6 minute read

T S Eliot and Magdalene: R D Williams

T S ELIOT AND MAGDALENE

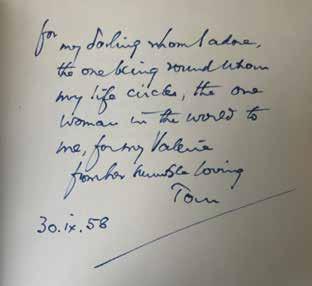

As readers of this Magazine will be aware, we have recently received a generous bequest from the estate of T S Eliot’s widow, Valerie, including a comprehensive range of first editions of his work (many of them inscribed in moving terms to Valerie), translations into a wide range of languages, including Tamil and Romanian, and Eliot’s Nobel gold medal, which can now join his Nobel laureate’s diploma already held by the College. We are also in possession of what is certainly one of the best-known portraits of Eliot, Wyndham Lewis’s 1949 painting; his earlier, 1938, portrait is widely considered the more striking and original, but Eliot is on record as saying that he would be happy at the thought that the Magdalene portrait would be how he was to be remembered.

Advertisement

T S Eliot by Wyndham Lewis (1949)

Dedication in Om poesi (Stockholm 1958), the Swedish translation of On poetry and poets

The College which recognised Eliot’s stature by electing him as an Honorary Fellow thus retains a significant link with him – celebrated not long ago with one of those superb exhibitions from our Archives regularly mounted by Dr Hyam and the library staff here. If IA Richards had had his way and succeeded in persuading Eliot to take up an academic position at Cambridge, we might indeed have had a closer connection still; but it is no small thing to have this link with one of the greatest English language poets of the past century. Richards was a consistent and eloquent advocate for Eliot, and Eliot, when challenged as to the meaning of some of his lines, was alleged to refer readers to Richards for illumination. Not actually very likely, though it makes a good story: we know that Eliot was not at all happy with Richards’s critical theories in general and their application to his own work in particular, and Richards’s claim that The Waste Land represented a complete dissociation between poetry and belief was one that Eliot sharply repudiated. But the friendship between the two men was important to both, and important also to the development of critical discourse in the UK and its academic naturalisation in Cambridge and elsewhere. Peter Ackroyd, in his idiosyncratic biography of Eliot in 1984, argued that Eliot’s public stature as a new kind of literary critic, someone who did not see commenting on poetry as an occasion for impressionistic or uplifting waffle, gave substantial encouragement to writers like Richards who were shaping a serious theoretical framework for such discussion and substantial reinforcement to the idea that

this might be a subject worth studying in a university. Whatever the details of the process, it is hard to deny that literary criticism as it has been understood for most of last three-quarters of a century would be radically different if it were not for Eliot’s essays and the often involved and conflicted relations between Eliot and some of the major names in the development of that critical tradition.

Eliot’s criticism is one of the more contested bits of the legacy, of course. There are early lectures and essays that do not bear re-reading. Eliot himself effectively suppressed some of that early work, embarrassed both by its Olympian certainties and by its cultural and moral insensitivities (such as the justly notorious reference to the bad influence of ‘free-thinking Jews’ in his 1933 After Strange Gods). But it was in some ways just that Olympian authority that provoked passion, interest and sometimes articulate and sophisticated revolt in so many readers. Our other great mid-twentieth-century literary hero at Magdalene, CS Lewis, battled vigorously against many of Eliot’s judgements, and his magnificent Preface to Paradise Lost exists partly because of Lewis’s intense disagreement with a range of Eliotic obiter dicta, not only Eliot’s view of Milton but his view of criticism itself. Lewis is understandably sceptical about Eliot’s claim that the best critic of poetry is the good poet; this is all very well – says CSL – when you have a poet generally agreed to be good, but it is not much use in helping you to know where to look for help in critical reading when it is not clear where the great poets are. Circularity threatens: you need a good critic to help you work out whether a poet is good; and the disciplines of criticism are importantly not the same as the disciplines of poetry itself.

Lewis’s challenge, though, assumes that there are indeed critical disciplines; and while he could be dismissive of the exercise of critical scholarship on contemporary writing (needing critical help with modern literature was like needing your nanny to blow your nose for you, in one of his more mordant phrases), he knew – no less than Richards – that critical reading was a serious professional task for the academic. Eliot, by bringing major critical discussions into the cultural mainstream in such a distinctive and provocative way, provided his own witness to this, and its effectiveness is not in doubt.

Eliot is at long last receiving the kind of biographical treatment he deserves. Robert Crawford published last year the first volume of what will be a definitive account of his life and writings; it is a biography that, on the showing of this first volume, brings out with special clarity aspects of Eliot’s intellectual journey that have not been fully recognised – for example, the fact that he was already reading widely and deeply in the history of mystical literature, Eastern and Western, even in his undergraduate years at Harvard. A proper appreciation of Eliot’s stature is bound to include a recognition of this rich and diverse intellectual formation. As much as Yeats (whom we also celebrated here last year with a wonderfully lively conference), he was a major poet because he refused to be ‘just’ a poet: the

poetic work grew from and fed back into a set of passionate commitments about society, language and the essence of what it is to be human. As I write, we are mourning the death of Geoffrey Hill – one of those who have brilliantly kept alive the tradition of demanding critical argument and social polemic alongside their poetry. After a few months of unusual mendacity, rancour, hysteria and vulgarity in public and political debate in this country, we should be able to recognise just how and why figures like Eliot, Yeats and Hill matter so profoundly to our cultural health. The careful scrutiny of words and the complex and soulenlarging excess of words – that is, good criticism and good poetry – are more necessary than ever if we are to step back from the dominance of self-interested rhetoric that has no literacy about the past and no vision for the future. Eliot as critic as well as Eliot as poet contributed as much as any public figure of the twentieth century to the struggle for clarity and depth alike in language. Infuriating and inspiring in almost equal measure, he shows us what the poet as public intellectual can be. It is right that we should be proud of our association with him here in Magdalene; and wonderful that we shall have so significant a visible reminder of our connection in the shape of Valerie Eliot’s bequest.

R D W

Another volume from the bequest