4 minute read

How royals broke rules in the 18th century

Noé Vagner-Clévenot (History, 2021) is a DPhil candidate specialising in political, gender and cultural history. His interests lie in the agency of princes in the self-fashioning of their image. Here, Noé outlines his thesis.

One question DPhil students get asked a lot is: ‘why does your thesis topic matter?’ Personally, I struggled at first to provide a satisfying answer to non-historians, especially as history is a discipline whose research outcomes have a less concrete impact on people’s lives than, say, molecular research. Nevertheless, history is invaluable, reminding us of where we come from and providing numerous insights into modern society. My DPhil research focuses on a prince who had to overcome gender barriers, tackle ceremonial challenges and spread a positive image of himself long before the advent of social media, in the 18th century.

In 1736, Francis Stephen, a prince from Lorraine (today in north-eastern France), married Maria Theresa of Austria, the daughter of Charles VI. As King, Charles ruled dominions spanning across Europe (including Austria and Hungary). As Holy Roman Emperor, he was also the theoretical head of a confederation encompassing, broadly speaking, Germany, Austria and northern Italy. Maria Theresa was supposed to inherit the dominions, but she could not become Empress – the Empire was an elective monarchy, and only a man could be elected. Therefore, Francis was her family’s only hope of keeping the imperial crown.

Four years later, in 1740, Charles VI died. France, Prussia and Bavaria invaded Maria Theresa’s new territories. After Charles’ death, Francis held an unprecedented position. Husbands, in Christian couples of the 18th century, were expected to hold seniority. But although Maria Theresa became Queen, Francis did not inherit the title of King. This fundamental contradiction between gender and social hierarchies had enormous implications.

On the one hand, while it was not shocking for a woman to occupy a man’s position, it was impossible for Francis simply to hold the role of a queen, as it would seriously undermine his masculinity. On the other hand, Maria Theresa theoretically held the senior rank, which she needed to assert. In the 18th century, rank conditioned the way all members of society presented themselves. Protocol rules ensured that everyone’s status was clearly visible. Even today, there are echoes of this convention. Although most countries in the world are now republics, when they host a state visit an ostensibly monarchical ceremonial is followed, whether the visitor is a monarch or a president.

To show that Maria Theresa was the Queen, between 1740 and 1745 (the date of Francis’s eventual election as Holy Roman Emperor), the royal couple reinvented the public representation of the ruling sovereign and the consort. In doing so, they partially de-genderised their respective roles. Before Maria Theresa’s time, a ruling couple was perceived as a sovereign entity. But by clearly emphasising Maria Theresa as the ruling monarch and himself as the consort, Francis contributed to the gradual embodiment of sovereign authority in the single figure of the monarch.

Being socially inferior to his wife was a concern for Francis. He wished to be elected as Holy Roman Emperor, but being seen as a consort by ministers, diplomats and the Viennese people was detrimental to his public image. To address this, Maria Theresa named Francis ‘co-ruler’, which made him a major actor in government. For instance, new ministers and public servants then had to swear their loyalty oaths to both members of the couple. Furthermore, there were many occasions where the royal couple did not swap their gendered position. In some public events, Francis was placed on an equal footing with Maria Theresa and occasionally outranked her – which broke protocol rules and set a new precedent. Already in the 18th century, seemingly rigid rules could be transgressed to serve geopolitical interests – a phenomenon still evident today.

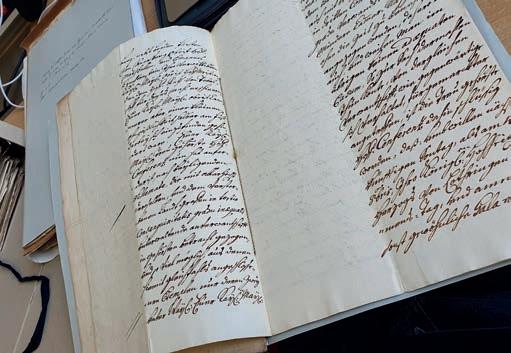

These changes were not only visible to ministers and diplomats in Vienna, but also to a wider public. Maria Theresa and Francis were eager to spread both their individual images and a joint image as a couple in their propaganda, which consisted of printed poems, engravings and medals. These were distributed to multiple parts of the Habsburg monarchy, even reaching distant regions such as Brussels, where I found many engravings in the Royal Library. By taking such care over their image, Maria Theresa and Francis struck a subtle balance between stressing the former’s royal dignity and portraying the latter as a competent prince – an early multimedia campaign, incomparable in scale to those we are now subjected to, but not so different in nature.