look anyone else in the face if I had let him be buried the way they presented him to me.”

McIntyre was never disciplined for his insubordination and returned home after the American occupation of the Rhineland in 1923.