4 minute read

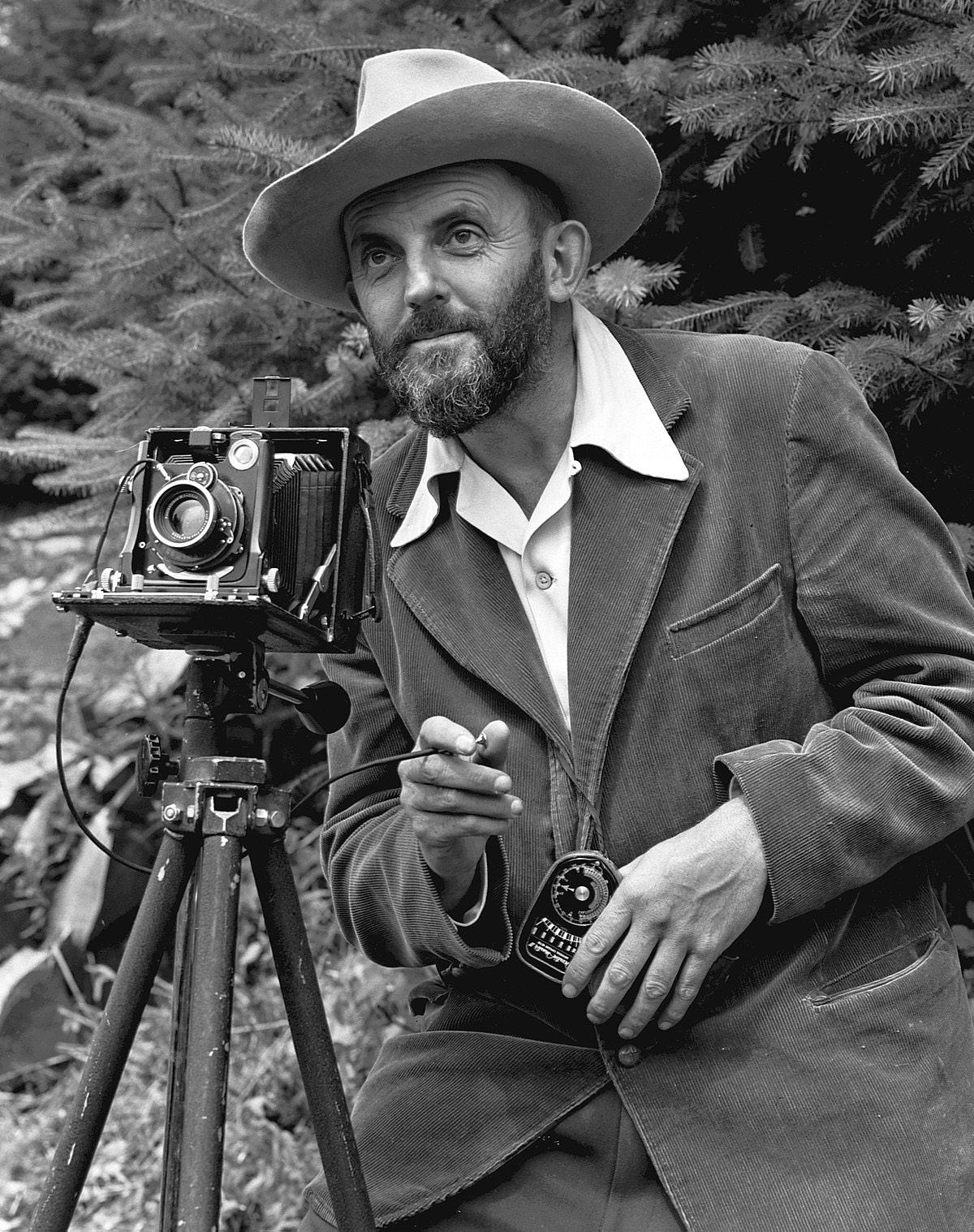

Ansel Adams

“Landscape photography is the supreme test of the photographer – and often the supreme disappointment.”

Ansel Adams. 1902 - 1984.

Advertisement

21

Ansel Adams.

If you make a list of the most popular landscape photographers throughout history, it would not be a surprise to see Ansel Adams name at the very top. He can be considered “…the most important landscape photographer of the 20th century” (Britannica 2020).

Though he left school at 12, he went on to become a gifted pianist, and prolific author, publishing several photographic books and collections of photographs. In his autobiography, he talks of receiving a copy of ‘In the Heart of the Sierras’, by J. M. Hutchens, from his Aunt Mary; captivated by the illustrations of Yosemite and the stories of the cowboys and Indians, he convinced his family, who were at the time considering a family holiday, that this was the place to go. There at the age of 14, his father gave him his first camera, a Kodak Box Brownie. He recalls taking a photograph as he fell out of a tree, clicking the shutter as he fell. The image was upside down compared to the rest of the negatives on the film, much to the consternation of the man who developed it for him. Entitled ‘Half Dome and Clouds’, taken in 1916, in his autobiography, he says it is,

Half Dome and Clouds, (Upside-down Photograph). 1916. “one of my favourites from my first year of photography”. Ansel Adams Autobiography.

22

His passion for Yosemite flourished after this first visit. He ponders:

How different my life would have been if it were not for those early hikes in the Sierra – if I had not experienced that memorable first trip to Yosemite – if I had not been raised by the ocean – if, if, if! Everything I have done or felt has been in some way influenced by the impact of the Natural Scene…. These qualities to which I still deeply respond were distilled into my pictures over the decades. I knew

my destiny when I first experienced Yosemite. Ansel Adams, Autobiography.

A meeting with photographer Paul Strand in New Mexico in 1930 gave Adams a new direction to his photography. He saw in Strands images a

“…rich and luminous tonality, a style in contrast to the soft-focus Pictorialism still in vogue among many contemporary photographers”. (Szarkowski, J. 2020).

This divergence from Pictorialism led Adams to form in 1932 with 10 other photographers, notably Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham the F/64 Group, named after the smallest aperture, found on a large format camera., The

23

groups aim was to record the world around them without manipulating the photograph. Though short-lived this group has had a profound influence on photographers ever since, with several of its members becoming influential photographers in their own right. While the ethos of this group was to produce pictures without manipulation, to photograph the real, Adams used various filters on his camera, notably red, which dramatically changed the image, increasing the contrast between sky and ground, combined with his innovative darkroom methods during printing, he was able to produce dramatic images bordering on the surreal. Photographs with an immense depth of field and daylight skies that are almost black.

His passion for Yosemite and the Sierras is without question, it is evident in his pictures, and writings, where he is very protective of the place. Mark Klett who travelled and photographed in Yosemite says,

“What we saw in the Adams photographs is: ‘This is nature. And it’s beautiful because you’re not there”.

Terri Loewenthal. Psychscape 87. 2018. Jackson Fine Art Terri Loewenthal. Psychscape 602. 2018. CULT Aimee Frieberg Exhibitions Ansel Adams.

El Capitan, Yosemite

National Park. 1952. Robert Klein Gallery. Ansel Adams.

Nevada Falls, Rainbow.

1946. Atlas Gallery.

24

Alluding to the fact that few if any of Adams landscapes include people. Adams photographs of the American wilderness were the accepted view for many years, strong compositions of mountains and trees watched over by a brooding sky in almost a masculine way. Jacqui Palumbo’s article in Artsy.net equates this masculine perception to Adams photographs, comparing them to the romanticised view of the American West. This notion that gender can be attributed to the way a photographer interprets a photograph was explored in an exhibition in 1999 in Atlanta. The photographs of Terri Loewenthal were shown alongside those of Ansel Adams, examining whether gender had an influence on the way the photographer visualised the landscape. Not in the ‘Male Gaze’ way as theorised by Laura Mulvey, but as a comparison between men and women’s view of landscapes. When viewed side by side the images cannot be more different. Apart from the colour, Loewenthal’s images have more in common with those of pictorialism than that of Adams, a far more stylised interpretation of the same mountains. Adams’ photographs while majestic and impressive are not welcoming, they seem to say look from a distance but do not come too close, whereas Loewenthal’s pictures create a more inviting environment that encourages people to come and see how beautiful this place is. This warmth may be due to the fact that she uses colour whereas he was initially restricted to black and white. As Jacqui Palumbo says in her article, would Adams have visualized his photographs the same if he had been born a century later? The awesome brooding nature of Ansel Adams’ landscapes fits in with the theory of the sublime, which seems a more fitting analogy that that of the male gaze.

25

26