4 minute read

The birth of the scam letter

And why we still haven’t learnt our lesson after 125 years

Craig Winter

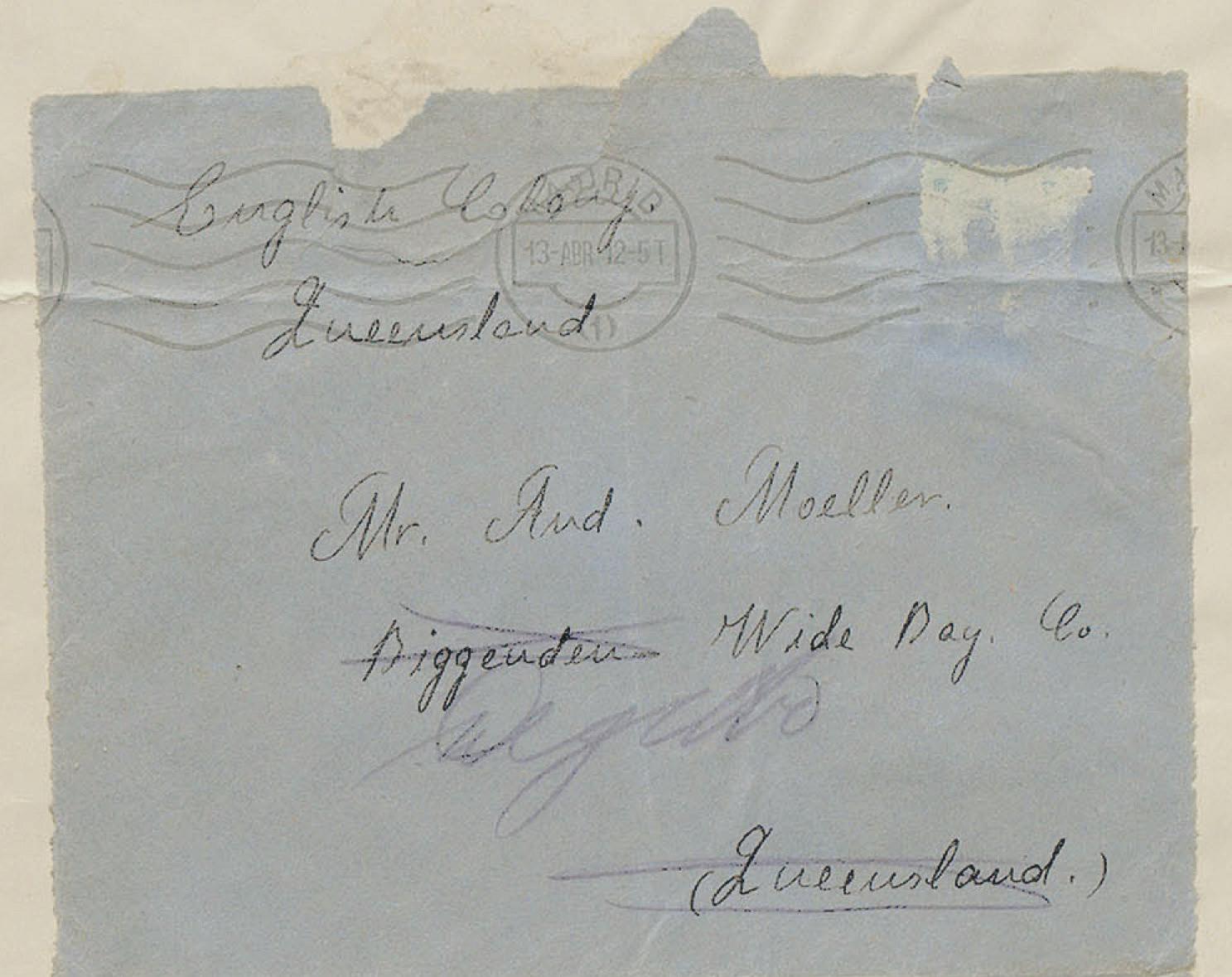

IN 1898, households and businesses across Queensland started receiving strange, handwritten letters from a ‘prisoner’ in Spain.

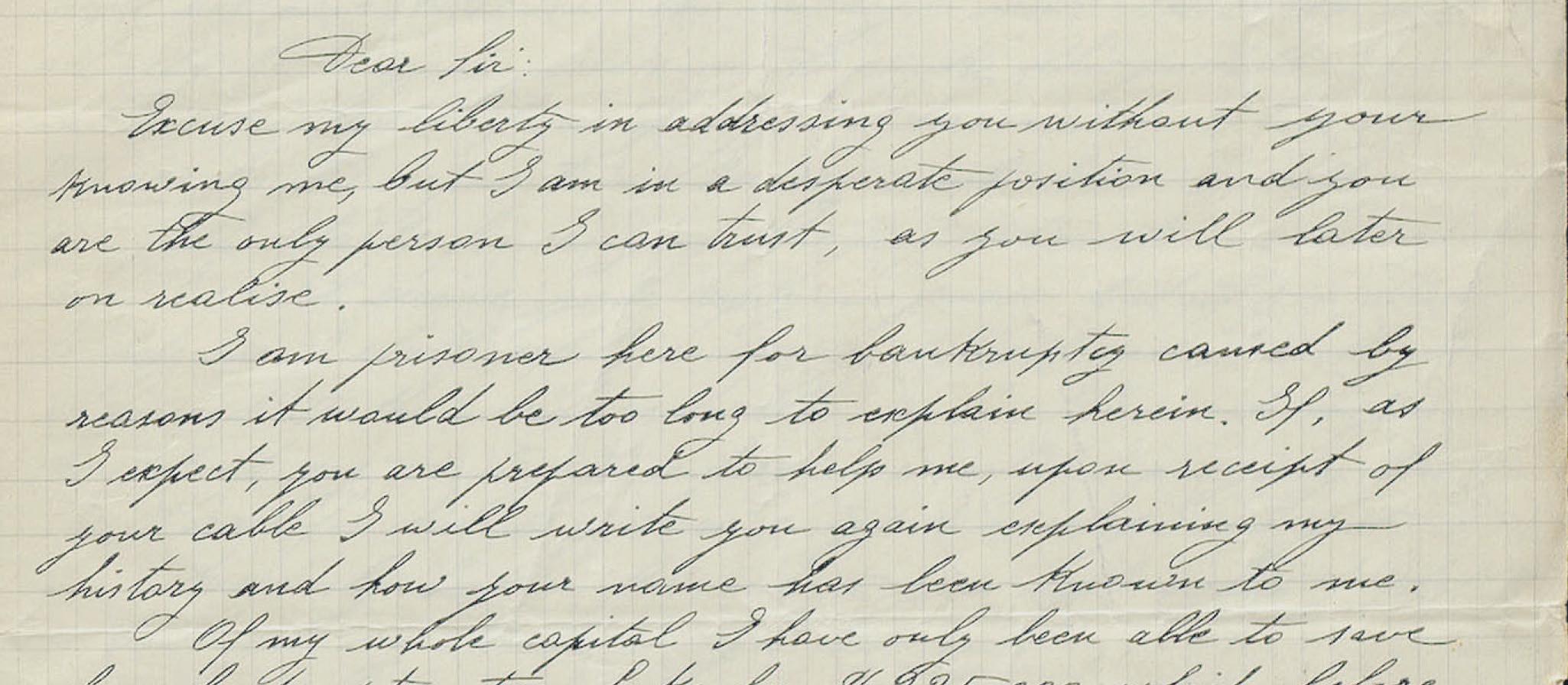

“Excuse my liberty in addressing you without your knowing me, but I am in a desperate position and you are the only person I can trust, as you will later realise.”

Sound familiar?

The carefully scripted letters went on to explain the writer’s predicament.

He was apparently falsely imprisoned and was trying to help his lonely and beautiful daughter who was subsequently unable to fend for herself on the ‘outside’.

With the recipients help, he claimed he could access vast amounts of money, but only after they paid for his court costs and a fine.

The scam letter is nothing new, and in fact todays scam emails continue to use the same story.

Records in the Queensland State Archives reveal these letters had been sent to addresses between Brisbane and Longreach in the hope of snagging elicit donations from as early as 1898.

They continued well into the 1930s, where police reports of the day show they had been referred to

Scotland Yard and other international jurisdictions in the hope of stopping the perpetrators.

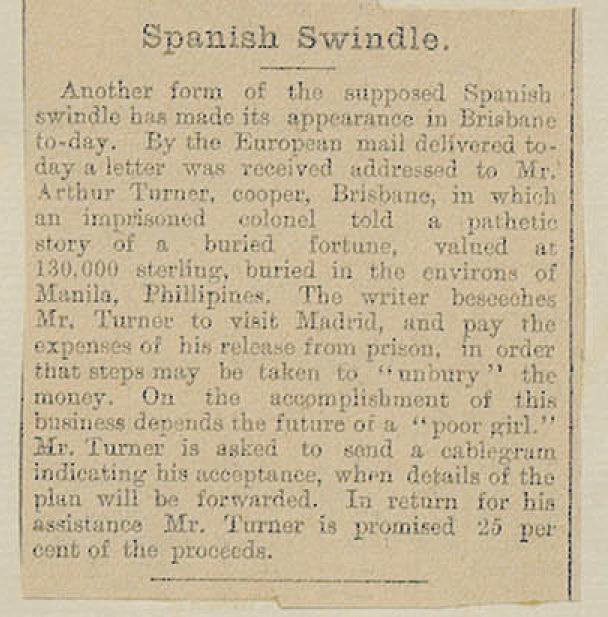

These letters became known as the Spanish Swindle.

Police ascertained that they were mostly written by Englishmen and posted from Spain.

Todays equivalent predominantly appear to come from Africa, thus the tag ‘Nigerian Prince’ scam.

Why do these scams still work, even though we have over 100 years of experience with them?

Social psychologists say that they are the ‘perfect storm’ of temptation.

“These scams play on people’s greed and ego.” says Dr Frank McAndrew.

“Many times, the scam is set up in a way where victims are promised that they’ll make a huge financial profit without much effort.”

“In most successful scams, the fraudsters also prey on your desire to be a hero.”

“People think ‘What if it’s true’ but of course it never is.” he said.

Data from the 2021 Targeting Scams report revealed that Australians lost more than $2 billion to scammers that year.

Total losses more than doubled on the previous year’s total loss of $851 million, and recent reports say that over $3 billion was lost in 2022.

Back in 1898, people were parting with sums of up to ₤300 - the equivalent of around $40,000 these daysa huge amount of money.

The similarities are all there. Not much has changed.

The psychology of these scams is the same as a hundred years ago, so don’t feel bad if you’ve been conned.

Despite all the publicity, warnings and proof that these contacts are fake, people are still falling for them.

“We all like to think we can have a windfall, easy money, but the truth is, if it’s too good to be true...it absolutely is”

Let’s all start learning from the lessons of a century ago.

If you’ve sent money or shared your banking details with a scammer, contact your financial institution immediately. They may be able to stop a transaction, or close your account if the scammer has your account details. Your credit card provider may be able to perform a ‘charge back’ (reverse the transaction) if your credit card was billed fraudulently.

If you suspect you are a victim of identity theft, it is important that you act quickly to reduce your risk of financial loss or other damages.

You can contact IDCARE - a free government-funded service which will work with you to develop a specific response plan to your situation and support you through the process. Visit the IDCARE website or call 1800 595 160 or apply for a Commonwealth Victims’ Certificate - a certificate helps support your claim that you’ve been the victim of identity crime, and can be used to help re-establish your credentials with government or financial institutions. Visit Victims of Commonwealth identity crime at www.homeaffairs.gov.au