19 minute read

business

young baker who with his wife operates Brazen Baking in Camden and had accompanied me to The County—“they don’t eat chips anymore.”

I got the point. National potato consumption has declined in recent decades, although potatoes remain the number one vegetable consumed by Americans. For this and other reasons, potatoes are no longer the unchallenged mainstay of The County’s wealth. While no one would abandon the crop entirely, it’s time to look at productive alternatives, such as organic grains. But potatoes will always be important, admits Dyer, who works for the Potato Board developing crops for diversifying Aroostook potato farms.

Advertisement

Another advance in the Aroostook grain game is taking place in Mapleton, just west of Presque Isle, where the Buck brothers, Jake, Josh, and Jaret, are pioneering their Maine Malt House enterprise, processing barley into high-quality malt for the scores of sprightly breweries mushrooming in Maine. Malting is a complicated process that makes you wonder how beer was invented. First, grain is steeped in water to soak, then spread in a thick layer to germinate: the germination is stopped by heating and drying in a kiln. Enzymatic activity increases the sugar in the grain, lending sweetness to the beer and giving the yeast something to feed on.

Not every brewery uses local malts, but a growing number tout Maine-grown ingredients. Vaunted Allagash, Oxbow, and Rising Tide are among a good 20 breweries setting the pace for using Maine-grown grains, malts, and hops. Allagash brewmaster Jason Perkins is especially proud of “16 Counties,” a creamy, flavorful ale that boasts entirely Maine ingredients, including Maine-grown organic hops. Oxbow uses the Maine Malt House product in its forthcoming “Domestic” farmhouse IPA, and has a 100% local beer spontaneously fermenting for two-plus years underway, made of all Buck Farm, Maine Grains and Alna Hops-sourced ingredients.

But while Oxbow is experimenting with Maine malts and grains, the brewery still sources most of its malt from France and Germany. “We’re working towards using more and more Maine grains—and malts,” Tim Adams, co-founder and

Left Spelt in the auger. Spelt is an ancient wheat that is naturally lower in gluten. Right Sara Williams Flewelling behind the wheel of a swather, cutting buckwheat into windrows so the grain can dry down in the field prior to being picked up for processing.

FOOD

Mt. Katahdin rises above fields of oats at Benedicta Grain Co. In 1987, as the town's population dipped to around 200 residents, Benedicta surrendered its plantation status and became an unorganized township.

head brewer at Oxbow, told me—a statement that holds true for many other breweries as well.

About a quarter of the Bucks’ 1,000 acres is planted to barley; the next step will be hop vines, another critical element in beer-making. “The potato market is mature,” Jake Buck explained as we toured the malt house. Like Qualey and Dyer, the Buck brothers are diversifying from total reliance on potatoes. “We count on working with local farmers to spread the risks around,” Jake said. But they could do a lot more, he admitted. Right now, despite producing 240 tons of malt annually, they can’t keep up with in-state demand. And with just two maltsters in Maine (the Bucks’ place in Mapleton and Blue Ox Malthouse in Lisbon Falls), there’s room to grow.

Allagash’s Perkins cites a statistic from the University of Maine at Presque Isle: there are 18,000 acres of fallow or idle agricultural lands between Presque Isle and Caribou, all suited to grain cultivation. In fact, Aroostook farmers have grown grains for a very long time, but almost always in rotation with potatoes (sometimes legumes, too). Such crops are either turned under as green manure or sold as low-value feed for chickens, pigs and cattle. What’s new in recent years is the focus on food-grade (as opposed to feed-grade) grains.

In the last decade or so, Maine has been fortunate to see an explosion of artisanal bread- and beer-crafting. We’ve come a long way since enriched sliced white breads (the Cushman’s and Nissen’s of my Camden childhood) and Haffenreffer and Narragansett fizzy brews. As of last winter, Maine had about 85 craft breweries, members of the Maine Brewers Association, and an estimated 51 craft bakeries, according to the Maine Grain Alliance, producing densely-grained, whole-meal loaves, often from wood-fired ovens, like the superbly nutty rye bread made with Aurora’s rye by Tim Semler at Tinder Hearth in Brooksville or the variety of breads and pastries at Standard Baking in Portland where, under Alison Pray’s direction in 2016, they used some 47,600 pounds of local wheat, oats, rye, cornmeal, and spelt, which represents 15% of their total grain use; and the number is climbing annually.

So why aren’t all of Maine’s brewers and bakers

Sara, Marcus, and baby Annabelle in a field of Japanese buckwheat. Aurora is working with Takahiro Sato, chef/owner of Yosaku in Portland, to develop a soba noodle made with Maine buckwheat. The noodles will be available in his restaurant this summer. Top Inspecting hops outside Maine Malt House in Mapleton. As the stalwart potato market continues to mature, young farmers like the Buck brothers are looking for ways to diversify, and Maine's booming craft beer industry offers new market opportunities. Bottom Jake Buck checks the “chitted” barley on the malting floor at Maine Malt House. The Aroostook County malt house is one of just two malt houses in Maine helping to bring locally-grown grains to Maine brewers.

using Maine-grown grains? The answer is complex, but it boils down to three factors: 1) capacity, 2) consistency, and 3) price. On that last point, flour from the Skowhegan mill, says Camden baker Jeff Dec, is double the price of King Arthur flour—“and they’re really giving a good price to farmers.” Making grain profitable for farmers is obviously an important piece of the equation, but when bakers and brewers, who operate on similarly slim margins, can get good-quality flour, or malted barley, for half the price, it’s hard to argue with the choice. Still, bakers like Dec, Semler, Pray, and many others acknowledge their customers recognize the value in locally grown grain.

As far as consistency, moisture in the grain is a key factor. Wheat, for instance, harvested at 18% moisture, must be dried down to 12 to 14% for safe storage. Otherwise, the grain starts to sprout, leading to the development of amylase, an enzyme that is undesirable, especially for baking. Grain high in amylase produces sticky bread; too low, on the other hand, and the bread will be unacceptably dry. “Variations in protein levels are just the nature of small-scale milling,” says Jim Amaral, who established Borealis Breads (then known as Bodacious) back in 1993. Larger-scale millers can blend various flours to a steady consistency to satisfy bakers’ needs, but the scale of grain growing in Maine, he said, has not yet arrived at that point.

Black Crow Bakery in Litchfield, turning out some of the most stunning bread in Maine over the last 25 years, uses some Maine grains but consistency crops up in any conversation with baker Mark Mickalide. Mickalide is unusual because he himself grinds the flours he uses. The biggest problem is what he calls bitterness in Maine-grown grains: “It doesn’t ripen to a real strong sweetness,” he said, adding that to get the flavor he wants, he blends, in equal quantities, Maine-grown grains with sweeter wheat from the High Plains and ordinary unbleached white flour.

Blending, then, is an issue of capacity. Yes, Maine could grow a lot more grain to supply the needs of both brewers and bakers—and it might well lead to greater possibilities for millers to blend flours. But reaching that capacity is not a quick process, especially not for organic grains, which are what bakers require.

Anyone involved in this revival of Maine grain growing agrees the movement began with Aurora’s modest Matt Williams, in symbiotic relationship with Borealis’ Jim Amaral. Amaral first got Williams involved in grains on a commercial scale. In the late 1990s with Borealis Bread a success, Amaral decided to enhance his line with a Maine-grown product. “I kept asking, why aren’t we growing wheat in Maine?” Amaral recalled. Williams, who was then the Aroostook County Extension Service specialist in small grains, had been experimenting with grains in rotation on his Linneus farm. As Amaral pushed, Williams planted, first, a crop of hard red winter wheat harvested in 1998. With no milling capacity in Maine, the grain was trucked across the border to New Brunswick. That continued until the border crossing became difficult after September 2001, at which point Williams added a grist mill to his grain operation.

Amaral now uses Aurora wheat for all his sourdough starters, but he is particularly proud of “Aroostook,” a grainy loaf made 100% from Maine grains, mostly wheat, and mostly from Aurora. Coincidentally, on the day I watched Matt Williams harvest oats, I caught up with Amaral, there at Aurora to take pictures for his new cookbook celebrating 25 years of Borealis. “When you’re making bread, you’re basically working with just four ingredients,” Amaral told me, “flour, water, yeast and salt. So it’s important to understand where each of these is coming from.”

Nor can you talk about grain in Maine without mentioning Amber Lambke and her vision of a “regenerative economy” for Central Maine. In 2012, she co-established the Maine Grains mill in Skowhegan in the old Somerset County jail, where Qualey Farms in Benedicta is among some 24 growers sending their grains in for processing. Maine has just two commercial stone grist mills, in Skowhegan and the one at Aurora. For a decade, Lambke, with a number of like-minded confederates, organized the annual summer Kneading Conference in Skowhegan. What the Common Ground Country Fair is for Maine’s organic farmers, the Kneading Conference has become for Maine’s grain farmers, brewers and bakers.

The Kneading Conference spurred the Maine Grain Alliance, now headed by Tristan Noyes, another young Aroostook native who, with his

Sara Williams Flewelling holds a prized French heritage wheat, ‘Rouge De Bordeaux,’ known for its excellent baking quality and superior flavor. Over the past few years Aurora has been restoring the grain seed to marketable quantities and expects to have it available to customers this fall. Maine bakers like Jim Amaral of Borealis have paved the way for more local grain production. While working with local flour can be less predictable than the standard King Arthur, bakers and eaters are enthusiastic about using Maine grains in breads and baked goods.

brother on the family farm in Woodland, is experimenting with several grains, including Sirvinta, a hard winter wheat from Estonia whose potential has a lot of Maine growers excited.

Noyes is equally enthusiastic about a new project for the Maine Grain Alliance, an 8-month feasibility study to look at creating drying, storing, and sorting facilities in four separate Aroostook County locations. This will take the onus off the shoulders of individual farms and farmers, and incidentally take a lot of the guesswork out of grain production.

Here in Aroostook (as in other parts of rural Maine) local and farm-to-table are not just fancy terms to sprinkle on chic restaurant menus. Local means community and an inter-connected economy. But there is still not enough local grain being grown and milled to serve Maine’s needs. I think of those 18,000 fallow acres up in The County where the climate is so good for grains— cool nights make sweeter wheat—and where taller varieties with better flavor and better baking quality can be grown. “Our biggest challenge is simply getting more land in production,” Matt Williams noted. “And it’s been the challenge from day one.”

nancy harmon jenkins is a veteran food writer and Mediterranean cookbook author who co-founded MFT’s Maine Fare celebration. | nancyharmonjenkins.com

young dairy

PHOTOGRAPHS BY JENNY NELSON

TEXT BY ELLEN SABINA

in many ways, dairy farms are a cornerstone of Maine’s farming community. Dairy farmers steward large tracts of farmland for feed and forage, while supporting the equipment retailers, feed stores, large animal vets, and other agricultural services that all Maine farms rely upon. Yet, while there are indicators that farming in Maine is growing, Maine's commercial dairy industry has not seen the same kind of growth. The number of midsized dairy farms has steadily decreased over the past few decades, as has the number of acres of farmland managed by dairy farms, due to the high cost of production, infrastructure, and the volatility of the milk market. The average age of Maine's dairy farmers is 54, and within the next decade, many will be reaching retirement age. At the same time, very few young farmers are choosing to go into dairy farming, deterred by the unpredictable price of milk and the high start-up costs inherent in the land base and infrastructure needed to establish a successful dairy farm. Without young dairy farmers, what will happen to all of the land currently in dairy, and to the infrastructure and communities that Maine’s dairy farms support?

The few young farmers who are bucking the trend and have decided either to become first-generation dairy farmers or to continue their family’s farm have a vital role to play in ensuring that dairy farms remain a foundational piece of Maine’s farm and food system. These are some of those farmers.

the milkhouse

SOUTH MONMOUTH

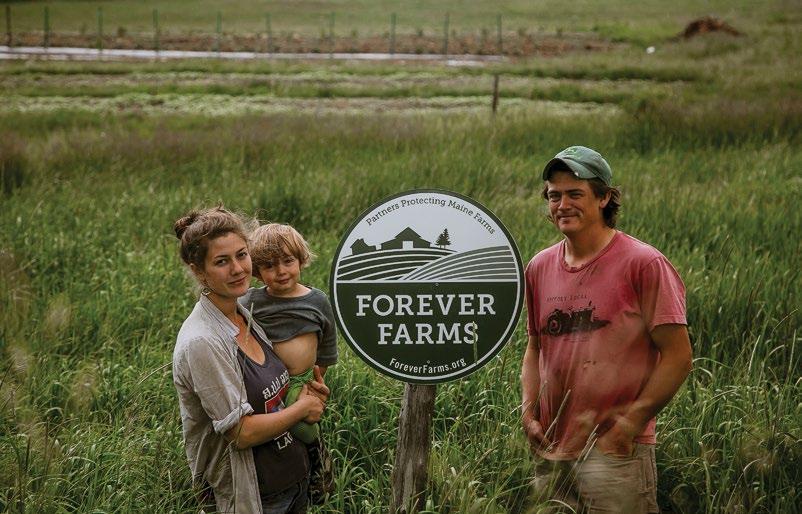

Caitlin Frame, Andy Smith, with son Linus, first-generation dairy farmers

For Caitlin and Andy, producing good food “is extremely gratifying work. It’s amazing to think of all the people who are nourished by what we produce on our farm. All that milk, meat, yogurt —that incredibly rich, nourishing animal protein—starts with just sun, soil, grass, and water, and we get to be part of stewarding it.”

Caitlin and Andy feel fortunate to be able to pursue their dairy farming dreams. The support of organizations like Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association and Maine Farmland Trust helped them access education, and eventually, a farm of their own. When they think about the future dairy farms in Maine, their hope is that “small and midsize dairy farms can become profitable again…we’re counting on it. And we’re counting on organizations like MFT to make the large land base necessary for such operations accessible.”

35 36

santy dairy

SKOWHEGAN

Brad Santy, second-generation dairy farmer

When he looks ahead to the future of his farm, Brad Santy is hopeful. He feels good about the decision to be an organic dairy farmer, and thinks that will help put the farm in a better position for his kids, who he hopes will want to take over someday. “It’s tough to start a farm with such huge overhead involved—land, infrastructure, equipment, and a herd,” said Brad. “It’s incredibly hard to start small, too, with one tractor and 10 cows. I don’t really know anyone who started a dairy farm from scratch without taking on an enormous amount of debt.”

Taking over an established family farm may be a bit easier than starting from scratch, but dairy farming will always be challenging. Equipment is expensive, milk prices go up and down, and access to enough land for pasture and feed is often a concern. And yet, if you love dairy farming as much as Brad Santy does, the decision to take on those challenges is an easy one. As Brad’s tattoo reads: “Farm on.”

fletcher farm

PITTSFIELD

Austin and Walter Fletcher, fifth- and fourth-generation dairy farmers, respectively

Though Austin Fletcher grew up on his family’s dairy farm, he wasn’t always sure farming was what he wanted to do for a living. “There was a time in high school when I definitely wanted nothing to do with it,” he said. “I didn’t hate it, but I didn’t think I wanted to do it.” But after leaving Maine and working other jobs and on other farms, Austin felt the pull back to his roots.

At 33, he’s happy to be back in Pittsfield, working alongside his dad, and preparing to continue the family business. The plan is for Austin to take over the farm gradually as Walter transitions away from farming full-time. “There is a personal satisfaction,” said Walter, “a sense of accomplishment, when your children look at what you have done and see something worthwhile. And when one of them says, ‘I see what you’ve done and I would like to be a part of it, to build on it and carry it forward,’ it is the greatest compliment that I could receive. It makes me very proud.”

39 40

bo lait farm

WASHINGTON

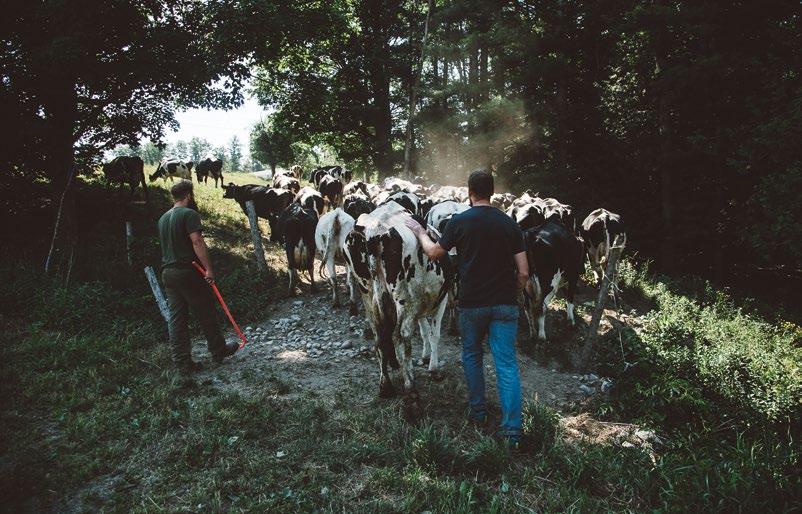

Conor and Alexis Macdonald, first-generation dairy farmers

While neither Conor nor Alexis grew up on dairy farms, they both “really love cows and love working with large animals, so we wanted to start a business doing just that,” said Alexis. “So many of our friends and family tell us they never would have thought we’d have become dairy farmers, but it seems to embody so many of the things that are important to us: animals, nature, hard work, community. It can be exhausting and maddening and frustrating at times, but it’s also empowering and rewarding.”

While their decision to become dairy farmers was relatively easy, being dairy farmers is anything but. Without a background in dairy farming, their learning curve has been steep, and making it work is a constant challenge. “There’s so much to know when you’re running a farm. You’re a vet, plumber, carpenter, accountant, manager, electrician, mechanic … the list goes on. Most dairy farmers we know still claim to have only learned the tip of the iceberg, even with decades of experience under their belts. It’s no exaggeration to say we learn something new every day, whether we want to or not.”

welch farm - & moon hill farm

In blueberry country, two farms hand the rake to the next generation

BY REBECCA GOLDFINE

PHOTOGRAPHS BY SEAN ALONZO HARRIS

Blueberry season brings traffic to the remote barrens of Down East Washington County, and to Helen’s Restaurant, a Machias mainstay since 1950. At Helen’s, guests line up at the counter for the signature whipped cream-topped pie filled with a quart-and-a-half of fresh, uncooked berries. The berries in their nationally-famous pie are all tended to sweet plumpness from nearby Welch Farm’s foggy perch in Roque Bluffs. “Out by the ocean, the berries taste better,” Helen’s owner Julie Barker says of the hand-raked product Welch Farm delivers daily to the restaurant, in season. “They are always free of sticks and leaves, and never soggy.”

Washington County farms like Welch and nearby Moon Hill Farm constitute the mom-and-pop backbone of Maine's 500 blueberry farms and are working to transfer their enterprises to the next generation in an era of consolidation and depressed blueberry contract prices. Father-daughter duo Lisa and Wayne Hanscom run Welch Farm with help from relatives, including Wayne’s ex-mother-in-law. Their family has held the farm since 1912, when Wayne’s grandfather, Frank Welch, bought 1,000 acres. Frank initially raised livestock and grew grains. By the late 1920s, he had turned primarily to blueberries—like lobster, once undervalued as commonplace—marketing his crop as “fog-nourished Bluff Point berries.”

Diversification has been critical to saving the farm. The Hanscoms are eagerly introducing agritourism and selling more “fresh pack” berries direct from their farm stand. Lisa and Wayne’s bond translates to a well-balanced business. When Lisa first suggested building tourist cabins on their land, Wayne was skeptical. When she proposed

offering farm tours, he asked, “Why? Who would come?” But when a tour bus pulls in today, visitors enthusiastically pour out. And there is a further commercial side—after giving a farm tour, Lisa offers her berries and unbranded homemade jams for sale.

Welch Farm’s fresh-pack yield is still small— constituting just 12,000 of the farm's total yield of 98,000 pounds in 2015—and Wayne plans to expand it. Instead of selling all their machine-harvested berries to frozen processors for only 38 cents a pound, Welch sets aside two to three acres to “spot rake” and sell directly for $5 a quart (1.5 pounds).

Due to financially-necessary waterfront land sales, Welch Farm has been whittled down to 340 acres. “I don’t want our farm to get any smaller,” Lisa stresses.

Lisa has always been Wayne’s obvious heir-apparent. Young Wayne was the same way when he trailed his grandfather Frank Welch around the farm making it clear Frank could pass it down with confidence. About a decade ago, Lisa started helping Wayne run the farm full-time. She hopes their efforts will allow her to pass on a durable farm to her daughter, Alexandra.

Twenty-five miles further Down East, the Beal family is sorting the certified organic wild blueberries they’ve raked since 1991 on Moon Hill Farm in Whiting. Only about 12% of Maine’s “wild” blueberries are organic, but “there’s a lot of potential” to grow this hot market through fresh sales, says University of Maine blueberry expert David Yarborough.

Tim Beal also has deep roots in Washington County where his family goes back four generations. Tim started raking blueberries when he was eight; his father, a Bangor Daily News bureau chief,