12 minute read

Features

Wewere in serious need of guidance: How couldwe move from power struggle to compromise? How doyou motivate a deeply ambivalent spouse to do chores?When doyou take a stand on something, andwhen shouldyou let it go? So I called upon three experts who could try to help us reach a resolution. Julie Morgenstern is a New York organizational consultant for Fortune 500companiesandtheauthor of books such as Shed YourStuff, Change YourLife; Gary Chapman, Ph.D., is arelationship counselor and the author of thevaunted 5 Love Languages series; and Darby Saxbe, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Southern Californiawho has studied the effects of stress fromclutter.

First my husband and I e-mailed themalladescriptionofourissues and challenges.Then, in separate phone calls, each pro gave us feedback and tips, and crafted a strategic plan just for us (that canwork for anyone).

Advertisement

Meeting of the minds

It turns out my edginess sparked by mess is not imaginary. Darby Saxbe tells me her scientific research has shown that a cluttered home can disrupt a person’s level of cortisol, the stress hormone. “One of the things that make people have a physiological stress response is feeling a sense of overload,” she says, “and clutter is a nagging reminder of things that are left undone.”

On the other hand, Saxbe has found that, for others, a surfeit of stuff offers security, memories, and even pride. In otherwords, one person’s detritus— Tom’s old concert ticket stubs come tomind—is another’streasure.

So the first step toward marital harmony, says Julie Morgenstern, is to understand each other’s perspectives. “Focus on the person and not his or her stuff,” she says. She tells me to have Tomwalk me through the house,without comment or criticism from me, and explainwhy his systems, as bonkers as they might seem,work for him. “Ifyou ask for a tour in the spirit of seeing it through his eyes, itwill change your relationship to the situation,” says Morgenstern. “Youwill understand that he simplyviews his stuff differently than youdo.”

It never occurred to me that there couldbesomelogicbehindhishabits, not just sheer laziness.Tom points out thatthevariouspaperskyscraperson his desk are needed every day for research.The closetwhere he keeps his five (yes, five) bikes is chaotically bursting, but he shows me that he knowswhere every item is. Boxes are stacked by the front door as avisual reminder to take them to the post office. (Even though, after a few days of nonaction, I end up being the reminder.) He even provides a semi-credible reasonforthesuitcasethat,oneweekafter thetrip, is still not unpacked.

Hisexplanationsdodial downmy irritation a tad, and his suitcase rationale actually makes me feel a little sorry for him. “So he does have a methodology—it’s just not thewayyour system operates,”Morgensternexplains.

In the same spirit, I askTomwhy, after he makes a sandwich,itlooks as if our refrigerator has exploded. “Forgetting about the prep things,” he says, “is like a form ofwhat psychologists call ‘inattentional blindness’:You don’t seewhatyou’re not looking for.” (Tomwrites about science and psychology, sohereallytalkslike this.)

Fair enough. But then Morgenstern has mewalkTom through the kitchen after he has barreled through it to make a sandwich so he can see my perspective. “Show him how upsetting it is that his mess costsyou time and keeps you from doingwhatyouwant to do,” she says.Wewalk past the scattered utensils, the bags of bread, chips, and turkey, and the empty lemonade carton. I point out that because the kitchen now looks like the Gorilla House at the Bronx Zoo, I’m going to spend 10 minutes cleaning,when all Iwanted to dowas make a cup of tea. Not to mention thatwhen he leaves containers open andwanders off, the food can getstaleorspoil—whichcostsus money. He is abashed. He promises to make an effort from now on to straighten up as he goes. But just in case, I try one of Gary Chapman’s suggestions and ask him, “Would it be OKifIleftyou anote tocleanup,or wouldyou take that as me beingyour mother?” (“A request is always better than a demand,” says Chapman, so asking, and providing options,will boost my chances of results.)Tom is finewith it, so I hang a small note on the kitchen bulletin board that reads, PLEASECLEANASYOU GO.

TOM:

“OK, yeah,it does pretty much look like a crime scene.”

TOM:

“Thatsuitcase is a grim symbol of a fun trip that has ended.

Delaying unpacking prolongs the pleasure of being away.”

TOM:

“Youmakethe sandwich; you want toeat the sandwich.

Youdon’t want to be returning food toits rightful place as thesandwichsits, beckoning. In my head, I’ve already moved on to thenext stage: eating the sandwich.”

A clothes encounter

One of our most squabbled-about issues isTom’s bedroom closet: It’s stuffed so full that he can’t even close the door. I’ve been pestering him to shovel it out for the past six months. Chapman suggests an opposite approach: “Don’t mention the closet again. He already knows thatyouwant himtocleanitout,becauseyou’ve told him 15 times.” Instead, he tells me to giveTom a compliment every timehedoesanotherchore,liketaking out the garbage or helping my daughter putawayLegos.

“Butwhy should I praise him like he’s a golden retriever for things he should be doing in the first place?” I ask. Chapmanlaughs. “I hearyou,”he says. He explains that this advice applies to either gender and is not about bolstering a mate’s ego but about establishing an atmosphere of kindness and respect,which is ultimately a more fertile groundforeffectingchange.

It still feels retro to me.When I grumble thatTom doesn’t compliment

Dirtylaundry

RealSimple staffers—some onTeam Messy, most onTeam Neat—share their biggest pet peeves.

TEAM MESSY

• Making my bedwhile

I’m still in it • Clearing my drinkwhile

I’m still drinking it • Clanging dishes late at night (because cleanup justcan’t wait) • Mandatedshower squeegeeing • Premature disposal of the newspaper • Vacuuming under my feet. (“Excuuuse me!”) • Putting away shoesthat were deliberately left bythe front door forthe next use • The question “Hey,where do you want this ______ togo?”

TEAM NEAT

• Uncapped toothpaste • Unidentifiableblackcords (“just in case”) • Hundreds of extra lightbulbs (“you never know”) • Soggy cereal clogging the sink • Snacks put back in half-sealed Ziplocs • Inside-out clothes in the hamper • Wearingshoesthrough the house after mowing the lawn • Piles of loose change • Crumbs onthe computer keyboard • Microwavingwithout a cover • The coupons-and-receipts drawer • Half-used shampoo bottles • Takingout the trashbut not replacingthe bag • Holding onto leftovers way toolong • Leaving wetstuffin the washing machine • So many pens! me on these things, Chapman says that I can’t keep score. I just have to suck itup,giveapproval generously, and wait. “As simple as that?” I ask, incredulous. “None of uswant to be controlled,” he says. “IfTom is feeling like you really care about him,with affirmingwords, he’s far more likely to be motivated to clean out that closet.” And once all the goodwill has been established,knowingthat Iwant this task done,Tom just might surprise me.

Twoweeksinto forcingmyself to praise my husband, right after Saturdaymorning pancakes,Tom stands in front of the closet, hands on hips, and says it’s “time for a rethink.”Then—this sounds too easy, but it’s true—he cleans it up. He tosses ancientT-shirts, arranges sweaters, and thins out duplicate items, likefourcampingheadlamps.

Digging out his closet took most of the day, but he did it all. I askTom later if he had noticed that Iwas pouring onthecompliments. Hehadn’t.

Sigh.Well,itworked,anyway.

TOM:

“Thisis just optimization: Let the water do the work.”

TOM:

“I have multiples because you throw things out! Remember when we wereabout to leave for

Europeand we finally found my missing passport in the trash?

Nothing is safe, so I stock up.”

Managing the mess

Energized,IconsultSaxbeonanother perpetual skirmish: I like towash the dinnerdishesimmediately, while Tom prefers to “let things soak.” Andsoak. It’s not until right before bed,when I’m fully enraged, that he ambles over toputthem inthedishwasher.

Saxbe says I need to loosen up my time frame. “Ifyou give him ownership of the dishes, and he can do them in whatever time frame hewants, then you don’t have tobe actively stressed that they’re inthe sink,”shesays.

But this brings on some twitching, so I take Chapman’s advice and tell Tom that I’m not going to nag—I’m just going to trust that after he has let the dishes soak, he’ll follow up and put them awayby,say, 10P.M.Heagrees.

This ideaofmeeting in themiddle is the key to managing our dynamic, say all three experts.They tell us that one of the most important thingswe can do isto letgoof thethinkingthat either one of us is “right.” So I hold my

TOM:

“Why do I have to do it all at once? If I’m doing a school drop-off, do Ihave to tackle asagging trash bag, too?”

tongue whenTom doesn’t take out the recycling I’ve left by the doorwhen hetakesourdaughtertoschool.

I ask him if he feels any annoyance that the task is still hovering over him. He admits he does, and says he feels betterwhen he is on top of tasks but finds it just too tough to stay neat.

Working toward a détente, Morgenstern has us pick no-go areas,where Tom can slob out and I get to be immaculate. He claims his bedside table,desk,andbikecloset;Iclaim the kitchen counters, dresser tops, and bathroom cabinets. She also has us contain as much ofTom’s flotsam as possible.To quell his habit of dropping everything at the front doorwhen he gets home, for instance,we hang hooks for his coats and bags and put a covered seagrass bin by the door to dump everything else in (papers, books, sunglasses). I’m still irritated knowing there’s a mishmash of stuff in the bin, but covering itwith a lid is helpful: If I don’t see the mess, it doesn’t trigger anytwitching.

Breaking the cycle

We then move on to the laundry— impetus of many a clash.Tom is a cyclistwho generates mountains of sweaty exercise clothes, so he’s in charge of thewash.The problem is thatheletsthebagswelltoaMacy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade float before he dealswith it—and by the time he has, I tell Morgenstern, the clothes have basically turned to mulch.

For fraught situations, she likes to have clients ask themselves a question to gauge if it’sworth the ire:What does itcostyou?“Like,withthelaundry bag,” she says, “what does it costyou, other thanyour obsessive need to not have it pile up?”Well, itreeks, I tell her.Also, at a certain point, I run out ofunderwear.

“Right. So those to mewould be legitimate reasons.Whereas ifyou’re thinking, I hate to see something pile up when it could be getting done, that’s emotional. That’sathing whereyou have totakeyour eyesoffthe stuff.”

Morgenstern suggestswe swap our ever expanding bag for a “beautiful hamper that’s smaller, so it fills faster and has a lid to contain odor.”Then she asksTom if there is anythingelse that bugs him about laundry, and he says “matchingsocks.”

“Oh, the biggest obstacle,” she says. She suggests thatwe get socks all in one color to eliminate the matching task. “Unlessyourwhole thing is ‘Iwear cool personality socks,’ just screw it,” she says. “Who cares?”We don’t. So we ditch our socks, hop ontoAmazon, and order black ones for him and gray forme.(Ourdaughtergets tokeepher animal-festooned “personality socks.”)

Terms of agreement

The progress is promising, but there’s still another source of bickeringwe haven’ttackled:Tom’shabitof losing hiskeys at least a few timesweekly. I point out that he is not so easy-breezy when he’srunning lateforameeting. As Charles Duhigg noted in his book The Power of Habit, to change a habit you have to make a new habit. Morgensternsuggestsgettingaprettycontainerand putting it by thespotwhere Tom most frequently tosses his keys, which is a tableby thecouch.I find a little leopard-print bowlwith a gold rim on One Kings Lane.The plan doesn’twork. Sowe buy him the TrackR Bravo, a $30 coin-size gizmo thatyou can attach toyour key ring so you can quickly hunt it downwithyour phone. His phone basically grows out of his hand, so no chance of loss there. As for me, Morgenstern says I need to get a handle on my endless tidying. The point of staying organized, she tells me, is to free up my time so I can spend itdoing the things I lovewith family and friends. Instead, it seems I devote waymoretime to cleaning andstraightening than I do to having fun. Saxbe agrees. “Ifyour need to clean up is interferingwith thingsyou enjoy, that’s maladaptive, meaning it stopsworking foryou,” she says. “Inwhich case it’s time to rein it in.” Now,whenwe’re playing a family game of Monopoly and I’m tempted to leap up and put something away, I ask myself, “Can I stay in the moment instead? Can it wait?DoI needtodo itat all?”

WhatTom and I learned pretty rapidly in this experimentwas that, as Chapman puts it, “eitheryour spouse cannot change, or for some reason, he orshe willnotchange. That’s whenyou’ll have to realize that it’s not any great crime that there are stacks of paper all overyourhusband’sdesk. It’s not logicaltoyou,butitworksforhim.”

So I’ve stopped harping aboutTom’s messy desk. Instead, I ask him (instead ofcommanding him)to endevery workday by at least squaring the piles into tidy stacks to give the illusion of neatness,andtostashlooseworkdetritus in a cabinetwith the door closed. And I now ask myself, “What does it costyou?”multipletimesaday.This ingenious little phrase delivers instant perspective.We still have our disputes, butwereallytrytosee things from the

other’s point ofview.

And I have begun to get that constantly patrolling thewastebaskets to see if they need emptying is not much of a life. Do Iwant to live in a showroom, or do Iwant to live in a home? Instead, I trywhenever possible to adoptTom’s philosophy of life,which appearstobe“Letit soak.”

TOM:

“You’rethe type who straightens up out of habit.

But for me, it’s like an event

I haveto gear up for: Get the Spotify playlist ready; gather the supplies. It’s easier toput it off—or not do it at all.”

TOM:

“Ijustdon’t know if Iwant space in my brain takenup with real-time geo-locational tracking of my keys.”

TOM:

“It’s actually a categorical filing system. All papers go together in one paper-themed vertical storage unit.”

TOM:

“Turns out, her clean-upas-you-go approach isn’t as toughas I thoughtit would be. I’ve found it’s better for my stress levels to be more proactive rather than flying into crisis modeat the last minute.”

Jancee Dunn isthe author ofthe upcoming advice book How Notto HateYour Husband AfterKids (available May2017).

Linguine with broiled garlic and clams

Produced by Sarah Copeland Photographs by Marcus Nilsson Food Stylingby Victoria Granof Set Design by Jeffrey W. Miller

HOT TIP

The heat of a broilerturns out extra-crispy skin on smaller cuts of chicken,like legs and thighs. (Larger pieces will burn before the meat cooks through.)Place thicker parts toward the center of thepan, where the heat is concentrated.

Broiled citrus chicken with mushrooms and onions

Quick broiled eggplant dip

HOT TIP

A broiler mimics the direct, searing heat ofa grill, so ingredients like eggplant and tomatoes get a charred, smoky flavor while the insidesstay soft.

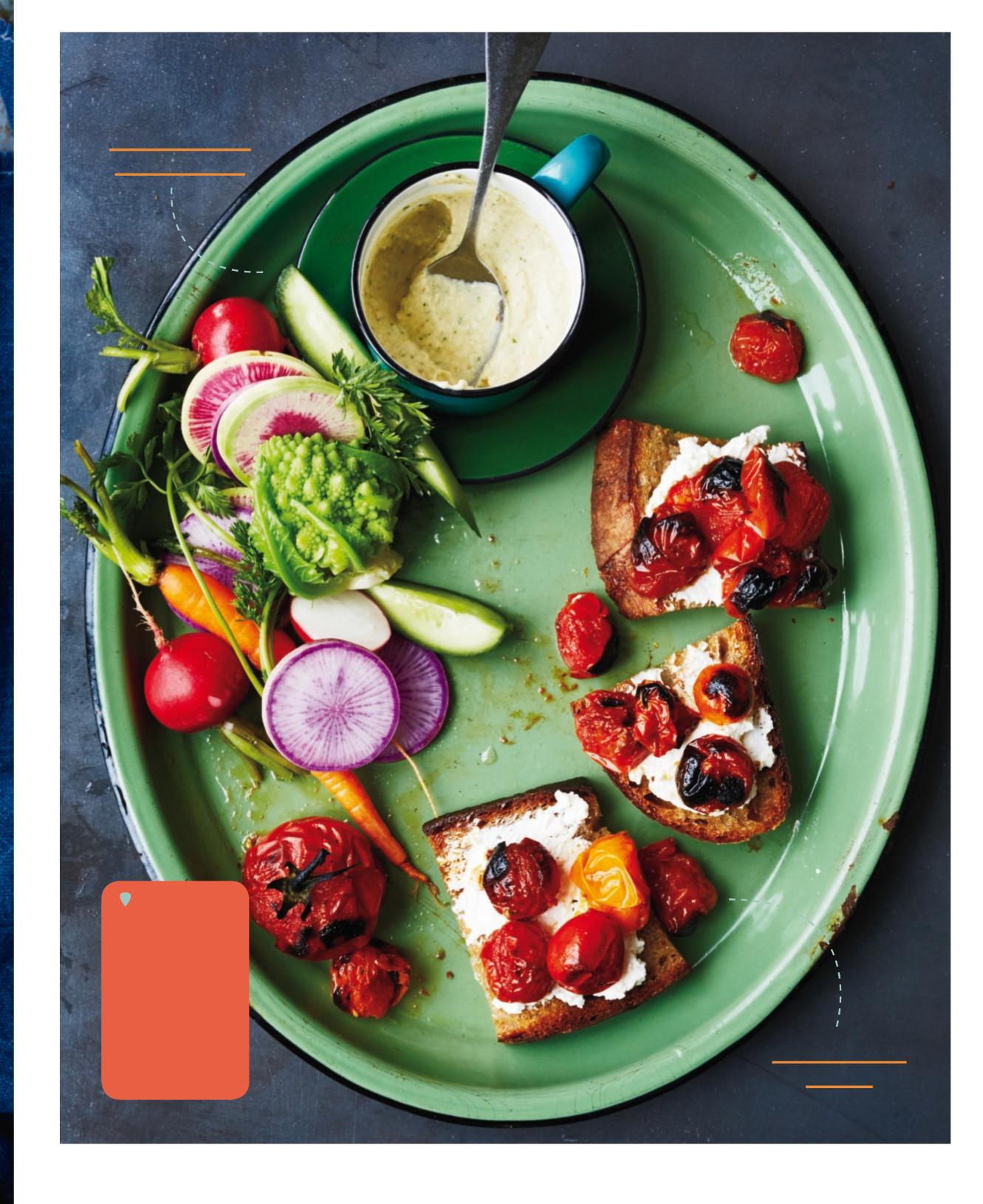

Burst-tomato toasts