10 minute read

FUTURE STUDIES

Luca Locatelli

FUTURE STUDIES

Advertisement

It would be hard to find a more timely subject for the winning series of the LOBA 2020. The photographer takes part in the debate about the relationship between humanity, nature and technology, visualising the possibilities that could mean survival in the future.

Workers have been taking apart this Soviet-era nuclear power plant, near Greifswald in eastern Germany, since 1995, cleaning radioactive surfaces with steel grit so the metal can be recycled. Germany plans to shut down all its reactors by 2022; 10 March 2015 Previous page: The Greifswald nuclear power station was the largest in East Germany before it was shut down shortly after German reunification. The plants were of the VVER-440/V-230 type, which was the second generation of Sovietdesigned plants. In late 1989, the nuclear regulatory bodies of countries operating VVER plants found the need to fit many with new safety systems, which were discovered to be necessary in almost all areas. All East German reactors were closed soon after reunification, with restarting conditional on compliance with the stricter West German safety standards. Convinced that upgrading to the new safety standards was not economically feasible, the new unified German government decided in early 1991 to decommission the four active units, close unit 5, which was under testing at the time, and halt construction of the rest of the units; 9 March 2015

The nuclear reactor at Kalkar was finished just before the 1986 explosion at Chernobyl, Ukraine –and never used. It is now an amusement park with a ride in what would have been the cooling tower; 24 May 2015

Renewable energies are booming, but Germany’s use of lignite, the dirtiest coal, has not declined. At Vattenfall’s Welzow-Süd mine, some of the world’s largest machines claw 22 million tons a year from a nearly 14 metres thick seam. How long will that go on? “Very long, I hope,” said Jan Domann, a young engineer. “We have enough lignite”; 16 March 2015

An aerial view of the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group in TucsonArizona, USA. This is the largest aircraft storage and preservation facility in the world and handles nearly 3,300 aircraft. The arid climate of the region prevents corrosion and weather damage. The process to optimize the life cycle of such resource-intensive machines is a leading example of circular economy in the heavy industry sector. The so-called Boneyard re-manufacturing and repurposing technology makes the most out of planes that sit at the airfield. Precious parts are dismantled and reused, and entire aircraft can be reassembled and put back into service. At the end of the life cycle, they can be scrapped for steel and aluminium recycling; 29 October 2019

Professor Ruth checks the harvesting quality at the algae bioreactor at the Wageningen University Algae Park in the Netherlands. The university is working on a fifteen year roadmap project (2010–2025), that aims to develop a commercial and sustainable production chain for food, feed, chemicals, materials and fuels from micro-algae; 20 February 2017

Flying over the Westland in the Netherlands, the most advanced area in the world for agro farming technology. Furrows of artificial light lend an otherworldly aura to the greenhouses. Climate-controlled farms such as these grow crops around the clockand in every kind of weather; 3 March 2017

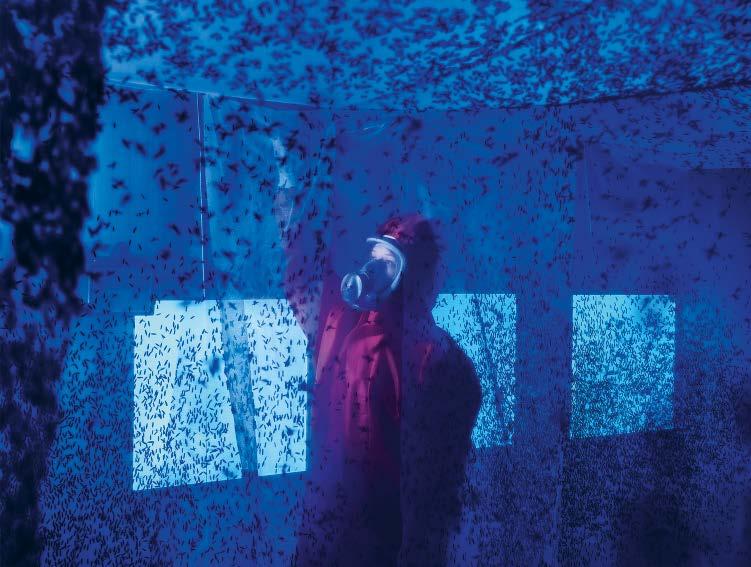

A portrait of Stephanie in an experimental net chamber room for insect farming at Entocycle, a start-up company in London, UK. To incite insects to lay eggs, rotten material is scattered around the floor, making it difficult to breathe without a gas mask. Here different spectra of lights are tested to measure their effect on flies and their reproduction. Entocycle is a young British company developing technology to farm insects on a large scale for industrial protein production. Representing a more sustainable and less polluting alternative to meat, these flies are fed in their larval state using organic waste coming from coffee and beer production. ”The farmers of tomorrow are the engineers of today” is Entocycle’s motto. It expresses the belief in the scaleability of their technology and its potential to change the protein market and reduce the amount of food waste in landfills; 10 October 2019

Inside this jungle of tomato plants illuminated by LED lighting, Henk Kalkman, a leading world authority for growers, inspects the plants. This picture is taken at Delphy, a research and development centre in the Netherlands, where academia and the private sector join together for experimental research. What could the future of sustainable farming look like? How is the world going to front the hunger crisis in the next decades? These questions took Lucatelli to the Netherlands on an assignment for National Geographic (@natgeo), to document this small country that has become an agricultural giant, proposing the most advanced high tech agro farming solutions to grow more with less; 17 October 2016

Wind energy is a fundamental aspect of the energy turnaround. For his documentation on the renewable energy sources of the future, Locatelli visited wind farms and also photographed in a factory in Denmark where wind turbines are manufactured; 13 March 2015

The great indoors provides optimal growing conditions for lettuce and other leafy greens at Siberia B.V. in Maasbree, Netherlands. Each acre in the greenhouse yields as much lettuce as 10 outdoor acres, and cuts the need for chemicals by 97 percent; 1 March 2017

Clouds rising from geothermal wells in Hellisheidi Power Station in Iceland. Iceland obtains approximately 87 percent of the energy for hot water in households and urban street lighting from geothermal sources. At 303 megawatts of energy and more than 100 wells, Hellisheidi is Iceland’s largest geothermal power station and the third largest in the world. It has been designed with a strong attention to the environment — green painted pipes minimise the visual impact on the landscape. A circular water system has been put into work to extract and pump back water underground. Energy production is the main cause of the climate crisis; therefore, finding a way to produce cleaner energy around the globe is one of the main challenges for the future. Geothermal is one of the most circular ways to produce energy while respecting the environment. It might be applicable in many countries that could rely on volcanic activity instead of burning coal or oil; 6 August 2019

Two automated grab cranes inside the Amager Bakke wasteto-energy plant’s collection chamber in Copenhagen, Denmark. Here, trash is dumped directly into the massive silo, which has a total height of 36 meters and can hold approximately 22 000 tonnes of waste. As it burns through trash at a rate of 70 tonnes per hour, Copenhagen has to import rubbish from Britain and Germany to make up for the Dane’s efficient recycling scheme, which leaves little landfill waste. Their hope is to one day run out of waste, as the plant has been designed to be powered by biomass instead of trash; 5 October 2019

Looking to the future of energy production? A Captain looks out from the bridge of a wind farm in the German North Sea. In 2015 Locatelli photographed numerous images with a Leica S, documenting the energy turnaround in Germany; 8 June 2015

LUCA LOCATELLI

was born in Italy in 1971. After studying Information Technology, he worked as a software developer before beginning his career as a freelance photographer in 2006. Within the framework of his work as a photographer and film maker, Locatelli produces his stories in collaboration with journalists, environmental activists and scientists, to better contextualise his research. Locatelli lives in Milan.

LUCALOCATELLI.PAGEFLOW.IO

LOBA WINNER 2020: With the Leica Oskar Barnack Award, Locatelli not only receives prize money, increased this year to 40,000 euros, but also Leica camera equipment valued at 10 000 euros. Within the framework of the Leica Oskar Barnack Award 2020 exhibition, his series, Future Studies, will be on display until February 7, 2021, at the Leica Gallery Wetzlar. The full series and further information: www.leica-oskar-barnack-award.com “You cannot imagine how important it is for me. It’s really great. There are no words to say. It’s a boost of confidence!” says the photographer, finding it hard to contain his happiness after being told he won the LOBA. Speaking with LFI, Locatelli remembers his long journey with this project, which has now reached a delightful high-point of public awareness. Already working on the series for seven years now, he has converted a diversity of subjects into future-oriented global questions and published some of the motifs in previous years. This means he is no longer an unknown in the field of photojournalism, and it was the US American picture editor Alice Gabriner who, acting as one of this year’s LOBA nominators, proposed his Future Studies series for the competition.

When asked what first triggered the series, Locatelli looks back in his career to when his interest in technical innovations inspired him to study Information Technology and then work for ten years as a software developer. “I was already 33 or 34 years old when photography came into my life. From that moment, I fell so much in love with it that I left my employer and my field of work,” he explains. Breaking into professional photography was not easy, yet he remembers a key experience very clearly: “I was in Beijing, trying to capture motifs to reflect the enormous growth in China. In 2006 I was living near the location for the Olympic Stadium, the so-called Bird’s Nest, and through a friend I was able to get closer to the construction site. At that moment I found something even larger than what I had been shooting before. It made me interested in this huge relationship between human, machines and the environment. From then on I tried to discover stories that were related to this theme.”

Future Studies is the outcome of that search and it aims to sharpen awareness about the environmental issues of the 21st century. It centres around future food production, the expansion of cities, garbage reduction, solutions for efficient recycling management and the future supply of renewable energy. From this diversity of subjects, Locatelli compiled his LOBA series with images related primarily to issues around nutrition and the transformation of the energy sector.

The majority of the pictures were taken in Europe because “when you start to dig, looking for possible solutions and the most promising examples of how to confront climate issues, you discover that the north of Europe, in particular, is really like another world. The epicentre is in Europe.” Consequently, he travelled repeatedly to Iceland, Denmark, the Netherlands and Great Britain; and spent over sixty days in Germany in 2015, on assignment for National Geographic, documenting the energy turnaround. “It was a huge assignment. One of the most industrialized countries in the world has a government scheme based on ‘let’s change the way we produce energy’ – with all the errors, mistakes and struggles that implies. I was impressed.”

His images are more than simple documentation: with their compositions and strong colour schemes, they offer unusual insight into otherwise hidden places. Locatelli sees his work as a contribution towards an urgently needed debate about how we want to live in the future. He is convinced that true progress and development are only possible with the lowest possible impact on the environment. “Never before have we had such an opportunity to reflect on what our attitudes should be in the future as we have had during this difficult time of Covid-19, which has brought the world to a standstill. This allows us to consider what our efforts must be in order to re-establish a healthy relationship with nature and the planet,” the photographer concludes. For himself personally, lockdown gave him the chance to take a new look at his subjects, and to start to develop a photo book. He still needs to work on further chapters, meaning that the subject of the future will continue to resonate. ULRICH RÜTER