9 minute read

Priced out of the River Cities? market sets it all’

PRESIDENT & CEO Lacy Starling

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER Mark Collier

MANAGING EDITOR Meghan Goth

PRINT EDITOR Kaitlin Gebby

SPORTS EDITOR Evan Dennison

The LINK nky Kenton Reader is a weekly newspaper. Application to Mail at Periodicals Postage Prices is Pending, permit number 32 in Covington, Kentucky. The LINK nky Kenton Reader office of publications and the Periodical Pending Postage Paid at 700 Scott St., Covington, KY 41011.

For mailing address or change-of-address orders:

POSTMASTER: send address changes to The LINK nky Kenton Reader: 31 Innovation Alley, Covington, KY 41011 859-878-1669 | www.LINKnky.com

HAVE A TIP? News@LINKnky.com

WANT TO ADVERTISE? Marketing@LINKnky.com

WANT TO SUBSCRIBE?

Send a check for $31.80 ($25 trial rate plus 6% Kentucky sales tax) to our principle office or scan this QR code below

No part of this publication may be used without permission of the publisher. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings, and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, please let us know and accept our sincere apologies in advance.

At the end of Greenup Street in Covington, just as the road bends around the city of Covington sign welcoming northern visitors and residents alike, sit two buildings.

One is an apartment complex with 25 units spread across four floors.

The other is a building that formerly housed Lil’s Bagels, a specialty restaurant that was popular among local residents.

This small stretch of road has become a microcosm of a trend that’s swept up many in the urban areas of the region, both individual residents and businesses. As cities and economic institutions have made changes to draw in new development, demand for housing and commercial space has driven up property values and rent prices, making it harder for established residents and businesses to keep pace. In the worst cases, these conditions can lead to residential displacement and the closure of businesses, both of which have occurred on Greenup Street in the past year.

Lil’s Bagels shuttered in January, following attempts to negotiate new lease terms with its property manager, Gravity Management Group. The shop had been a fixture of the community for years. Many in the city – including Covington Mayor Joe Meyer, who wrote a letter to Gravity Management officials entreating them for an amicable negotiation with Lil’s owner, Julia Keister – felt a profound sense of loss when the shop closed after Keister and Gravity failed to reach a lease agreement the business could afford.

BY NATHAN GRANGER | LINK nky REPORTER

company Urban Sites.

The Hayden is a 110-plus unit, $31.4 million project designed to bring young professionals and their families to the Riverside District of Covington, according to the development’s website. With monthly rents ranging from $1,225 for a 550-squarefoot studio to $2,600 for a two-bedroom, two-bathroom unit with double the space, one Woodford resident said he knew what the opening of The Hayden signaled: Rents were surely about to go up.

But why would the opening of a new building, albeit one that was more expensive, affect rent prices in The Woodford?

The answer lies in a set of overlapping historical and market conditions that have contributed to the rise of both rental prices and property values throughout the region and, indeed, much of the country.

To begin with, governments, civic organizations and private firms have been making conscious efforts to increase economic development, attract employers and draw new residents throughout the region since at least the 1980s, when coordinated redevelopment of commercial property along the riverfront took place.

“We want well-planned growth,” said Northern Kentucky Chamber of Commerce President and CEO Brent Cooper. “We want a vibrant community.”

This cross-institutional model is “a perfect example of how government, public, private folks can get together, champion something that then can lead to hopefully more investment in our community,” Cooper said. “That’s a lot of jobs, a lot of people living in our community, visiting our restaurants.”

The rationale for the kind of planned growth for which Cooper advocates goes like this: Get multiple sectors of society – government, local residents, businesses and other stakeholders – on the same page. Invest in a project that’s purported to be mutually beneficial to all parties, an investment that usually involves funding from both public and private interests. Then offer job opportunities that accompany the development to local workers, who will invest their wages and taxes back into the community.

Development, however, is often a double-edged sword, said Shannon Ratterman, interim executive director for the Center for Great Neighborhoods, a Covington nonprofit. The center owns several residential and commercial properties and has contributed to the ongoing development of the city.

“That kind of automatically creates a higher demand,” Ratterman said. “Which, of course, … that’s how the market works is that it increases the rents and what it costs to own a property.” on the cover Madison Avenue in Covington in the 1950s and today. Historic photo provided | Kenton County Public Library. Current photo by James Robertson | LINK nky contributor.

The occupants of the residential property, called The Woodford, faced a similar situation only a few months after Lil’s left.

In the early months of 2023, Woodford residents saw completion of construction on The Hayden, a luxury apartment complex built from the shell of the former Kenton County Administration Building, which housed the jail, on East Court Street next door. Both The Woodford and The Hayden are managed by property management

The NKY Chamber is one of several economic development groups that have collaborated with local and state governments to spur such regional development. When Cooper spoke with LINK nky, he gave an example that illustrated how this model of development works. The planned construction of a new complex health science lab in Covington, he said, sprang out of prolonged coordination between development organizations, such as the NKY Chamber and BE NKY (formerly Northern Kentucky Tri-ED), private medical firms and elected officials. The project eventually got an injection of $15 million in state money from Gov. Andy Beshear.

Ratterman’s perspective offers a glimpse into market forces that eventually subsumed Keister’s ability to negotiate effectively with Gravity Management, the same forces that found their way onto Woodford residents’ doorsteps.

In March, after construction on The Hayden concluded, Woodford tenants began receiving notices to vacate. Various upgrades were planned for the building, and in order for the company to execute them, the tenants could not live in their units.

One tenant, Matthew Craig, said he saw it coming.

Continued from page 3

Craig wears his politics on his sleeve, sometimes literally. He grew up in the region but returned to Covington in March 2022, after traveling across the country stumping for the presidential campaign of U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vermont.

Craig said he leased the apartment knowing there would be some moving pieces the closer he got to the end of his lease.

“When I moved here, they were clear that the whole premise was that the building was likely to be sold, and ownership was likely to change,” he said. “So, when I was looking at the building, it was cheap. It was cheaper than a lot of apartments in the area.”

Some tenants were given the minimum amount of time required by law to vacate, while others were able to extend their leases month-to-month, with the only constant being that they had to leave.

“Last year, there were a lot of residents that were very uncertain what’s going to happen,” Craig said. “But there was just a lot of confusion as to, ‘Why or how can this happen?’ There are neighbors here on a fixed income that cannot find somewhere else.”

Craig said he is OK financially and can afford a higher rent, but that doesn’t mean he’s pleased with the dissolution of the community he settled into at The Woodford.

“It’s going to be very different,” Craig said in March before he moved out. “It’s going to bring in an entirely different kind of vibe to Covington. A lot of people will complain that it’s kind of changing the face of this area and it’s disrupting.

“If we weren’t forced to leave, the community of residents would stay intact. There was a community that existed when I came in, that would have continued to exist, and there are tenants that need this community. We have folks that are on Medicaid and Social Security on a fixed rent. We look out for each other.”

The sort of planned growth for which Cooper advocates is but one kind of economic development that has taken place in the region and one of several factors that contribute to the phenomenon of people getting priced out.

Brian Miller, executive vice president of the Northern Kentucky Builders Association, explained how these factors play out in Northern Kentucky, citing three main causes: increases in materials costs, ex- penses to remain compliant with zoning restrictions and shortages of skilled labor. Several contractors who spoke with LINK nky corroborated the rise in materials costs.

“In Greater Cincinnati, when you raise the cost of a home by $1,000, you have priced out over 1,200 families from being able to buy that home,” Miller said.

“You cannot make more used homes, right?” he said. “So that means that you have a fixed supply, and when you move people out of the new market, it means you have more people in the used market. Supply and demand: You’ve got a fixed supply with a higher increase in demand, (and) costs go up.”

What’s more, the region’s population has been steadily increasing, which puts even more pressure on supply. As LINK nky pointed out in the May 12 edition of the LINK Reader, Campbell, Kenton and Boone counties’ populations increased by about 3%, 6% and 15%, respectively, between 2010 and 2020, according to data by the U.S. Census Bureau.

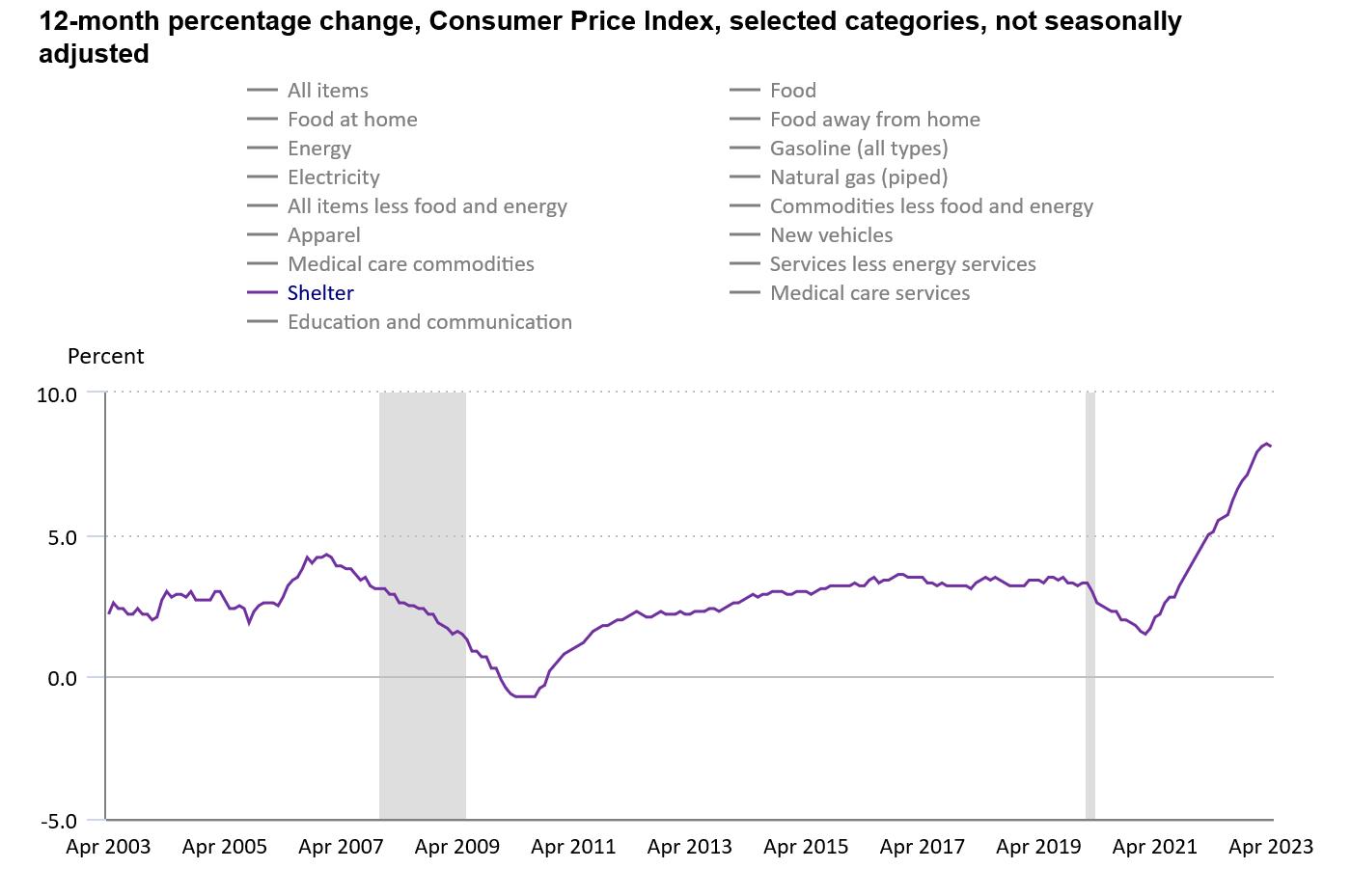

Finally, spiking U.S. inflation over the last year has amplified the pressure on the development market.

These forces overlap in such a way that they disincentivize the construction of property for low- and middle-income people and ratchet up the price of existing property.

Even when developers build new homes, they often have to market to demographics that will pay enough that the developers turn a profit.

“Lately, that has been the affluent,” Miller said.

Academic and government literature reviewed by LINK nky in the reporting of this story broadly corroborate Miller’s assessment.

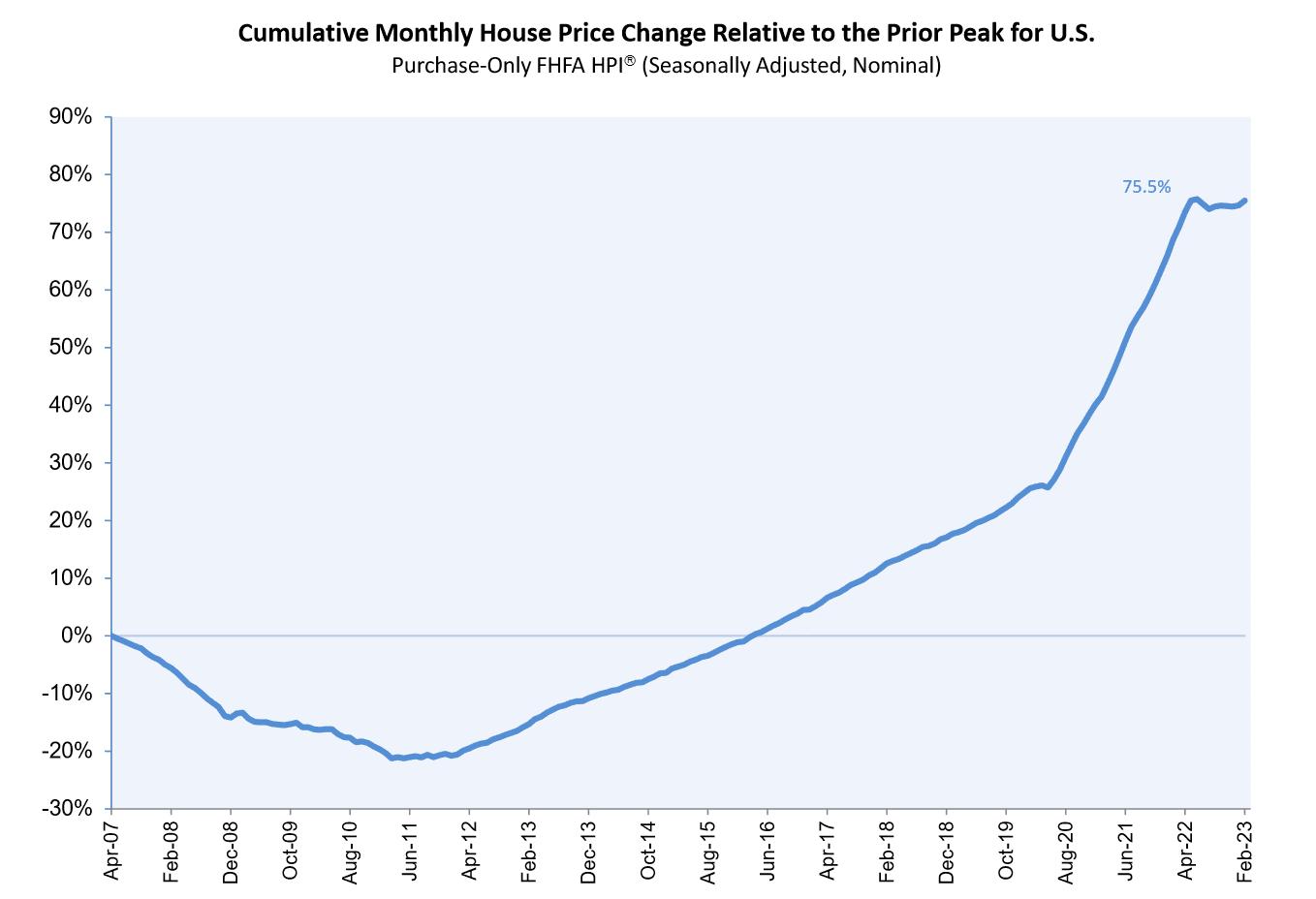

Economist Nathaniel Baum-Snow, professor of economic analysis and policy at the University of Toronto, explored the issue in a recent white paper published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives. He analyzed the effects of housing demand on different communities throughout the United States, noting that the “rate of new housing construction has been low or falling in all types of locations since 2000.”

A study from Fannie Mae in October 2022 suggested that housing supply throughout the country has failed to keep up with demand, although that study said the Greater Cincinnati region has tended to be more stable than other regions.

Michael Denigan, owner and operator of Florence-based Hillcrest Home Solutions, has been in the real estate business since the 1980s. From his vantage point operating a large real estate firm, he’s witnessed the region change over the years.

Denigan said the region has always been attractive to developers due to its low cost of living, low property tax rates and high general quality of life when compared with other regions. He added that the housing market in Northern Kentucky has tended to be stable when compared to other markets.

“Three or four years ago, we were selling bilevels for $160,000,” Denigan said. “Now they’re $250 or $240 (thousand). ... That caused the rents to all go up.”

An increase in economic activity attracts even more investment to the area, continuing the cycle. Yet, unlike with a plannedgrowth approach such as Cooper endorses, later arrivals to the local economy are often less deliberate in how they act.

“It used to be, the investors were all local,” said Sherri Walker, Hillcrest’s property manager, whom Denigan hired in 2011. “Well, because this market – it’s such a sweet spot around here with all the variety of industry in Cincinnati and everything –now we’ve got investors coming in from all over. You have hedge funds like American Homes 4 Rent and a couple of the other ones that are coming in and buying up all that property.

“They’ve bought about 6,000 homes in the Greater Cincinnati area.”

American Homes 4 Rent, which has changed its name to AMH, isn’t alone among hedge funds and private equity firms that have entered the regional market.

Brandon Holmes, Covington’s neighborhood services director, said Berkshire Ha- thaway and Blackstone also have a presence in the region, although he was unsure of the scale of their investment. Holmes is a former fellow with the Department of Housing and Urban Development and a self-proclaimed “housing geek.”

Hedge funds have drawn criticism from some due to their model of buying large numbers of single-family homes and either letting them remain vacant while equity increases, or converting them to rental properties.

At Hillcrest properties, Walker said, the median rent these days is between $1,500 and $1,600 per month. Its properties’ values, meanwhile, range from about $160,000 to $400,000.

“The market sets it all,” Denigan said.

Most of the sources LINK nky spoke with confirmed the challenges the region faced.

“I think all businesses and residents need to find ways to continuously adapt to new market forces and impacts on our community,” Cooper said. “A big issue for us right now, and it’s every community in the country right now, for sure, are issues of inflation. … I think we have two jobs for every one person right now in the country. That is an issue that we’re all going to have to deal with.”

To that end, a variety of programs, policies and organizations have been established in Northern Kentucky to aid in the development of small businesses and the increase in both affordable housing and the number of homeowners.

One such government program is the Northern Kentucky HOME Consortium, which uses federal grants to provide 0% homebuyer loans in the consortium’s member cities. It also invests in commu-

Continues on page 6