8 minute read

Interview with Susan Jack by MARIA JELEŃSKA & LARA DELMAGE

Some things get better; some things get worse. It’s not going away.

Advertisement

interviewed by LARA DELMAGE and MARIA JELEŃSKA

We spoke with Susan Jack, a remarkable woman who has been working for Glasgow Women’s Aid for 17 years as a training and development specialist. She details how the charity supports women and children who have suffered from domestic abuse, and we talk about the measures that could be taken in order to prevent abuse from happening in the future – an idea that isn’t readily explored as an option. Words she used over and over again during the course of the interview were ‘horrible’, ‘terrible’ and ‘shocking’. This was especially in regard to the disturbingly commonplace nature of sexual harassment that is a global problem; around 1 in 3 women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual abuse in their lifetime. In our lifetime.

Lara Delmage: For those who don’t know – what is Glasgow Women’s Aid?

Susan Jack: Glasgow Women’s Aid is a feminist organisation that provides information, support and temporary refuge accommodation for people experiencing domestic abuse. Within refuge there’s support for women and separate support for children and young people. We provide guidance for women who are moving on from refuge and there’s also outreach for those who aren’t in refuge. So there’s quite a range of different support here.

LD: I can imagine not everyone would like to go into refuge.

SJ: When the organisation started in 1973, the volunteers focussed on refuge accommodation. The more they worked with women, the more they realised that what they usually most wanted was somebody they could come and speak to; somebody who would listen to them and believe them. That is a huge part of what we do. Where you are just now is our public access office, and this is generally where women first come into contact with the service.

Maria Jeleńska: People often equate domestic abuse with physical violence, and you’ve mentioned before that this is just the top of the iceberg.

SJ: Until approximately in the 90s the focus was very much on physical abuse. They used to talk about ‘battered wives’ and now nobody uses that terminology anymore. From then onwards there has been much more recognition of emotional and psychological abuse and the really significant impact it has. Women will very commonly tell you that what really causes the long-term damage is name calling, criticism, intimidation. However, women will still use physical abuse as a bit of a benchmark, they’ll tell you the range of things that they’re living with, and then they’ll say ‘he’s never actually hit me though’. So I think that people still unfortunately have the idea that unless you’re being hit, is it abuse? And again, if somebody hits you, you know that they shouldn’t be doing it. Whereas other kinds of abuse are far subtler and quite insidious. People can be living with abuse and not even know it. The new legislation has very much put the focus on emotional and psychological abuse, which is a recognition of the significant damage that it can cause to the victims.

SJ: Absolutely. The criminal justice system, in my opinion, does not serve the needs of the victims very well. And again, that is why we need to raise people’s awareness. If workers are aware of the nature of emotional and psychological abuse, they’d be more likely to pick up on it and document it. That’s were evidence could actually be found. Fortunately, the Police now organise trainings on coercive control, so the investigation can be more appropriate.

MJ: Your experience shows that for the victims it takes already enormous strength to leave the abuser, and then even more to actually stay away from them. How long can this process take?

SJ: It can take years for women to come here, and also then they’re unlikely to leave their abuser immediately. Women will very often gather bits of information so they know what their options are. Very rarely women will leave and not go back to the perpetrator, and there are a whole range of valid reasons for that. Most importantly, it is difficult to switch off your emotions towards the person. Statistically, abuse usually starts after many years of the relationship. By that time, victims are already emotionally invested; sharing home and having children makes it very challenging to leave. Not everybody has family or friends who are able to accommodate them.

LD: Do you think a lot of women and girls don’t realise they are being abused?

SJ: Oh absolutely. I really think that if we’re ever going to try and deal with abuse effectively, we need to work with people from a young age, teaching them how to respect each other in relationships. That’s the only way you can try to stop it – and even that isn’t going to eradicate it. However, schools usually have problems with funding that kind of thing. Also, I do think the way girls and women are sexualised and the pressure that por

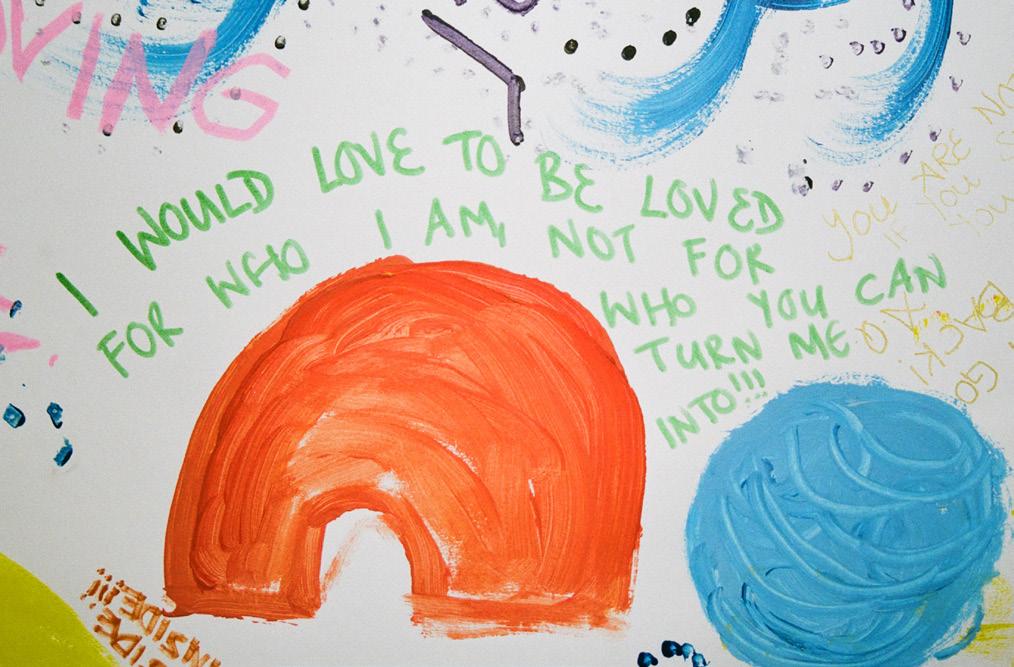

Extract from poster made by survivors of abuse at GWA’s quarters / photo Maria Jeleńska

LD: And with porn being your first experience of sex, especially really rough porn – can only build misconceptions and mistreatment of women and men in sex.

SJ: Yes! How does that impact you in your intimate relationships? How does it impact the women, or other men that you’re engaging with? I think it should be in some way regulated. I know now that they are looking at ways to try and do that, but the porn industry makes so much money. Nobody’s being a prude about sex. If people enjoy having consensual sex in a way that seems violent to others, it’s fine! But a lot of the focus in pornography seems to be about male pleasure, it can be very rough. Young men are engaging with that material at a very young age. There’s also a growing trend of women dying during sex. In the UK, two women a week (!) are murdered by their partner or ex-partner. This is shocking and completely unacceptable. Some of the cases may be coming from violent pornography. I remember watching feminist porn, and it’s completely different. You should have a look!

MJ: On the other hand, how can we look at the problem from a male perspective?

the way that they’re socialised. It’s all: “don’t cry”, “don’t show your emotions”, “you’ve got to be tough”. Again, you’ve got such a high rate of suicide among young men; the expectations and pressures embedded in boys from young age, widely described as toxic masculinity, is one of the reasons. We annually will do a seminar with social work students at the Caledonian University, and last year this young man bravely said “I’ve got great friends, but sometimes when we’re out somebody will make a rape joke. This makes me really uncomfortable but I don’t feel able to challenge it.” I can understand that, but if he did challenge it what he’d probably find is quite a lot of his other friends are uncomfortable too. I do understand that it’s hard for men too.

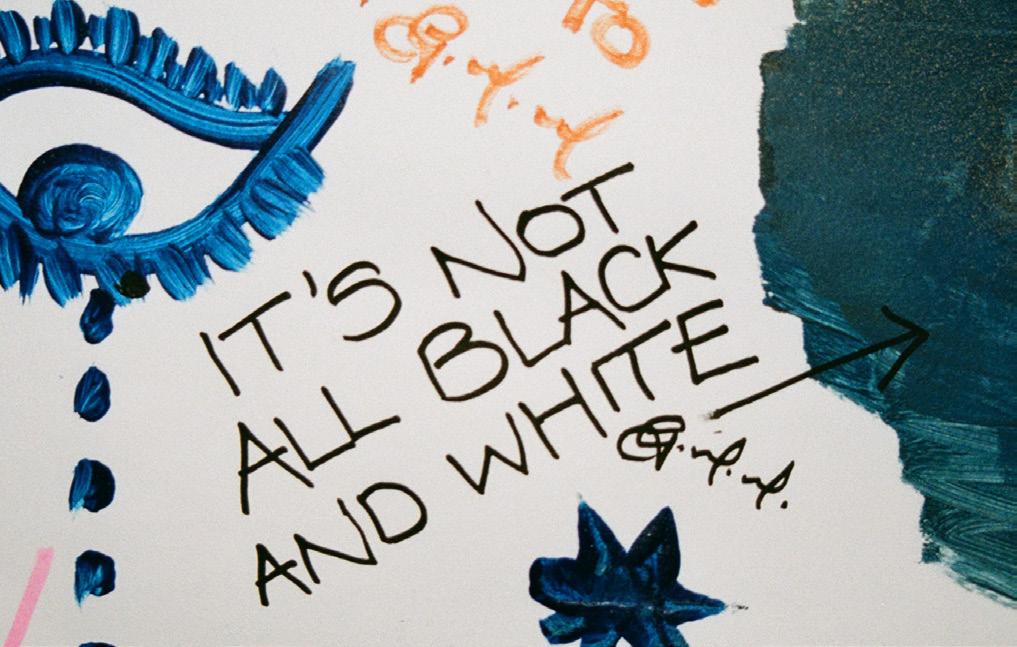

Extract from poster made by survivors of abuse at GWA’s quarters / photo Maria Jeleńska

MJ: What are the most common mental health implications of being abused, and are victims getting proper mental support?

SJ: Anxiety and depression. They’re more likely to self-harm, attempt suicide and develop drug, alcohol or other kinds of addiction. Becoming an addict happens for a reason and experiencing domestic abuse can be one of them. Mental health services throughout the whole country are experiencing severe resource shortages. One can wait months to see a psychologist and it’s shocking. What is promising is that young people are more willing to talk about mental health now. However, schools might have one counsellor which is not enough. The CAMHS team (child and adolescent mental health services) entry level for support is far higher than it should be. A lot of people are suffering and not getting any help, which is a real failure on the part of the government. Even at Rape Crisis, if one wants support – ongoing support – there will be a waiting list. It’s the same for our service. It’s not that long, but you’ll still wait, 6

MJ: How do children respond to being in refuge?

SJ: Coming into refuge is hard for anyone. However, our specialists will focus on organising a time here to be positive. The children’s team is incredibly dedicated, and it is fabulous to see people really progressing and moving on to a better place. Some children might need to move school, which is a massive life change for them, but sometimes that’s the safer thing to do because the perpetrator would know their previous school.

LD: Is victim blaming still common?

SJ: Yes. When it comes to abuse, it’s usually the women who have to leave, not their perpetrators. If you think about it – why? But that’s just a given. And I know that it’s been highlighted that there has been a number of sexual assaults around the University, and the discourse has been all addressed to the possible victims: “women take care”. We’re always the ones who have to protect ourselves, cover ourselves up and keep our heads down so that we don’t attract attention.

MJ: Me and my girlfriends would tell each other to be safe just before we go to the library around 6 pm, when it’s already getting dark. It is wrong on so many levels.

SJ: You should be angry about it! See if you asked a room of about 100 women if anything like that had happened to them, most of them would say yes because it’s so common, we’ve all had these experiences. Oh, you need to get angry!

Susan Jack / photo Maria Jeleńska