8 minute read

Feature

Turfgrass Diseases: Summer patch (Causal fungus: Magnaporthiopsis poae)

By Pete Landschoot, Ph.D.

Summer patch, sometimes called Poa patch, is a root and crown disease of golf course turf, home lawns, grounds, and athletic fields.

This hot-weather disease is caused by the fungus Magnaporthiopsis poae and occurs on annual bluegrass, Kentucky bluegrass, and fine fescues. Creeping bentgrass, perennial ryegrass, and tall fescue are highly resistant to summer patch.

Symptoms and Signs

On annual bluegrass putting greens, tees, and fairways, summer patch may begin as small (<4-inch diameter) circular patches that progress to larger (4 to 18-inch diameter) patches as the disease worsens. Large patches will often appear suddenly with no indication of previous disease activity. In severe cases, patches may coalesce and destroy large areas of turf. Summer patch-diseased annual bluegrass initially takes on a yellow color, then becomes brown as affected plants die. On greens, tees, and fairways with mixed annual bluegrass/creeping bentgrass populations, creeping bentgrass will often colonize the center of diseased patches of annual bluegrass.

Symptoms of summer patch in lawns, grounds, and athletic fields typically begin as circular areas of wilting Kentucky bluegrass or fine fescue turf, progressing to reddish-brown or light brown sunken patches, often with a tuft of healthy grass in patch centers. Patches range from a few inches to over three feet in diameter and can appear as a mix of rings, crescents, or spots of various sizes. In severe cases, patches of diseased turf can coalesce, making field diagnosis difficult.

Summer patch symptoms can mimic those of other diseases or turf injury resulting from summer heat stress or drought conditions. Hence, diseased turf should be examined by a qualified diagnostician using a microscope if positive identification is necessary. A microscope examination of summer patch affected plants typically reveals brown, rotting crown tissues and discoloration of the vascular cylinder of roots. Dark brown strands of fungal hyphae (ectotrophic runner hyphae) on the surface of rotting roots, and brown fungal cells inside of root tissues indicate the presence of the summer patch pathogen, M. poae.

Disease Cycle

Dark brown ectotrophic runner hyphae of the causal fungus colonize the surface of turfgrass roots during spring, summer, and fall, but do not typically initiate disease activities until susceptible plants are subjected to summer heat stress conditions. When conditions are favorable for summer patch, the causal fungus penetrates deep into root tissues and invades water and nutrient conducting elements in the vascular cylinder, causing plants to wilt and die. Hyphal strands of M. poae on infected plant debris can be disseminated to other areas via aerator tines, verticutting blades, excavation equipment, or through the movement of soil. Mycelium of M. poae remains dormant during winter in northern climates but can resume growth and disease activities the following summer. This pathogen does not produce spores in the field.

Disease Development

Summer patch usually occurs on susceptible grasses in midsummer during extended periods of high temperatures (> 82°F) following rainy periods. This disease does not appear during the cool weather of spring and fall. On golf courses, summer patch is frequently observed in areas that receive poor air circulation, low mowing heights, heavy traffic, excessive irrigation, and inadequate drainage. In lawns and sports turf, summer patch is often found in pure stands of Kentucky bluegrass or fine fescue turf with wet or dry soils, and in areas subjected to low mowing heights and soil compaction.

Cultural Control

Because summer patch is a root disease, cultural practices that promote good root growth will aid in reducing disease severity. Increased aeration and improved drainage on compacted and poorly drained soils will alleviate some root inhibition and enable turf to better resist infection by M. poae. Low mowing heights are associated with shallow rooting; thus, raising the height of cut may result in less summer patch injury. In some cases, fertilizing with an acidifying fertilizer, such as ammonium sulfate, during spring and fall to lower soil pH may help reduce the severity of future summer patch outbreaks. On golf course turf with persistent summer patch problems, encouraging the growth of creeping bentgrass will reduce summer patch problems. In lawns and sports turf, overseeding turf with a history of summer patch with perennial ryegrass or tall fescue will reduce or eliminate symptom expression.

Chemical Control

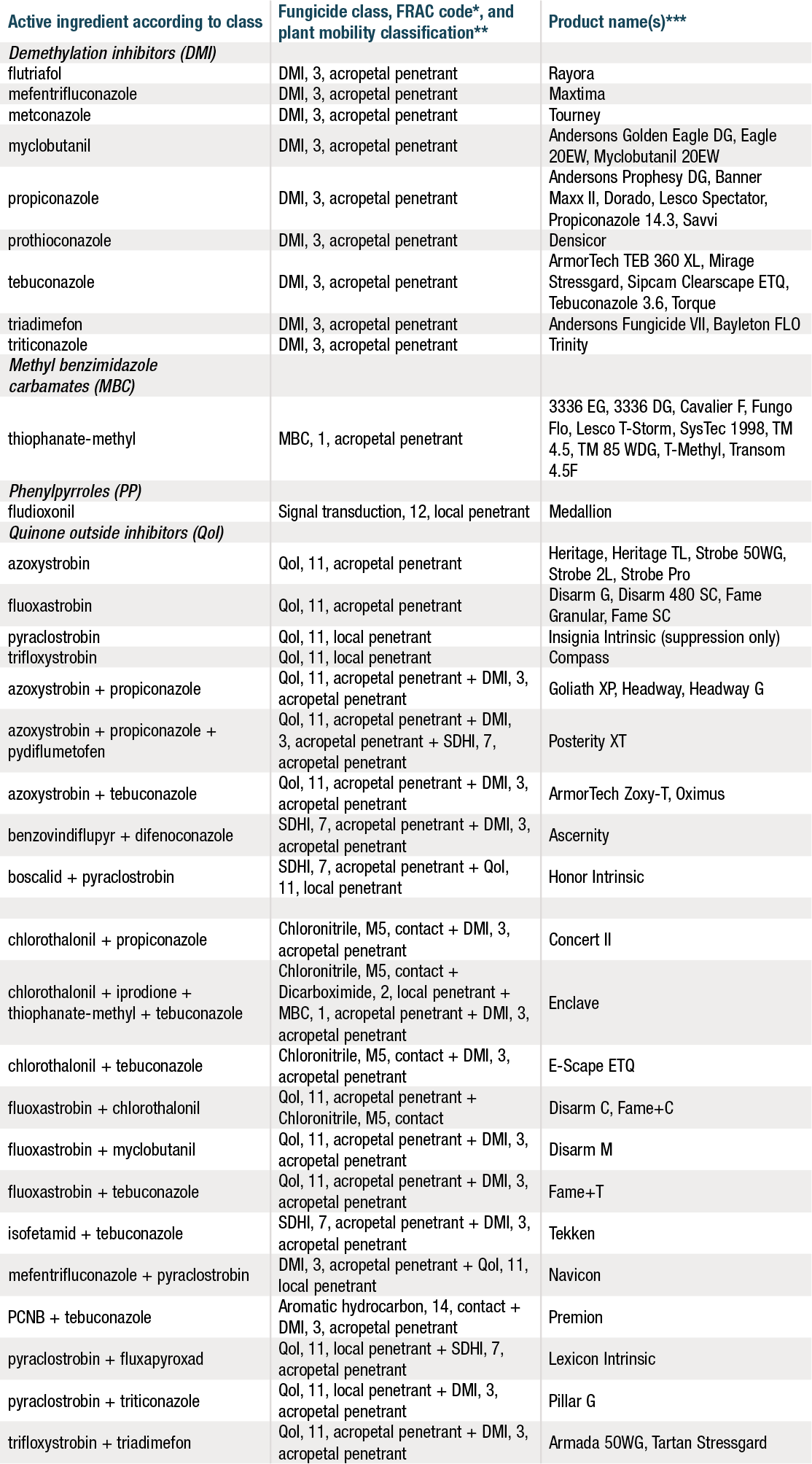

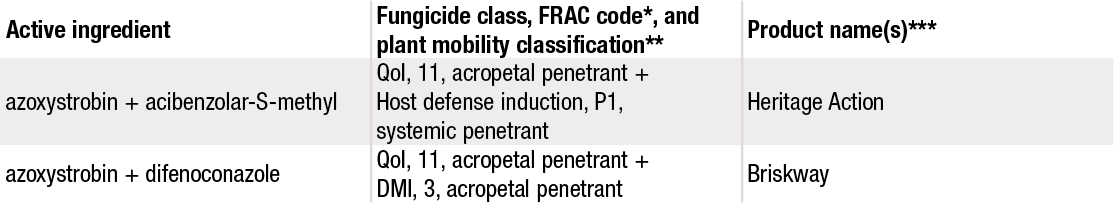

On golf courses, summer patch can be controlled with penetrant fungicides, provided applications are made on a preventative basis (three to four weeks prior to symptom development) and high labelrecommended rates are used. On Pennsylvania golf courses with a history of summer patch on greens, the first summer patch application is usually made between late April and mid-May, with follow-up applications every three to four weeks until August. Fungicides should be applied with large spray volumes (up to five gallons of water per 1000 sq ft) to ensure significant concentrations of active ingredient reach turfgrass crowns and the upper portion of root systems. An alternative to using large spray volumes is to apply the fungicide in the early morning, then lightly irrigate the treated area immediately with enough water to wash spray droplets off the leaf canopy and into the turf/soil surface where crowns and roots are located. Penetrant fungicides in the demethylation inhibitor (DMI), quinone outside inhibitor (QoI), and methyl benzimidazole carbamate (MBC) classes tend to provide the best control of summer patch.

High rates of certain DMI fungicides can produce growth-regulating effects and some phytotoxicity on putting green turf during high-temperature periods in summer; thus, these products are better used for preventative treatments in spring. Preventative fungicide programs for summer patch control are often too expensive for lawns and low-budget athletic fields and may not provide complete control. Turf managers should be aware that “curative” or post symptom fungicide applications generally result in marginal or poor control.

••••••••••

Table 1. Some penetrant fungicides labeled for control of summer patch disease.

Table 2. Some combination product fungicides labeled for control of summer patch disease.

*FRAC is an abbreviation for Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. The FRAC code/resistance group system consists of numbers indicating classes or groups of fungicides based on mode of action, and letters that refer to broad classifications of fungicides (P = host plant defense inducers; M = multi-site fungicides; and U = unknown mode of action and unknown resistance risk). Due to the risk of fungicide resistance, turf managers should avoid excessive use of fungicides within the same FRAC code/resistance group and alternate products among different FRAC codes/ resistance groups.

**Plant mobility classification refers to a fungicide’s ability to penetrate plant surfaces or remain on plant leaf or stem surfaces without penetration. Fungicides that penetrate plant surfaces and are translocated mostly upwards through plant xylem tissues are called acropetal penetrants (acropetal = toward the apex). Fungicides that enter plant cuticles or move limited distances in internal plant spaces, but do not translocate through vascular tissues (xylem and/or phloem) are called local penetrants. Contact fungicides do not penetrate plant surfaces and only inhibit fungal pathogens residing on leaf and stem surfaces.

***Follow label precautionary statements, restrictions, and directions regarding tolerant turfgrass species, rates, and timing of applications.

References

Buhler, W. Fungicide spraying by the numbers.

Clarke, B.B., P. Koch, and G. Munshaw. 2020. Chemical control of turfgrass diseases 2020. University of Kentucky, Rutgers University, and University of Wisconsin.

Latin, R. 2011. A practical guide to turfgrass fungicides. American Phytopathological Society Press, St. Paul, MN.

Smiley, R.W., P.H. Dernoeden, and B.B. Clarke. 2005. Compendium of turfgrass diseases, 3rd Edition. American Phytopathological Society Press, St. Paul, MN.

Smith, J. D., N. Jackson, and A.R. Woolhouse. 1989. Fungal diseases of amenity turfgrasses. 3rd ed. E. and F. Spon, London.