6 minute read

GREATER CLEMENTS, LCT Review - "First Responders" by Josh Garrett-Davis

AN OLDER WOMAN from my home state of South Dakota told a story that stuck in my memory. She had always regarded her hometown as placid, upstanding, and perhaps she used the word “normal.” Later in life, she volunteered to be a 911 operator, since her town was too small to provide professional emergency services beyond a county sheriff. The calls shocked her. They pulled open the curtains on methamphetamine use, domestic violence, alcoholism, and other dramas. She learned about an expanse of hurt that had probably been there as long as the town had stood—maybe as old as the cottonwood and ash trees in sturdy “shelter belts” or windbreaks nearby. Politeness had shielded the hurt from view.

She didn’t say whether the curtains, the discretion of first responders like herself, were good things. My own parents were both first responders of sorts: my mom a counselor and my dad a legalaid lawyer and public defender. They knew things about neighbors, community members, even my friends’ families, that they never leaked to me. They were also objects of some gossip and discretion, especially after their divorce in the mid-1980s and my mom’s subsequent relationship with a woman—leading, through a cascade of decisions, to her moving to Portland, Oregon, and me staying in South Dakota with a single dad most of the year from ages ten to eighteen. I silenced my urban summers (gay-pride parades, New Age church camp), but in retrospect it is clear that many first responders knew—some local pastors, teachers, lawyers. After graduating from high school, I quickly fled this place where I felt like a lonely outsider, the only one with a secret. From afar, I have spent many years researching the histories and cultures of the Plains and the broader American West. I have felt drawn to dramas of the past—first to historical 911 calls, conflicts, and controversies, but increasingly to subtler incongruities, unexpected creations, and resilient survivals. A central story for American history is what some scholars call “settler colonialism,” what they used to call “the frontier”—the attempt by newcomers to erase and replace indigenous others. This has been a messy process, with an astounding array of both indigenous and settler peoples, and many unclear lines between or across those two simple labels. The stories are rich and seemingly bottomless.

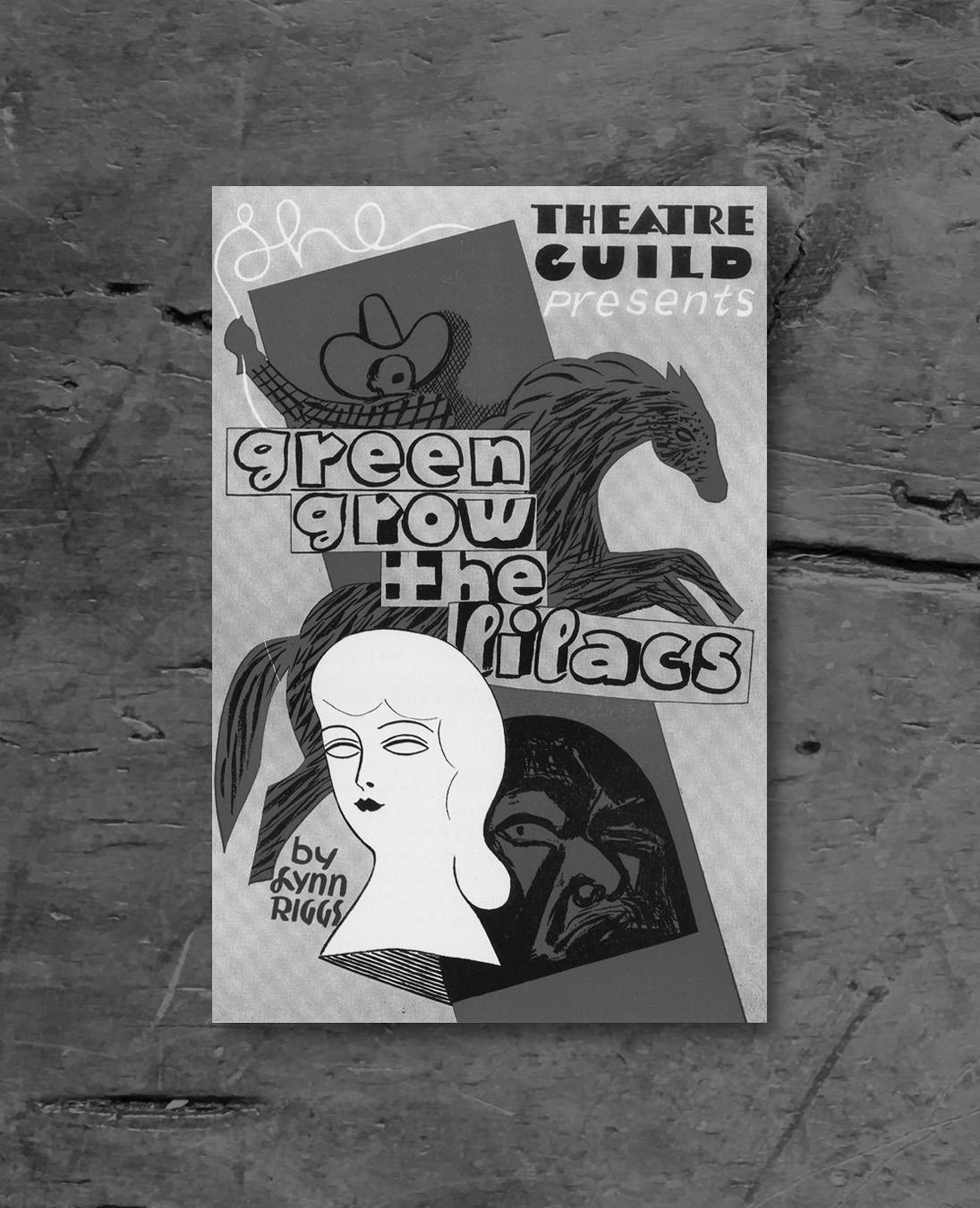

Now I work at a western-history museum that seeks to explore these dynamics, often in tension with popular fictions about the West. We often screen Westerns and try to place them in context with short introductory remarks. Not long ago we showed Oklahoma!, the 1955 film adaptation of the musical. It was stranger than I remembered from the classic Broadway songs and courtin’ story. One confusing element was a stilted, almost tortured regional dialect. It turned out that this writing had survived the translation from the 1930 play Green Grow the Lilacs, by Lynn Riggs, on which Oklahoma! was based. In his foreword to the play, Riggs wrote of striving to capture a “nostalgic glow” around his home state, which he had left as a young man. In his characters’ meticulous dialect, in Riggs’s reaching for something past, something stirs.

When the original play’s matriarch, Aunt Eller, resists the arrest of her nephew by deputy federal marshals, she declares that the United States is “jist a furrin country to me,” with no rightful jurisdiction in Indian Territory. One of the deputies defends himself (“We hain’t furriners”) by asserting, “Why, I’m jist plumb full of Indian blood myself.” Lynn Riggs, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation living (as an adult writer) in exile in that “furrin country,” hinted here at the issues of tribal sovereignty and federal authority, blood and belonging, that can shape personal dramas in the middle of this continent. He also subtly excavated the effects of historical violence. Laurey, the lead character, at one point recounts, “In the Verdigree bottom the other day, a man found thirty-three arrowheads— thirty-three—whur they’d been a Indian battle.” The home Riggs yearned for became home after the Cherokee were forcibly removed less than a century earlier, and a vague violence haunted the landscape. Some prosperous Cherokee brought slaves with them on the Trail of Tears—individuals who were themselves descendants of indigenous African peoples uprooted by a similar system of land theft and labor that then displaced the Cherokee Nation from the southeastern United States to Indian Territory.

Riggs was also gay, and at least one scholar of Native American literature, Craig Womack (Muscogee Creek/Cherokee), has suggested that Riggs, unable to grapple with the queer Cherokee experience, was forced to write in “coded statement.” Maybe Riggs’s sexuality underlay his nostalgia. Maybe, even in the classic musical adapted from the play, the faint shadow of a yearning, queer history of this continent passes by the homestead, noticeable enough to send some of us digging. I sometimes wonder, Whence this desire to dig up hidden or forgotten stories within an often horrifying historical landscape? What was the draw toward the arrowheads in Verdigree bottom (like the tarnish of verdigris itself on bright metal)? I hated history when it was taught as a litany of battles and dates, but I can’t resist it when it breaks my heart.

Late to the scene by definition, the historian shares with the first responder an awareness of some tragedies curtained over in the mimeographed town-history booklets and the smalltown museums that dot the West. Great personal and historical tragedies and survivals hide among the ranch tools and the black-and-white photographs. Depending on our motives and our relationship to the community, we choose a middle ground between tell-all and discretion.

Today it seems that the polite small-town façade has cracked. (Of course, I’m a grown-up now and have access to gossip we keep from kids, and I’m also an outsider to small towns now, with only visiting knowledge of their everyday experiences.) Millions vie to be first responders online. For L.G.B.T.Q. westerners, southerners, or other small-town folks, the love that dared not speak is now out and spoken, if still lacking civil and labor rights. Brave souls speak out against racism and social phobias of difference louder than I ever did. Even lurid sex, drugs, violence—once shameful, now “normal” and even conservative-presidential— have stepped out of darkness, perhaps into the spotlight. Ultimate Fighting Championships, once semi-illegal, are now family entertainment. Neck tattoos are cool at church. People whose parents regarded Bill Clinton as a repellent sexual monster now display Donald Trump’s silhouette on their vehicle windows.

I have scars from the false normalcy maintained by my home state’s myths about itself. For at least a decade after leaving home, I couldn’t speak publicly without a lingering fear or shame, and old reflexes still warp my behavior. I can’t believe I’m wondering this, but, nevertheless, I do wonder, For those who didn’t die of them, did those old curtains or façades have some value? It is both impossible and undesirable to go back in time, to shove people back into the closet, or to unweave the vast wired (and wireless) tapestry of information that connects us. Settler colonialism cannot truly be undone, no matter how much we decolonize. But Lynn Riggs’s possibly coded writing may not have reflected a political or an artistic failing so much as a recognition of the violence we unearth if we dig and dig. As an excavator myself, I hope that more stories are helpful in helping us to understand painful histories, but I also wonder whether I will know when it is best to sing a pretty song and leave the arrowheads in the ground.

JOSH GARRETT-DAVIS is an associate curator at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, and a Ph.D. candidate in history at Princeton University. He is the author of Ghost Dances: Proving Up on the Great Plains (2012) and What Is a Western?: Region, Genre, Imagination (2019).