63 minute read

Reviews

Albums Reviews

The Strokes — The New Abnormal (columbia) In 2005, in the lead up to the release of First Impressions of Earth, and perhaps fearing the worst, Albert Hammond Jr told NME how The Strokes had banked enough credibility to “last us a lifetime”. It didn’t seem like a bold claim at the time, but not even Hammond could have expected it to be as true as it remains today.

Advertisement

It’s now 2020 and The Strokes endure on a wave of goodwill, nostalgia and a sense of what we owe them. First Impressions of Earth came out and gave us a beefier, bloated Strokes who shredded enough on ‘Heart in a Cage’ and ‘Juicebox’ for us to go with it, outrageously flirting with Barry Manilow on ‘Razorblade’ before the album fell off a cliff. The following Angles (2011) and Comedown Machine (2013) sold 3 copies between them but still we loved The Strokes. When a band member releases a solo project, we wish it was a new Strokes album instead. When The Voidz tour, we buy tickets in the hope that Julian will perform the demo version of ‘You Only Live Once’. Even when he doesn’t you still get to see Julian Casablancas from The Strokes. That’s how much credibility the first two Strokes albums banked – it’s both impressive and depressing.

The obvious question is why hasn’t another band meant as much to people in the last 20 years. But what’s more apparent as a new album comes over the horizon once again, is how we’ve frozen the band in one time and they’ve frozen themselves in another. Despite the sound of Angles and Comedown Machine (and 2016’s 3-track Future Present Past EP), most of us still have The Strokes down as the band that only strum downwards; ’70s New York revivalists; Converse and jeans and perhaps even a tie, from a time when boys were boys and bands were bands. But they’ve been leaning into ’80s new wave – from The Police to Blondie to A-ha – for much longer than they ever spent aping Modern Lovers; Casablancas their Marty McFly longer than their Joey Ramone. And that’s where they still are with The New Abnormal – an album that features a Basquiat painting as its cover: a stamp of cultural significance and modern retro cool if there ever was one in 2020.

What Albert Hammond Jr meant in that NME interview was that The Strokes were going to do whatever the fuck they like from now on, which, in part, translated to them playing slower and longer. The New Abnormal certainly adheres to that, with a few exceptions, including opening red herring ‘The Adults Are Talking’ – a close relative to Comedown Machine’s ode to ‘Take On Me’: ‘One Way Trigger’. This is what “the Strokes sound” is now – a wafer-thin drum machine fizzing at a skittish pace, with Casablancas properly singing over it and an endless guitar line that sounds like it’s coming from a keyboard. It’s as strong as the best parts of Comedown Machine (and there were some best parts), but then it’s gone again, slowly fading not quite to nothing but some on-mic studio chatter where Casablanca appears to say, “So let’s go back to the old key, old tempo, everything.” That old tempo, it turns out, is half the speed. The following ‘Selfless’ is largely forgettable, even if it does feature Casablancas reaching new heights in his falsetto singing. He sings way up there on ‘Eternal Summer’ too – a strange, plodding number of U2 stadium rock drums and a chorus that has Casablancas fully shouting, “I can’t believe it / Life is such a funny journey / Psychedelic / This is the eleventh hour,” like a drunk yelling at the wind. It’s the flabbiest the band have ever been, who, by the way, have also retired their full-stop endings and now opt for a mix of slow fades and clips of unidentified new Strokes tunes, as if they’ve been recording over old demo tapes.

‘Eternal Summer’ is not Casablancas’ finest hour as a lyricist, but as a writer who’s always built with abstraction in order to deliver a moment of clarity that can feel profound, the drum-less ‘At The Door’ delivers when he growls, “Have to fight what I can’t see / Not trying to build a legacy.” It’s a highlight, even if it takes forever to end, as does every song here.

Better still is ‘Bad Decisions’, because it sounds like a Cure song from a John Hughes film, thanks almost entirely to Nick Valensi’s string-hopping guitar riff. And while ‘Not The Same Anymore’ falls fowl to a chugging chorus, its verses almost have something of Nina Simone about them… briefly.

If it sounds like I’m clutching at straws here perhaps it’s because I’m trying to swerve ‘Why Are Sundays So Depressing’ on account of its title alone – coming to an Alan Partridge phone-in near you. Unfortunately, the song itself is somehow completely horrible and a total non-event, plagued by a distracting electronic whipping sound and the laziest of back and forths between Valensi and Hammond Jr.

The most confusing moment on The New Abnormal though is ‘Brooklyn Bridge to Chorus’ – a ludicrous disco track that is initially appalling until you realise it’s the best thing The Strokes have done in a long time. The name’s not a good start, and what they do with it is worse, reaching for a level of meta that Robbie Williams hit when he sang, “And that’s a good line to take it to the bridge,” on ‘Strong’. The Strokes do pretty much the same thing, with Casablancas saying “break” in one brief silence, and, “Can we switch to the chorus right now,” just before they do. It’s probably not want you want from The Strokes, but in case you didn’t get it before Casablancas starts crowing, “I want new friends but they don’t want me,” they’re clearly having a laugh here, and it feels like a relief. Finally, The Strokes stopped being too cool do what they really want, which is this case was to build a song as ridiculous and as fun as this around a two-finger synth hook and the odd Pet Shop Boys blast. The New Abnormal is still a way from being The Strokes’ Tranquility Base Hotel and Casino, but at moments its getting there. It’s certainly self-indulgent enough, and admirably pig-headed too. For an album that’s only 9 tracks long, it

goes on forever, and I’ve not even passed comment on the closing ‘Ode to The Mets’. But we’ll be back here. The New Abnormal will become your fifth favourite Strokes album (there really is little going on on Angles). We’ll forget that the band haven’t sounded like ‘The Modern Age’ since ‘The Modern Age’. We’ll find something to love in what they do next. For a lifetime. 5/10 Stuart Stubbs

Half Waif — The Caretaker (anti-) Running has long been a useful symbol for songwriters who want to provoke a direct physical response as they describe abstract emotions. We can run in circles, run away with our lover, run up that hill to make a deal with god. Or, we can just run, towards nothing in particular. That’s the kind of running Half Waif – aka Nandi Rose – writes about on The Caretaker. “Going nowhere fast,” she belts out in its opening moments, sounding as if she’s in pain, digging deep for resilience as the synths around her threaten to swallow her up. Rose is an impeccable writer, and on her follow-up to 2017’s Lavender she pulls power and introspection out of quotidian moments, like going for that run you really don’t feel you can face.

Let’s get this out of the way early: The Caretaker is fantastic. It’s a ballsy pop record that often uses restraint and delayed payoff to create a deeper connection. Rose is good at writing choruses, but her songs keep their distance more often than not, like she’s meeting us on her own terms. The album employs the same distancing technique – keeping those close to us at arm’s length to better ourselves, and letting friends in when the timing is right. “Don’t you worry about me, I won’t worry about you,” she sings on single ‘Ordinary Talk’ – “I’ve got places in my mind that I’ll never find if you’re holding my hand like you always do.” The song blossoms with layered vocals, slinking keys and drums that you could sink into. It’s a gorgeous slow burn at the core of the album’s balance between opening up and closing off as a person.

Her melodies and production are both taut and winding, dodging easy categorisation. Drum machines and sour keyboards meet piano, flute, and clarinet as these individual songs grow. It’s a clever reflection of the way her lyrics grow in potency. Her words initially read as cold across the album, until their subtleties shine through, revealing deep empathy and introspection. On ‘My Best Self ’, she reframes our generation’s obsession with identity from self-obsession to a selfaware embrace of interconnectivity. By the end of The Caretaker you might better understand where you fit in to the world, and how the world should fit to suit you. 8/10 Stephen Butchard

C.A.R. — Crossing Prior Street (ransom note) At 16 years old, Chloé Raunet fled her native Vancouver for London, trying to escape her difficult childhood. With her third album under the moniker C.A.R., Raunet uses 42 minutes of sophisticated, electronic pop to tell her story and make amends with her past and – perhaps – her present. Crossing Prior Street, whose title is an homage to the London street that was the first place the Franco-Canadian producer has ever called home, is a ten-track journey through a healing process; an experiment in leftfield pop that explores the scarcity and loneliness of life in a metropolis. Linked by a drum machine that sets her narrative’s heartbeat (the main recurring element here), Raunet’s vocals tell her story among metallic filtered voices and pop singing, helped by new wave/post-punk inspired synths. The dark, gothic atmosphere of tracks like ‘Pressure Drop’ is counterbalanced by tribal pieces like ‘Steals the Dance’. It’s the sound of the street, with sirens, drills, steps, and disturbed transmissions, that permeates through the tracks. This is a record on which the rhythm of a big city enters the personal story of a teenager looking for herself, and becomes a part of her. 6/10 Guia Cortessa

Hamilton Leithauser — The Loves of Your Life (glassnote) You can’t help but feel that people like Hamilton Leithauser attract good stories. I’m not talking about the wrung-out nostalgia highs and back-chat from the good days, before his old band The Walkmen announced a playfully “extreme” hiatus (that’s lasted eight years to date). His third solo record, The Loves of Your Life, is packed with tales about real people, from rock’n’roll singers who can’t hit the notes to strangers who hide from their flatmates in old cinemas, and friends whose parents still pay their rent. It’s a further breakaway from the great, dirty city sounds he helped revive in the early ’00s, but it lounges around the same subjects with a renewed and lighthearted sense of reverie.

The Leonard Cohen-style triplet guitar has been trashed and replaced by the bare bones of Freakbeat, the occasional doo-wop backing harmonies (‘Isabella’) and island-bounce blues (‘Wack Jack’) of Dylan’s Infidels. There’s less of the melodic ’50s crooner he perfected with Rostam Batmanglij on 2016’s I Had A Dream, but it returns to the same sweet spots. The fantastical creation narrative plays out like

surrealist folklore; magical accounts of humanity are tenderly cast with an even more guttural, well-travelled sing-shout. A couple of quieter moments are so emotively strung that Leithauser cuts a beat, as if so engrossed in watching his own stories unfold that he forgets it’s his job to fill in the lines.

The one moment of Leithauser’s own self-reflection seeps into the final track – a piano ballad backed by his own kids – where his own gorgeously weathered vocal mediates on forgiveness. But even the most earnest of subjects are humorous, poetic and engaging – he’s writing with one eye on the couple watching the waves crash against the beach, and the other firmly fixed on the seagull that might be about to ruin their fish and chips. 8/10 Tristan Gatward bed for a roboticised vocal that reflects the depersonalising effect of a toxic relationship. The guitars on ‘Nephews’, on which she dreams of being with her relatives “under the sea”, simulate the wash of water.

The project was birthed from the open mic nights Margolin used to play, and there’s a clear sense that she’s the ringleader as she revels in the noisy energy of her bandmates. The dual vocals on the jittery goth pop of ‘Don’t Ask Me Twice’ are a case in point.

If it’s taken a long time to release their first ‘proper’ album then it was worth the wait, despite Margolin’s warning shot on ‘Homecoming Song’ that, “there’s nothing inside.” 7/10 Susan Darlington

Porridge Radio — Every Bad (secretly canadian) The key line on Porridge Radio’s debut album arrives on ‘Lilac’. “I don’t want to get bitter / I want us to get better,” wrestles the Brighton quartet’s Dana Margolin over slacker indie instrumentation. It encapsulates the record’s drive towards self-understanding, which frequently sees her repeating phrases until she either believes in them or they can no longer harm her.

These mantras teeter towards the confessional but pull back by dint of her delivery, which rages with the power of conviction and a lack of self-pity. The lo-fi grunge of ‘Sweet’, for instance, centres on a conversation between mother and daughter. “And are you still so depressed?” one asks the other futilely but firmly, having exchanged gifts.

It’s an attention to detail that extends to the music, despite it being superficially punky in approach. The long, cool synth lines on ‘(Something)’ form a The Chats — High Risk Behaviour (bargain bin) At the end of 2017, a grainy YouTube video of a track by The Chats song ‘Smoko’ went viral. Three lads, three chords, one very striking mullet. Like the mullet in question, bad taste is central to the debut album by the Australian punk rock trio: a lot of the focus is on getting wrecked, and there’s no problem too large that a trip to the clap clinic can’t sort. But of course, it takes a hell of a lot of intelligence to make music this dumb. As hook writers and storytellers, The Chats are masters of economy – frontman Eamon Sandwith may be singing about the full fat pleasures of life, but the medium is as sparse as you like. With no funny business, sixteen songs manage to collectively limbo under the half an hour backdrop. Sonically, they’re painting in the scuzzy power-pop colours of Buzzcocks, The Hives, even Sham 69. And taken in that spirit, High Risk Behaviour is a huge amount of fun and does exactly what it sets out to. They celebrate the best of times (having a really nice pub meal with plenty of ketchup in ‘Pub Feed’) and commiserate the worst of times (‘Identity Theft’ bemoans when your bank details are stolen buying drugs on the dark net). Stick it on at 5pm on a Friday. I dare you. 8/10 Fergal Kinney

Yves Tumor — Heaven to a Tortured Mind (warp) After this fourth album and second for Warp, we are still none the wiser about exactly who or what Yves Tumor is. Opening track ‘Gospel For a New Century’ comes in on a bed of scratchy horns, rolling drums and stoned vocals, but with a clear sense of forward momentum. It is a single, a standalone tune, a bastion of focus and thrust that has not been typical of Tumor’s previous work. Could this be, we ask ourselves, a sign of a more straightforward RnB record?

Our questions are answered within seconds of following track ‘Medicine Burn’, with its squalling, compressed guitar tone and nonsensical, pain-ridden lyrics. We are firmly back in the deregulated zone where confusion is king. This is the pattern of Heaven to a Tortured Mind; a give and take between challenge and payoff.

The payoffs don’t come bigger than on ‘Kerosene!’; a five-minute slick, seductive two-way between Tumor and an unnamed female singer that launches into ecstatic, skyscraping, Prince-esque electric guitar solos at multiple points. It is an irresistible track, the biggest moment of his career to date and proof that he could be a major overground star one day if the notion were ever to interest him.

But evidently, as of now, that is not the plan. There are too many simultaneous ideas, too much comfort in saturating the sound palette throughout Heaven to a Tortured Mind for it to have mass appeal,

and yet it is that very freewheeling experimentation that makes it such an intoxicating listen. A little like the moodboard records of recent years by Thundercat, King Krule or Gonjasufi, the power here comes from the constant ambush of new ingredients, all unified by the connective tissue of its auteur’s musical personality. Genre identification is redundant in the face of this level of artistic freedom. Together with 2018’s Safe in the Hands of Love, this album represents the imperial phase of Yves Tumor’s career, him out at the vanguard of the world that he himself created. Only he can know what happens next. 8/10 Max Pilley emotions, the record is at times defiant, at others tender, but always imbued with an understated kind of strength. The sparse, solemn closer ‘Memories of Winter’ breaks the spell somewhat; a reminder of the inevitable emptiness left behind after a relationship is over. 7/10 Katie Cutforth

Dana Gavanski — Yesterday Is Gone (full time hobby) Heartbreak is a well-trodden topic in songwriting, but Canadian singer-songwriter Dana Gavanski manages to make it her own on a confident and compelling debut LP, Yesterday Is Gone. Born in Vancouver to a Serbian family, Gavinski began to write music in Montreal during her final year of college, when she picked up a guitar left behind by her ex-partner.

Yesterday Is Gone is more than a title – it’s an imploration that sustains throughout the record. “I’m learning how to say goodbye,” sings Gavinski on the title track, “to let you go and face the tide / To wrap my feelings in a song.” Produced alongside Sam Gleason and Mike Lindsay of LUMP, the record explores the muddiness that comes with breaking up; Gavanski’s attempt to discover and understand herself outside of the relationship, and ultimately, to move on from it.

Her vocals have a sweet soulfulness reminiscent of Julia Jacklin, tinged with occasional touches of dissonance that bring to mind Cate Le Bon. Working through a plethora of Sports Team — Deep Down Happy (island) 2019 was a hell of a year for Sports Team. Labelled ‘everyone’s new favourite band’, they set about delivering on that tag with a trail of feverish live shows where everyone was literally invited. And so, from bussing fans to Margate and headlining stages at festivals, to impromptu gigs at their local, that scattergun exuberance hits with the same velocity here on their debut.

Everything is packaged into tight 3-minute bursts as you hurtle through The Maccabees-esque ‘Here’s the Thing’, pick up a few Brexit tropes on ‘The Races’ and unpack “I just wanted to be your Demi Moore” on ‘Kutcher’. Opener ‘Lander’ also punches straight in as vocalist Alex Rice instantly establishes his part-Mick Jagger/part-Eddie Argos persona—and he proves to be the lightning rod throughout, shouting, straining, strutting his way through tracks, snapping sardonic lyrics like, “This avant garde / Is still the same / Go to Goldsmiths and die their fringes to know they’ve made it only / When they’ve signed their rights to Sony”. Ironically, it’s the kind of quintessentially British indie pop that Transgressive might have signed up in their seat-of-the-pants genesis, and it’s that sense of loose ties and loose limbs that gives Deep Down Happy its endearing nostalgia of spilling into the streets for sunshine pints before ending up in a club, a stranger’s front room… or another bus to Margate. A debut as wry, energetic and charismatic as their inexhaustible live presence has always promised. 7/10 Reef Younis

Daniel Avery & Alessandro Cortini — Illusion of Time (phantasy) Ever since he ditched his Stopmakingme name at the start of the last decade, Daniel Avery has been on the move stylistically, and his latest release marks his biggest deviation yet. The shift from big-room techno towards textural abstraction that he hinted at with his last solo album goes full-blown for this collaborative album with Nine Inch Nails keyboardist Alessandro Cortini, in which neither a kick-drum thud nor snare clap is encountered across its 45 minutes and yet still the signifying aesthetics of club music – nocturnal yet bright, solitary yet communal, with interplay of tension and release – linger. Added to that beatless atmosphere is a laudable embrace of sonic grit and grain alongside the sort of wistfully poignant grandeur more often deployed in stadium rock. The result is a record that suggests Godspeed You! Black Emperor in drone mode, reimagining Music For Airports as if the runways were covered in gravel and air traffic control was on strike.

Most of the time, this works a treat. Opener ‘Sun’, with its overpowering tape hiss and decayed brushstrokes of distant synth tones, sets a widescreen cinematic scene that, despite only containing two chords for its entire duration, retains enough tactility to avoid boredom. Similarly, the fetishisation of surface noise and analogue crackle on ‘CC Pad’ generates an atmosphere that complements the gently undulating synth, and the neon oscillations of ‘Enter Exit’ provide a perfect foundation for the piece’s climactic feedback section.

More interesting still are the moments in which Avery and Cortini prefer slow builds to simple repetition: ‘Inside The Ruins’ mines the aggression of industrial techno, but, with the music stripped of any movement, the emphasis becomes one of pure, relentless pressure. Equally, ‘Water’’s exercise in disintegration evokes a come-down for the club itself, as if the echoes of a once-euphoric space are being slowly unravelled layer by layer. Much of Illusion of Time feels simultaneously improvisatory and studied, which perhaps betrays Avery and Cortini’s working process: the record was built via email over several years, and then put to bed in a single three-hour session while the duo were on tour together with NIN. Indeed, that depth is one of the album’s great strengths: even when the pair edge into the more unabashed heartstringtugging realm of soppy shimmering guitars, there is enough three-dimensionality and conceptual heft to guard against potential mush, leaving a record of pleasing contradictions: brittle but dense, machined but organic, constantly mutating and pleasingly still. 8/10 Sam Walton

Thundercat — It is What it Is (brainfeeder) Since his break-out collaboration with Kendrick Lamar on his 2015 masterpiece To Pimp A Butterfly, which built upon the considerable reputation he’d garnered through his work with Flying Lotus, Suicidal Tendencies and others, Thundercat has swiftly graduated from a musician’s musician to a listener’s musician, culminating in the success of his last album, 2017’s Drunk. Drunk elevated Thundercat from the pre-eminent session musician sought for his ferocious 6-string bass virtuosity and funkadelic groove to his own singular and commercial force. However, despite the jovial verve of Drunk, Thundercat cut a sullen and paranoid figure on the record when listening closely.

This pervasive gloom is a hangover from his first two albums, The Golden Age of Apocalypse (2011) and Apocalypse (2013), both of which were introspective affairs soaked with moments of disquiet. Thundercat being Thundercat, there was fun to be had on both records, such as the intoxicating ‘Oh Sheit It’s X’ and the Boys Noize bounce of ‘Jamboree’, but these tracks were mostly diluted by surrounding waves of consternation.

If his first two albums were crepuscular ruminations, then Drunk was the other side of the coin – the subsequent, pain-numbing blow-out. It saw Thundercat trade in meditative jams for truncated spats of energy and drowned the pensive with deluges of sanguinity and irreverence. However, like a sicklysweet cocktail, while the first sips were rich with the taste of funk and California sunshine, by the end of the album you encountered where all the bitterness was congealed and Drunk finished with a nuanced capitulation; a hallucinatory and fragmented solace that hit as hard as any of his earlier albums.

Thundercat seeks to cement this dexterity further in his new album, coming hot off a successful collaboration with Brainfeeder labelmate/owner Flying Lotus on the latter’s 2019 album Flamagra. However, the results on It is What it Is are frustratingly uneven as mature craftsmanship and heartfelt attempts at transcendence are continually herniated by misplaced Drunk-era interludes that downplay the emotional weight of the record and occasionally border on the obnoxious.

Following a short solipsistic cosmic intro, the album starts auspiciously with the orchestral gloss of ‘Innerstellar Love’. It’s a track packed with a full-bodied and erratic drum that tears through the doting bass before submitting to the fashionably-late sax that envelopes the sound of the track and conjures a swirling Sun-Ra tainted black hole.

The celestial strings at the start of the punk-driven roar of ‘I Love Louis Cole’ quietly melt to a profane charge of drums that are punctuated by hi-hats, all the while Thundercat channels tales of hedonistic nights until the song buckles into a drowsy introspective sound. It’s a rare instance where Thundercat is able to alchemise euphoria and stupor within one track and it is a raging success. Drunk’s extroverted funkiness surfaces in ‘Black Qualls’ where Thundercat pays homage to his musical influences, featuring funk legend Steve Arrington alongside Childish Gambino and Steve Lacy. Lyrically, Thundercat shines here as he intersperses potent truths of upwards mobility as a young black man in-between all the infectious bass.

After a polished start, Thundercat then abruptly up-ends the record by going on a tear of uninspiring and flimsy tracks consisting of ‘Miguel’s Happy Dance’, ‘How Sway’, ‘Funny Thing’, and ‘Overseas’. Each feels blotchy and incomplete, and doesn’t manage to achieve the connection you feel Thundercat’s desperate to make. Worse yet, it stalls all momentum and irrevocably upsets the spiritual equilibrium of the record.

The album is briefly able to recalibrate sonically during ‘Dragonball Durag’, with a deep sumptuous bounce before stalling again with pretty but ultimately dull ‘How I Feel’, before winding into the didactic and innocuous Beatleesque oddity of ‘King of the Hill’. It’s only when Thundercat drops the zaniness that the album connects again with the vulnerable soul of Unrequited Love; lacing the yearnings of a remorseful Thundercat with a cutting violin sailing above it.

The reflective ‘Fair Chance’ is undoubtedly the highlight of the album, combining an aching sincerity with a sonic contrast from the rest of the album thanks to appearances from Ty Dollar $ign and Lil B. Narrating over a sombre atmosphere, Thundercat is at pains to explain how he tries to “get over it, to get under it” – “it” being the death of close friend Mac Miller. The interplay between the three vocalists strikes a spiritual chord that soars above the rest of the album. However, despite this resuscitation, it’s too little too late to entirely save

the record, and album closer ‘It is What It Is’ bows out in confused fashion.

The majority of the album’s minutes are filled with gorgeous musicianship and compelling lyrics, but the album never recovers from its lacklustre middle section. It is what it is. 6/10 Robert Davidson

Baxter Dury — The Night Chancers (heavenly) Stanley Kubrick once said that a film is – or should be – more like music than fiction. It should be a progression of moods and feelings. He also believed that observation is a dying art. The parallels between Baxter Dury – whose music is synonymous with selfdisclosure and character scrutiny – and Kubrick are more visible than you’d think. The Night Chancers’ conscious progression is a nod to Kubrick’s psychological journey through the maze scene in The Shining. Atypically for Dury, not every song here is confessional. Instead, they’re more of a feeling projected into a filmic narrative. On some of the tracks, different characters appear, and we know that because Dury adopts different voices and accents to fit the situation. The casual darkness of Dury’s lyrics and the upbeat music is a contrast that becomes almost comical, echoing Kubrick’s introduction of bleak irony to the sublime and absurd. On this record, Dury remains disarmingly, brazenly British. It’s the insular safety of middle-class London that permeates The Night Chancers: from the title track’s thrilling affairs that dissolve into sweaty desperation to the absurd bloggers of ‘Sleep People’. There are stories about the futility of clinging to the fag ends of the fashion set via soiled real life (‘Slum Lord’), social media-enabled stalkers (‘I’m Not Your Dog’), and sleepdeprived optimism (‘Daylight’). The record’s finely-drawn vignettes are all informed by the corners of the world Dury has visited, but its overarching theme is that of being caught out in your attempt at being free.

There is a political undercurrent to Dury’s music, but it’s the intimate details of everyday domestic life that get him going. The title track is a case in point: an Anglo-aggro ode to the aspects of British life that no one talks about, recalling Mark E. Smith’s ability to make the ordinary sound extraordinary. Indeed, Dury is a bit of a wordsmith, but in a way that doesn’t alienate anyone. It’s matterof-fact, anti-intellectual even. Above anything else, Dury shows us that a little bit of melody and a lot of honesty can go a long way. 8/10 Hayley Scott

Jackie Lynn — Jacqueline (drag city) Let it never be said that Haley Fohr doesn’t know her way around an engaging alter ego. Following up her debut release under the Jackie Lynn moniker back in 2016 – and a wildly successful second foray into what-used-to-be-called freak folk as Circuit des Yeux – Fohr defies the notion that either project should pin her down with Jacqueline, ostensibly a concept which follows the daily life of our titular picaro, a femme long-haul truck driver, from casino to Odessan bar, with an incongruous debt to electric disco as audacious backdrop; filling station Americana as high camp, a few hundred yards apart from her previous work.

This is all to say, as conceptually robust as Jacqueline might be – from the Moroder-worship of ‘Casino Queen’ to luscious comedown ‘Traveler’s Code of Conduct’ – following the vague narrative won’t come close to the sheer joy of the sound. Fohr may be one of the sole artists capable of undergoing genre exercises with the same pro appeal as her more ‘serious’ output. ‘Shugar Water’ is one of her most pop-minded numbers to date (think Nico fronting Talking Heads twisting their way through an ABBA deep cut), but far from cheapened by Fohr’s enduring weirdness. That’s Jacqueline; one of today’s most outlandish artists attempting a wider connection, ironically projected through a sparkling face mask. 8/10 Dafydd Jenkins

Sabina Sciubbia — Force Majeure (goldkind) There aren’t a huge number of comparisons you can instantly drag out of your brain’s musical hyperspace when an album begins with a glistening chamber-pop groove and Sabina Sciubbia’s thick, Nico-infused atonal vocal singing “I’m dancing with the clouds / romancing with the clouds”. Best known for her role fronting Grammy Award-winning Brazilian Girls, her own solo rebirth (Force Majeure being the first full-length under her own name in six years) sounds fresh and exploratory, excellently sidestepping being a retrogressive throwaway whilst still paying homage to the scenes that birthed it. Sciubbia’s explorations sprint over a remarkable ground, but never risk nearing saturation point: twelve tracks ease through chamber pop, baroque, italo-disco, N.Y. East Village bossa nova, electro and punk, flicking between French, Italian, German and Englishlanguage when one dictionary’s parentheses fail to translate her intent.

The first four foot-tappers nod to the free-form pop of Sciubbia’s time at the Nublu Club with the Wax Poetic and Nublu Orchestra. ‘You Broke My Art’ reaches further still to the highlights of Stereolab’s art-rock bossa nova, whereas ‘Stars’ sounds like an off-kilter ode to Robyn’s ‘Honey’ (it’s literally about stars

falling from the sky and lovers setting them on fire). Even the transition from a more leftfield Can-plays-The-Normal bleep to a Marlene Dietrich-esque, tender musical chanson doesn’t sound forced as it climaxes with fears about over-sharing an identity (‘I Know You Too Well’). And as soon as the theory gets heavy, there are still enough lyrics on the album to be written on a passive aggressive tote bag. It’s serious, often numinous soul-searching, sure, but you can still enjoy it: “All I want, all I need is love, and coffee too.” 9/10 Tristan Gatward The new Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs album is a visceral experience. The record is all guts and glory, tauter than before and all the better for it. It’s relentless; an all-out-assault of riffs and rumblings that pushes Pigs x 7 to new heights. 8/10 Liam Konemann

beats and slicing guitar lines cut to the bone.

Hinds’ music will always be charming in its juvenility. It is, to an extent, an indie expression of a teenager in turmoil. Yet on The Prettiest Curse, the band have honed their craft: here their characteristic puerility slashes like a knife, and is wielded as a weapon in the pursuit of inclusive, jubilant, defiant indie-pop. 9/10 Rosie Ramsden

Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs — Viscerals (rocket recordings) Despite their frankly excessive band name, Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs know not to overstay their welcome when it comes to albums. While two songs on 2017’s Feed the Rats were over fifteen minutes long, you can get away with that when your record only has three tracks on it. Likewise their 2018 breakthrough King of Cowards, which capped proceedings at six songs. Now their third album proper, Viscerals, comes in at eight tracks – one of which, unusually for them, doesn’t even hit the two minute mark. Pigs x 7 aren’t messing about here. Viscerals is a much tighter record than the band’s previous efforts. It can be difficult to avoid sacrificing depth in the pursuit of a leaner sound, but nothing is lost here. Lead single ‘Reducer’, for example, is an absolute onslaught of riffs and blistering vocals, while the one-anda-half-minute long ‘Blood and Butter’ momentarily breaks up the pace with a deeply unsettling spoken-word account of the ‘social pressure cooker’. Meanwhile, the thrashing ‘World Crust’ and ‘Crazy In Blood’ ensure that Viscerals lives up to its name. Hinds — The Prettiest Curse (mom + pop music) Hinds’ third album is not only the band’s most candid and unapologetic to date, but its revolutionary spirit speaks to their departure from the lo-fi, fluffy indie-pop of their 2016 debut, Leave Me Alone. While admittedly there is still a good amount of fluff here (the album is littered with upbeat tracks that could elicit the desire to dance in more or less anyone) The Prettiest Curse is an evolution. It is striking, complex, uncompromising indie-pop. More than that, it makes a bold statement: it canonises Spanish indie-rock, bringing the Spanish language, in which the band embrace singing for the first time, into the Anglophone mainstream of the genre. The Prettiest Curse is a celebration of women – of Spanish women (the album artwork was designed by legendary photographer Ouka Leele) – and is, at its heart, about the intricacies of women’s emotional experiences.

Musically, Hinds layer dizzying samples with trippy distortion and candy floss vocals. Lead single ‘Riding Solo’ sees the four-piece channelling MIA’s intoxicatingly visceral playground pop in a bittersweet ode to isolation and loneliness. ‘Boy’, on the other hand, transitions seamlessly between English and Spanish to create an anthemic, crescendo-laden track that screams intense desire. Elsewhere on the album, classical guitars provide the backdrop for sultry vocals, while in later tracks statement drum

Ultraísta — Sister (partisan) Ultraísta are a supergroup of sorts, made up of Beck and REM’s live drummer Joey Waronker, wispy electro-pop singer Laura Bettinson, best known for her work as Femme and Dimbleby & Capper, and long-standing Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich, who has guided Thom Yorke and co through every album of theirs since OK Computer. Of those three, it’s Godrich’s fingerprints that appear to press heaviest on Ultraísta’s second album: the skittering beats are sliced and diced with the sort of beautifully uncanny human–android push–pull last heard on In Rainbows, and pleasingly textural and three-dimensional synth tones create an engrossing soundworld of electronic fuzz over which Bettinson can layer her glacial coo.

What’s missing, unfortunately, is anything resembling a memorable melody: vocal lines are treated more like looped samples than songs, and the result is a series of almost identically (although evidently painstakingly) constructed edits of studio jams that are impeccably tasteful, immaculately crisp, and disappointingly sanitised. Flickers of life are audible in ‘Water In My Veins’, ‘Bumblebees’ and ‘The Moon and Mercury’, where Bettinson is allowed a degree of looseness in performance, stretching out the arrangements

to create some much-needed space, but otherwise Sister is too often hamstrung by its cold, audiophile perfectionism. On the one hand, this is dazzling to encounter – the entire album gleams sonically, every edit feeling super gourmet with nary a hair out of place –but on the other, such airtight cleanliness leaves Sister frustratingly gutless; a masterclass in studio production technique in desperate need of songwriting calibre to match. 6/10 Sam Walton too: check the percussion on tracks like ‘Version’ and ‘Boy’, swelling like a militia until they’re very front and centre, the last noise on the battlefield. 7/10 Fergal Kinney

‘SLEEPN’, the sonic avalanche of ‘NO 1 ELSE’, and the cathartic ‘UPP’.

Unfortunately, the record hangs around a couple of tracks too long, with the incongruently ebullient ‘LICK IT N SPLIT’ and gratuitous ‘EXIT 2 VOID’. This marginally nullifies the record’s impact, but it’s otherwise an accomplished, confident, and virile work. 7/10 Robert Davidson

FACS — Void Moments (trouble in mind) On the third album from the Chicago post-rock trio – formed from the ashes of Disappears in 2017 – singer Brian Case is almost disappearing into their hypnotic wall of industrial sound. Minimalism has always been central to the FACS project, but here Case is almost actively removing his voice from the equation – there are snatches of cut-up vocals in the early part of tracks, and then nothing for quite some time until the next one. It’s highly effective, suggesting that he wants us to know that what he’s saying isn’t at all the most important thing going on here. Except, well, when it suddenly is. ‘Casual Indifference’ sees this technique deployed to detonate a political message: “Different sexes,” spits Case, staccato, “Playing around with... Who can say?”. In its elusiveness and its repetition, it becomes a remarkably effective bit of messaging. Case explained that the track “is definitely the most explicit lyrically in terms of its message... love is love, and anyone who disagrees is wrong.” Right on.

In their hypnotic, repetitive moodiness, the band’s closest analogue is probably Salford’s GNOD, or even Thurston Moore on his last two records. The drumming is worth mentioning Zebra Katz — LESS IS MOOR (zfk) It takes LESS IS MOOR, rapper Zebra Katz’ long-anticipated debut album, about ten minutes before it becomes distressingly twisted.

Early tracks ‘INTRO TO LESS’, ‘ISH’ and ‘LOUSY’ serve as potent warnings: taut with an unstable, macabre energy and cavernous beats which regularly explode with a disorientating fuzziness. All the while Katz’s composed flow proclaims his intention to keep the dance floor jumping. By fourth track ‘BLUSH’, Katz’s lurid grooves are decidedly off the rails, emitting an ominous intensity like a chthonic Faithless.

From hereon in, the album goads you into dancing like moribund Saint Vitus victims with the infectious up-tempo swing of ‘IN IN IN’, the eviscerating drum ‘n’ bass ferocity of ‘ZAD DRUMS’, the brooding, HEALTH-like ‘MONITOR’ and the industrial-driven ‘MOOR’ on which Katz’s flow briefly disintegrates as the nocturnal chaos consumes him in carnality and comedown paranoia.

The fabric of this middle section is unsettlingly versatile, as Katz contorts it with an occult majesty. His lyrics expertly oscillate between fleeting hedonic fervour and pointed societal rage to fuel an insidious, isolating sound. ‘NECKLACE’, an acoustic cut, comes as a much-needed reprieve that showcases Katz’s tenderness, momentarily liftinh the pervasive darkness before entering what feels like a satisfying closing stretch: the pulsating drive of

TOKiMONSTA — Oasis Nocturno (young art records) In 2015, TOKiMONSTA lost the ability to hear music. After two sets of brain surgery to treat Moyamoya, a life-threatening brain disease, music lost all melodic meaning for the LA producer, also known as Jennifer Lee. Despite the trauma of this incident, her recovery was swift and successful: she played Coachella just four months after her surgeries and became the first Asian American producer to receive a Grammy nomination for the best dance/electronic album in 2017.

Oasis Nocturno follows 2017’s Lune Rouge, an album entirely composed of songs that Lee wrote while recovering her musical sensibilities. This new record is similarly moving and can be understood as Lune Rouge’s second act, another step along her journey of recovery and reclaiming her narrative.

Echoes of the last few years’ events ricochet throughout this album. These can be traced through ‘Up and Out’, a track that takes its time, to the tender and sensual ‘Phases’, to the album’s closer ‘For My Eternal Love Dream, My Treasure’. The latter transmits a feeling of relief – of having said your piece, even if no one will ever hear it.

The album’s features are lengthy, and certainly have their extraordinary moments; EarthGang’s rap on ‘Fried For

The Night’ is a highlight of the album. Elsewhere though, they feel like they compromise Lee’s true production abilities, squashing the instrumental to make room for the vocal feature. Oasis Nocturno is an emotive spin on nu-hip hop, cementing TOKiMONSTA’s auteur-like relationship with the mainstream. 8/10 Jemima Skala

Waxahatchee — Saint Cloud (merge) Anybody familiar with Katie Crutchfield’s last record could have predicted that she’d have some serious healing to do on the follow-up. Out in the Storm was a noisy, aggressive exposed-nerve of an album, one wrought with trauma, and the typically relentless touring schedule that followed served as an extended process of bloodletting. At the end of it, in the summer of 2018, Crutchfield embraced sobriety.

It was a decision that set her up for a series of homecomings on Saint Cloud, her fifth record as Waxahatchee. With drink and drugs eschewed, she’s returned to the clear-eyed outlook of her teens, and to the musical landscape that defined her upbringing in Birmingham, Alabama. The influence of country giants like Emmylou Harris and Linda Ronstadt hangs heavy over the album, but Lucinda Williams is the most significant reference point; not just in terms of the bright and breezy Americana of the tracks, but in the way she evokes Car Wheels on a Gravel Road by painting such vivid portraits of her travels across America. There’s late-night drives across the Midwest on ‘Fire’, reckonings with their past in her hometown on ‘Arkadelphia’ and a nod to her father’s Florida heritage on the title track.

Producer Brad Cook was Crutchfield’s primary collaborator on Saint Cloud, but the real masterstroke was recruiting Detroit group Bonny Doon as her backing band – they bring such nuanced lightness of touch to the tracks. The tumult and churn of Out in the Storm must now feel worth it: this stunningly pretty ode to recovery is Crutchfield’s finest work, and possibly her masterpiece. 9/10 Joe Goggins

Sorry — 925 (domino) While Sorry may not be oversharers in interviews, over the past three years the opposite has been true with their music. School friends Asha Lorenz and Louis O’Bryen, the duo at the nucleus of the project, began making music in 2014. From 2017 onwards – now christened Sorry after going under the name FISH for a bit – they have dispensed a steady trickle of demos, singles and audio/visual mixtapes that has rarely paused. However, 925, their debut album proper, presents an opportunity for the north London outfit – important to distinguish that since they’re often grouped with the ‘south London’ scene spearheaded by Goat Girl and Shame – to take stock.

But that’s not what they’ve done. Or, at least, that’s not what it feels like they’ve done. The pair have spoken in the past about how while superficially they’re considered to possess all the normative tickboxes of a guitar band but that their approach is more akin to a spontaneous bedroom producer: write it, cut it, share it. Above anything, 925 retains that instinctive feel; maybe that’s because they shunned a grand studio and made it at home.

Consequently nothing here is overly ponderous. Songs are moments. Scenes. Sometimes they’re about dreamtup characters like the opener ‘Right Around The Clock’, Louis singing “she’s all dolled up like a movie star”. Other times it’s tongue-in-cheek comments on clichéd excess: “I want drugs and drugs and drugs” on ‘More’. Musically it all feels distinctively, and refreshingly, out of step with the current proliferation of politico-postpunk. The sound has more in common with the mechanical thrust of Garbage’s ‘Version 2.0’ or The Cure’s Japanese Whispers than anything off, say, Schlagenheim. These are songs built around sizable melodic choruses, but still manage to be idiosyncratic – like Asha’s vomiting “yuck” utterance on ‘Starstruck’, the unexpected, bass-powered swerve ‘Wolf ’ takes or the joyful theft from Louis Armstrong’s ‘What A Wonderful World’ that distinguishes ‘As The Sun Sets’.

Sorry also deliberately invite listeners’ projections onto their songs: “genderless” is how Asha recently described her creations. A sad pretty love song like ‘Heather’ perhaps captures that best, Asha and Louis trading lines: “what’s a boy to do / what’s a girl to do?”. Same goes for ‘Snakes’: “I never thought about you in your underwear,” sings Asha. “Because I never really cared what was under there.” And while a debut album represents a significant chapter in any band’s book – and this is a really good one – you get the sense that Sorry are comfortable with the notion of change: that tomorrow they might be something different. 8/10 Greg Cochrane

Flat Worms — Antarctica (god?) Though the term ‘supergroup’ can sometimes carry with it some degree of misplaced expectation, L.A. trio Flat Worms have always felt exempt from such a predetermined fate. Not only has

their Petri dish of psychedelia-saturated post-punk been devastatingly potent in recent years, the band’s cohesive framework has proven them to be far more than some throwaway side project.

Scooped right from the barrel of John Dwyer’s fabled Castle Face Records, Flat Worms’ personnel partly make up the ranks of Thee Oh Sees, Ty Segall Band and Dream Boys. With all three members’ playing careers easily linked by connectable dots, Flatworms’ output feels distinctly unforced and organic. The band’s third full-length effort, Antarctica is a chaotic vision of the mundane; one that makes no attempt to stifle the sarcasm of its commentary.

Recorded in just six days inside Steve Albini’s Electrical Audio studio, Antarctica trades washed-out production for the sort of steely-faced surfaces in which you can see your bloody-nosed reflection as it batters you to a mangled pulp. Laying each apathetically recounted decade to landfill, ‘The Aughts’ is an exhausting sprint to the finish line. Chugging basslines and razor-sharp guitar riffs lacerate lead single, ‘Market Forces’, whilst the title track clings to the sort of dryly-spoken nihilism of any sure-fire satire. 7/10 Ollie Rankine its door to the listener. Complete with a persuasively smooth riff, ‘Cold Light of Day’ comes as a counter to the album’s cold start. Arie van Vliet then channels the dry wit of Bill Callahan on ‘At Lunch’ – an unrushed ode to day-drinking – before the lolloping ‘Trained Eye’ builds a hypnotic mood. The Velvet Underground’s influence can be felt through the whole album, but this wiry song is particularly indebted to the school of Lou Reed.

The pace quickens again on ‘From Never to Once’, another track on which the guitar riffs sound pretty crass until they’re repeated enough. The band are unflinching in the album’s most hectic moments, revelling in the trainlike rhythms of ‘Through the Garden’; equally, Shalita Dietrich’s subtle bass create a sense of calm on ‘Jacob’s Ladder’, before album closer ‘Standard Procedures’ disintegrates.

Lewsberg’s iconoclastic approach to their music is in keeping with their Sonic Youth and VU role models but also holds them back on In This House: an intriguing record which impresses with its repetitive, unpredictable nature while still feeling slightly unfinished. 5/10 Jamie Haworth New Rave movement with Klaxons and short-lived project Shock Machine.

There are traces of his past work on the album – notably the woozy Tame Impala-isms of ‘Devil Is Loose’. For the most part, though, he guides his introspection firmly through ’70s influenced singer-songwriter territory.

‘See The Monster’ borrows from the psychedelic atmosphere of Lee Hazelwood’s ‘Some Velvet Morning’, the ode to his daughter ‘Edie’ finds him slipping into a lounge suit to play piano, and the instrumental saxophone interlude ‘Lessons In Dreamland Pt. 1’ tests the water in a smoky nightclub.

Part recorded in Bryan Ferry’s studio, Righton seems to be styling his post-band career on the former Roxy Music frontman. This results in a sophisticated album that nonetheless lacks the visceral thrill of a true performer. 6/10 Susan Darlington

Lewsberg — In This House (cargo) As a word of warning, the opening track on Lewsberg’s new record is not enjoyable. Arie van Vliet’s intermittent vocals are buried deep in the mix on ‘Left Turn’, crowded out by harsh, standoffish guitar chords as the singer only half tells an incoherent story. “Keep on listening – or don’t” seems to be the message from the Rotterdam-based band.

Thankfully, though, In This House – the second album from this art rock, lo-fi nihilist outfit – does eventually open

James Righton — The Performer (deewee) The title track of ‘The Performer’ finds James Righton mulling over the conflict between creative and family life. “That’s not me standing there, in the light / Put [the artistic persona] on for the night,” he croons over a piano line that sounds suspiciously like Foreigner’s ‘Cold As Ice’.

It’s a theme that permeates his first solo album, which sees him settling a little uncomfortably into his mid-30s after a youth spent at the forefront of the Mentrix — My Enemy, My Love (house of strength) Having been born in Iran and lived in Berlin, France, and the UK, Samar Rad’s life experience makes her something of a poster woman for these warmongering modern times. After moving to France as an 8-year-old to escape war in Iran, she moved back at 14, relearning Farsi practically from scratch and switching from studying Latin and French literature to Arabic and the Qu’ran.

These “existential wanderings” (as Rad calls them) have ultimately shaped her polyglot sound alongside Persian poetry, traditional instruments and the inward-looking contemplation of Sufism. It gives ‘My Enemy, My Love’ a spiritual existentialism that enables a track like ‘Longing’ to take a Mooyeh mourning chant from Iran and spin it

into all-engulfing Fever Ray darkness or allows you to imagine the opening of ‘Nature’ getting dropped into The Prodigy’s ‘Smack My Bitch Up’ as the easterninspired interlude.

They might be slow-burning, patient tracks but Rad’s use of rhythm and mysticism maintain that beguiling presence. It’s a combination that comes to life on title track, ‘My Enemy, My Love’ as Rad uses a daf (a large hand drum with metal ringlets) to crash out a tempo that’s propulsive, industrial and ancestral all at the same time; elsewhere, ‘Loyalty’ takes a similarly percussive approach, but refines it to a simpler marching drum mantra.

That introspection and worldview paired with dark electronica and traditional Iranian melodies make for a fascinating, if complex, listen that pushes beyond convention. And it’s that melting pot strength that makes this one worth digging deeper, wherever you’re from. 6/10 Reef Younis

Pottery — Welcome to Bobby’s Motel (partisan) Welcome to Bobby’s Motel is one of those debut records that wears its influences proudly. Every few seconds, something in it will give a little tickle to your mental music archive; it could be a vocal intonation or a lyric, a bass strut or a production flourish. For the subsequent few moments, the track unfurling before you is vying for your attention with your innate desire to identify exactly which Talking Heads or Devo track it rhymes with. Whether that experience sounds like a fun game or some kind of torture will likely dictate your reaction to this album.

The track ‘Bobby’s Forecast’ alone runs a gauntlet of historical trends, from the ESG/DFA cowbell rhythms that set it in motion to the deep, funk-rock groove that forms the song’s backbone to the James Brown “c’mon, break the drummer’s arms” exaltations of vocalist Austin Boylan as it breaks down. The sludgy psych of the title track, the Bryan Ferry sophisti-pop of ‘Reflection’, the Nick Cave drama of ‘NY Inn’, it’s an entire day’s BBC 6 Music running order in less than 40 minutes.

Deeper subject matter is rarely easy to discern, save perhaps for the climate change-conscious ‘Hot Heater’, but in truth, Welcome to Bobby’s Motel is an endlessly re-listenable album, and fans of post-punk and new wave will find many joys in its contents. If there truly is nothing new under the sun, is it really such a crime to create such a loving facsimile of a model that works so well? 7/10 Max Pilley everything from sorrow to nostalgia, anxiety to joy.

A Western Circular plays host to an impressive line-up of guests, featuring vocal contributions from Samuel T. Herring of Future Islands, Sudan Archives and Laura Groves. These collaborations have formed and developed over a number of years, the end result being a project which is as ambitious and far-reaching as the soundscapes Archer creates. 8/10 Katie Cutforth

Wilma Archer — A Western Circular (weird world) Having released material as Slime between 2010 and 2017, composer, producer and multi-instrumentalist Will Archer has taken on a new pen name, Wilma Archer. A Western Circular is his debut LP under this new alias, representing a shift in his career. Inspired by the books of John Fante, the record aims high, exploring aspects of duality in the human condition: the ideas of life and death; peaks and troughs of emotion; finding beauty in pain.

The record moves dramatically between genres without feeling mismatched, emphasising Archer’s remarkable musicality and diversity as a composer. Two instrumental tracks open the record – the title track populated by sallow strings, and the smooth jazz of ‘Scarecrow’ – before MF DOOM comes in to speak the record’s first words. Archer expertly plays with tempo and layering, building a sonic world that induces NNAMDÏ — Brat (sooper records) That Nnamdï Ogbonnaya has chosen to shorten his stage name for the release of this latest record should not be mistaken as emblematic of a streamlining process more generally. Those familiar with the modern-day renaissance man, and specifically his 2017 LP Drool, can attest to the fact that he has a thrilling disdain for genre boundaries and does not set self-limiting parameters; accordingly, Brat, his first album as simply NNAMDÏ, takes in everything from hip-hop to low-key synthpop, via the occasional jazz freakout.

This is an album more indebted to his native Chicago than Drool, which took its cues from West African stylings in places, and the sense of greater musical cohesion that lends to proceedings is matched by a more singular thematic throughline than previously. Brat is an introspective collection, with opener ‘Flowers to My Demons’ – on which Ogbonnaya makes a pledge of self-care – setting the tone.

There’s still room for eccentricity, not least on the avant garde-meetsindustrial throwdown of ‘Perfect in My Mind’ or the nervy minimalism of ‘Really Don’t’, but the palette is largely one more clearly defined than on Drool. Woozy, late-night R&B reminiscent of Frank

Ocean or Sampha provides the backbone, in a manner that runs from the playful (‘Semantics’) to the profound (see ‘Glass Casket’, which provides the emotional axis for the rest of the record to revolve around). Like all of Ogbonnaya’s output, there’s a frantic energy to Brat that might prove a bit much for some, but there’s also evidence of a control to the chaos that makes this his most compelling solo release yet. 7/10 Joe Goggins horns across Birthmarks don’t coo or lull. They drool. They snarl.

But with all the exorcism comes a sort of ghostly release with the austere closer ‘There Is No Moon’, a fitting demonstration of Woods’ keen sense of pacing. “My dreams, they try and read between these lines,” she mutters, and all the tumult of the preceding seven tracks are granted a disquieting, if ultimately satisfying, ending. 8/10 Dafydd Jenkins ously like he’s fallen asleep on his MIDI keyboard, and stayed up ‘til 6AM perfecting each snare hit. So much excitement comes from this anarchic approach to sound selection and song arrangement; throughout, we’re left guessing what’s waiting around the corner. More often than not, it’s something wonderful. 7/10 Oskar Jeff

Hilary Woods — Birthmarks (sacred bones) For all the hard work Dublinbased composer Hilary Woods has done over the last few years, she’s yet to produce an album that ably straddles her twin sensibilities – as a mood-driven producer of tone poems, and a tantalisingly elliptical storyteller. Birthmarks, an LP two years in the making and a meditation on future uncertainty and childbirth, comes close to essential – but, recalling a black metal version of Cocteau Twins’ verdant collaboration with Harold Budd on The Moon and the Melodies, it also flexes the skill of its producer-collaborator, frequent dabbler in noise music and extreme metal, Lasse Marhaug. Where 2018’s Colt aped a little too much of Julee Cruise and Grouper’s obscured detachment – with songs like vague shapes suspended in moorland fog – Birthmarks not only denotes a figurative step forward but an almost literal one. The shape was a feral beast all along, and it’s sizing up the listener, every last blood-mottled hair now hyperreal, every yellow tooth sharp and hungry – see pseudo-instrumentals ‘Lay Bare’ or ‘Mud and Stones’, seamlessly folding into the resplendent folk-industrial stop of ‘The Mouth’, or the genuinely terrifying squall of ‘Cleansing Ritual’; the cellos and

Minor Science — Second Language (whities) A release from Minor Science, aka Berlin-based producer and writer Angus Finlayson, has long been a highlight of the Whities schedule. On debut album Second Language, he greets us wide-eyed and wonderstruck.

Both sonically and in terms of the record’s arrangement, there is a counterintuitive sense of precision to the chaos frequently on show here, many of the ideas having been crash-tested on previous EPs. This is one of the more intriguing facets of modern electronic music: the intricacy gifted from both evolutions in computer music and the melding of sound design and musicianship. While this release dabbles within those parameters, the music here is bright and vacuum-sealed - at times reminiscent of the digital gloss of Rustie or SOPHIE. But where those artists aim towards the truly synthetic, the music here feels like the soundtrack to a video game representing an organic world. On the other hand, ‘Blue Deal’ seems to be mimicking the familiar act of sampling from funk, but this reverse-engineered production style makes it sound joyfully cartoonish and uncanny.

This combination of skill and playfulness is present in tracks like ‘For Want of Gelt’, the extended drum fills toward the end of the track sounding simultaneMXLX — Serpent (kindarad) Matt Loveridge takes no prisoners on his latest record. The Bristol-based producer, songwriter and sound artist operates within the thick of the city’s burgeoning experimental and electronic music scene, having been a founding member of Beak> alongside Geoff Barrow and working with rising acts like Giant Swan and Scalping. Serpent is a record that testifies to the calibre of the creative company Loveridge keeps.

Like his previous LP as MXLX, the superbly-titled Kicking Away at the Decrepit Walls til the Beautiful Sunshine Blisters Thru the Cracks, this is a monster of a record, all leaden feet, oppressive weight and destructive power. Droning synths course through the body of each track, Loveridge’s half-spoken, halfchanted vocals contouring the otherwise amorphous instrumentation into something that feels surprisingly focused once you’ve adjusted to the gloom. There’s nothing here that quite measures up to the face-melting grunt of the previous record’s opener, ‘Your Bastard Mouth Is Open and Will Not Stop Howling’ – another absolute winner of a name – but the cumulative effect of Serpent packs just as much of a punch as that of its predecessor.

The Bristol underground scene is among the UK’s most exciting at the moment, and this album is yet another reason why. 7/10 Luke Cartledge

Baxter Dury White Rock Theatre, Hastings 21 February 2020

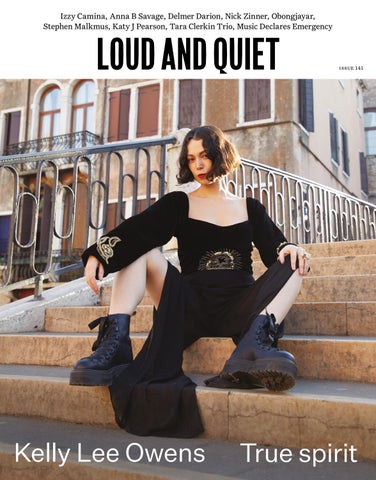

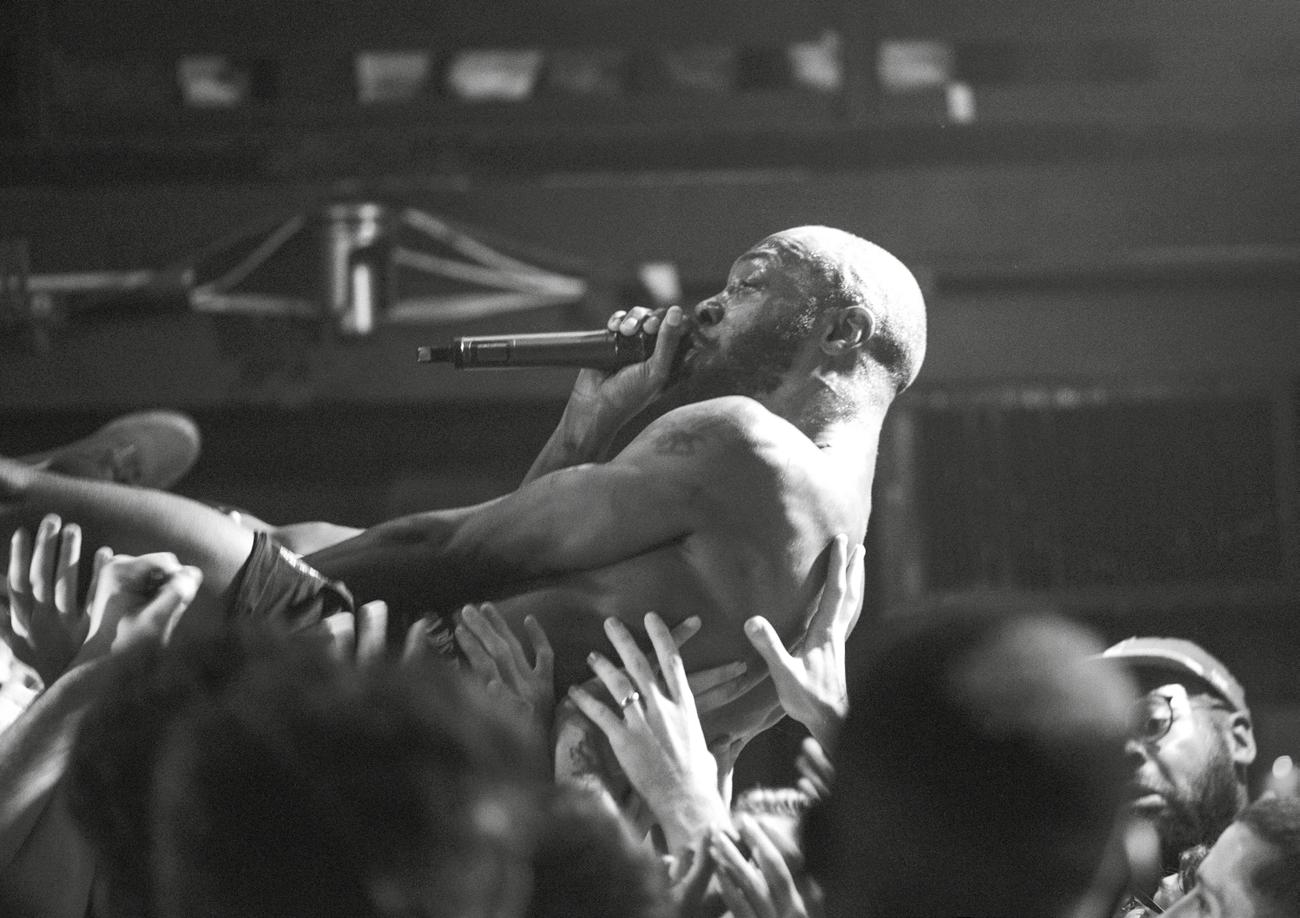

JPEGMAFIA Earth, London 27 February 2020

“I came here to do some nasty shit,” cautions Barrington Hendricks, hastily unzipping his orange hi-vis jacket. Though appearing twenty minutes late, he wastes little time to reassure us that no one’s getting short-changed this evening. It’s a genuine disclaimer, and judging by the ensuing frenzy, it’s not one anyone’s about to take lightly. Tonight will be the first of two sold out London shows one week apart for Baltimore’s JPEGMAFIA, and it’s shaping up to be a defining, no-holds-barred assault.

Eyeing up the onlookers, he stalks the stage perimeter. No one is truly safe – journalists, politicians, celebrities, misogynists, feminists, rock ‘n’ roll heroes, the alt-right, overly sensitive white people and even Peggy himself all stand defenceless and exposed. The polished keys and course bassline on opening the track ‘Jesus Forgive Me, I Am A Thot’ is momentarily stifled by chants of “fuck you, Peggy”. It all feels dangerous and strangely masochistic, and Peggy feeds off this deprecative ovation.

Much like on his previous two records, on stage JPEGMAFIA is erratic

and unpredictable. A rasping, ablebodied vocalist, he spits from the guttural depths of his throat, each round cocked and ceaselessly reloaded. Geiger-counter style atmospherics on ‘Thug Tears’ scrape the air, all the while Peggy writhing through each delirious verse. He briefly detaches himself from his own apocalyptic production, sometimes fluctuating between naked a capella and his music’s hellish reality, all of which are illustrated through bars of brilliant, darkhumoured absurdity.

On his latest album, All My Heroes Are Cornballs, Peggy explores his feminine side, and as he returns to the stage following a blown-out rendition of ‘Thot Tactics’, this is played out. “Your make-up is incredible!” he compliments an audience member.

Igniting anarchy with abrasive Veteran favourite ‘Baby I’m Bleeding’, he eventually surrenders his tired limbs to ‘Free To Frail’. A melody-driven introspection of his own fame and achievement, it’s the first time he looks truly vulnerable.

Spoken with uncensored conviction, he says, “this last song is dedicated to my least favourite musician”. The appropriately-titled finale, ‘I Cannot F*****g Wait Til Morrissey Dies’ feels enough to blast Moz into utter oblivion. Ollie Rankine Full of down-at-heel artists, down-trodden bohemians and down-from-London bearded types, the population of Hastings can be identified in many a Baxter Dury lyric, so there couldn’t be a more fitting place for him to begin his tour for new album The Night Chancers. Tonight, we’re in the White Rock Theatre as the aforementioned rag tag descend on a venue more accustomed to panto than pop satirists. Pints are downed in front of Jason Donovan posters as the wind crashes in from the coast just outside, the atmosphere an intoxicating mix of jollity and impending chaos.

These are Baxter’s people and a warm reception awaits his entrance as he eases into an all-encompassing, careerbest set. The watching crowd might not know ‘I’m Not Your Dog’ and ‘Slumlord’ from the imminent release but the songs are met with gleeful faces – it’s hard not to love Baxter’s wonderfully eccentric presence. While the fresh material continues to plough similar ground to previous works there’s a certain edge to tracks like ‘Carla’s Got a Boyfriend’, perhaps brought on by the cold reality of romantic failure that lifts their onstage delivery.

Dury is clearly relishing playing these songs to an audience for a first time, but much of the onlookers’ pleasure comes with old favourites. It’s not until a mid-set rendition of ‘Oi’ that we see some real movement in the crowd, and when ‘Miami’ arrives later on there’s welcome electricity in the theatre. Much of the fun in Dury’s music lies in his clever wordplay and character sketches, and on first listen The Night Chancers delivers this in droves. The title track digs deep into seedy 4am territories, and ‘Sleep People’ depicts the kinds of vagrants with which the Hastings crowd would be all too familiar. Despite the darkness, there’s vivid humour in these sordid tales.

The performance is littered with a few unwelcome sound problems which

seem frankly irrelevant to both Dury and his fans, both old and new. Shoulders are shrugged and jokes are shared. “What’s the matter,” he screams, “sea salt in your ears?”. As the band launch into an encore of ‘Cocaine Man’, ‘Prince of Tears’ and epic new album finale ‘Say Nothing’, there’s a typically vicious takedown between songs. “Fuck being polished,” spits Dury. It’s a sentiment that Hastings seems to share. Ian Roebuck

Sleater-Kinney Manchester Academy, Manchester 27 February 2020

The fact that one member of SleaterKinney is playing something close to a hometown show here in Manchester is instructive: they aren’t the band they used to be. Katie Harkin’s mum and dad have crossed the Pennines from Leeds to be here tonight to see their daughter make up part of what is now a five-piece iteration of a group formed twenty-five years ago, four and a half thousand miles away. Not present at an Academy that is a little under three-quarters full is Janet Weiss – not in person, anyway. Figuratively speaking, her presence – or lack thereof – is impossible to ignore. Last August’s veer off into dark electro territory with the St. Vincentproduced The Center Won’t Hold cost Carrie Brownstein and Corin Tucker their drummer. The timing couldn’t have been worse, coming after the album had been announced but before the extensive tour in support of it got underway. What the departure has done is allowed Brownstein in particular the opportunity to recraft this new iteration of the band – featuring St. Vincent sidewoman Toko Yasuda on keys – in her own image. The show is a far more stylised affair than the No Cities to Love tour was five years ago, particularly on the new tracks, none of which sound much less hollow than on record.

They also feel out of place next to what is otherwise a veritable hit parade of older material; the sterile synthpop of ‘Hurry on Home’ and ‘RUINS’ kills the pace of the rock and roll groove of old. The fizzing hat-trick of ‘Bury Our Friends’, ‘One More Hour’ and ‘Ironclad’ has the sting taken out of it by the selection of a new cut, creating a weird atmospheric disconnect between band and crowd.

This is a band that has undergone serious stylistic divergence before – sometimes on the same album – it’s just that this one seems to be proving a more awkward transition than before. It just doesn’t feel much like Sleater-Kinney at the minute. Hopefully, on the other side of it all, it will again. Joe Goggins

A Winged Victory For The Sullen Bruges Royal City Theatre, Belgium 25 February 2020

A Winged Victory for the Sullen’s (AWVFTS) recent album, The Undivided Five, saw Dustin O’Halloran and Adam Wiltzie’s ambient neo-classical outfit attempt to navigate the spiritual bookends of existence, trying to unfurl the chain of events that saw both the sudden death of close-friend and fellow composer Jóhann Jóhannsson and the birth of O’Halloran’s first child.

The 19th-century Bruges Royal City Theatre feels custom-built for their searching sound, its high-domed roof a perfect conduit for these undulating compositions. The sparse but effective lighting and smoke effects meld majestically with the opulent gold and Rubens red that adorn the baroque auditorium.

The duo begin with the sombre piano strokes of ‘Our Lord Debussy’, summoning an atmosphere that grows in intensity over the next hour. During the set, there is no silence, only bridged gaps of tension that reverberate around the theatre as O’Halloran and Wiltzie operate frantically on either side of the cramped stage, with the strings and brass of the Brussels-based Echo Collective oscillating in-between.

Minutes tick by with AWVFTS exploring threadbare arrangements; valuable pauses for breath before they invariably grow to a unified cacophony, strings battling one another and piano keys stabbing the brittle electronic veneer to conjure a potent aural life-force. These crescendos are spaced expertly, each visitation absorbing the theatre deeper into its celestial abyss without resistance.

By the end, everybody on stage looks exhausted, stumbling through an encore like shell-shocked ballerinas, but O’Halloran and Wiltzie radiate a defiant jubilance, having re-connected sonically with a meaninful period in their lives. It’s an outpouring of cosmic bereavement and bewilderment, and a revelation to witness. Robert Davidson

The Perfect Candidate (dir. haifaa Al mansour) At the start of the month of his life, during his acceptance speech at the Golden Globes, Bong Joon Ho said, “Once you overcome the one-inch tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.” It’s a bit of a ham-fisted intro here, as The Perfect Candidate is neither a South Korean production, nor as extraordinary as Parasite. But what is? Still, I couldn’t help but think of that when watching Haifaa Al Mansour’s latest film, and how Bong Joon Ho might have said “many more amazing worlds”. He’s right about the subtitles, of course – they remain an obstacle for even the most avid MUBI subscriber, who scrolls back and forth fishing via language first and foremost: “Oh yeah, I love world cinema, but how am I meant to work into the night if I have to always be looking at the movie I’m watching?!”

The Perfect Candidate is an introduction to an amazing world and a pretty good film – a great film, if you like things low key, which is a speciality of director Haifaa Al-Mansour’s. As the first Saudi woman to direct a feature film, her 2012 debut, Wadjda, was about an 11-year-old girl who defied her parents to buy a bicycle so she could race against boys. It was a movie that kept things beautifully simple as it zeroed in on the gender culture of her country – something that The Perfect Candidate does once again, subtly celebrating the music and local landscape of Saudi Arabia as it goes. Al-Mansour’s real life strength as a Saudi woman is reflected in the story’s protagonist Maryam, a doctor in a quiet corner of Riyadh who’s constantly having to earn the respect of her male colleagues and patients, despite her abilities. When a misunderstanding leads to her becoming the first woman to run for local office she leans into her election campaign, to better the hospital she works in (her prime/only policy is to resurface the road to the emergency room), but also to prove her worth to most of the older men in the town, including her father – a self-centred musician who hits the road with his band as he mourns the death of his singer wife.

Needless to say, the backbone of the movie is its story of female empowerment and societal progress, with Maryam an easy hero to follow, supported by her two sisters. Maryam is the film – in message and dignity. Al-Mansour makes sure to not throw all the men under the bus though – something that many in the West can do somewhat conveniently in an age of increasing Islamophobia. There’s plenty of sexism to go around here, but Maryam’s father cuts a sympathetic, lost figure, whose selfish rather than oppressive. The younger character of Omar, meanwhile, represents a more modern change in attitudes towards women, while his elderly grandfather’s redemption moment in the film’s final scene is the movie’s emotional gut punch, and Maryam’s true victory. Stuart Stubbs

Doomed to Fail: The Incredibly Loud History of Doom, Sludge and PostMetal— J. J. Anselmi (rare bird) Rock and roll has always loved talking about itself. For a genre that hasn’t been around for a century, there’s a deluge of memoirs, oral histories, and so on, many professing to be “definitive” and all hoping to become the next Please Kill Me. Pick a genre, an artist, or a year, and someone will have written 300 pages to tell you why it’s a cornerstone of modern music.

Now doom metal has found its noble chronicler in J.J. Anselmi, a writer, sludge musician, and, most importantly, an avid fan of heavy music. His new book Doomed to Fail is a broad window into the worlds of doom, sludge, and post-metal, with each chapter dedicated to a different band and its contributions to its genre. His approach lacks the intimacy of a memoir and the quirks of an oral history, but as a general overview, the book is a comprehensive account of the heaviest music of the past 50 years.

Starting with the influential distortion of guitarist Goree Carter’s 1949 track ‘Rock Awhile’ and finishing with Chelsea Wolfe’s experimental doom folk, Doomed to Fail can sometimes feel like a collection of pitches: “These bands are great, here’s why.” Anselmi is at his best when he lets his enthusiasm run away with himself and his prose drifts into the phantasmagoric melodrama characteristic of doom metal. Of the stoner metal legend Sleep, for example, he writes, “Somewhere beneath an ocean of sand rests a wraithlike creature made mostly of sentient weed smoke. It wears a thick, velvet shroud.” In moments like these, Anselmi shows how doom, for all its weight and darkness, can be incredibly fun. But the format of Doomed to Fail requires Anselmi to move quickly, and as a result he sometimes moves on when you wish he would linger. The violent tension between the D.C. hardcore and metal scenes in the ’80s, for example, gets only a passing mention, along with the fraught relationship between Earth’s Dylan Carlson and Kurt Cobain (Carlson procured the gun that Cobain used to kill himself).

In all fairness to Anselmi, however, his book isn’t really interested in unpacking the more fraught and complicated corners of the shared history of sludge, doom, and post-metal. This, in fact, is its greatest strength. Where so many books aim to offer a breaking insider take or an essential narrative, Doomed To Fail is simply a document of the music its author loves. “Before I get into the history of this music,” he writes, “I just want you to know that you can be doomed, too.” And he makes a passionate case for why this slow, ominous music has crawled out of the crypt into so many people’s hearts. As a historical document, that may be more valuable than any fresh tell-all or critical take. Colin Groundwater