2 minute read

The High Ankle Sprain

by ERIC KOHN

Advertisement

The running back hits the open hole with a burst of speed. His left ankle is planted and he readies himself to perform another jump cut to get into the secondary when he is hit from the outside by a linebacker that is pursuing down the line. He feels immediate pain in the outside of his ankle and is unable to put full weight on it. He limps off the field and seeks out the training staff for assessment.

IF this athlete’s ankle is not correctly diagnosed and treated appropriately a long journey of chronic pain, instability and inability to return to high level performance will be in his future. There are 3 main types of ankle sprains, the high ankle, medial and most common lateral ankle sprain. What is a high ankle sprain? How does it happen and what steps can be taken to help the athlete return from the injury?

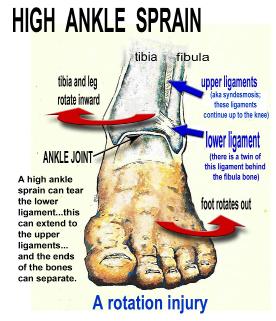

A high ankle sprain or syndesmosis injury, differs from a common lateral ankle sprain in many ways. The mechanism of injury with the common lateral ankle sprain is a “rolled down and in” movement of the foot and ankle and the pain is usually felt below the lateral ankle bone or malleolus. The opposite is true with a high ankle sprain with a mechanism of the foot rotating out. Another mechanism of injury occurs with a planted foot and the athlete falling forward. The pain is localized in the front or above the outside ankle bone (lateral malleolus).

The high ankle sprain occurs when the tibia and fibula are stressed and pushed apart. This can create stretching of the ligament that holds the bones together at the ankle (anterior distal tibiofibular ligament). The syndesmosis membrane between the two bones which helps to create stability can also be stressed apart.

This anatomy difference is one of the reasons the high ankle takes longer to recover from. Walking on a high ankle injury will limit healing due to more stress being placed on the injured ligament which creates more separation of the tibia and fibula.

The latest research shows that the frequency of high ankle sprains occurs one out of every 10 ankle injuries. The first step is to seek medical attention from your sports medicine provider on the field. They will quickly assess you and determine severity of injury. The use of x-ray radiographs is commonly performed to help rule out any fractures that may have occurred in the ankle bones and to determine if there is increased space between the tibia and fibula. If a high ankle sprain is diagnosed, begin by following the recommended treatment plan provided by your sports medicine provider. The use of crutches and a protective boot will provide initial immobilization and help to decrease pain. The use of RICE (rest, ice, compression and elevation) are to be followed to start the healing process. After 4-6 weeks the use of the boot is usually replaced with a more functional sports brace as you begin the rehabilitation process. It is imperative to immobilize initially and allow the ligament to heal before stressing it again.

At the 4-6 week mark your sports medicine provider will begin the process of returning strength, balance, and endurance back to your ankle and lower extremity. This process of gradually adding more stress to the ankle is done only without increased pain or swelling. If either occur, the process is slowed to allow adequate healing before progressing. Pain is the guide with returning back to activities. The rehab process must include many balance exercises. This is the key to avoiding chronic injury. The injured ankle has many receptors in the joint that become damaged and need to be addressed during recovery. Balance exercises from simple, one legged stance holds to more complex, single leg hopping will help get you on the path back to the field.

Early assessment, correct diagnosis, immobilization and gradual progression of stress to the healing ankle will lead to the successful return to sports after a high ankle sprain.

Eric is a Board Certified Orthopedic Clinical Specialist, Doctor of Physical Therapy and Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist. He practices at St Cloud Orthopedics in Central Minnesota and is an adjunct professor at The College of St. Benedict/St John’s University.