9 minute read

Lookout Point Sonny Longtine

The Marquette County Courthouse, built in 1904 with Marquette sandstone, is an iconic Romanesque Revival building that in 1958 was site of the filming of the blockbuster movie, “Anatomy of a Murder” that starred Jimmy Stewart, Lee Remick, George C. Scott and Ben Gazzara.

SOLID HISTORY

Advertisement

U.P. communities rebuilt using sandstone after devastating fires

Story and photos by Sonny Longtine

Fire! In the later years of the 19th century, no other word could instill more fear into the hearts of residents by the shores of the world’s largest fresh-water lake in the cities of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Devastating fires had razed entire business districts in Marquette in 1868, Hancock in 1869, and Red Jacket (Calumet) in 1870. The fire in Marquette alone destroyed more than 100 buildings. The small Upper Peninsula towns were devastated by the fires.

It became imperative that wood structures be replaced with either brick or stone—anything not so easily combustible—and sandstone became that replacement. Lake Superior sandstone was highly prized for its beauty and toughness; it was well suited to rebuilding Upper Peninsula towns. The great fires also led many towns to adopt fire codes and to acquire adequate firefighting equipment.

Lake Superior sandstone was quarried in three primary locations: Marquette and Jacobsville in the Upper Peninsula and Bayfield, Wis. Although there were more than 70 sites in the Lake Superior region that quarried sandstone, most did not compare with the volume produced by these three.

The sandstone quarried in Marquette was called brownstone because of its brown-purple hue, while the sandstone quarried in Jacobsville was called redstone, again because of its coloration. Bayfield primarily produced redstone, although colors ranged from pink to light brown.

Marquette sandstone was extracted from a quarry close to Lake Superior in South Marquette, while the Copper Country sandstone was quarried at Jacobsville, a small location in the southeast corner of the Keweenaw Peninsula and near the Portage Canal. The highly sought sandstone was shipped to the Midwest cities of Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Chicago, and Detroit, and to other points south. Chicago’s Tribune Building, the Germania Bank in St. Paul, and the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York, all prestigious and well-known buildings, are among hundreds of structures that were built with Lake Superior sandstone. Its quality and durability was nationally recognized. The burly stone was not only aesthetically pleasing but also fire resistant. Sandstone can endure temperatures up to 800 degrees before it will crack or crumble. Granite and limestone cannot endure exceedingly high temperatures as sandstone can. In the Upper Peninsula where 80 degrees is considered a heat wave, but where fires had ravaged towns, there was little hesitation in using the sandstone.

Sandstone can not only withstand extreme temperature changes, but is able to retain solar heat in the winter. Not only was sandstone easily obtainable but there was a ready workforce in the Upper Peninsula to process it. It was ordained for greatness as it became the material used in many of the peninsula’s finest courthouses, commercial buildings, and homes.

The demand for sturdy and sizable buildings was also driven by the prosperity created by burgeoning iron ore and copper mining in the peninsula in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Money was now available for

imposing buildings, and community movers and shakers wanted buildings that would make a statement about the excellence of their town. The hard-wearing Upper Peninsula sandstone was utilized in Richardson Romanesque, Italianate, and Gothic architectures.

Numerous historic sandstone structures across the peninsula have been torn down in the last five decades; fortunately, however, many still remain. From 1880 to 1910, sandstone was a central building material in Upper Michigan. Sandstone was quarried in several different ways: dimension stone, ton stone, or rubble stone. The most costly and the one that many builders preferred was dimension stone. This stone was removed from a quarry in blocks that measured eight feet by four feet by two feet. Contractors then cut the stone to the shape and size that was required for a specific building. Rubble stone was the by-product of dimension stone and was used for cribs, breakwaters, and building foundations. It was the cheapest sandstone and the least desirable, although it often served well on given projects.

When not used for these projects it was often discarded. Quarrying stone by the ton was another method. It was shipped to builders in large uncut chunks and sold by weight. In 1873, the Erickson Manufacturing Company in Marquette installed rock saws that could cut the stone into different sizes and shapes. Previously all sandstone was shipped in the rough; now it could be cut into square and rectangular blocks. Windowsills were one of the most common cut blocks.

Sandstone hardens after being removed from the quarry. Once the stone is exposed to air, the water in the sandstone is drawn to the surface and the mineral residue (a clay-like substance) in the water is deposited on the stone’s surface. During the drying cycle, the residue serves as a bonding and hardening agent, making the stone extremely durable. In testimony to its durability, there are many sandstone structures still in use in the Upper Peninsula more than 100 years old.

A reporter for the Marquette Mining Journal in 1871 extolled the virtues of Marquette sandstone. Proudly he said, “The stone of Marquette… remains intact in places amid the hottest heat…” Marquette sandstone has a purplish brown color that many consider aesthetically superior. It also appears as though drops of rain are embedded in its surface.

Prices for sandstone were a bargain when compared to today’s building materials. Marquette sandstone sold for $1.30 a cubic yard, while Jacobsville sold for $1.20 a cubic yard.

Although most sandstone in the U.P. was quarried in Marquette and Jacobsville, there were more than 15 companies that extracted the stone in Marquette County. The Marquette Brownstone Company became the primary producer in the county. Today, the former quarry site in South Marquette has a condominium development that surrounds the now water-filled quarry pit. Much to the delight of the condominium owners, it serves as a private swimming pool.

Sandstone fell out of favor after the first decade of the twentieth century and was replaced with the preferred lighter-colored granite and Bedford limestone. In 1904, Peter White Public Library in Marquette became one of the early buildings in Marquette to adopt the up-and-coming limestone (1904).

Other contributing factors to the demise of sandstone was the depression of l893 and the increased use of artificial stone that was cheaper and more accessible.

The Columbia Exposition in

St Paul’s Episcopal Church on E. Ridge Street in Marquette, designed by local architect C.F. Struck, was built in 1875. The Romanesque Revival edifice was constructed with native sandstone and has an impervious slate roof.

The Phelps Richardsonian Romanesques Revival house on E. Ridge Street was built in 1892. The sandstone dwelling was a wedding gift from William Fitch to his Daughter Mary who married Peter White Phelps.

Chicago in 1900 was another force that initiated sandstone’s demise. The Exposition was called the “Great White Way,” and its use of the light-colored granite and limestone ushered in the new material of choice, and sent the colorful sandstone into near oblivion. Along with the rise of Philadelphia hard-pressed brick as another good building choice, sandstone continued its downward spiral.

When a sandstone building caught fire, most often the interior was gutted and the sandstone carcass remained. These buildings could be rebuilt when the existing sandstone walls were intact; St. Peter Cathedral in Marquette is a good example. When the cathedral was gutted by fire in 1935, the sandstone walls weathered the fire and an even grander cathedral was built. The fire originated in the basement when a coal bin spontaneously combusted.

Other sandstone buildings in Marquette were torn down to make parking lots. The Marquette Beauty Academy and the Nester School, both on Bluff Street in Marquette are sites where blacktop replaced historic structures.

The most egregious tear-down, however, was when Northern Michigan University (NMU), ripped out three historic sandstone buildings that were built at the beginning of the 20th century. Kaye Hall, Peter White Hall, and Longyear Hall were unceremoniously demolished when university officials decided they needed a larger and more modern administrative building. In 1975, concerned local citizens banded together in an attempt to save Kaye Hall, the parapeted central building with a marble staircase in a threestory atrium.

Their effort failed.

In place of the historic buildings, a six-story, box behemoth was erected. Universities like Notre Dame and Michigan State University went to great lengths to preserve their historic buildings. The only NMU buildings left after the demolition were those built after 1950. A visitor to the campus would not have any idea that the university’s inception was 1899.

With no one quarrying sandstone for decades in the Lake Superior region, the supply for restoration projects is limited, and stone masons who work with sandstone are few and far between.

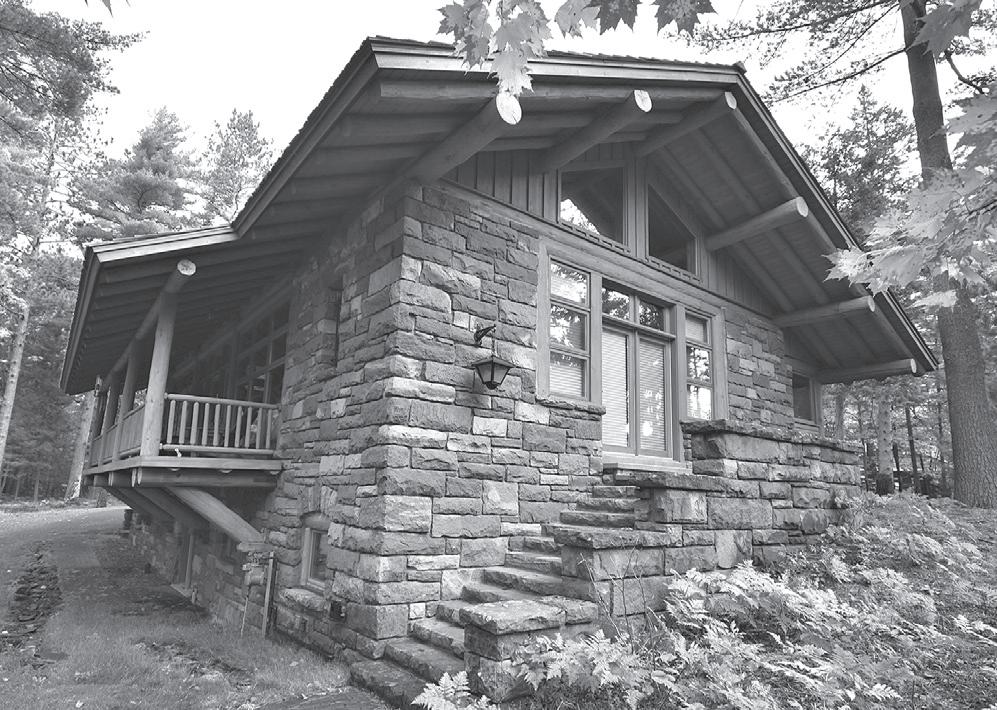

Dave Holsworth, a 54-year-old, skilled stone mason from Republic, Michigan, is one of the few left who still works with sandstone. His most recent sandstone renovation project was at the home of Marquette entrepreneur John Jilbert, who owns a classy log and sandstone house on the city’s outskirts.

Holsworth built a massive sandstone fireplace for the Jilbert house. “I like working with sandstone,” Holsworth said. “It’s lightweight and sets up quickly, just what you want. A hard stone like granite is more difficult to work with.

In addition to building the fireplace, Holsworth repaired or replaced sandstone that was used throughout the house. Holsworth commented, “Sandstone is one of the better stones to work with, it’s a soft stone, easy to chisel; it carves easily.”

Holsworth also repointed (placing wet mortar into joints in repairing old masonry) the Jilbert sandstone dairy building located in Marquette. “Keeping sandstone moist when you’re repointing is a must,” said Holsworth, “otherwise it dries out too quickly and crumbles.”

Holsworth pointed out, “It’s really hard to find sandstone anymore. I was lucky in the Jilbert project that there was a huge pile of sandstone at the house site that was left over from a 1930s county park project.” Many of the pieces Holsworth used were large and needing trimming. He said, “I had to use a masonry saw to cut them down before I could chisel them to fit.” Jilbert was fortunate to find Holsworth to complete the masonry work on his rustic but elegant home.

Astonishingly, the Upper Peninsula radically benefited from the 1860s fires that destroyed major portions of several U.P. cities. These fires led to a sandstone building boom that resulted in long-lasting, functional structures that are still in use today. They enhance the U.P. with a stylish elegance that “yoopers” can unabashedly embrace.

Stone mason Dave Holsworth of Republic is one of a few area masons who work with sandstone. He crafted a large fireplace out of sandstone at the John Jilbert residence near Marquette recently.

About the author: Sonny Longtine is a Marquette resident who has published eight books on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. For more than three decades he taught American history and government in Michigan schools.

MM