8 minute read

Feature

Turfgrass Seed Production in Oregon

By Scott Vose

Whether you’re building new athletic fields, refurbishing a public park, or creating a new campus environment, you want that green space to provide beauty, enjoyment, and recreation for years to come, meeting the needs of today’s generation while protecting those of the future. This is only possible if your project delivers on all three dimensions of sustainability: Community, Environment, and Economy. Maintaining a successful, sustainable greenspace always begins with carefully selecting the right seed for your property. There are many variables that will determine the outcome of your seed after it is sown, but starting with the highest quality seed gives you the best chance at success for years to come. As Dr. Leah Brilman says, “Don’t plant your problems.”

I was very fortunate to join a trip with my colleagues at Tom Irwin, Inc. in August of 2023 to gain more insight into the process of certified seed production. Our hosts from Vista Seed Partners and DLF led us on tours of their facilities from field to bag and everywhere in between, and it is a much more intensive process than I could have ever imagined. The care and attention to detail that their process requires, before a single seed ever makes it into a bag, is truly remarkable. They feel it is their duty to ensure that the turf managers who end up planting and maintaining their grass seed will be successful.

Growing and harvesting turfgrass seed in the Willamette Valley of Oregon yields very desirable commercially available seed. As much as 80% of grass seed in the world is grown annually in this valley; 400–500,000 acres are dedicated to Perennial Ryegrass seed production alone! In recent years, more production operations have started in Minnesota as well as other parts of the world like Canada and the Netherlands. Canadian/European labeling and testing follow a different process and set of guidelines, and quality of establishment to the end-user may be affected compared to the rigorous testing carried out in Oregon.

It all starts in the field – which we all know as turf managers requires not only experience and specialized equipment, but also a bit of luck with Mother Nature after the seed is sown. Weather is critical from overwintering to pre-harvest, having a direct impact on yield, which drives pricing from year to year. For example, record setting yields occurred in 2021 when weather was ideal, however the following two years had overly wet winters and long drought periods during the growing season which significantly reduced seed yields.

Marissa McDowell of Vista Seed Partners led us on the tours of two turf seed production farms. She explained how if everything goes to plan and the turfgrass matures to produce a seedhead, the harvest timing is determined by scouts, not the farmers. Both farmers we spoke with said that even after 40+ years of harvesting grass seed, they have never had the same harvest date as the seed scouts predicted. The harvested plants need to dry in the field for ten days before being combined. Harvested seed is blown into bags or bins before cleaning occurs; some of the bins we saw housed 250,000 lbs. of raw seed!

A thorough cleaning process is carried out on the raw seed. We walked a multi-level Carter harvester using six screens to sift out weed seed and vegetative material. Between screening different seed varieties, it takes an entire day to clean the harvester/cleaner. Certified turf seed gets inspected by state regulators, who randomly probe bags, therefore each batch (55,000 lbs.) of seed must go to a lab to be checked multiple times throughout the cleaning process. If testing fails, they run through the screener again, always losing a bit of desirable seed on second cleaning.

The seed sample testing process at AgriSeed, Oregon State Seed Laboratory and other accredited verification facilities starts with compiling a paper trail tracking the history of crops previously grown on the harvested field, the specific cultivar that was seeded, any applications that had been made through establishment and other growing environment details. This ensures there was quality control through the entire field production process.

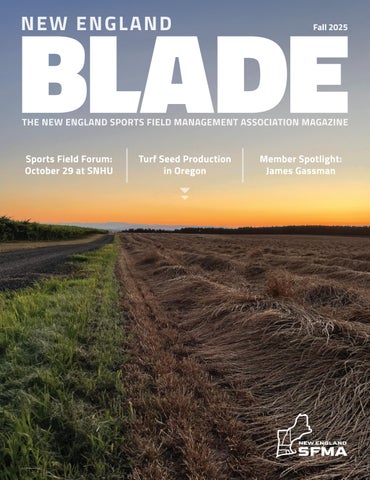

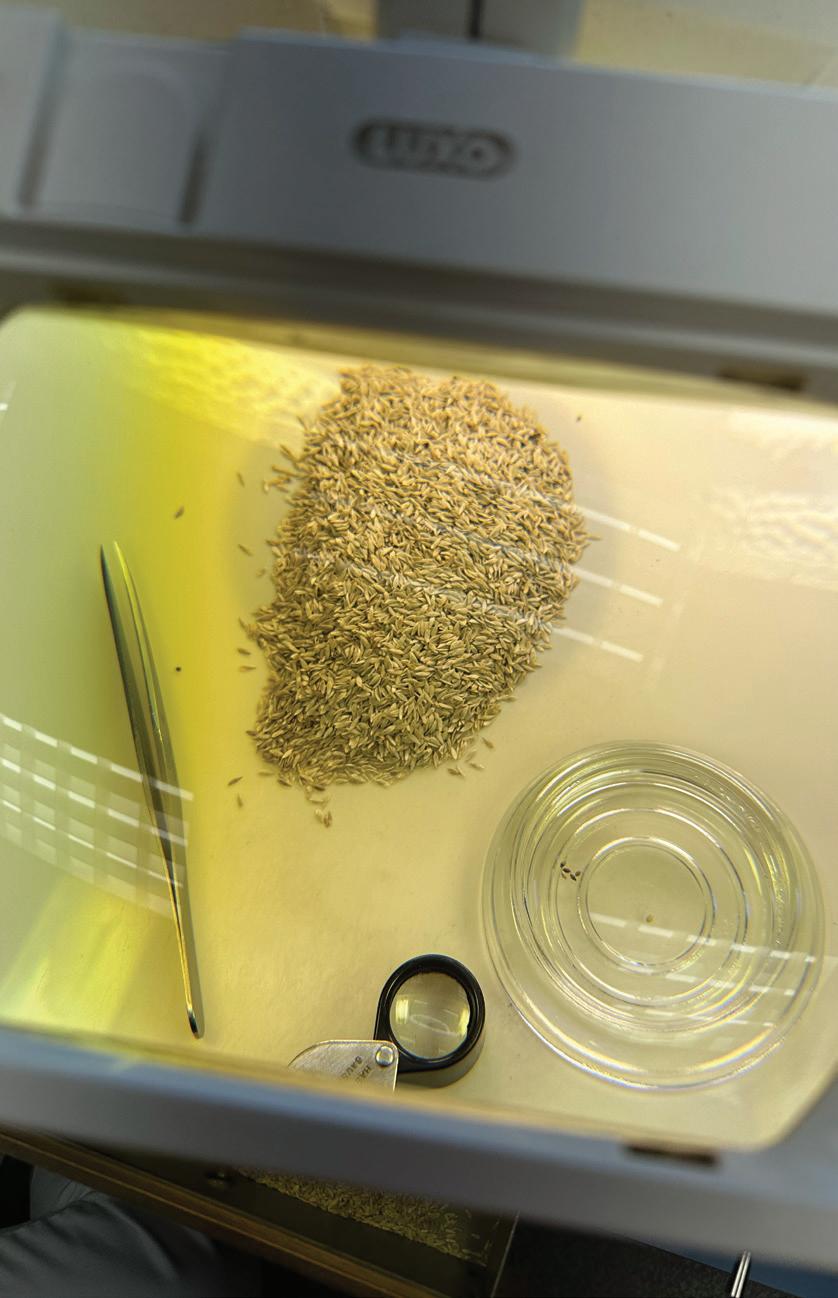

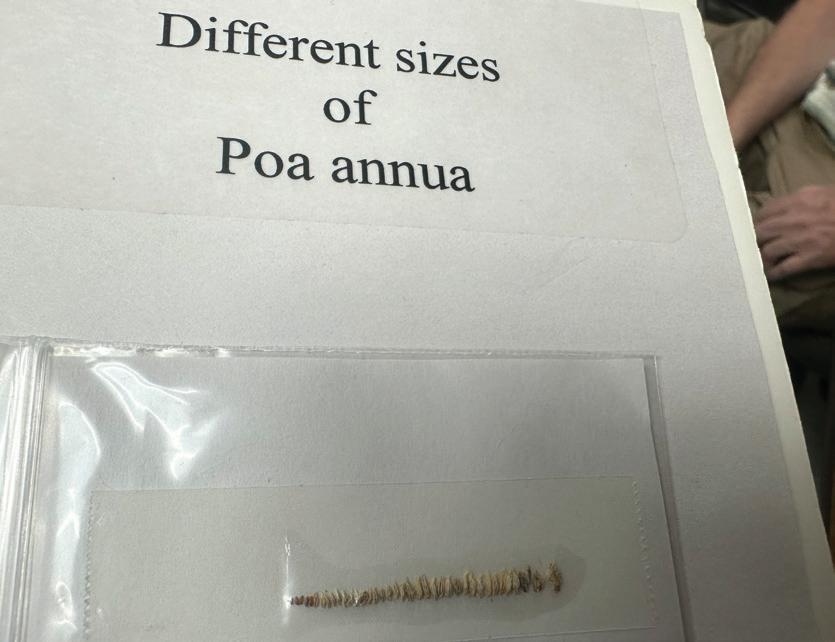

A grower sends a sample of a batch of a particular seed variety to quantify the quality, which is a major driver of price. It is an extremely sterile and controlled process where Sifters first go through 50g samples using microscopes and pull out any weed seed with tweezers to identify it - tedious work to say the least! Any batches with weed seed are either re-screened or end up being sold as lower quality seeds in the marketplace. The samples are then chilled in a room for seven days at 8C to simulate overwintering. An adjacent room is set at 15-20C with grow light cycles to simulate germination conditions on special trays for individual seeds. They also perform a TZ Salt (Tetrazolium Salt) test to see if the turf seed embryos can produce food for themselves (if they do not, they are likely not viable). They are also able to test if Perennial Ryegrass seed is contaminated with Annual Ryegrass seed by assessing the florescence under a blacklight. This is all regulated by the State of Oregon, which has much more stringent quality checks than Canadian and European turf seed regulators.

Once the purity of the seed is validated by Agriseed or another verification authority, the producer can have it certified and labeled for premium quality, then the bagging (and coating) process begins. Every seed production representative we spoke to talked about the importance of coated seed. The DLF bagging facility was in the process of accepting parts for a new single room, fully automated coating, blending and bagging production line to reduce contamination potential. This is a significant quality control investment, as seed that is blended post-production will have a greater potential for weed contamination or loss of viability when it is handled incorrectly. The facilities we toured had storage conditions that were closely controlled and monitored in massive buildings, ensuring the seed remains viable before being shipped.

At Oregon State’s Lewis Brown Farm, there were NTEP trials for Tall Fescue, Kentucky Bluegrass and Perennial Ryegrass. Additional research was being carried out to determine how different coating thicknesses affect germination, and to compare establishment timing of raw versus coated seed.

A highlight of the trip was a tour of the DLF Turfgrass Breeding Facility led by Dr. Leah Brilman. It was truly special hearing Dr. Brilman speak on her home turf as she expressed her excitement for the next generation of cool-season grasses and more temperate warm-season cultivars. She explained in great detail how it can take eight to nine generations to develop a desirable trait consistently in one variety. One generation can take two years, so it could potentially take over 15 years to develop the intended trait fully before production can begin. It is an intricate and controlled process of individual monostand establishment, scouting for desirable traits, cross breeding those plants, and growing consecutive generations until the desirable trait becomes inherent.

As weather patterns shift, it is important that our performance turfgrass varieties continue to evolve. Premium varieties offer the benefits of faster establishment and greater resistance to disease, wear, and drought stress. Secondary certifications on seed blends such as TWCA (Turfgrass Water Conservation Alliance) or ALIST (Alliance for Low Input Sustainable Turf) allow turfgrass managers the opportunity to procure and establish higher performance grasses where there may not be as much supporting infrastructure. Seeding with the right turf species and variety for your property is the first step to successful establishment. Timing for successful seeding is critical - you want to get it right the first time and certified seed helps to ensure you have the best chance of success and are not introducing future problems to your property.

Of course, the laws of supply and demand apply everywhere today, and the Willamette Valley is no exception. If the demand for hazelnuts or another crop increases, more acreage will be converted to nut production than grass seed production. Nuts are grown predominantly on trees, so it is less likely these areas would be reverted to turf seed production once they are converted. Supporting the quality turf seed industry means preserving a vital agricultural economy, protecting rural jobs, and ensuring the continued availability of premium quality seed for sports fields, parks, and greenspaces across the globe. Bottom line: Eat less Nutella, sow more certified turf seed!

Scott Vose is the Technical Advisor at Tom Irwin Advisors, Inc. and is a member of the NE-SFMA board of directors. Reach Scott at scottvose@tomirwinadvisors.com or (860) 428-5294. Photos courtesy of author.