8 minute read

MEET JAMES PEROU

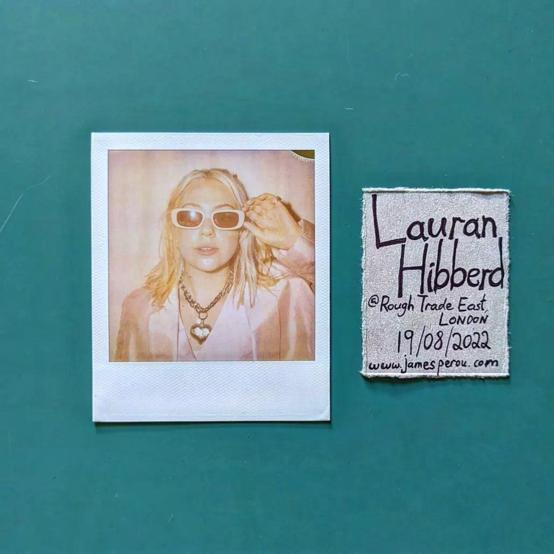

And His Polaroids Of Folk That Make Music

Written by James Perou / Photography by James Perou

Advertisement

If I’m honest, writing a freeform article on my photography series always seemed like a daunting thing. I am definitely not a writer. And it reminds me a little too much of trying to write coursework for GCSE art. However, I want to turn this series into a full book someday, so I was going to have to come up with some vaguely professional copy of my own at some point anyways. I can always plagiarise myself later on.

I think it’s fair to say I’ve got a long-term addiction to Polaroid film. I’m a self-taught photographer who started to take it vaguely seriously while studying engineering at university, shooting gigs in the evenings for the student paper, and then carried on my deep dive into live music once I had returned to London, balancing it with my day job.

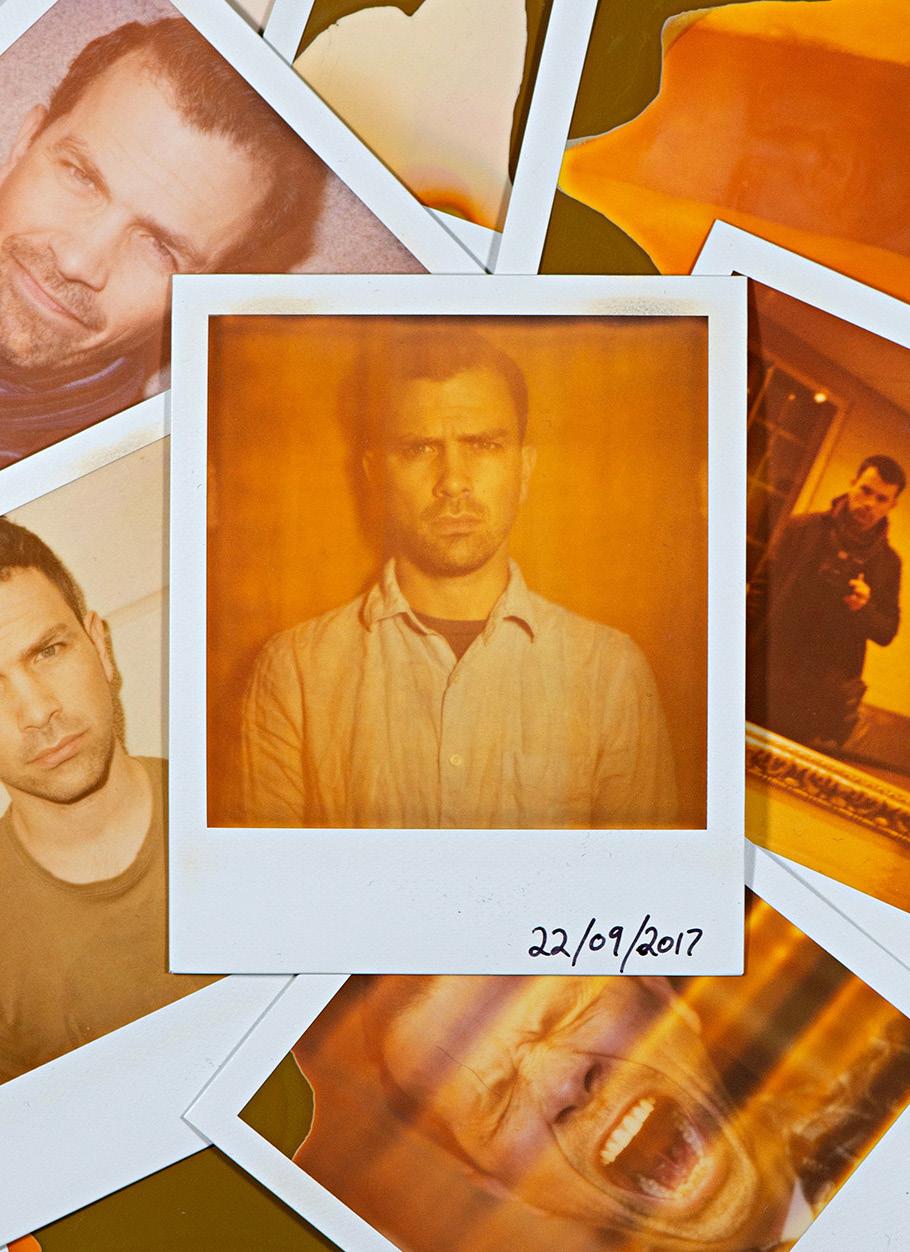

Following a brief hangout in Paris with Blood Red Shoes in 2007, I fell in love with the Polaroid format, stole my sister’s Polaroid 670AF Supercolor, and started shooting everything with it. As I was always trying to do portraits of bands I was working with at their shows, it was inevitable that the streams would eventually cross. The first entries for the “Polaroids Of Folk That Make Music” project were taken on the 14th of December 2007 of the excellent We Are Scientists at the now demolished Earls Court 2, which was acting as the backstage area for the now equally demolished Earls Court 1 when they supported Kaiser Chiefs there.

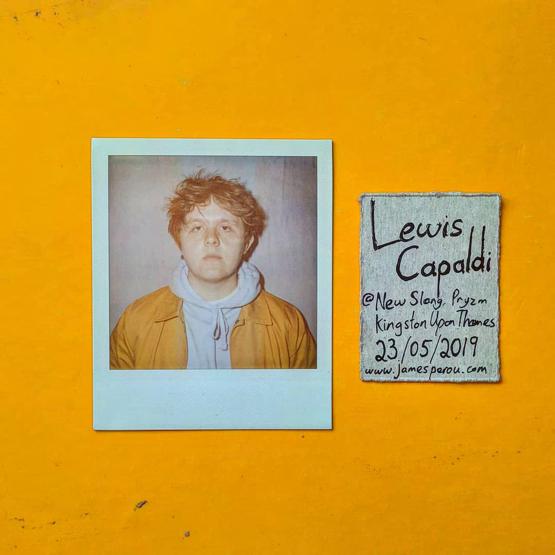

The initial casual shots became a project gradually, over time, as I started taking portraits of other bands I was working with and through my in-house photography work for Banquet Records in Kingston Upon Thames. The project title is a work-in-progress placeholder that has stuck around for over a decade now; I’d seen a segment of “The Play What I Wrote” and liked how the title flowed.

All was going well until February 8, 2008, when Polaroid (under the control of Petters Group Worldwide) announced that the company had decided to gradually cease production and withdraw from analogue instant film products completely in the same year. All remaining film packs from that original production now have a “use before” date of August 2009 at the latest. But I decided I would run the project until the last functioning film was used or had become unusable. I honestly didn’t think it would take another 14 years, but now we’re here at the end; the developing fluid within the frames has all dried out. Whilst some of the last packs will still produce a kind of image, it is too poor to use (and too embarrassing to shoot with).

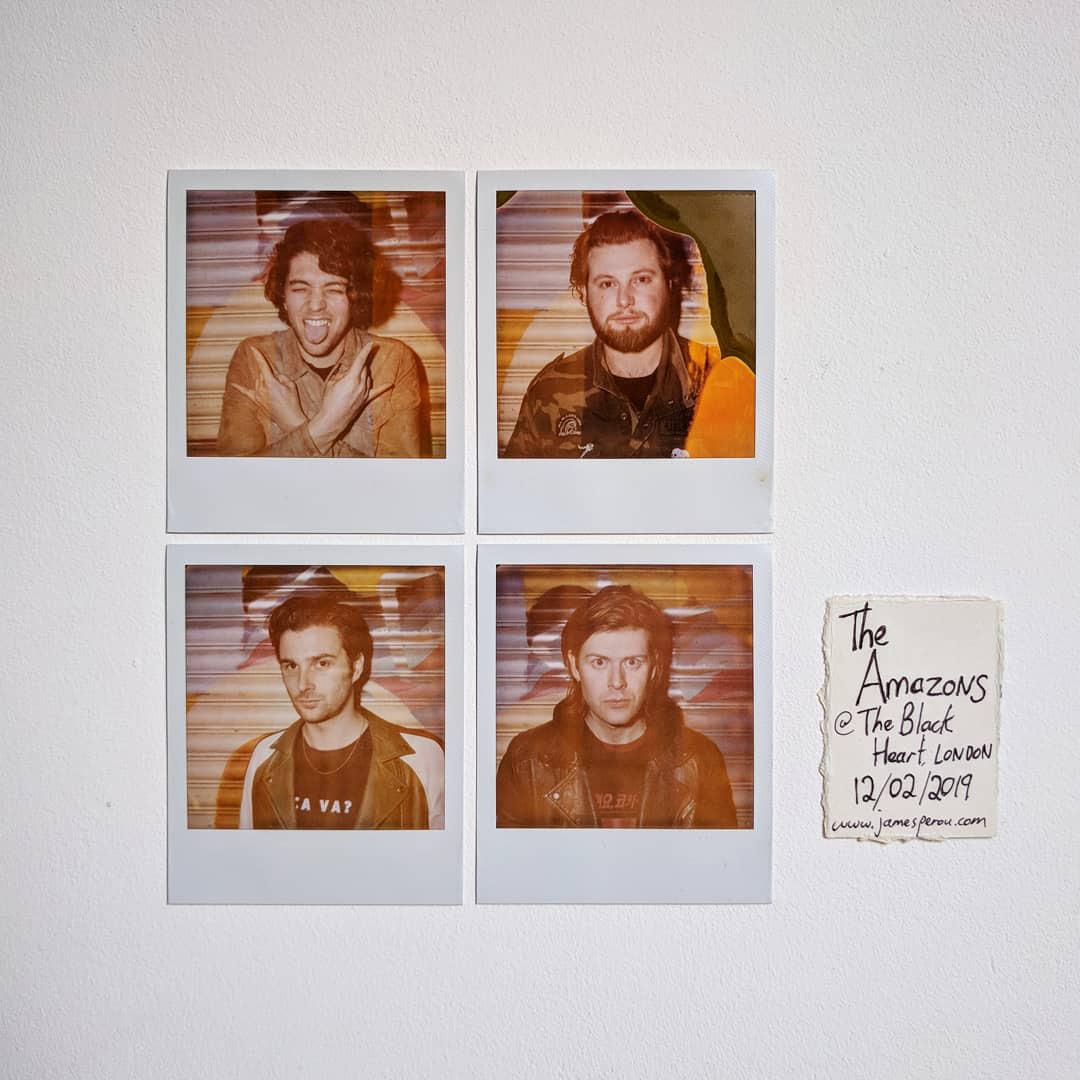

The series format is simple: one polaroid per person per project. So some particularly productive artists are in the series numerous times. The current record is three entries and shared by a number of individuals, including Frank Turner, Joey Cape, Joe Goddard, and James Smith of Yard Act. A benefit of the format is it doesn’t take very long to carry out the shoot, which I think has endeared me to many press reps, tour managers, and bands in the midst of their heavy press schedules. Currently, the project stands at 3050 individual polaroids - I’ve lost count of how many bands are contained within that number.

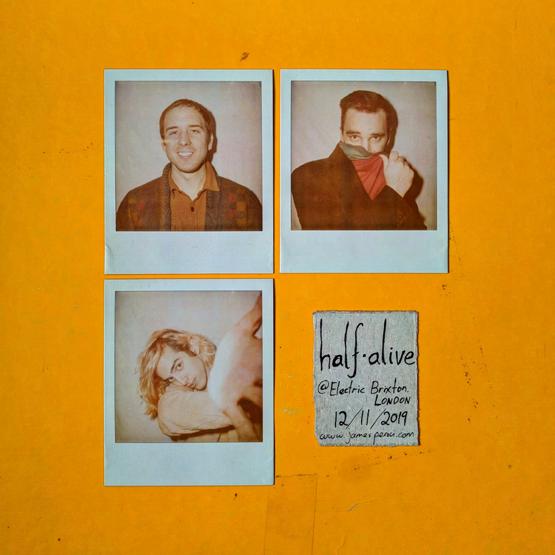

Apart from “stand in front of that wall please”, I don’t give any directions. I often get asked by the musicians whether I want them smiling, serious, etc., but one of the principles of the series is to present everyone equally (and try to avoid gimmicks), so I much prefer to see how they react in front of the camera on their own. Some people are far more relaxed with it than others, and it’s not always who I would expect. I find it fascinating how many artists are more uncomfortable in front of a lens than a crowd, and I love when people take the initiative, as this leads to the more entertaining shots in the series. Two favourites in the series are the joyful Dead Sara guitarist Siouxsie Medley, and Harry Koisser from Peace, who is the only person to ask for an upside-down Polaroid, which I still absolutely love.

The limit of taking a single shot each can be tricky, as sometimes the capture goes awry, and I might not end up with the photo I want. I will always rue the day I missed the shot of Jeff Goldblum staring straight down the lens by a millisecond. Each subject has a veto so that they are happy with how they are presented, but I’ve tried to make that their choice rather than mine. The project has forced me to try and accept what is, rather than what I envision things to be, although I will admit to having done some reshoots when I feel like I haven’t captured a particular person’s presence.

Another challenge is determining what constitutes a band for each entry. Lineups change, some groups are fixed collectives, whilst others may be session or touring musicians formed around a central artist. My approach is to photograph whoever is presented to me as “the band” on the day of the shoot, and I try to not make any later amendments. However, this changes when I’m not able to have access to the full band for reasons of schedule, illness, or elusiveness, in which case I try and collect each member over time. For example, it took almost twelve years to get all of the members of The Specials, the last entry being the much-missed Terry Hall.

In retrospect, this has been a pretty masochistic undertaking for someone who is quite particular, occasionally inept, overthinks pretty much everything, and can be anxious about meeting “cool” people. However, I’d not swap it for anything, and looking back through the shots always triggers good memories: Vanilla Ice talking about fame and how he now spends his days flipping houses, Be Your Own Pet’s super sweaty last show at Dingwalls (until the recent reunion), Big Narstie holding court in his dressing room cabin at Leeds Festival, the buzz of Hayley Williams complimenting my work, or Nile Rogers backstage at Glastonbury being exactly the absolute legend you’d hope he would be.

People often ask me about my most memorable experiences, to which I usually like to retell the story of my most extreme shoot - an attempt to include the Californian superhero band The Aquabats, involving a no-accommodation, no-sleep 36-hour round trip to Groezrock Festival in Belgium, staying backstage till kick-out time at 3 am and walking the 10km back to the local train station in time for the trek home.

Like many creative things I’ve done in my life, it’s only once I’ve done the fun thing that I’ve had to go back and come up with a reasonably artistic-sounding basis for my work beyond “it was fun” (which would make for a much shorter article). Having to create a brief to send out to band reps made me properly think about why I love the format of both the film and the project. I like how each Polaroid becomes a unique artefact when taken; you can take the same shot of the same thing in the same way, but the result will always be two separate physical exposures. There is no negative or digital file to print from; there will never be another copy of the photo you have in your hand - and that makes it all a little bit more special.

Over the years, I’ve found many people have a similar soft spot for Polaroids, which has led to a lot of lovely conversations whilst on shoots; recollections of family history and wonderfully nerdy interests, like talking through Gary Numan’s history of Polaroid uses whilst backstage at the Roundhouse in Camden and discussions about the particulars of the film with Alex Turner prior to The Last Shadow Puppets playing at Alexandra Palace. In general, people seem to be more at ease having their photo taken with it than a regular camera, though I find it interesting just how many artists are far more uncomfortable in front of a lens than an audience.

Now that the film is finally dead, I’m currently finishing the long, arduous task of admin (that I should have done during Covid), to re-digitise the entire collection, and start shopping it around publishers for a book and an exhibition to support it. Originally, that was going to be it, finish the series and move on to other things. But the replacement 600 film originally developed by the Impossible Project (now rebranded as the new Polaroid) has reached a pretty decent state of development, and quite frankly, this is all just a bit too much fun to stop. So, if anyone has any band recommendations, I’ll be starting with “Stage Two” soon…