10 minute read

NEED TO KNOW

by LABI_Biz

1

4

2

5

FREE ENTERPRISE WASN’T FREE

LABI was first launched to battle for better business competition

BY MARY BETH HUGHES

3

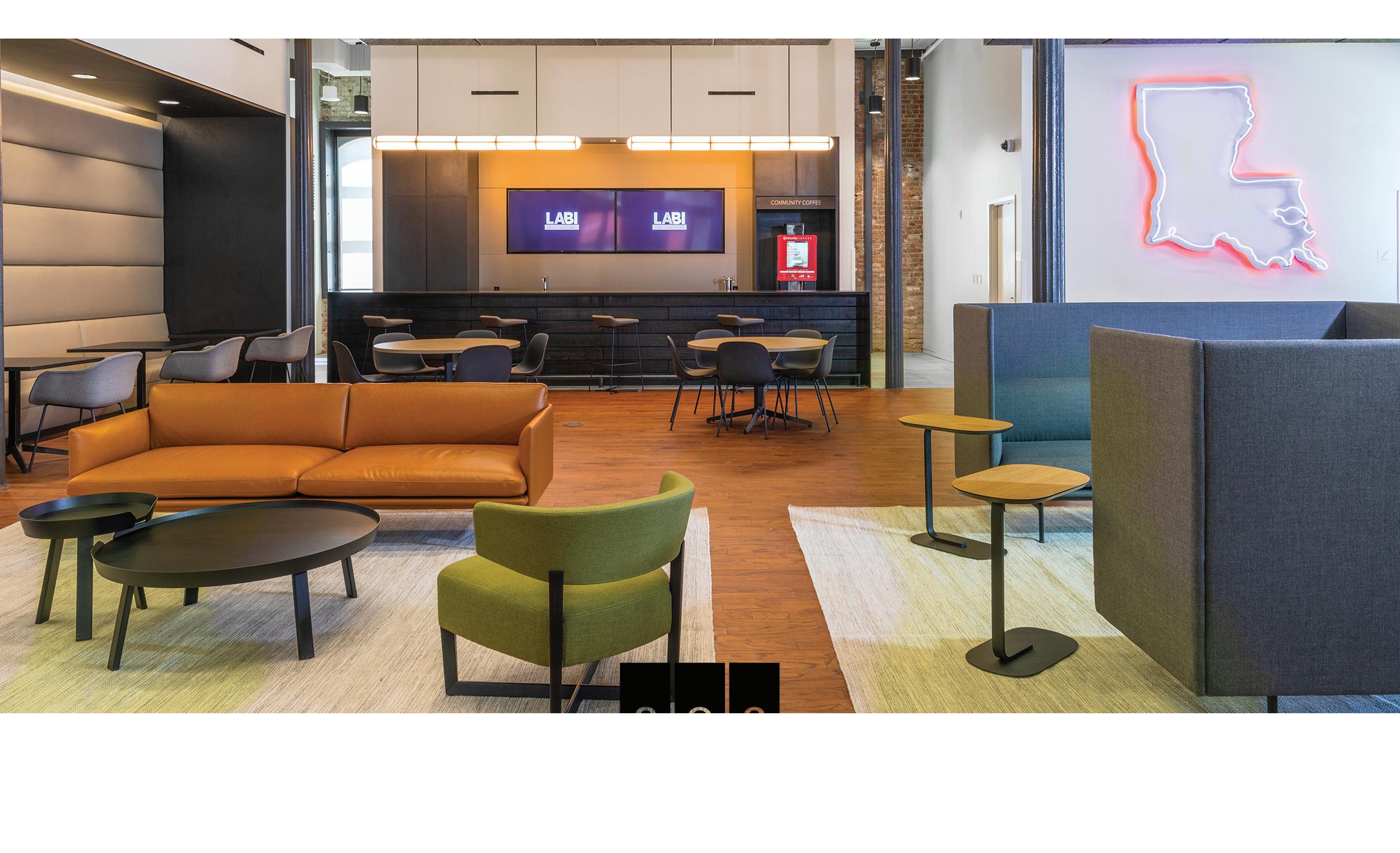

“Walking into the Roumain building felt like 1920s Chicago. The atmosphere, the old tile. A creaky elevator that took us to our offices,” says Jerome Vascocu, remembering the downtown Baton Rouge building. “I wondered if we were in over our heads.”

The year was 1976, and Vascocu had just shown up for his first day at the newly formed Louisiana Association of Business and Industry (LABI). He and Steve Ridley, a newly hired labor relations lobbyist, arrived at the Third Street office at the same time.

In 1974, a group of business leaders from across Louisiana joined forces to correct an imbalance that had developed in state politics over the years. The mission was to improve the business and political climate across Louisiana. However, each leader belonged to a different organization, each with its own priorities. Still, they all had the same goal: to unify the business community into one strong organization which could speak for business and industry.

“They recognized that we needed a mega organization. One voice for business,” says Lane Grigsby, founder of Cajun Industries. “The combining of the chambers and industry was an intellectually gifted move.”

And so, three became one. Officers of the Louisiana State Chamber of Commerce, the Louisiana Manufacturers Association and the Louisiana Political Education Council agreed to merge their memberships, funding, and staffs into one association. In 1975, LABI was born.

Perfect partnerships were in place,

6

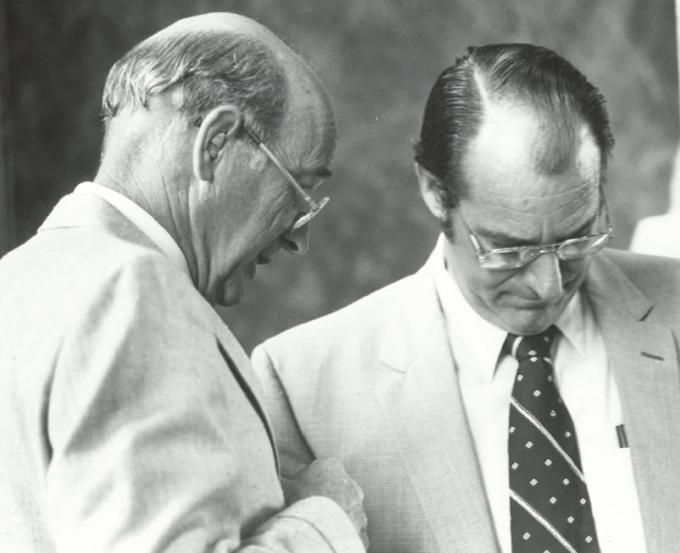

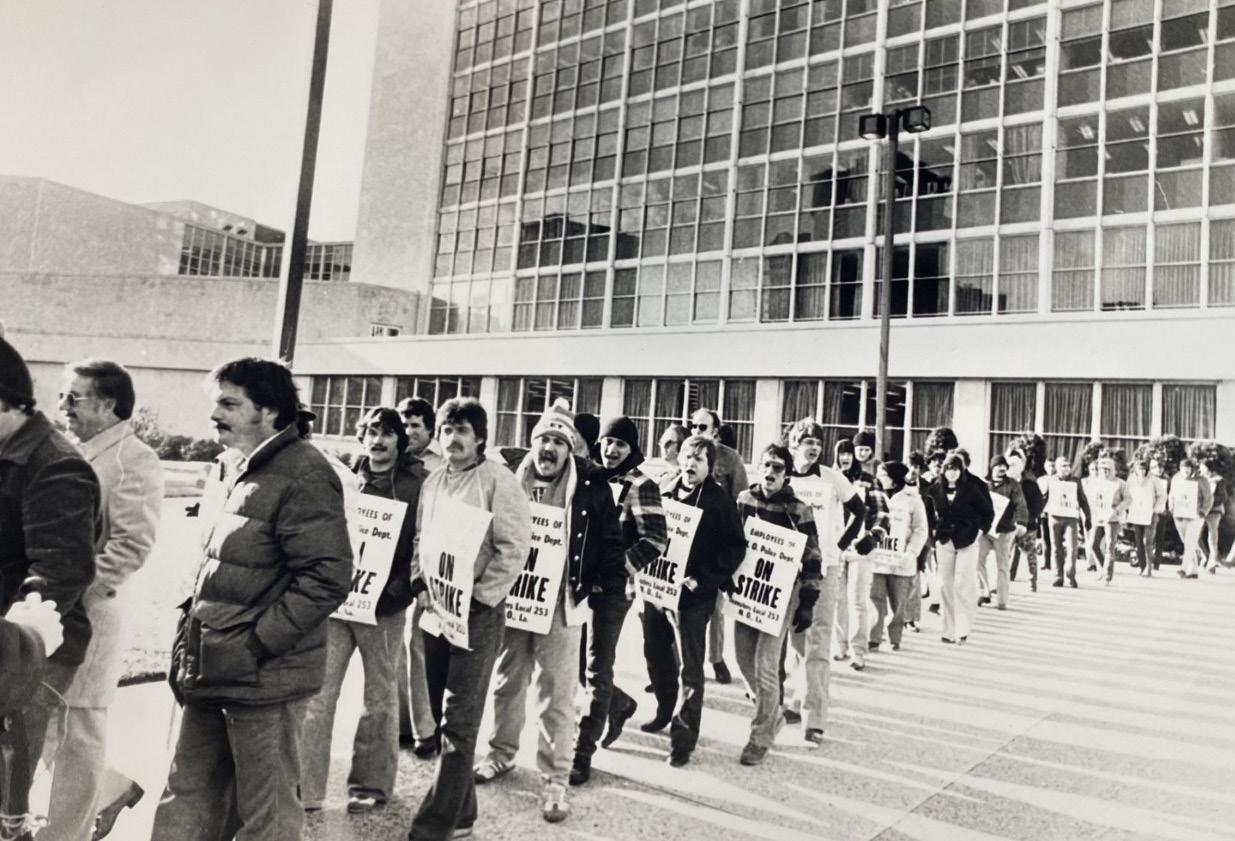

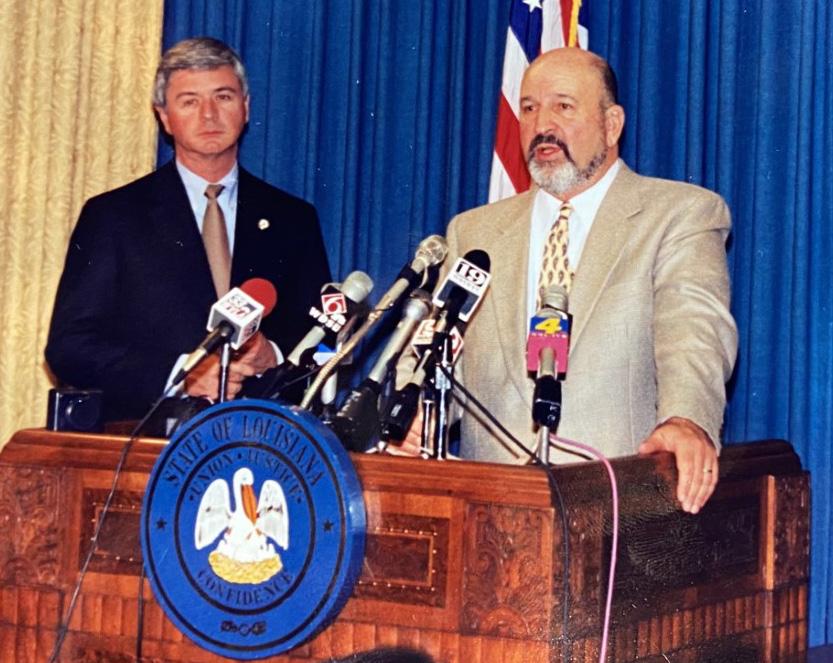

1. Ed Steimel speaking with State Senator Allen Bares. 2. The Roumain Building, 1920s. 3. Police bracing for protests near the Capitol. 4. Union protestors near the Capitol building. 5. Organized labor protesting outside of the Louisiana State Capitol. 6. Ed Steimel speaking at Capitol House.

Ed Steimel but the executive committee recognized that a strong leader was imperative. They needed someone who could stand toe-totoe with the powerful head of the state AFL-CIO, Victor Bussie. The position called for someone who would be resolute and fearless. They decided that Ed Steimel was the man for the job. Steimel had served as the executive director at the Public Affairs Research Council (PAR) for 20 years and had established himself as voice for smart policy reforms, never backing down from a fight. He would go on to serve as LABI’s president for the next 14 years.

“Ed had a very clear vision of what he wanted for the organization,” said Jimmy Burland, who was hired to lead LABI’s PACs in 1984. “Ed was a visionary, but he’d light a fire under your butt.”

It was Steimel’s reputation that ultimately became the deciding factor in Vascocu’s decision to join the LABI team. He was offered the position of assistant to the president, but Vascocu was a north Louisiana man with a family in Ruston. He would have to move four hours south. He sought the advice of his father-in-law, George Holstead, who was a state representative at the time.

“He told me, ‘It’s going to be hard work,” says Vascocu. “But if you work for Ed Steimel for a few years, that’s the equivalent of getting a Ph.D. Ed is that brilliant.’”

First up on the agenda for the newly developed organization was passing a Right-to-Work law: A goal the business community had unsuccessfully pursued for over 30 years. At the time, Louisiana was the only southern state lacking this law which created a stronghold for organized labor. The Right-to-Work law guarantees workers the freedom to hold a job without a mandatory union membership. “The unions controlled everything,” says Grigsby. “Industry couldn’t make any money due to union control. Right to Work put LABI on the map.”

Steimel put together a coalition that included politicians and organizations from across the state. He also brought on advertising guru Jim Leslie to spearhead a grassroots effort that included a $300,000 TV ad campaign. But not everyone was on board.

“So many political folks told LABI not to do it,” Vascocu remembered, “But we were determined to get it done. It was an unbe-

M A N U FA C T U R E D I N T E R I O R C O N S T R U C T I O N | C O M M E R C I A L F U R N I T U R E | S T O R A G E S O L U T I O N S | I N S TA L L AT I O N + S E RV I C E

lievable feat.”

The fight to pass Right to Work began at the Capitol in June of 1976, and it wasn’t without controversy. Right off the bat the House Labor Committee was forced to move into the House Chamber because over 500 people showed up to the Capitol for the hearing. Ultimately both the House and Senate labor committees, on orders from then Governor Edwin Edwards and state AFL-CIO President Bussie, tried to kill the bill. It only made it out of committee and to a floor vote because LABI used a procedural maneuver to force the committees to discharge the bill to the full body.

On the heels of this move, chaos ensued as union members descended on the Capitol in droves to protest the vote. Death threats were made against LABI’s leader. Steimel had to receive State Police protection.

After a fierce battle throughout the month of June, Right to Work passed, scoring LABI its first major political victory. The bill was sent to the governor’s desk on July 8th, 1976. It was signed the next day because Edwards had promised the public he would sign it if the bill made it to his desk. He had been so sure that it wouldn’t when

Police restrain union protestors.

DOING THE RICE THING RIGHT!

Working together with LABI to create a shared, collaborative vision for the future of free enterprise in Louisiana.

Kennedy Rice Mill, LLC | Mer Rouge, LA 71261

he made that promise.

At the time, many considered the Rightto-Work win to be a fluke, a temporary setback for the unions, and it was met with great aggression. Standing on the steps of the state capitol shortly after the vote, Bussie told thousands of his followers, “We’ll keep coming back until this law is repealed, until we can change this terrible day.”

Thankfully, repeal of Louisiana’s Rightto-Work law never came—even though bills were routinely filed to do so throughout the late 1970s into the 1980s. Organized labor, with Bussie still at the helm, made its last serious attempt to effectively repeal Rightto-Work in 1992, during Edwards’ last term as governor. LABI defeated the effort on the House floor following a rare Committee of the Whole that Bussie had demanded, and legislation to repeal Right to Work was never seriously advanced afterward.

No longer at the mercy of organized labor, Louisiana businesses and industries were able to thrive. “Because of Right To Work, the industrial growth in Louisiana caused a ripple affect across the Gulf Coast,” says Grigsby. “Industry in south Louisiana has become the gemstone of our state.”

The passage of Right to Work gave LABI the platform and credibility to become a political powerhouse and the voice for business in Louisiana. In the years following, the policy wins stacked up, membership increased, and LABI’s role expanded.

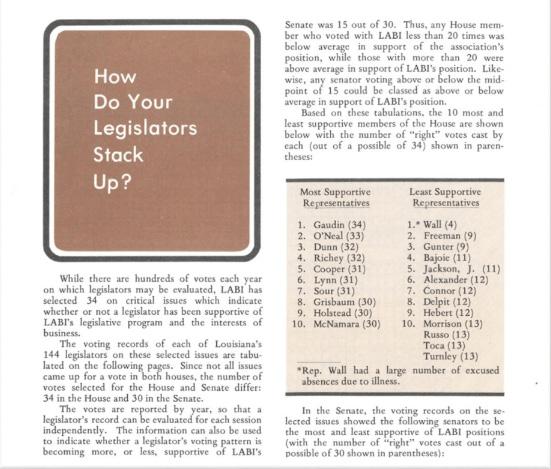

Dedicated to holding politicians accountable to their constituents for their votes, LABI created the first-ever Legislative Scorecard in 1978. The Scorecard is a report that breaks down each legislator’s voting record on bills that benefitted business and serves as a tangible way for voters to keep track of how their legislators vote. Politicians couldn’t afford to ignore LABI.

While LABI spent the 1970s and early 1980s playing defense against the unions’ attempts to repeal Right to Work, the 1990s saw a different battle with a new opponent. LABI helped spearhead Louisiana’s first-ever tort reforms, working with Governor Mike Foster to fight the powerful trial bar.

SEPTEMBER 4TH, 1975:

LABI was officially formed and the first board officers were elected. Ed Steimel became LABI’s first president.

1978:

LABI created the first-ever legislative scorecard, a publication breaking down each legislator’s voting record.

1990s:

LABI worked with Gov. Mike Foster to reform Louisiana’s bankrupt Workers’ Compensation system and create the LWCC.

1970 1980 1990

JULY 8TH, 1976:

After a fierce battle throughout the month of June, Right to Work was passed, scoring LABI its first major political victory. The bill was sent to Governor Edwin Edwards’ desk on July 8th, 1976 and was signed the following day.

1985:

LABI breaks ground on the first official headquarters.

1989:

Ed Steimel retired and was replaced by Dan Juneau as LABI’s president.

1999:

LABI’s PACs endorsed Foster’s re-election over Congressman Bill Jefferson. He won with 62% of the vote.

“In the ’90s, the union’s influence waned and the trial lawyers stepped in. So we focused on tort reform,” says Burland. “And we won that too.”

In the 2000s, LABI worked with Governor Kathleen Blanco to pass significant tax reforms and in 2011 was part of the coalition that passed the most sweeping education reform legislation in history. It was clear that LABI was a voice that was listened to.

It’s been almost 50 years since its inception and LABI is still winning. During the first special session in 2020, LABI’s continued push for tort reform delivered a measure that will reign in excessive litigation and the costs it generates for Louisiana businesses and citizens alike. Then, in the 2021 legislative session, LABI scored one of its biggest legislative victories to date with significant tax reforms that, with voter approval, will help streamline sales tax collection, as well as deliver a simplified tax code with lower income and franchise tax rates.

“LABI’s voice is as loud as ever. It’s the dominating voice,” said Burland. “Someone’s got to protect business.”

And it’s the love of Louisiana business and free enterprise that fuels LABI’s members and allows the organization to maintain an active presence for pro-business, pro-economic growth policies at the Capitol. Not all Louisiana businesses are members of LABI, but all businesses in our state benefit from the active voice and influence LABI has, along with its commitment to create a better, more vibrant and competitive place to work for everyone.

“I’m prouder than I’ve ever been,” says Grigsby, a longstanding member on the LABI Board of Directors. “We were a rag tag group of guys with BB guns. Now we’re a sophisticated group that’s shaping society’s future. This isn’t short term, it’s long term. LABI makes a difference.”

2004:

LABI worked with Governor Kathleen Blanco to pass significant tax reforms.

2013:

Dan Juneau retired as LABI’s president and was succeeded by Stephen Waguespack.

2021:

During the 2021 legislative session, LABI scored one of its biggest legislative victories to date with major tax reforms.

2000 2010 2020

2011:

During the Bobby Jindal administration, LABI was part of a coalition that passed the most sweeping education reform legislation in history.

2020:

After helping to elect the most business-friendly legislature in 2019, LABI passed the most significant tort reform legislation since the 1990s.