6 minute read

D[I]ASPORA

D[i]aspo ra

Understanding my ethnic narrative

Advertisement

I am a 竹昇 (pronounced jooksing), a Cantonese term which is used to describe a Chinese person who was born in a country with a dominant Western culture. The first character, jook, means bamboo and is used for this term because the compartments in a bamboo stalk prevent water flowing from one end to the other. Like bamboo, there is no single culture that flows through jook-sings. They do not belong to either Western or Chinese cultures. Although I was raised in a Cantonese-speaking household, my parents reminded me: “You are born in Canada, so you are Canadian.”

by Tabitha Mui

Tabitha is an Uptick Baptist Women alumni and a recent MDiv graduate of Tyndale University and Seminary.

Being a member of a diaspora community is complex. Membership is often rooted in a sense of loss, regardless of whether the decision to leave was voluntary or not. Identifying with this membership, however, becomes problematic when applied to Chinese people who were not born in China: how am I an overseas Chinese person, when the term “overseas Chinese” for me is someone who was born in China? Diaspora implies that I acknowledge a country different from the one I currently live in to be my home. But Canada is my home.

Tabitha Mui Does that make me less Chinese than a Chinese person from China?

As I observe other second-generation Chinese Canadians, I notice that we fall within a spectrum of either being fully assimilated with Western culture or figuring out how to negotiate a space to belong with other Chinese Canadians. These complexities remained mainly at the stage of navel-gazing until COVID-19 hit and George Floyd was murdered.

“Go back to China!” Recent articles and interviews have documented how Chinese people and other Asians experienced racist attacks in response to China’s role in the spread of COVID-19. AntiAsian actions are not unfamiliar in Canada’s history: the Chinese Exclusion Act that passed on July 1, 1923 is remembered by many Chinese Canadians as Humiliation Day. Deep inside, I wanted to believe that these attacks were isolated incidents. I was both ashamed and afraid–ashamed of being affiliated with a country that holds a very different worldview than my

My repentance and activism must go hand-in-hand.

own and afraid that my loved ones and I might be the next targets.

I suddenly realized how fragile racial privilege is and how it provides an illusion of safety and security. My silence to racial oppression could no longer keep me and my loved ones safe. It was at this point that I paused, realizing that my newfound sensitization to systemic oppression came out of selfishness. My communal mindset had only extended to the wellbeing of those within the borders of my ethnicity: “Let us look after ourselves, and let others take care of themselves.”

A contributor to this mindset, I believe, is the proximity to power and privilege that has been given to Chinese Canadians (thanks to the model minority myth), of which I am a benefactor. The model minority myth is one in which those in power (i.e. White people) will use the successes of certain minority groups to disclaim unfair treatment against other minority groups. For example, if a Black person highlights the lack of opportunities for advancement in an organization for those who are non-White, the White person will point to the number of Asians who hold managerial roles to prove that diversity and inclusion are values that are upheld by management. Therefore Asians who are successful within the system are held as the model minority for other minority groups and, as a result, enjoy a certain degree of privilege and power that would otherwise be non-existent.

As a Chinese person who has benefited from this myth, I must face the complexities of my role as an oppressor. I can only stand in true solidarity with fellow Black, Indigenous, and Persons of Colour, when I acknowledge and repent how I have been compliant within this racial hierarchy and begin to actively resist the temptations (i.e. power and privilege) that this role offers. In short, my repentance and activism must go hand-in-hand.

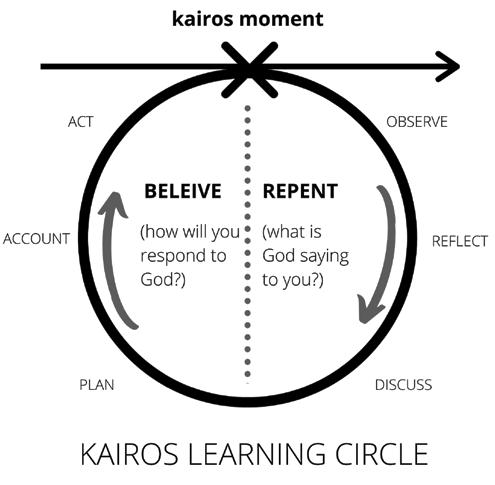

As I reflect on all that God has revealed to me during this season, one thing is clear: there is nowhere to “go back” to. This is home and I need to embrace being both Chinese and Canadian. But there is more. God has shown me the complexities of my cultural identity as it interplays with other cultures and He is now inviting me to observe how interactions that exist within certain systems and structures do not reflect the values of His kingdom: “You have come so far, My daughter, and I have shown you My heart. Will you allow Me to form you for My kingdom, trusting that I made you a secondgeneration Chinese Canadian for a purpose?”

CH OSEN | HOLY | CALL

Rev. Della D. Bost ED

Tell us about how you experienced God’s call to be ordained. The first time I remember a calling on my life was when I had just become the Sunday School president of the Amherstburg Regular Missionary Baptist Association (ARMBA). During a youth program at our annual session the Holy Spirit moved. The Lord told me: “Feed my lambs.” After a seven-year term as president, I felt the Lord leading me to a deeper level of teaching His Word. Being an evangelist for our

Rev. Bost has twice served First Regular Baptist Church in Dresden, Ontario as interim pastor. She pastored at First Baptist Church Puce for nine years and for just over a year, she’s pastored First Baptist Church Windsor. Association gave me opportunity for more speaking engagements and experience in the pulpit.

During a funeral service for a church member, when I was in the pulpit assisting my pastor, I distinctly heard God’s voice. “Preach my Word,” He directed me. Twice.

What was your process of responding to that call? Ever since I can remember, I was taught that women did not pastor. At first, I was afraid to tell anyone, so it was a long, hard process for me. I had to decide within myself to answer God’s call. It wasn’t until I retired that I took courses at McMaster University and Toronto Baptist Seminary to complete my course requirements for ordination in the Canadian Baptist family. Being ordained by my association and my home church, First Baptist Church Puce, was one of the most exciting times in my ministry.

How has the Spirit kneaded holiness into your ministry? Holiness was kneaded into my ministry by the lifelong example of my father who taught me to walk upright, to love God and always reflect Christ’s image. Holiness is more than acting, thinking and being holy. It is having that deep personal daily relationship with Christ.

What has challenged you most about declaring God’s goodness? My greatest challenge is teaching and preaching without my family responding to God’s goodness, grace, mercy and forgiveness. It is difficult to watch when people walk away without putting their faith and trust in God. But as Paul taught in 1 Corinthians 3:6, some plant and others water, knowing that God gives the increase.

What would you want a young Baptist woman seeking ordination to know? Ministry is challenging and ambitious. There are many situations that require your utmost readiness. Have unshakable faith and put a “But God . . . ” in your spirit. Joshua 1:7, 9 are verses God gave me when I began my ministry and ones I hang onto even to this day. I feel deep joy in sharing them with you.

Remember, you are a child of the Most High God. You are who God says you are: strong, loved, forgiven, created with purpose, victorious, powerful, and fearfully and wonderfully made. Go ahead . . . my sista’ . . . preach the Word!