19 minute read

My Personal Khrushchevka

from Power, Architecture and Ordinary Citizens: A Study of Nikita Khrushchev’s Mass Housing Campaign

by marialisnic

Khrushchev’s Housing Reality

Thirty-two years ago, the Republic of Moldova: the country where I was born and lived most of my life, had been known as Moldavian Socialist Soviet Republic, or simply MSSR. This country disappeared in 1991 with the dissolution of the USSR and the collapse of socialism, just ten years before I was born. I have not lived a day in Moldavian Socialist Soviet Republic; however, the ghosts of the past keep percolating into my life, as the “new” urban reality constructed across all Soviet Union republics by Khrushchev’s mass housing campaign is still in place. Buildings did not collapse with the regime which produced them; they continued to stand still while the world around them did a U-turn.

Advertisement

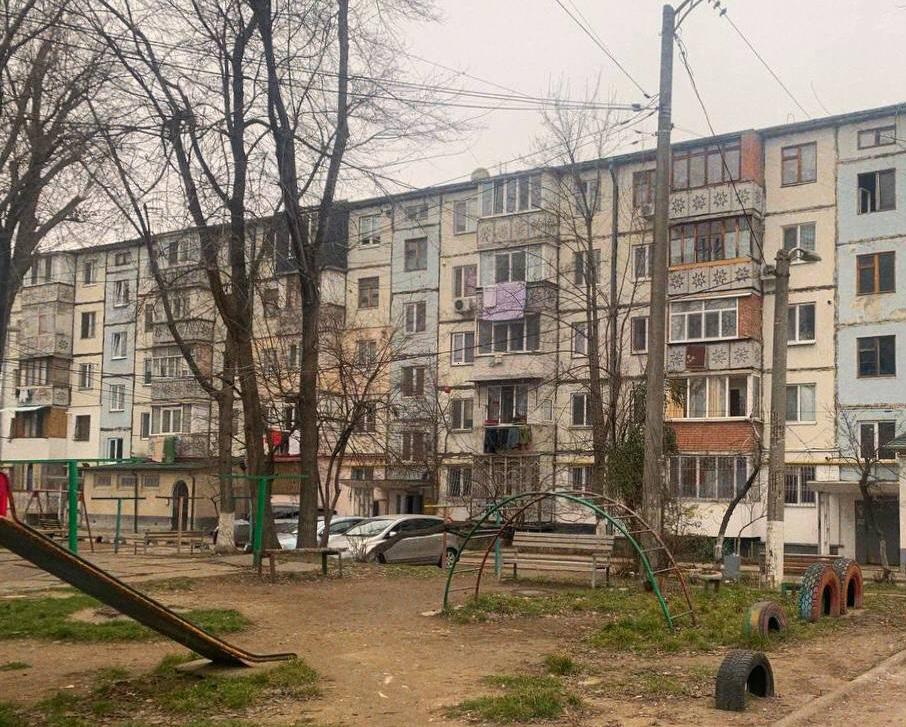

I grew up in an apartment on the fifth floor of a housing block in the Riscanovca district of Chisinau, the capital of the Republic of Moldova. This district began to develop in 1958 when the Soviet State, led by Khrushchev, launched the mass construction campaign there.59 The exact year of my block’s construction is unknown; however, it was built around the beginning of the 1960s. The structure is made of large coquina blocks and presents four section cascade, conditioned by its location on a slope.60 Compared to the nearby rectangular “box” houses built around the same time, this cascade block stood out to me as both intriguing and beautiful. The Soviet uniform cityscape was more than just photographs or book pages for me; it was a reality in which even minor changes in design could delight. Unlike academics, I did not see the uniformity and typical construction as oppressive and psychologically debilitating, at least from the outside, not because of the ideological propaganda or a sense of equality imposed by the Soviet State but because this was the only housing reality I knew.61

59 Galina Makisheva, Riscanovca – raion dlia bednih jiteley [Riscanovca – district for poor citizens]

(2019) <https://bloknot-moldova.ru/news/kogda-to-ryshkanovka-byla-nishchey-okrainoy-stolits-1145982>

[accessed 12 January 2023]

60 Typical mass housing in the Soviet Union was mostly built with concrete pre-fabricated panels, whereas in the MSSR large coquina blocks were used for housing construction alongside, including my own apartment block.

61 Mark B. Smith, p.112; Blair A. Ruble, p.251

My parents bought the three-bedroom apartment in the housing block mentioned above in 2001, before I was born, to accommodate their growing family of four, soon to be five. After a lengthy search, they finally settled on our current apartment, with the location being the deciding factor in their choice. My father always liked to remark how lucky we are to live in such a good residential area which provides all the necessary social, recreational and commercial services within walking distance. During Khrushchev’s mass-housing campaign, it became important not only to build individual housing units but also to create new residential systems known as microdistricts (mikroraion). These districts included functional zoning to separate housing from services and industry, incorporated green areas serving as vital passageways, and provided all social and commercial services. 62

Nevertheless, new residential districts often failed to live up to their ideal design, as in practice, the open spaces between apartments became “empty voids” which lacked the planned recreational facilities. In the worst cases, buildings sprouted in unlit and unpaved areas with hardly any infrastructure, public transportation, or access to social services and stores. 63 This was not the case with the residential area surrounding my apartment building, as it was one of the few to put theory into practice. Two parks are within five minutes of walking distance from my apartment. In close proximity are several kindergartens, schools, and a hospital. These and other amenities were planned and constructed concurrently with the apartment buildings under Khrushchev’s rule. Since there were no private landowners in the Soviet Union, the municipalities and their planning, architectural, and construction agencies were free to let their collective imagination determine the size and shape of major construction projects, including the design of the mikroraioni.64 Such a monopoly in the construction and service provision implied that if the State did not provide all the needed amenities, no one else would. As a result, some microdistricts became “socialist bedroom communities,” while others, including mine, became the realisation of ideal residential area design.65

My parents intended to move into their new apartment after minor renovations. Still, the apartment’s condition thwarted their plans, as the previous owners left everything from furniture to walls in dilapidation. My parents decided that if they could not avoid major construction works, they might as well completely redevelop the typical khrushchevka to their needs and tastes. The redevelopment of Soviet mass housing apartments became an increasing trend among the citizens of post-Soviet states. Khrushchevki unquestionably resolved the housing shortage, and at the time, many of those who received new apartments were ready to close their eyes to design flaws and deficiencies. Many continued to live in State-provided separate apartments after the dissolution of the USSR, but the political and social situation around them changed, as did people’s priorities and desires. Numerous online resources provide information on how to redevelop a khrushchevka, ranging from initial design advice and an overview of planning legislation to examples of the replanned layout and photographs of numerous redeveloped khrushchevki.66 Some design and architecture firms, such as Moscow’s planning and design studio “Colosseum” (“Kolizey”), even specialise in the redevelopment of khrushchevka.67

62 Blair A. Ruble, p.248

63 Steven E. Harris, p.201

64 Blair A. Ruble, p.249

65 Ibid., p.249

66 An example of a web page providing information on how to redesign a khrushchevka: Pereplanirovka khrushchevki: idei dlia vseh tipov kvartir i gotovie plani [Redesign of khrushchevka: ideas for all the types of apartments and complete plans] (2022) <https://www.ivd.ru/stroitelstvo-i-remont/organizaciya-i-podgotovka/pereplanirovka-hrushchevki-91832> [accessed 12 January 2023]

67 Studia proiektirovania i dizaina Kolizey [Planning and design studio "Colosseum"] (2023) <https:// www.spd-kolizey.ru/uslugi/pereplanirovka_kvartir/khrushchevki/> [accessed 12 January 2023]

According to Christine Varga Harris, architectural and urban forms in the Soviet Union concluded and symbolised the regimes that fostered them. She viewed “the simplicity and modernity” of Khruschev’s architecture as a representation of the regime’s “populism and intention to realise the egalitarian ideals of communist ideology”.68 In this context, the tendency to replan and reconfigure the Khrushchevki in the post-Soviet Union States may represent a withdrawal from the individual oppression and dejection imposed by Soviet ideology and the mass housing campaign to revive individuality and the importance of consumer needs consideration in the new capitalist reality following the dissolution of the USSR.

Reimagining Khrushchevka

Although I had always been aware that our apartment was replanned, I must admit that seeing the original plan left me feeling a little taken aback. I could not imagine how we would live in this apartment if the previous layout remained in place. At that moment, I felt extreme gratitude toward my parents for transforming our domestic space, as well as frustration and sadness for those who were pressured to reside in such cramped, inconvenient apartments. One chairman of the residential “assistance commission”, Iakovlev, described Khrushev’s separate apartments as “small dormitories” while expressing his dissatisfaction with the excessive reduction in the size of the spaces within the flats and their inconvenient layout.69 Soviet architects reduced living space to ensure that apartments were distributed to individual families; however, to offset the resulting increase in cost estimates, they minimised auxiliary spaces and simplified the layout.70 Distribution norms and cost limitations had shaped spatial arrangements and dimensions, not concerns about commodity, convenience, and usability.

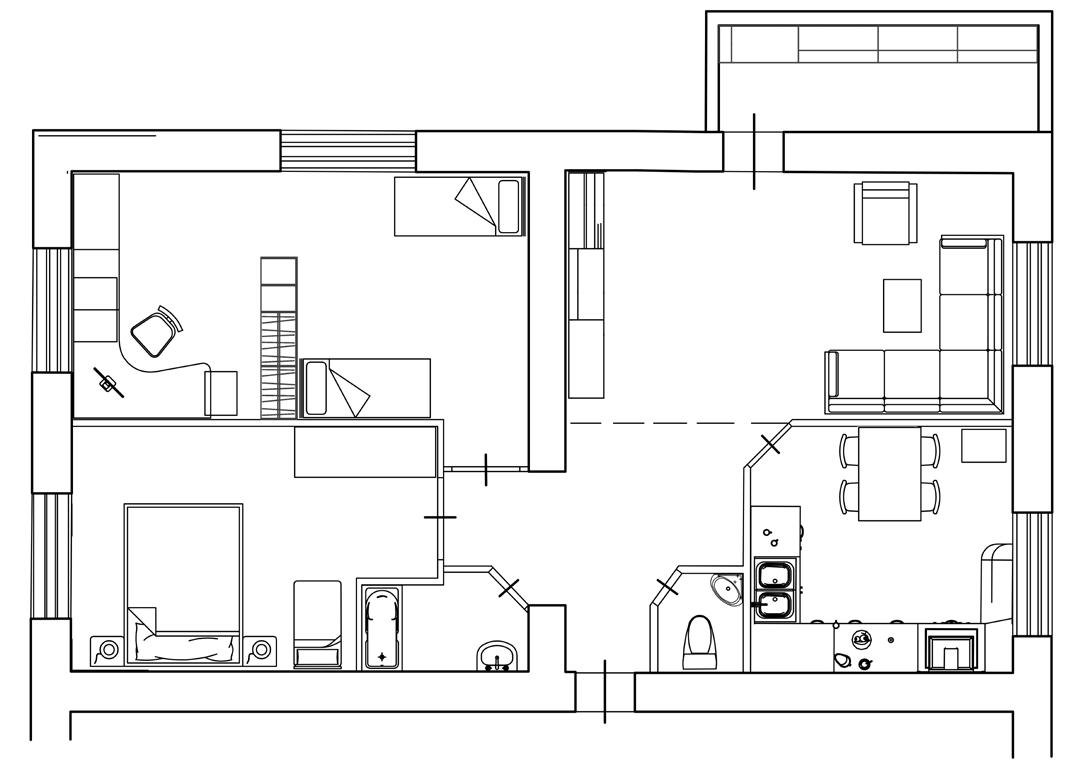

The initial prototype apartment designs created by housing authorities were based on rather primitive presumptions about family composition. Some even argued that eight prototype apartments at most could accommodate every possible family configuration. Although more layouts were later developed to accommodate various families, the lack of a market mechanism prevented serious consideration of the individual, family, and even group preferences in housing design and construction. 71 When designing the new layout for our apartment, my parents accounted for the eventual changes that would occur in our family over time and created a more flexible layout which could accommodate those. In this context, the biggest inconvenience presented the room without direct access to the corridor, which could only be accessed through the pass-through room. These interconnected rooms were a part of the strategy for maximising the efficient use of space, as they reduced the required corridor space, thereby decreasing the apartment’s total square footage and minimising costs.72 My parents decided to create a recessed corridor out of the existing doorway of the walk-through room, which allowed to make a separate entrance for each room (Fig.40). Eventually, as our family changed over time, we easily converted the rooms according to our wishes and needs (Fig.37, Fig.38, Fig.39).

68 Christine Varga-Harris, Stories of House and Home, p.6

69 Steven E. Harris, p.270

70 Ibid., p.82

71 Blair A. Ruble, pp.252-254

72 Mark B. Smith., p.126

Fig.37 - Initially implemented apartment layout after the redevelopment. My parents and I occupied the smaller bedroom, while my teenage brothers occupied the bigger one.

Fig.38 - Changed layout. A couple years after redevelopment my brothers had moved out I occupied their room.

Fig.39 - Current layout. When I was in high school me and my parents exchanged rooms, as I wanted a smaller bedroom and my father needed more space to work from home.

Soviet citizens did not have the privilege of redesigning their apartments, nor could they find flexibility in the existing standard layout to accommodate the changes in family life and structure. A.F.Timofeeva had lived in an apartment with two interconnected rooms for a year with her husband and two daughters, aged sixteen and twenty-two. When her elder daughter married and her son-in-law moved in, the question of who should live in the walk-through room arose. Seeing it as their right, the young ones demanded a separate room. Timofeeva, on the other hand, was not pleased. She was glad to receive new housing, but she desired peace and quiet in her old age, not a young couple passing by her and her husband’s room every day.73 While designing a limited number of standard layouts, architects did not consider marriages, divorces, births, and deaths - all of which occur naturally in every family. Central planning did not address the human concerns that were prominent in socialist ideology, nor did it provide housing flexibility and resilience. 74

The redesigned layout allowed our family to enjoy convenient and comfortable housing. Still, it would likely be impossible to implement it in the Soviet Union due to its cost and distribution unsuccessfulness. In order to estimate and compare the cost of 1 square metre of living space across designs, Soviet architects utilised various coefficients relating living space to auxiliary and non-apartment building spaces. K1, the coefficient of living area to the overall area, was used most frequently. By maintaining this coefficient as high as possible, architects could have reasonable assurance that their designs were cost-effective. 75 Our apartment’s original layout included 52 square metres of living space and 68.3 square metres of overall space. This results in K1 equal to 0.76. If we repeat the same calculation with the dimensions of the new layout, which are 47.7 square metres of living space and 73.8 square metres of total space, we obtain K1 equal to 0.64. The previous design was costefficient, while the new one, on the contrary, would make the apartment too expensive to be built under Khrushchev’s mass-housing campaign. Moreover, based on the distribution norm of 8.25 to 9 square meters of living space per person, the previous layout would allow to settle a family of six in the apartment, whereas the new layout limits this number to five. The State and its architects were put in a straightjacket by distribution standards and cost constraints, which dictated the designs. These principles were never reformed, making it impossible to make the changes necessary to ensure the residents’ comfort and the functionality of the khrushchevki.

73 Ibid., p.126

74 Blair A. Ruble, pp.252-254

75 Steven E. Harris, p.80

Kitchen: from “Rationality” to Comfort

No other unit of the separate apartment paid as much attention to integrating space in a rational system replete with the most recent amenities and appliances as the kitchen. Sinks, a stove and oven, a refrigerator, food preparation counters, a table and chairs, storage areas, cooking and eating equipment, a radiator, and even a washing machine for clothes all had to fit into a 5.5-square-meter space. The rationally organised kitchen resembled an assembly line, allowing the outside world’s scientific organisation to permeate and shape the new Soviet home. 76 Prior to the renovation, our apartment featured a similar six-square-meter “assembly line” in which realistically, only one person could cook or two people could dine at the table, given that the apartment, as previously stated, was inhabited by six people during Soviet times under the distribution norm. The Soviet State portrayed these tiny kitchens as ideal spaces in which small dimensions were actually advantageous and more practical. In reality, such a kitchen would appear highly inconvenient even for one person cooking, let alone accommodating all six people residing in the khrushchevka.

I recall my father saying we have such a large and spacious kitchen, but is a 10-square-meter space actually that generous for a family of five? It certainly isn’t until you compare it to the 6-square-meter one that was there before renovation. The 5- to 7-square-meter kitchen became an inseparable feature of the Soviet khrushchevka. The cartoon advertisement published by the State demonstrated that everything is proximate and rational in new 5.6 square meters of kitchen space. They claimed that 500 steps were required to prepare soup previously and that this extensive movement is now eliminated.77 The kitchen was even a site of Cold War ideological conflict in which the Soviet housewife’s mastery of rational living and restrained consumerism would prove the superiority of socialism over the grotesque excesses of irrational capitalist consumption.78 In reality, many residents were unsatisfied with the new small and functional kitchen. They compared it to a “matchbox” and argued that “the calculation is done incorrectly”.79 My parents refused to accept such inconvenience, so designing a new, more comfortable, and spacious kitchen became an essential part of the renovation. They expanded the kitchen at the expense of the bathroom, which was relocated to the opposite side of the entrance. Two people can now cook at the same time in the kitchen, and up to five people can eat comfortably. It also allows for the simultaneous preparation and consumption of food without crowding or disturbing other users. The new kitchen is unquestionably not as large or as spacious as my father described, but it is undeniably more user-friendly and convenient.

76 Steven E. Harris, pp.249-250

77 ‘Nikita Khrushchev. Golos iz

[Nikita materiali [Additional materials], Pervii kanal, 5 April 2010, 00:23:03

78 Steven E. Harris, p.29

79 Ibid., pp. 271-274

The housing program launched by Khrushchev has been both a “resounding success” and “a woeful failure.” 80 Khrushchev solved the housing question, but his solution was not about ensuring that people would live in pleasant and comfortable apartments in the present and future. Rather, it was about demonstrating that the USSR solved the problem quickly and convincing people through ideology that the way he did it was a pass to a better and most importantly communist life. Through the “situated knowledge” and experiences of ordinary Soviet citizens, this chapter revealed Khrushchev’s distorted depiction of housing reality, with contradictions between the State’s assurances that khrushchevka was a step towards communism and the actual state of housing life.81

80 Blair A. Ruble, p.256

81 Christine Varga-Harris, ‘Khrushchevka, kommunalka: sotsializm i povsednevnosti vo vremya “ottepeli”’, pp.160-166

Conclusion

Through this dissertation, Khrushchev’s mass-housing programme and its product, khrushchevka, were unfolded by the author within the context of a broader understanding of the relationship between architecture and politics based on two primary connections that position architecture as an embodiment of power and architecture as a resource for power. The first connection was discovered through the following Soviet regime events and actions:

(1) the State’s exclusive ownership of the housing stock as well as its management through the governmental established housing campaign, (2) the establishment of policy and state regulations shaping the direction and design of the khrushchevka, (3) the use of Bolsheviks’ initial revolutionary promise to end the housing shortage and improve the lives of ordinary people as a primary drive of the mass housing campaign, and (4) provision of housing on an egalitarian basis. The second connection represented by architecture as a resource of power was discovered through the following: (1) demonstration of socialism’s superiority over capitalism through the successful and rapid completion of the mass housing campaign, (2) utilisation of khrushchevka’s rational and efficient design to shape and reinforce the ideological consciousness of Soviet citizens, (3) use of housing to construct the communist way of life, and (4) manifestation of the communist way of life and rational approach to living to hide the downfalls and drawbacks of the khrushchevka’s design. According to these findings, khrushchevka and the mass housing campaign present the perfect examples of architecture and power dynamics.

Ordinary citizens’ understanding and perceptions of Khrushchev’s mass housing campaign were successfully integrated and analysed within the context of architecture and power relationships expressed through khrushchevka. Their dissatisfaction and complaints revealed the actual state of the constructed housing reality and the newly established domestic way of life. Personal encounter with the topic built through “situated knowledge” was incorporated into this context, demonstrating how Soviet State could have created an actually enjoyable and comfortable housing environment for citizens if it did not impose so many limitations and have as much power and control over it as it did. The embodied knowledge also revealed the state and influence of Khrushchev’s mass housing campaign in the modern capitalist world that emerged in post-Soviet Union republics after the dissolution of the USSR.

The dissertation investigated the architecture and power relationship through the research of academics who covered the theme in their works, presentation of the mass housing campaign in the media, photographic studies, opinions of ordinary Soviet citizens who inhabited khrushchevki, and personal encounter. In this way, the study positioned these various sources and ideas within them to form a comprehensive picture of the mass-housing programme, including its benefits and drawbacks, as well as its close relationship with Soviet politics and communist ideology.

The analysis and study presented in this dissertation contributed to the limited academic work related to Khrushchev’s mass-housing campaign and khrushchevka itself by filling the gaps within the existing research and enriching it with the new approach to analysing the question expressed through the methodology of “situated knowledge”. Furthermore, academics typically study the housing that emerged under Khrushchev’s rule only within the context of a broader topic concerning housing development in the USSR and modern Russia. This study focused solely on the khrushchevka, treating it as a separate phenomenon. Additionally, the research contributes to the interdisciplinary field of study concerning architecture and power relationships. Academics within the field tend to focus on monumental architecture to analyse the relationship, neglecting khrushchevka. This dissertation proved Khurshchev’s mass housing campaign’s ability to contribute to architecture and power relationship studies.

The most vital recommendation deriving from the research is to continue unfolding the mass-housing campaign, khrushchevka and their underlying principles and ideologies by expanding the study into other fields such as sociology and psychology. Furthermore, the methodology of “situated knowledge” can extend to the autotheoretical practice of writing, which can reveal a new perspective on the question. The final recommendation is to continue the analysis of the khrushchevka in the modern capitalist reality, briefly introduced in this dissertation. This can significantly contribute to the understanding of the remains of the Soviet past practices, including architecture, in the post-Soviet Union countries. This dissertation has hopefully opened a new, provocative, and intriguing perspective on Khrushchev’s mass housing campaign and khrushchevka, prompting academics to focus more on this phenomenon in their future works.

Bibliography

Benjamin, Walter, ‘Moscow’ (1927), in One Way Street (London: Verso, 1979)

Bulin, Dmitrii, Skol’ko eshio prostoiat “khrushchevki“ v Rosii? [How much longer will the “Khrushchevki” stay in Russia?] (2013) <https://www.bbc.com/russian/ society/2013/10/131004_russia_slums_khruschev> [Accessed 5 October 2022]

Crowley, David and Susan E Reid, Socialist Spaces: Sites of Everyday Life in Eastern Bloc (New York: Berg Pub Limited, 2002)

Filtzer, Donald, The Khrushchev Era: De-Stalinisation and the Limits of Reform in the USSR, 1953-1964, Studies in European History, (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1993)

Freschi, Federico, ‘Postapartheid Publics and the Politics of Ornament: Nationalism, Identity, and the Rhetoric of Community in the Decorative Program of the New Constitutional Court, Johannesburg.’ Africa Today, 54.2 (2007), 27–49 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/27666891>

[accessed 11 November 2022]

Haraway, Donna, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,’ in Feminist Studies, v.14, n.3. (Autumn, 1988)

Harris, Steven E., Communism on Tomorrow Street (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2013)

Ikonnikov, Andrei, Russian Architecture of the Soviet Period, trans. by Lev Lyapin (Moscow: Raduga Publishers, 1988)

Ilic, Melanie and Jeremy Smith, Soviet State and Society under Nikita Khrushchev (London: Routledge, 2009)

Ironiya sudby, ili S lyogkim parom! [The Irony of Fate, or Enjoy Your Bath!], dir. by Eldar Ryazanov (State Committee of Television and Radio Broadcasting of the Soviet Union, 1976) [Motion picture]

Klimas, Martynas, ‘Identical Apartments, Different Lives in Photos by a Romanian Artist’, Demilked, 2016 <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floors-identical-apartments-neighborsbogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 13 November 2022]

Kuprin, O., Byt – ne chastnoe delo [Everyday life is not a private matter] (Moscow: Gospolitzdat, 1959)

Lefebvre, Henri, The Production of Space, trans. by Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991)

Makisheva, Galina, Riscanovca – raion dlia bednih jiteley [Riscanovca – district for poor citizens] (2019) <https://bloknot-moldova.ru/news/kogda-to-ryshkanovka-byla-nishcheyokrainoy-stolits-1145982> [accessed 12 January 2023]

Martkovich, Izrail B. and others, Zhilishchnoe zakonodatel’stvo v SSSR i RSFSR [Housing legislation in USSR and RSFSR] (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo literatury po stroitel’stvu, 1965)

McCauley, Martin, Khrushchev and Khrushchevism (Basingstoke: Macmillan in association with the school of Slavonic and East European Studies University of London, 1987)

Meuser, Philipp and Dimitrij Zadorin, Towards a Typology of Soviet Mass Housing: Prefabrication in the USSR 1955-199, trans. by Clarice Knowles (Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2015)

Minkenberg, Michael, ed, Power and Architecture: The Construction of Capitals and the Politics of Space (New York: Berghahn Books, 2014)

Narodnoe khoziaistvo SSSR v 1967 [National economy of USSR in 1967] (Moscow: Statistika, 1968)

‘Nikita Khrushchev. Golos iz proshlogo’ [Nikita Khrushchev. Voice from the past], Dopolnitel’nie materiali [Additional materials], Pervii kanal, 5 April 2010, 00:23:03

Pereplanirovka khrushchevki: idei dlia vseh tipov kvartir i gotovie plani [Redesign of khrushchevka: ideas for all the types of apartments and complete plans] (2022)

<https://www.ivd.ru/stroitelstvo-i-remont/organizaciya-i-podgotovka/pereplanirovkahrushchevki-91832> [accessed 12 January 2023]

Postanovlenie Tsentral’nogo Komiteta KPSS i Soveta Ministrov SSSR ot 4 noiabria 1955 goda №1871 “Ob ustranenii izlishestv v proiektirovanii i stroitel’stve” [Decree of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Council of Ministers of the USSR of November 4, 1955 No. 1871 “On the elimination of excesses in design and construction”] (1955) <https://web.archive. org/web/20140716132943/http://sovarch.ru/postanovlenie55/> [accessed 12 January 2023]

‘Prazdnik stroitelej’ [Day of the Builder], Vechernii Leningrad [The Evening Leningrad], 10 August 1957

Ruble, Blair A., ‘From khrushcheby to korobki’, in Russian Housing in the Modern Age: Design and Social History, ed. by William Craft Brumfield and Blair A. Ruble (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1993)

Smith, Mark B., Property of Communists: The Urban Housing Program from Stalin to Khrushchev (Illinois: Norther Illinois University Press, 2010)

Studia proiektirovania i dizaina Kolizey [Planning and design studio “Colosseum”] (2023) <https://www.spd-kolizey.ru/uslugi/pereplanirovka_kvartir/khrushchevki/> [accessed 12 January 2023]

Udovicki-Selb, Danilo, Soviet Architectural Avant-Gardes Architecture and Stalin’s Revolution from Above (London ; New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020)

Vale, Lawrence J., Architecture, Power, and National Identity, 2nd ed.. (Oxon: Routledge, 2008) van der Post, Laurens, Journey into Russia (London: Penguin, 1971)

Varga-Harris, Christine, ‘Khrushchevka, kommunalka: sotsializm i povsednevnosti vo vremya “ottepeli”’ [Khrushchevka, communal apartment: socialism and everyday life during “thaw”], Modern History of Russia, 1 (2011)

Varga-Harris, Christine, Stories of House and Home Soviet Apartment Life during the Khrushchev Years (Ithaca; London: Cornell University Press, 2015)

Varlamov, Il’ia, Kak mi doshli do jizni takoi: khrushchevki [How did we get to this life: khrushchevki] (2019) <https://pikabu.ru/story/kak_myi_doshli_do_zhizni_takoy_ khrushchyovki_6598101> [accessed 10 January 2023]

Veroi i Pravdoi [By Truth and Faith] dir.by Andrei Smirnov (Kinostudiya MosFilm, 1979) [Motion picture]

Yaneva, Albena, Five Ways to Make Architecture Political : an Introduction to the Politics of Design Practice (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017)

List Of Figures And Tables

Cover page – Artwork by Zupagrafika <https://www.zupagrafika.com/shop-posters/praguejizni-mesto> [accessed 5 January 2023]

Figure 1 – Photograph of Nikita Khrushchev <https://lenta.ru/articles/2021/09/11/ khrushchev/> [accessed 19 December 2023]

Figure 2 – Two families of candy factory workers rent a corner in a room, 1920-1923

<https://russiainphoto.ru/search/photo/?index=2&paginate_page=1&page=1&query=% D0%B1%D1%8B%D1%82+%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%B1%D0%BE%D1%87%D0%B8 %D1%85> [accessed 19 December 2023]

Figure 3 – Tsentralny special settlement, general view of one of the barracks, 1933 <https:// russiainphoto.ru/search/photo/years-1926-1938/?index=6&query=%D0%B1%D0%B0%D 1%80%D0%B0%D0%BA&paginate_page=1&page=1> [accessed 19 December 2023]

Figure 4 - Destruction of Ukranian USSR city Kharkiv during World War II <https://hvylya. net/analytics/history/2010-05-08-22-08-35.html> [accessed 19 December 2023]

Figure 5 - Kitchen of a Stalinist communal apartment, postwar years <https://back-in-ussr. com/2016/11/pro-kommunalnye-kvartiry.html> [accessed 19 December 2023]

Figure 6 - Extract from the book Advices on housekeeping , ed. by R. V. Svetsova (Volgograd: Volgogradskoie Knizhnoie Izdatel’stvo, 1959) <https://issuu.com/98517886/ docs/______________________-_1959_____> [accessed 10 December 2023]

Figure 7 - Soviet agitational poster <https://philatelist.ru/product/stroit-bystro-deshevo-dobrotno-plakat-1960-g-razmer-57kh91-sm/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 8 – Soviet agitational poster <https://papik.pro/plakat/14933-stroitelnye-plakaty-31foto.html> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 9 - Plan of the I-335K housing block type, image scanned from Meuser, Philipp and Dimitrij Zadorin, Towards a Typology of Soviet Mass Housing: Prefabrication in the USSR 1955-199, trans. by Clarice Knowles (Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2015), p.210

Figure 10 - Scene from the movie Veroi i Pravdoi [By Truth and Faith] dir.by Andrei Smirnov (Kinostudiya MosFilm, 1979)

Figure 11 - The interior of the room in the new house <https://realty.rbc.ru/news/5927c8f69a7947b63c1888c4> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 12 - Across the Soviet Union (Mogilev, Vilnius, Minsk): the wide geographical scope of the Khrushchev-era housing programme, image scanned from Smith, Mark B., Property of Communists: The Urban Housing Program from Stalin to Khrushchev (Illinois: Norther Illinois University Press, 2010), pp.84-85

Figure 13 - Approximate nomenclature of the standard designs for Khrushchev’s housing campaign, image scanned from Meuser, Philipp and Dimitrij Zadorin, Towards a Typology of Soviet Mass Housing: Prefabrication in the USSR 1955-199, trans. by Clarice Knowles (Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2015), p.210

Figure 14 - Basic nomenclature of articles for I-464 housing block type, image scanned from Meuser, Philipp and Dimitrij Zadorin, Towards a Typology of Soviet Mass Housing: Prefabrication in the USSR 1955-199, trans. by Clarice Knowles (Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2015), p.210

Figure 15 - Construction of the large-panel khrushchevka <https://realty.rbc.ru/ news/58d512f29a7947e284344448> [accessed 19 December 2023]

Figure 16 - Standardised apartment plans for different family compositions, image scanned from Meuser, Philipp and Dimitrij Zadorin, Towards a Typology of Soviet Mass Housing: Prefabrication in the USSR 1955-199, trans. by Clarice Knowles (Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2015), p.210

Figure 17 – 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 18 - 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 19 - 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 20 - 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 21 - 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 22 – 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 23 – 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 24 - 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 25 – 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 26 – 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 27 - 10/1 project by Bogdan Garbovan <https://www.demilked.com/ten-floorsidentical-apartments-neighbors-bogdan-girbovan-romania/> [accessed 10 November 2023]

Figure 28 - Moscow’s Cheryomushki district <https://russiainphoto.ru/search/ photo/?index=8&query=%D1%87%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%BC%D1%83%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8&paginate_page=1&page=1> [accessed 19 December 2023]

Figure 29 – Housing block in Chisinau, Republic of Moldova, author’s own work

Figure 30 – Housing reality in Chisinau, Republic of Moldova, author’s own work