7 minute read

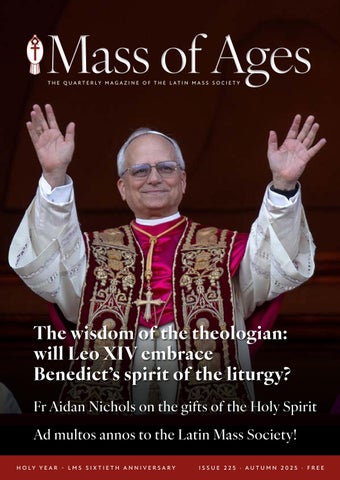

The wisdom of the theologian

Will Leo XIV embrace Benedict’s spirit of the liturgy, asks Dr Fredrick Wolf

While praised in many circles for his ‘discretion’ and diplomatic character, Pope Leo XIV’s theological positions on many subjects remain largely unknown. Francis was elected on a mandate of reform; Leo received the Fisherman’s ring to continue reform but foster unity and communion in a polarized and fractured Church. Will the new pontiff accomplish this through the modernising orientation of his predecessor or will he embrace the wisdom of the theologian, Benedict XVI? After all, they both ultimately desire the same for the Church – unity and communion. The theologian seeks it through continuity with previous church councils – let’s pray the new pontiff does as well. There are unconfirmed reports that he privately celebrated the Traditional Latin Mass.

The work of Benedict and his pontificate is generally not well understood. And this is particularly true with his post-Vatican II reform efforts. These centre on changing how we understand the liturgies and the ambience experienced with their celebration. In effect, Benedict calls for a ‘new liturgical movement’.

This article will illustrate Benedict's approach to the challenges facing the Church – which some attribute to the promulgations of Vatican II. Joseph Ratzinger’s response was otherwise – advocating, instead, a ‘reform of the reform’.

Will Leo embrace continuity in the context of Francis’ modernising legacy or as Benedict sought with his hermeneutic of continuity with Vatican I and II? This could define the pontificate of Leo XIV.

Reforming the Reform

The crux of Benedict’s response to the issues confronting the Church (and now Leo) is his hermeneutic of understanding of the Second Vatican Council. If the Council is viewed as a break with the Church’s past, then the new reformed liturgy is seen as a break with the pre-Vatican II liturgy – a ‘hermeneutic of discontinuity.’

If the Council is seen in substantial continuity with tradition, then the reforms which it promulgated must be in continuity with the older form of the liturgy – a ‘hermeneutic of continuity.’

Benedict asserts that, paradoxically, a minority of traditionalists and most modern liberals appear to make the same mistake: both view the Council as a break with tradition. He emphasized that the Council did not represent a discontinuity; rather, it expressed continuity with the Church’s history.

If one looks at the Council as the genesis of something new, then understanding the liturgy as a newlycreated entity that – evolves with the culture – elicits a ‘hermeneutic of discontinuity’ – a break with the past. Conversely, a ‘hermeneutic of continuity’ understands the liturgy as truth transmitted through tradition with the Church possessing no authority to manipulate or distort it. Changes are appropriate, but only when consistent with prior Councils, Scripture and the Magisterium of the Church.

It is untenable for the Church to have, as it were, two hearts: one lifted up to God, the other turned away. ‘Come not unto Him with a double heart’ (Ecclesiasticus 1:28). By analogy with

James 1:8, the Church cannot be ‘doubleminded’ and thus ‘unstable’. Through the hermeneutic of continuity, Benedict's efforts at ‘reforming the reform’ has meaningful purpose. Contrary to some who misconstrue his intent, Benedict's reform centers on helping us properly understand the liturgy, its purpose and meaning for us and the spiritual ambience surrounding its celebration. It does not mean we reject the Novus Ordo; rather, Benedict wants us to understand the purpose behind it – an appeal for unity and reconciliation – however misguided its distorted, overzealous implementation. It is in this context that Benedict initiates his call for a new liturgical movement: ‘…a movement toward the liturgy and toward the right way of celebrating the liturgy, inwardly and outwardly.”

Benedict initially seeks to quell innovation as the primary thrust in the liturgy. With this Pope the liturgy should be centered on God – and nothing else. Rather than a liturgy celebrated with the celebrant facing the people, Benedict encourages celebration ad orientem (towards the East) – a Christological orientation. This gesture of priest and faithful pivoting in unison towards Christ underpins an understanding of the liturgy and our lives as being towards God. At the same time, it undermines the idea of a ‘human-centered’ ritual, all too frequent in today's Church.

The issue of orientation in the liturgy, Benedict asserts, should be combined with some Latin in the Ordinary Form. He understands that the ‘Liturgy of the Word’ is usefully addressed in the vernacular, but the use of Latin in other areas of the Mass would bespeak the catholic (universal) nature of the Church’s Extraordinary Form –continuing its tradition. The idea is to contribute to the mutual enrichment of both forms which Benedict spoke of in the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum.

The final component of Benedict’s liturgical reform is the idea he made manifest as Pope through his Summorum Pontificum. The promulgation allowed a more expansive use of the Tridentine Mass which, he believed, would offer tangible benefits towards unity in the Church.

This Pope’s intent was to reconcile the Church with those troubled by certain of its ‘experimental innovations’ because of liturgical or other concerns, as with

The

Society of St Pius X. Use of the older form of the Mass, the Pope believed, would also help maintain continuity between Vatican II and its antecedents.

Liturgical Renewal

As Pope, Benedict (the former professor of theology) emphasized his role as educator, rather than inculcating structural reforms into the liturgy. His teaching revealed themes present throughout his ministry – a liturgy with God at its center; the nature of the liturgy as a conveyance of established truth; the transcendent dimensions of the liturgy.

For Benedict, it is not about changing the rites again (this would redouble the mistakes of the last six decades); rather, he wanted to change how we experience the liturgy – and allow it to change us.

This Pope did not simply want to restore the past ad orientem practice, but to institute reform in continuity with the past. He does not advocate that the entire Mass be celebrated ad orientem; rather, only a portion – the Eucharistic liturgy proper – where the priest leads the faithful to turn towards God, in unity and communion.

Reform of the Reform – an error?

As much as Benedict advocated reforms consistent with but not beyond Vatican II promulgations, Pope Francis’s disinterest in the content, spirit and intent of the Second Vatican Council’s Sacrosanctum Concilium was glaring. The Pope referred to Benedict’s efforts disparagingly (before his death) saying: ‘to speak of “the reform of the reform” is an error!’.

Yet, in spite of Francis’s liberal agenda, Benedict the theologian defends the Council's actual promulgations – not the radical extremes and hyperbole that overzealous modern liberals have imposed upon the Church faithful.

Benedict asserts that Vatican II promulgations were not a break with previous Church teaching regarding Vatican I and before; the Church, by her very nature, cannot break with her own past. To suggest that previous teachings were flawed, and we are just now ‘setting them straight,’ is to deny that the Church is and always has been guided by the Holy Spirit.

To understand that the Church remains under the continual guidance of the Holy Spirit, is to understand the validity of Vatican I and II. To do otherwise is to forsake Christ's words in Matthew 16:18-19, the apostolicity and catholicity of the office of the Pope and to our great detriment – the very nature of the Church, itself.

This writer believes Pope Benedict XVI hoped we would see his own contributions less in terms of his concrete proposals and more (as he wrote in his book – The Spirit of the Liturgy) as a retrieval of the latter – and its central role in the life of the Church as well as our own lives.

Let us pray that Leo XIV pursues unity and communion through the wisdom of this profoundly Catholic Pope, Benedict XVI, by following a ‘hermeneutic of continuity’ allowing the traditional liturgy and timeless sacraments of Christ's Church to manifest in us through sanctification – similitudo Dei –the likeness of God.