15 minute read

Sabbaticals

from Agora Fall 2020

Researcher Subject of Police Investigation

by DAVID FALDET, Professor of English

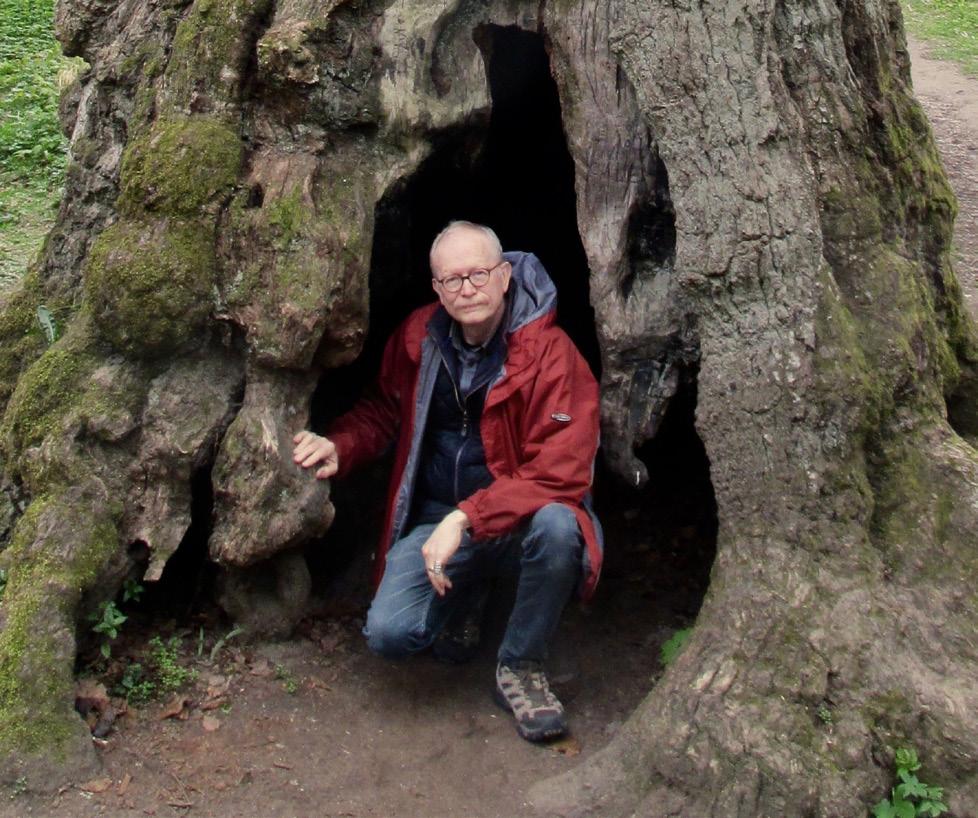

Sure enough, the title of this sab- into new rock, somebatical reflection applies to me: times uplifted again the suspect in a possible crime to mountain heights, committed on a remote Scottish farm in only to be worn slowly the name of historical research. When down into plains or river contacted over the phone by a constable outwash. My project was in the East Midlands, the first excuse to research how popular I blurted was: “I’m an academic!” Was that, I later wondered, my way of saying I don’t know any better, am not in the criminal line of work, or, perhaps, am above the laws that govern ordinary criminal offenses? In any case, my sabbatical project was not to commit rural crimes, but rather to research the reactions of over a dozen well-known British writers to earth science as established by the Scotsman, James Hutton. In this report, I’ll discuss adventures in pursuit of Hutton writers reacted to this vision of an ancient, unfixed earth, especially in the way they wrote about soil. It took over a century for fiction to invent a way of depicting Hutton’s facts. In the meantime, writers had their eyes to the ground, and my project was to reflect on what, exactly, they saw. which he penned his observations on David Faldet in the bowels of the Birnam oak—an ancient tree not far from where Beatrix Potter first drafted Peter Rabbit IMAGES COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR and a handful of those authors: Charles My brush with police authority came soil loss, marl, and the effects of yearly Darwin, Mary Shelley, Beatrix Potter, in researching Hutton himself. Hut- temperature on crop growth. Rachel and H.G. Wells, adventures that took ton developed his theories of erosion and I snapping photographs from the place in spring 2019 while my wife while farming in Berwickshire, just perimeter fences of the property made Rachel and I were in England to direct north of Scotland’s border with Eng- the neighborhood suspicious. Someone Luther’s Nottingham Program. Though land. I wanted to get a few pictures took down my vehicle’s number plate. my Paideia grant was meant to let me of the fields whose plowing Hutton When Rachel and I arrived back to our return for follow-up and to explore the revolutionized, and of the farmhouse in house in Nottingham I found a note, lives of other writers, sadly the Covid slipped through our mail slot, that told pandemic meant these spring 2019 trav- me to contact a detective, “in reference els in Great Britain were the extent of to your case.” My case? my on-site learning: up-front reconnaissance before a sabbatical year of reading and writing. Fortunately the officer decided that, as an academic, I truly was harmless, had not committed a crime, and wasn’t likely Hutton (1726-1797) was the first to to return to Scotland to commit a crime. assert the reality of deep time: an earth history of not the 6000 years calculated by Bishop Ussher (1581-1656) using The “harmless” part may or may not have been true. the Bible and other ancient writings, For example, I also insisted that Rachel but rather time, Hutton said, with “no accompany me to Siccar Point, a remote vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an coastal promontory east of Edinburgh end.”1 Hutton asserted an earth in flux, on the North Sea where Hutton saw the still hot at its center and relentlessly deep age of earth revealed in gray rock, eroded at its surface: continents in up- a hardened slurry of ancient eroded lift, underlain by churning magma, and sediment, upended by subterranean hills and fields constantly worn away, pressure from horizontal to vertical, and only to have their rubble and detritus then overlaid with horizontal layers of transformed under heat and pressure Slighhouses, James Hutton’s farm red sandstone that had been formed in

an entirely separate era of erosion. To view Siccar Point we needed to take a public footpath through a series of pastures. Next to the entrance stile at the car park, a sign warned: “Bull.” I, the academic, was not about to let a farm animal come between me and a foundational moment of scientific history. Rachel had different feelings.

Siccar Point bull and cow After suggesting several milder solutions, I maybe suggested divorce, but backed down to proposing a less direct route, which would put us outside the stone pasture wall but along the top of a sea cliff. Rachel steeled herself and tried not to look down. I got to see Siccar Point. No one died. The bull, however, was very real, large, unfriendly, and had planted himself in the wall opening through which Rachel and I would have passed had we taken the pasture footpath. I was glad to gaze at this grim bovine giant and his herd from a distance and on the safe opposite side of a wall rather than eye to eye, with nothing but air and a short expanse of pasture grass between us. It was, after all, his turf. Some men have guardian angels. I have a guardian spouse. Treading the footpaths of intellectual giants other than Hutton proved less dangerous. Nothing, in fact, could be more comforting than, in the English county of Kent, strolling the Sand Walk: a circular path Charles Darwin walked daily, keeping track of his distance with stones deposited at the end of each round. Lost in his thoughts, Darwin sometimes changed the length of his daily regime because his children, for their amusement, either subtracted from or added rocks to his pile. I pocketed an almond-sized flint, partly coated in the local chalk, from the gravel path to sit on my desk at home, a reminder of the ground trod by a visionary, though absent-minded, hero.

Darwin’s revolutionary theory of natural selection was made possible by Hutton’s new vista on time and geological change as accepted and popularized by English geologist Charles Lyell. Darwin, as geologist, turned his attention to the creation and erosion of coral reefs, volcanic islands, and the South American continent, the place where he experienced his first earthquake and witnessed the cataclysmic shifts it made around him in the neighborhood of Concepción, Chile. My key interest in visiting Darwin’s Down House was to see the “worm stone” at the back of his property, created by Darwin and his son to measure the annuDarwin’s sand walk al rate at which soil rose up around the stone. The work of Darwin’s on which I focused was his lifetime bestseller: The Formation of Vegetable Mould, Through the Action of Worms, with Observations on their Habits (1881). As I stood at the worm stone and looked south across the nearest expanse of closely trimmed grass I could see hundreds of little piles of earth: the sort of worm castings that inspired Darwin’s book. Darwin has been popularly associated with chimpanzees, whose shared ancestry with humans he posited in The Descent of Man, or with Galapagos finches, whose wide range of closely related species correlated with the distinct and varied Galapagos island environmental histories: proof of the theory advanced in On the Origin of Species. Darwin, however, spent very little time observing these species. In contrast, off and on for over thirty years he closely studied earthworms. In his “earthworm book,” Darwin studied the rate at which earthworms cycled soil: bringing it up from below and depositing it at the mouth of their burrow on the ground surface. In the sites in and around Kent where Darwin carried out his studies he discovered that worms bury solid objects at a rate averaging 2 inches per decade. He brought a shovel with him to Stone-

Darwin’s worm stone

henge to gather evidence at that famous ancient place. He enlisted the aid of his friend Thomas Henry Farrar of Abinger Hall to study the burial process of a Roman villa discovered on Farrar’s estate. Using Roman coins found during the dig to date the structure, Darwin calculated the rate at which the site had sunk beneath the soil. Once the site was unearthed and cleaned, Farrar tabulated the rate at which earthworms continued to cast up earth on its mosaic floors: a process that would eventually re-bury the villa. “It appears at first sight a surprising fact,” Darwin mused, “that this field . . . should have been cultivated and ploughed during many years, and that not a vestige of these buildings should have been discovered. No with the statue of Humphry Davy, a native son of that city. The statue commemorates Davy’s invention of a safety lamp that lessened the likelihood of workplace explosions for Cornish miners. Davy, though diminutive in stature, was a titanic pioneer of electrochemistry. He mapped the interface of chemistry and electrical currents in soil activity. These researches were studied and discussed by the teenaged Mary Shelley (1797-1851) and her poet husband Percy. Mary read Davy’s novel a spark, intimately connected to the process of decay, enlivens the “clay”

one even suspected that the remains of a Roman villa lay hidden close beneath the surface.”2 The slow, patient work of tiny annelids totally erased even the monumental remains of what had once been a mighty Elements of Chemical Philosophy (1812) as she drafted Frankenstein. In Mary’s

empire. of Victor Frankenstein’s creature. It was also a pleasure to trace the footsteps of children’s author Beatrix Potter (1866-1943). Potter had a deep love of the soil, which led her to move to the Lake District and take up farming after spending her first forty years, spent mainly in London, suffocating under the upwardly aspiring middle-class propriety of her parents. Annual family trips to Scotland, and later to the Lake District, where her father could hunt, fish, and pursue amateur photography, gave a young Beatrix a taste of the rural life that made her heart sing and which she was later able to achieve for herself, much to her mother’s horror. Exploring Potter sites in Perthshire, Scotland, Rachel and I walked through Birnam Wood (made famous in Shake-

A pleasant encounter during my research took place much further west in Penzance, Cornwall, where Rachel and I came face to face on Market Jew Street Rachel Faldet beneath a Birnum Wood sycamore Humphry Davy statue, Penzance

speare’s Macbeth) to the River Tay to see Eastwood House, situated in a scenic patch of lawn on the facing shore. At Eastwood House in 1893 Potter drafted her first version of the Peter Rabbit story, which she sent to the ailing son of her former governess. Dalguise, the nearby village Potter’s family visited for many of her childhood summers, is in the heart of an area of Perthshire known for its big trees. Walking the braes of Perthshire’s burns, or its rigs and howes (the banks of its streams, or its ridges and hollows) between the massive trunks of oak and Douglas Fir, it is easy to sense enchantment, such as that invoked by Macbeth’s witches, or that which brought to life in Potter’s imagination a small universe of talking animals who, with mixed success, accommodated their animal obsessions to a British standard of polite behavior (in other words, animals who lived the same sort of life Potter did). Rachel and I had to watch our step for cow manure when we picked our way from Beatrix Potter’s Hill Top farm to a small but scenic impoundment of water: Moss

Beatrix Potter’s Hill Top home

Eccles Tarn. Our route began as a paved work in English and German, became village street in Near Sawrey morphed the first person to successfully germiinto a dirt farm lane and petered out nate several species of fungi, recognized into a narrow footpath. At Moss Eccles before anyone else that the reproductive Tarn Potter drew inspiration for her bodies of fungi are but small extensions fishing story: The Tale of Mr. Jeremy of a much larger mycelial mass that conFisher, perhaps my favorite of her chil- stitutes the core body, and, in defiance of dren’s books. The steep walk up to the the leading authority of the day, became Tarn, situated between Bank Wood and convinced that fungi develop symbipastured meadows, was damp, and the otic (as versus parasitic) relationships stone walls on either side of our route, in lichens as well as other interspecies Stones Lane, moss-covered. It was easy pairings. As a woman, however, Potter’s to imagine Potter finding there what work was rebuffed. She turned, instead, most absorbed her in the decade lead- to children’s books. In my study I looked ing up to her start as a beloved author: at the way dirt became more central and fungi. more celebrated in her stories. If Potter had met with success in her main preoccupation of the 1890s, she would have become a mycologist. What began as a few watercolor sketches of mushrooms in the late 1880s, culminated in obsessive study of fungi and presentation of her paper, “On the germination of the spores of Agaricineae,“ at London’s Linnaean Society in 1897. With hit-and-miss collaboration and little instruction Potter read all the most important fungi Stones Road to Moss Eccles Tarn The first British writer to fully realize Hutton’s deep time vision in a work of fiction was H. G. Wells (1866-1946). In Wells’s breakthrough novel, The Time Machine, an inventor in the posh west London suburb of Richmond invents an apparatus that will allow him to travel through time: a sort of bicycle on the seat of which he can travel into the future or into the past as easily as one might pedal east to the corner shop for a parcel of paper or west to a local pub for a pint of ale. When Wells’s Time Traveller activates his machine, hurtling forward in time, even though he remains stationary in place, he sees: “The whole surface of the earth . . . changed – melting and flowing under my eyes.”3 Near the end of the novel the Time Traveller goes forward thirty million years, and from that perspective sees his Thames-side house lot converted to an ocean beach, and both the planet and sun cooling with age. The contrivance of Wells’s imaginary machine made the normally slow speed of geological change visible. The dangers I faced in tracing the footsteps of H.G. Wells, the science educator turned writer who first depicted Hutton’s geology in fiction, came not from farm animals or muddy tracks but traffic and traffic wardens. I recorded the locations of key scenes in the action of The Time Machine and War of the Worlds. Tracking down these spots, I found out what Wells meant when he wrote to a friend as he penned War of the Worlds: “I completely wreck and destroy Woking – killing my neighbors in painful and eccentric ways – then proceed via Kingston and Richmond to London, which I sack, selecting South Kensington for feats of peculiar atrocity.”4 Woking, in the Surrey suburbs of the capital, was where Wells lived and wrote his novel. South Kensington was where he studied

science and later worked as a science up research impossible. The end of my NOTES teacher and science education journalist. sabbatical year finds me with a draft 1. James Hutton, “Theory of the Earth,” Kingston and Richmond, in between, of a book manuscript in hand: Another Transactions of the Royal Society of were affluent suburbs, considered at the One Writes the Dust: The New Earth Edinburgh, v. 1 (1788): 209 – 303, 303. time a safe and leafy escape from urban Consciousness of Two Darwins, Dickens, 2. Charles Darwin, The Formation of Vegetable congestion. Victorian Poets, and the authors of Fran- Mould through the Action of Worms, with Wells set his scientific romances in the comforts of suburbia, but through novel twists of science-fueled fantasy turned these places upside down. To stand kenstein, Alice in Wonderland, Dracula, Peter Rabbit, and War of the Worlds. My thanks to the Paideia program, not only for funding to carry out my Observations on their Habits (London: John Murray, 1881): 183. 3. H.G. Wells The Time Machine, from H.G. Wells: Six Novels (San Diego: Canterbury Classics, 2012): 1 – 57, 12. at the spots where Martians incinerated Londoners with their heat ray I research and writing, but also for inspiration. My interest and knowledge 4. H.G. Wells, The Correspondence of H.G. Wells. Ed. David C. Smith. 4 vols. double parked or defied residents-only of Frankenstein and the writings of (London: Pickering and Chatto, 1998): parking restrictions, and then watched Charles Darwin have been fed by years v. 1, 261. carefully that I didn’t open my car door of teaching these works in Paideia 111: into oncoming traffic. The Tudor revival Enduring Questions. Also, I would not suburban villas that would have still have started reading H. G. Wells had looked raw and new in Wells’s days, I not, in 1990, been asked by colleague now have lichens and rising damp on Linda Shearing to join her and Dentheir foundations and front garden nis Barnaal in teaching what was then spaces bricked over to accommodate called a Paideia Two course: Speculative parking space for Audis and BMWs. As Fiction. Thanks Paideia, for making my for the place of rock and soil in Wells’s education an ongoing one, and one that book about a Martian invasion, he de- in true Luther College fashion is both picted his Martians as having intellects interdisciplinary and multicultural. that made humans look like ants, and a human metropolis like London no more than an anthill, disturbed by Martian heat rays. The reason for Martian invasion involved geological history. In the novel, Mars, further out from the sun, is older than earth, and beginning to cool and die. The Martians, who happen to be interested in feasting on human blood, will also buy six million years of time by emigrating from their original planet to our newer (and still more molten) one. The explorations that West London site of Martian landing in H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds preceded my sabbatical year of research and writing neither put me behind bars nor left me trampled by a disgruntled bull, nor run down by congested suburban traffic. Instead, I was inspired. My only disappointment was that the Covid pandemic made my return for follow-