9 minute read

A Living History Revised and Revived

from The Lead: Fall 2023

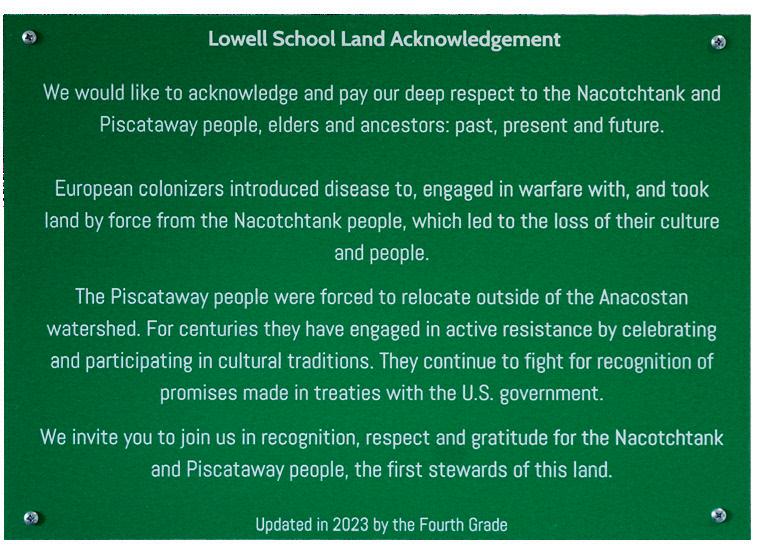

Lowell’s Class of 2027 combined advocacy, research, and design to pay respect to the first stewards of our campus

In 4th grade, Lowell’s integrated curriculum ties together lessons in reading, writing, and social studies to explore the history of and current issues facing Indigenous people. This lens of the Indigenous experience shapes countless units throughout the year, showing up in book reports, art creations, and social justice projects. In the 2022–2023 school year, one project stood out as an actionable way for our students to create change in our own community.

On a crisp November day in 2022, the entire Primary School assembled on the Front Field for a bi-weekly community gathering. In recognition of Native American Heritage Month, Lowell’s 4th graders presented some of their social studies learning to fellow students from Kindergarten through 5th grade. As in years past, they talked about their exploration of the history of Lowell School and the land its campus sits on. “A land acknowledgment is when you recognize and name the people who were the original and first to live in an area, even if there are other people living on the land now,” one student explained before reading aloud from the then-current Lowell School Land Acknowledgment.

But these 4th graders noticed something else significant in their research: changes had to be made! And so, with an audience of their fellow students, 4th graders stated their commitment to a months-long project to improve and update Lowell’s land acknowledgment and make it more visible. “It was important to me to update the land acknowledgment because it was outdated and incorrect, and I feel like Indigenous people could be better represented,” said student Jackie, thinking back on their work.

With student interest leading the charge, teachers Emily and Elizabeth helped guide their classes through the process of creating a thoughtful statement representative of the whole school. “Indigenous communities ask that when an institution writes a land acknowledgment, certain steps be taken to make it meaningful,” they shared. “Students edited Lowell’s to be more up-to-date with the guidelines Indigenous groups provide for such efforts.” (See below for guidelines from the Native Governance Center.)

As a class, 4th graders read and reviewed these guidelines. Emily and Elizabeth challenged them to do their own research into each of the Indigenous groups named in the original version of the acknowledgment—Piscataway, Pamunkey, Nanichoke, Mattaponi, Chickahomini, Monacan, and Pow’hatan—to determine if they had once inhabited the area now bordered by Rock Creek Park to the west and Kalmia Road to the north. Notably, the Nacotchtank people, who inhabited a major trading center in the Washington area, were added in revisions.

Students also took to heart the guidance, “Don’t sugarcoat the past,” and “Land acknowledgments shouldn’t be grim.” It was a delicate task to balance, to be sure. Ultimately, the 4th graders determined it was important to recognize the loss of life, land, and culture as a result of European interference with the Nacotchtank and Piscataway people and to celebrate their ongoing efforts toward resistance and reparation.

“The biggest lesson I learned from this project was that Indigenous people are incredibly diverse,” reflected 4th grader Jackie. “There are so many more groups than I would have ever known about had I not worked on the land acknowledgment.”

Research about the land our campus occupies is not only an important vehicle for teaching about reliable sources, fact-finding, and the history of our country’s relations with Indigenous groups, but it also aligns with Learning for Justice’s Social Justice Standards. As they learn to value diversity, students at this age seek to understand that, “the way groups of people are treated today, and the way they have been treated in the past, shapes their group identity and culture,” (DI.6–8.10 from Social Justice Standards: The Learning for Justice Anti-Bias Framework Second Edition, 2022).

In December, Emily and Elizabeth invited several administrators to share in the progress made so far: “Our amazing students are adamant that they present their revised land acknowledgment and process behind the revision in front of decision makers at Lowell.” Fourth graders were determined to enact change and sought assistance from their teachers to reach the people “in charge,” creating the list of invitees themselves.

As the face of the Main Building’s front desk, the students unanimously identified Operations Coordinator Marsi as a key stakeholder. “The presentation was well thought out, and the students really did their research. I learned a lot that day,” said Marsi, reflecting on their presentation. “Students clearly cared about this project. It mattered to them, not because the teachers made it so, but because they saw the importance in the history of the land and the value in taking these steps themselves.”

Head of School Donna also received a coveted invite. “I was impressed with 4th graders for asking thoughtful questions and presenting their work in such a professional manner. I immediately offered my support for their new land acknowledgment,” she said, adding that the requests she sometimes fields from students are focused on a want or solving problems for themselves. This one stood out as an educational benefit to the whole community by centering the experiences of others.

Buoyed by the support of Lowell’s leaders, students finessed and finalized the revised language when they returned from Winter Break. But their work was only halfway done. Another important goal of the project was making the acknowledgment visible to Lowell students and any visitors to the school. Following numerous brainstorming sessions where they identified permissions and manufacturing challenges, students asked for assistance from the professionals in their community to implement their vision

To begin, 4th graders wanted to ensure that Lowell students and staff would regularly be reminded of the land’s history. What about every time someone enters a campus building? A small task force teamed up with Primary School Academic Technologist Daniel to create signs that are now displayed at the entrance to each division.

Using design thinking to guide their solution, students considered the needs of the greater Lowell community. They did field research to look for other signage around campus, noticing what it communicates, why it’s important, and details of its design, and created prototypes from paper and cardboard. The team voted on the merits of each prototype— fonts, spacing, and readability—before landing on a final iteration. Along the way, they learned elements of practical design, answering questions like “What will make this stand out visually?” “Is it easy to read for everyone?” and “What materials should be used to ensure the sign lasts?”

“Utilizing the STEAM Workshop to design and make signs for the land acknowledgment project was another organic way to take the students through the design thinking process,” said Daniel. “One of the driving goals I have for technology use in the Primary division is to look for ways that it can be embedded into the classroom curriculum. Making signs with the laser cutter is fun, but linking its use to this project-based unit that makes a positive change not only teaches a transferable skill but also helps the classroom content ‘stick.’”

In January, another small group met with members of Lowell’s communications staff to discuss where the land acknowledgment could be displayed on the website. They were asked to think again about the goal and audience of the acknowledgment, and make hypotheses about how different audiences—be they prospective families, faculty and staff, or casual browsers—might interact with the website. Another team, prepared with a Google Slides presentation, floated ideas for an article or social media post to be shared with the broader community. Students practiced using persuasive language to relate why it was important to highlight the changes to the land acknowledgment. Those ideas led to the very piece you’re reading now!

In addition to signage and written formats, students sought out active opportunities to share their learning. When hundreds of visitors gathered in the gym to kick off Grandguest Day in March, 4th graders were there to open the assembly with a presentation of the new land acknowledgment. In another instance, students learned that several areas close to Lowell’s campus share a similar provenance and relationship with Indigenous inhabitants. They recognized that the work they completed could be of use to others in the neighborhood. During a field trip to nearby Koiner Farm in Silver Spring, students recited the revised land acknowledgment and offered it to staff as a template to inspire their own research and respect for the land they farm. The founder and executive director of the farm’s conservancy was honored to receive this gift—a gift that Lowell’s Class of 2027 has ensured will enrich and educate our community for years to come.

Lowell School Land Acknowledgment (revised 2023)

Key Components for Creating an Indigenous Land Acknowledgment Statement

(from the Native Governance Center, 2019)

Start with self-reflection:

• Why am I doing this land acknowledgment? (If you’re hoping to inspire others to take action to support Indigenous communities, you’re on the right track.)

• What is my end goal?

• When will I have the largest impact?

Do your homework. Put in the time necessary to research the following topics:

• The Indigenous people to whom the land belongs.

• The history of the land and any related treaties.

• Names of living Indigenous people from these communities. If you’re presenting on behalf of your work in a certain field, highlight Indigenous people who currently work in that field. Indigenous place names and language.

• Correct pronunciation for the names of the Tribes, places, and individuals that you’re including.

Use appropriate language. Don’t sugarcoat the past. Use terms like genocide, ethnic cleansing, stolen land, and forced removal to reflect actions taken by colonizers.

Use past, present, and future tenses. Indigenous people are still here, and they’re thriving. Don’t treat them as a relic of the past.

Land acknowledgments shouldn’t be grim. They should function as living celebrations of Indigenous communities. Ask yourself, “How am I leaving Indigenous people in a stronger, more empowered place because of this land acknowledgment?” Focus on the positivity of who Indigenous people are today.