16 minute read

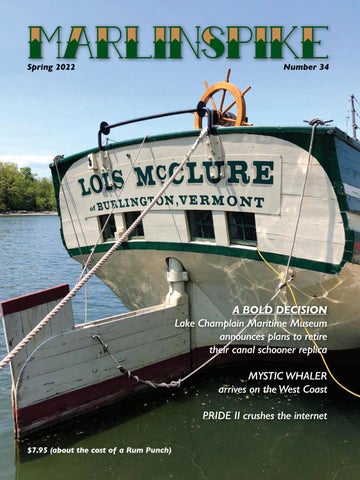

A Bold Decision

The Lake Champlain Maritime Museum announces they will allow their replica canal schooner, the LOIS MCCLURE, to die with dignity after her 20th season in 2023

In March, the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum announced that it would “retire” its replica canal schooner Lois McClure in 2023.

Advertisement

The McClure was launched in 2004 with the goal of understanding the canal schooners, how they were built and operated, and the impact of the canal system. Over the ensuing two decades, the Lois McClure proved to be an effective teaching tool, touring Lake Champlain and the connecting waterways and bringing this history to local communities.

But the replica now requires “increasingly extensive repairs that push beyond the goals of this replica project. With that in mind, the Board of Directors voted unanimously to retire the replica… and conclude the replica project.”

After October 2023, the Lois McClure will be disassembled. Parts of the boat will anchor a new exhibit at the Museum, opening in 2024.

The Museum has invited the public to share memories, stories, and photos to become a part of the Archiving Project. The Museum will also be conducting oral history interviews with members of the replica building project, volunteers, and staff.

Marlinspike spoke with Susan Evans McClure (no relation) the Museum’s Executive Director, shortly after the announcement.

Marlinspike: Susan, I’m sure you expect us to be foaming at the mouth about this decision. But I believe this is an important issue for our industry to address.

Our boats don’t “retire”. They get sold, they get repossessed, they get abandoned, they get broken up, they sink at their docks — generally, it doesn’t end well. Retirement sounds like a civilized outcome, compared to some of those options. We do a terrible job in this industry of moving on from vessels.

Susan McClure: We’ve actually been working on this for two years, just to tell the public about it now. But when we first started thinking about it, two years ago, I started reaching out to other organizations with replicas, because I believe we should all be learning together, and I thought, man, maybe we don’t know how to do this, but somebody else must have figured this out! I talked to so many smart, committed, amazing, talented people who care about the public and care about their boats — and no one had a perfect way of doing this.

MS: Tell us what got you started down this path. You said “two years ago” and of course that sets off the COVID bell in my head.

SM: Actually, I would say this is probably the only thing that we’ve done in the past few years that was not impacted by COVID.

Of course, we were impacted — but the decision was not. We’ve been thinking about this for several years. I’ve been at the museum for about three years and it was really two years ago, just pre-pandemic, when we started thinking, what is the long-term plan for this boat? And reflecting on what is most important about this project to the Museum and to our public. We talked a lot internally, with our volunteers and supporters and crew members.

I wasn’t involved in the build, but I lived in Burlington the summer the Lois was being built — it was my first summer in Burlington. I would go down to the waterfront and see them building this amazing boat. And when I came back to Burlington the next summer, I said, “Okay, what boat are they building this year?” I thought that’s just what they did in Burlington, every year. But it’s not — it was a once-in-a generation thing.

So we’ve been looking at the long-term plan for a while, thinking about the maintenance of the boat, and where the boat has traveled and what the boat has accomplished. The boat had over 300,000 visitors in the past 20 years! But at the same time, the average lifespan of a 19th century canal boat was 15 years. And we were already past that.

Of course, we were not moving tons of logs and freight and iron on the boat every year, like the boat would’ve been doing in the 19th century, but we still had traveled consistently and put a lot of miles on the boat.

You could also say we were having a historically accurate problem. These canal boats never wintered on Lake Champlain because the Lake is so rough in the winter. They would take them to New York, to the Hudson River, into the canals. And they would raft up a bunch of these canal boats together and the families who lived on them would send their kids to school together, they’d live this communal lifestyle in the winter months. And the boats would actually freeze into those harbors.

But we had been keeping it on Lake Champlain. About three years ago, we did have to move the location of our winter storage, and it got us to thinking about the lifespan of the boat.

In 2019, we hauled the boat out of the water and did work below the waterline with these really amazing shipwrights. And one of them pulled me aside and he said — and again, this is my first position as director of a maritime museum. He pulled me aside and he said, “Look, I work on these boats everywhere on the East Coast, and no one has a plan for this.”

He said — and this really stuck with me — “What I have seen at other locations is that no one wants to make a plan and no one wants to talk about it.”

So people just let these boats, these amazing boats with amazing stories, they just kind of let them fall apart. And it’s really sad. Nobody wants to see that. So his plea was: please make a plan that honors this boat and what it’s accomplished.

MS: If he was looking at the boat and thinking about the end of her lifespan, then I take it she wasn’t structurally in terrific condition.

SM: I mean, the USS Constitution exists, right? You can keep a wooden boat around forever. You just have to rebuild it constantly.

MS: Sure, if you’re the United States Navy and you have that kind of budget.

SM: Exactly. And that was kind of what he was getting at. He said, “You could do it…”

MS: You could do it. But you were looking at a major structural rebuild.

SM: Yes. And having to plan to do that over and over again, every ten years, and the cost incurred with that. So we took that into account and we said, “Can we make a shorter term plan?” And then we brought in a shipwright last summer to assess the boat, and he did say that it needed some significant, immediate work to stay seaworthy.

And in addition to the regular rebuilding work, these boats are incredibly expensive to maintain. We have full-time staff who work on that. In addition to these major haulouts, they’re rebuilding and fixing as they go. And it’s very expensive every year to just keep the boat in the water.

MS: Our industry always includes a number of boats for which the maintenance is more than the potential for bringing in revenue. Did you have solid numbers on what the schooner cost to maintain, as opposed to what its contribution was to your bottom line?

SM: Yes, we did. I don’t want to make it sound, in this case, like it was completely about money. Because yes, it’s a very expensive endeavor, but lots of amazing things in this world are expensive, and that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do them. Partially it’s expensive, and partially the audience for funding projects like this is very different than it was 20 years ago.

There are a lot of boats that were built 20 years ago, because it was kind of the thing to do. It was what maritime museums were doing, building these big replica boats. And they’re amazing. Nowadays, not as many places are doing it anymore. There are a few of course, but the ways that those projects got funded has changed dramatically over the past 20 years.

At the same time, we have been thinking about how we tell this story in a way that gets even more people connected to it. We’re really focused on accessibility in everything we do. Access to the water. How do people get to be on Lake Champlain as private property spreads around the lakefront and it’s harder for regular people to get to the water?

We try to get people access to the lake, but also access to our facilities for people with disabilities. Replica boats are inherently not accessible. Everybody does their best, and it’s not for lack of trying. But one of the things we were excited about was the opportunity to rethink the experience of a replica boat through a universal design and accessibility lens.

So our plan is to run the next two years with the boat on the water, back in our museum. We won’t be traveling, but it’ll be on the water. And I don’t want to make it sound unsafe, it’s perfectly sound and totally safe. But after that, the plan is to develop a new exhibit, that is fully accessible, about canal boats. Nothing will ever be the same as standing on the deck of that boat and feeling the wind from the lake. That’s the real thing, you can’t change that. But we are hoping to recreate some of those feelings in a way that is accessible to everyone.

MS: You make a distinction between restoring original vessels — in this country we have USS Constitution, Charles Morgan, Elissa, and any number of original fishing schooners, pilot boats, and yachts — and restoring replica vessels, like the Lois McClure. That line got blurred in the last couple years, when Plimoth Patuxet came out and said that their Mayflower replica, built in the 1950s, is herself a historic vessel and worthy of recognition as a historic landmark. And they spent many millions of dollars rebuilding her.

Did the status of the McClure as a replica vessel carry a lot of weight in your debate over what to do with her?

SM: Absolutely! If this boat were an original 1862 canal schooner, we would not be talking about it this way.

Replicas are teaching tools, tools to use to meet your mission. That was the intent twenty years ago, going into this project. The thing that led us to developing the archiving project that we announced this week, was to attempt to capture what has grown up around the boat during those twenty years.

The boat is a replica, but the thing that happened when we built this replica — bringing a community together, connecting with real people — that’s a real thing. That’s something we want to quantify and qualify.

One of my early phone calls was with some longtime partners in this project with us, the New York State Canal Corporation. One of their staff told me a lot of these cities on the Erie Canal grew up with their backs to the water. When the Lois McClure visited port cities along the canal, that was one of the first times that something had happened to draw people to the waterfront of these canal communities.

She said, “The experience of the Lois visiting actually changed the way these towns saw themselves in relation to the water.

“It would start with the Lois visiting. And then next summer, a group of people would say, ‘Maybe we should have a festival on the water.’ And then the next summer, someone would say, ‘Remember last year we got all those people together on the water? We should do that again.’

And then the next summer, they were like, “We should build a bike path on the water, this is great way to connect with it.” And then the next summer, there’d be a restaurant that popped up, right on the canal.

It is bigger than just building a boat. That’s something we want to make sure we’re capturing and documenting, taking the time over the next two years to document that. I think will be a helpful project both for us, but also just to kind of write down how awesome it was.

MS: Did you encounter a lot of resistance to the idea of retiring the vessel?

SM: No. But I don’t want to make it seem like it was an easy decision at all. For many of our staff, including me, there is a sense of loss, and it’s sad and it’s hard. It has been a process with many of our staff to get there, and not every single person thinks it’s the best idea in the world. But the vast majority of people on our staff — actually, now I would say all the people on our staff — are fully on board with the plan.

And honestly the plan came from them. It wasn’t that our board came in and said, “Hey, we should do this.” It wasn’t that I came in and said, “Hey, this is what we’re going to do.” It was through talking with our staff and coming together to make a plan that we brought it to the board said, “Hey, this is the recommendation from the staff, based on the research we’ve been doing, what we’ve been experiencing. Here’s what we think we should do next.”

And our board saying, “Yeah, we think that’s a great idea. We’re listening to what you’re doing.”

MS: Now, do you face a rebranding issue? For a lot of us, our boat is the most visible and recognizable symbol of our organization. Maybe it has stopped pulling its weight — maybe it’s dragging us down — but it’s been featured on our signage and our mailings and our website for decades! And now we have to distance ourselves from it. Is that a rebranding challenge for the Museum?

SM: Our plan is still to have an exhibit and have the story of canal boats as a centerpiece of our museum. So that won’t change. I think for us, because the boat was a touring project and it was often away… it was kind of the flagship for the museum.

In our region, we’re still connected to a lot of people through the other programming that we do. We have an archeology team and we do exhibits and we have a boatbuilding program and we’re in every school. So it is key to our museum, but it’s one of many, many, things that we do. And we’re not going to stop talking about canal boats because the schooner is off the water.

MS: Getting back to your discussion with that boatbuilder. Why don’t we talk about these things? Why is it so difficult for organizations to plan for the eventual obsolescence of their vessels?

SM: Not to get too large-minded here, but it’s our society’s inability to talk about death and change. Boats are objects, but both have a spirit about them and they feel alive and they all have a personality and an identity. And it’s hard.

We humans personify maritime vessels; we always have, right? You look at European churches, in Portugal, in the 15th century, they had ship models in the churches because it was important to have the boats that were part of their life be living things.

In some ways, it’s no different from the fact that it’s very hard for my mom to talk about the inevitability of when she won’t be able to drive anymore and will have to go to a retirement home. She won’t talk about that either.

MS: None of us want to end up in the shallow end of the harbor with mud in our bilges and our paint peeling off and our masts broken off at the deck.

But if you don’t talk about these things, or plan for these things, the outcomes are not going to be pretty.

SM: Exactly. And that is what we wanted to avoid. I think we are doing something different, in that most organizations wait until they know exactly what’s going to happen before they tell the public. One of the cornerstones of this project is that it has always been a public project. It was built in front of the public in a major city. It was built by volunteers. It’s public. The public is at the heart of this project.

So we want to say to the public, “Help us get through the next two years.” What are the events that you need to say farewell to this boat? What are the stories about it that stick with you, that you want us to keep telling? What are the new ways you think we should be interpreting it?

We don’t have an exact plan and graphics. I don’t have a schematic of the new exhibit that I can trot out and say, “This is going to be amazing. This is what we’re going to do.” Because we want to be creating that with the public, the way we always have for this project.

That is, I acknowledge, a different approach than most organizations go for. But it’s how we operate. And it felt like the right thing to do.

MS: If this goes well, I think you will open people’s eyes to another path that can be taken. Not every boat can or should live forever.

It’s very difficult when you’re in charge, and your crew, your staff, your volunteers are all attached to this vessel and they’re looking to you to somehow make it work. But instead you stand up in front of them and say, “It’s not going to work.” It takes guts.

SM: Thank you. I hope we will find a way that people can think about it and learn from us, right? Everyone makes mistakes as they’re learning new things. I’m sure there will be missteps that we make in the next two years, but hopefully we’ll get a lot of things right too.

And hopefully we can be a place that people can learn from because they know we’re not alone in making these plans. Every decision we’re making is with the best interest of the boat at the center.

For more on the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum and their many programs, visit LCMM.org.