13 minute read

Healthcare infrastructure as “top priority” for women

from Strengthening Health, Community Resilience and Livelihoods in Donetsk and Luhansk. Gender analysis.

by mb.designer

elderly, who have no relatives, or whose relatives are on the other side — in Donetsk, in Yasynuvata (social worker, female, site 1)

“Shyness” of men in approaching humanitarian NGOs or in taking an active civic role, was perhaps the most recurrent theme in interviews and focus groups in this study . This “shyness” can be explained by gender stereotypes of men’s self-sufficiency that make it difficult for men to ask for help . As for active participation in civic life, men might feel “shy” lacking soft skills and social capital . Women are socialized to value social networks and empathize with others, so are more likely to engage in volunteering, community projects, etc . Women also see themselves as responsible for the household, so are more active in searching for humanitarian aid and other possible assistance . According to PAX report, women tend to reproduce such stereotypes themselves, by commenting that men are “psychologically weaker” while women are “stronger” and more “enduring” when dealing with paperwork and a need for queuing and visiting numerous institutions . Women have “authoritative” knowledge of survival practices (presented as traditionally “feminine” world of knowledge and authority) . This research concludes that “A man can be present in a situation of receiving and fighting for state assistance, the he finds humiliating, only in the role of “accompaniment” and “protection” of women – to intervene when he must “protect the woman” from bureaucratic abuse”9 .

Advertisement

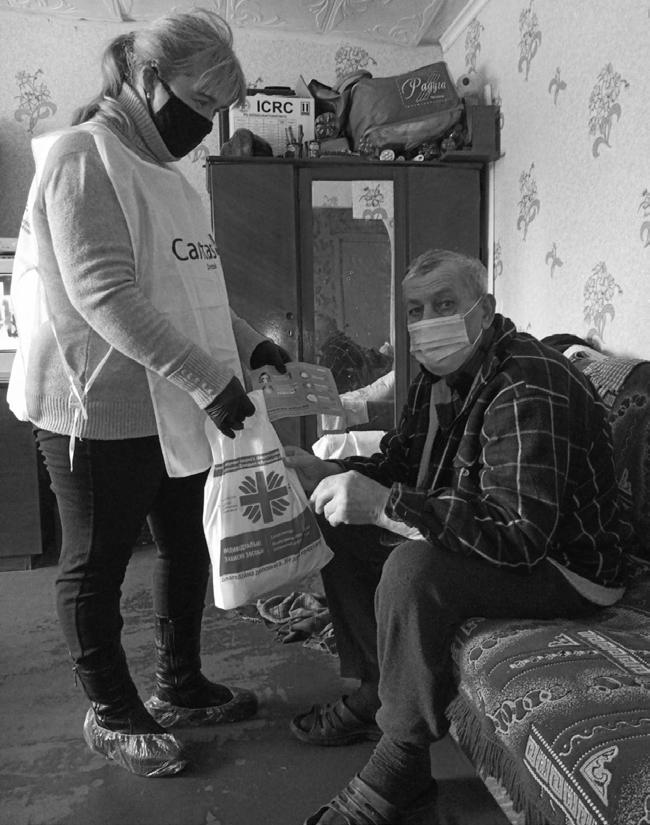

The all-Ukrainian survey of IDPs also revealed a higher percentage of female IDPs approaching all social and governmental structures, compared to their male counterparts . However, men are usually more successful in their communication with service providers and have fewer complaints on the quality of service . For instance, 56 .6% of men as opposed to 48 .5% of women in this survey successfully defended their rights in court . Women in this survey complained more about unclear guidelines for approaching governmental structures, compared to men: 15 .4% of women vs 13 .1% of men on the need to submit additional documents, 10 .1% vs 6 .6% on lack of information on the procedures and frequently asked questions, 6 .2% vs 3 .9% on delays in resolving their cases, 6 .5% vs 4 .3% on poor condition of waiting rooms and toilets, and 6 .5% vs 4 .9% on disrespectful treatment10 . It is difficult to say whether men indeed are more efficient when it comes to approaching governmental structures, or if women perceive the same situations in more dramatic tones, being socialized to express their emotions more easily than men . In any case, Caritas could offer consultations and accompaniment to its beneficiaries to make their approaching government structures more efficient . Creation of “mobile offices” would be welcome .

Rural and small town communities in Ukraine often lack basic social infrastructure, related in particular to healthcare needs of its population . This poses difficulties for reduced-mobility vulnerable groups in accessing healthcare services that they need in the vicinity of their homes . According to FAO report, unment needs for rural elderly are 47% for outpatient care, 81% for rehabilitative care through polyclinics, 71% for in-patient homecare, and 32% for emergendcy medical care . While men’s reasons for not visiting clinics were related to gender stereotypes, for women main reasons were infrastructural – closure of rural clinics

9 https://paxforpeace .nl/what-we-do/publications/changing-gender-dynamics-througharmed-conflict-in-ukraine (p .25) 10 http://gutszn .kr-admin .gov .ua/rivnist/gendernuy%20analiz .pdf

We need a space for mothers, who are sitting at home with children. Some kind of activities for mothers, so that they could come. Because I have friends - one mother with two children, another one with one child. They sit at home with these children all day long! There is no space to socialize, nowhere to go out. We don’t have such a place to hang out, just a normal place where we could sit… Where we could just drink some tea, just to go outside of your home.

Healthcare is one of the most acute needs identified by women in frontline communities, and any contribution towards “filling the gaps” is greatly valued . Among projects that beneficiaries appreciated were doctors’ visits to their rural clinics for check-ups (organized by “Doctors without borders”, “Red cross” etc), transport to visit clinics in neighbouring cities, free medication, purchase of medical equipment such as ultrasound or gynecological chair for their local rural clinics, and health check-ups at schools and places of work . Among doctors that were mentioned as lacking the most were paediatricians, dentists and gynecologists . Long distances to the nearest maternity ward is an acute problem for pregnant women, who may not be able to reach it quickly when labour begins, and who will not be able to count on the support of family members in the vicinity (one young mother mentioned that if distances were not so bi, she would have liked her husband to be with her during labour, and to have family members’ visits after giving birth, as family often buy needed medication and bring home-cooked food, clean linen and clothing to the hospital) .

The most covert dissatisfaction with healthcare infrastructure was observed in site 1 . Firstly, there are no pharmacies and it is a challenge to secure needed medication . Secondly, the hospital that serves two villages in our study is in Kostiantynivka and there is no direct public transport, so residents have to take a taxi at 600 UAH (20euro) one way . And most urgently, they complained about not being served by their family doctor, who is supposed to come with visits from Oleksandropil (former Rosivka), but comes very rarely (with the beginning of the pandemic does not come at all, asking patients to call or write in Viber) . While voicing their complaints, they asked numerous times whether “this information will not reach the authorities”, and it seemed that they were afraid of not being served by anyone at all, and having even the clinic close down completely .

Our clinic exists just on paper. Because our family doctor comes just once a week, and honestly speaking she may come, or may not come… With the beginning of the pandemic she doesn’t come at all. Oh, we do have a clinic but we belong to Rozivka clinic. But we can’t say this. Because then we won’t be served at all. She is there, but really she isn’t. We do have a clinic, but our doctor died. And we sent a young girl to study to become a doctor, but she received her education and moved to Kharkiv. Because there are no prospects here in our village.

— The problem of lack of medical personnel is addressed by various charitable NGOs. “Doctors without borders” offer by-monthly visits by gynecologist in Zolote-4, and “Doctors for peace” offer similar visits by gynecologist once a month in the building of “Shaktar” club. In Zolote-2 it is possible to make appointments once a month with military doctors. — Volunteers came, Doctors for peace also had consultations. They bring medicines, they ask about concerns, measure blood pressure, take blood tests for sugar levels. As they’re taking tests, they ask about concerns and issue medicines. They come regularly to Zolote-3, quite often. Everyone is pleased. Because our problem is that we have to go all the way to Severodonetsk, to Popasna, but here it’s all on the spot. Many people make use of this opportunity, it is free. And they immediately recommend it to others. — And how often do they come? — They don’t depend on us. They tell the patients when they will be coming. And as for us — they don’t keep any relationship with us. — So if you need to get an ultrasound, you would need to go to Lysychansk?

“Shyness” of men in approaching humanitarian NGOs or in taking an active civic role can be explained by gender stereotypes of men’s self-sufficiency that make it difficult for men to ask for help. As for active participation in civic life, men might feel “shy” lacking soft skills and social capital. Women are socialized to value social networks and empathize with others, so are more likely to engage in volunteering, community projects, etc. Women also see themselves as responsible for the household, so are more active in searching for humanitarian aid and other possible assistance.

— Yes. We don’t have our own doctor. Someone needs to get necessary training (to operate the ultrasound machine). But it’s OK, people go to Lysychansk. Before they used to go to Pervomaysk, its about 8km. Pervomaysk was closer, we were used to going there. But Lysychansk is quite far (nurse, site 2)

There are two ambulances in Zolote, but due to large distances it may be difficult to reach residents of Zolote-4, our case study . A similar problem arises with pharmacies – usually, only residents of the district where they are located, have access to pharmacies and ambulatory clinics . In some cases, residents prefer to travel to Hirske (at about 20km from Zolote) or Lysychansk (at 35-40km) . There is a private clinic in Lysychansk, but its services are unaffordable to vulnerable groups .

In this research, women tended to express more concern than men with the condition of healthcare facilities and lack of doctors, and spoke at greater length of cases where they encountered difficulties . Gendered use of healthcare facilities is documented by other research: scholars observe greater prophylactic care for one’s health among women, and greater need for hospitalisations and rehabilitation among men . Low accessibility of healthcare services (including poor public transport connections), a growing pressure on existing healthcare facilities, and a need to travel to neighboring regions (Kharkiv and Dnipro) for specialized consultations have all been previously reported by experts working in the region .

Lack of other social infrastructure may also pose challenges to livelihoods of vulnerable categories . Of particular concern is insufficient public transport network — a problem, highlighted by respondents numerous times at every occasion throughout the interviews and focus groups .

Bicycle use is common in all of the communities . Municipal social workers visit the elderly and people with disabilities on bicycles (bicycles are generally provided by the Territorial centres for the provision of social services) . Several social workers employed by Caritas also expressed a desire to obtain a bicycle, which in their view is needed in particular with carrying groceries from the shops to beneficiaries homes . Small grants to purchase electric bikes and scooters, could significantly improve mobility in communities “cut off” from transport networks, at least for shortterm trips to nearby towns within cycling distance .

Some social infrastructure is created privately, but there is lack of information on living conditions, fees, and accordance of such facilities with current regulations (such as fire safety, which has become a concern after several fires in overcrowded private retirement homes that took lives of their elderly residents) . For instance, one such retirement home was built in Valuyske and currently accommodates between 56 and 60 people (“It is overcrowded, and we have nowhere to accommodate our pensioners. There are many who would like to live in a retirement home, because now it’s warm, but in winter with heating costs, gas — it’s too expensive and the subsidy is not enough”) .

A social worker from site 2 also identified an acute lack of retirement homes for the single elderly . She described at length the case of one of her beneficiaries, who has memory loss, lacks water in her house, and had distant relatives take away her pension without providing any kind of care . This social worker approached a deputy from local council, but to no avail . She felt obliged to support this beneficiary by cooking her food and even bringing water from her own home, until finally she found

Women tended to express more concern than men with the condition of healthcare facilities and lack of doctors, and spoke at greater length of cases where they encountered difficulties. Scholars observe greater prophylactic care for one’s health among women, and greater need for hospitalisations and rehabilitation among men.

In all three of our locations, poor public transport, high price of tickets, and unsatisfactory condition of roads, has a negative impact on women’s ability to access basic social infrastructure . Interviewed men seemed unaware of the daily difficulties their wives, sisters and mothers face, and a common response was “distances aren’t a problem, as long as we have money” . This could also be linked to the fact, that men can rely on private transport more than women, who rarely own private vehicles — around a quarter of rural households in Ukraine own cars, but only three percent of rural women reported owning a private vehicle (FAO, 2020, p .54) .

Need to rely on public transport means that women may not have enough time to solve all their questions in one visit (as office hours don’t necessarily match public transport schedules), or on the contrary, are forced to waste time waiting to be served . For instance, Zolote does not have social protection services, and residents need to contact social protection department in Popasna at about 30km . Residents complain that since there is no prior registration for a specific time, people just come and await their turn in line, and may not be able to see a social worker / consultant on the day of their visit . (This could be one of the reasons why some people who qualify for social aid do not receive it) . One possible area of intervention by Caritas could be in training social workers and more active beneficiaries to use municipal e-services, as well as setting up mobile consultation points locally (in rural council buildings, libraries or schools) .

Among other infrastructural needs, mentioned in interviews and focus-groups, were problems of obtaining pensions and other social payments in remote rural areas, especially by reduced-mobility beneficiaries, most of whom are women (as life expectancy is higher by ten years for women than for men) . Many of them receive social payments on their banking cards, but lack a possibility to withdraw funds, thus being forced to lend their cards and share pin-codes with neighbours who are heading off to cities, asking to withdraw money on their behalf . Even in the administrative centre of site 1 — the town of Ocheretyno — there were until last year no ATM machines . The need for ATMs was identified by UN women project mobilizers, and as a result two ATMs were successfully installed — which could be seen as a positive case of infrastructural intervention, to be taken into consideration in other sites (“we used to have a small problem — we had one pharmacy, but no ATM. But this problem is now resolves, we had to ATMs installed. Before we had to travel to another town to withdraw money” — single mother, IDP, site 1)

Furthermore, council representative from Vilkhove (site 3), informed us that as of 1 September 2021 post offices will stop distributing pensions in villages . Most pensioners will be forced to turn to banks, but there are no banks in rural areas . This council representative also mentioned two hamlets of Syze and Bolotiane where only a dozen pensioners remain and there is absolutely no transport or infrastructure there .

Even in cases where infrastructure requires repair works, and opening hours are reduced due to lack of funds, residents nonetheless tend to describe positively they role of social and educational infrastructure in their communities and the work of teachers and social workers . In all interviews, where the interviewer asked about available infrastructure, they began their account with schools and clinics, and for many such infrastructure seemed to be a proof that “our village is still alive” . The “human capital” and respect that female workers in education, healthcare and

In all three of our locations, poor public transport, high price of tickets, and unsatisfactory condition of roads, has a negative impact on women’s ability to access basic social infrastructure. Interviewed men seemed unaware of the daily difficulties their wives, sisters and mothers face, and a common response was “distances aren’t a problem, as long as we have money”

The “human capital” and respect that female workers in education, healthcare and social protection enjoy in their rural communities, is an important asset to build upon for humanitarian NGOs. Workers in the “social sector” are also often more vocal, active in public life, and responsive to innovative proposals.