3 minute read

C O L O R S A coda in

by LABI_Biz

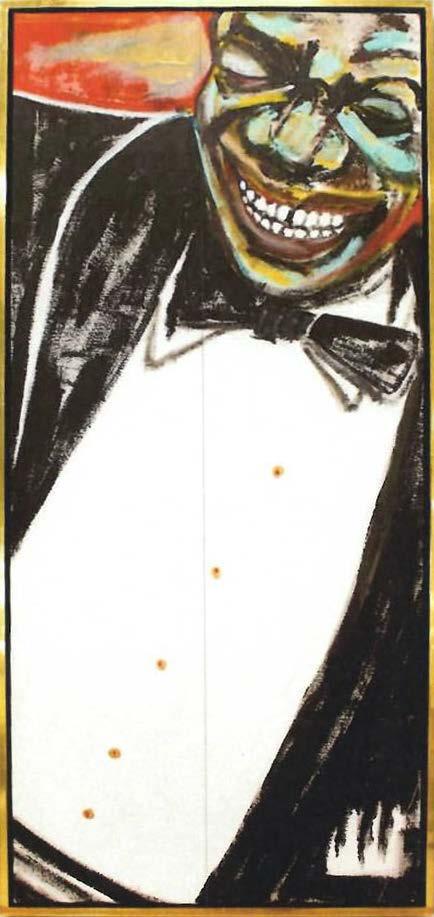

Frederick J. Brown’s vivid paintings reflect Louisiana’s jazz and blues identity

BY JEFFREY ROEDEL

WATCH THE FACE of iconic melt into his horn, merely a fluid extension of his arm, as a mosaic of colors frame his visage like stained glass would honor a saint, and the message is hushed but clear. This is church. And the spirit is moving.

The creator of this vision, Frederick Brown, was drawn by jazz, not art, to New York City in 1970. The Georgia-born, Chicago-raised painter first connected with radical sax god Ornette Coleman, and soon they were hosting a rotating salon of artists, musicians and seekers at their lofts—collections of creatives that rivaled Warhol’s Factory.

“He was very open and kind to people which made him magnetic,” says Brown’s son Bentley Brown, an artist, art historian and educator at Fordham University. “His art was reflecting the force of the community he was cultivating.”

That community often looked like a dreamland of jazz.

Saxophonist James Jordan once called Brown’s loft an exciting place and “the start of a journey” for his career.

As his entry into creativity, Brown thought sound had a lot of color in it. That’s a sentiment that can’t just be reasoned out. It has to be felt.

The jazz of our modern minds often gets boxed into museums, and historic buildings and hallowed halls. A beautiful starting point, but too often, there it sits, safe and unsounded.

That is, until you find yourself on Frenchman Street, or walking past Preservation Hall, or in the buffet line at a wedding reception, or in your kitchen, half-awake in wrinkly pajamas, and you hear it. Louis Armstrong is on and your body starts to sway and shake.

It’s then that jazz is not just in the blackand-white patina of a picture frame, or in the rusted curves of brass nailed up to a wall. It’s in your blood, and in your soul. And when it gets in there, your feet begin to move and your heart begins to dream.

That’s when the song really begins.

These songs now have another life with Universal Heart Chords: Music Paintings of Frederick J. Brown, now on display at the New Orleans Jazz Museum.

“In his scale and his use of color and shapes, Frederick Brown brings his own sense of lyricism and creativity to the paint, much in the same way a jazz musician shapes and interprets a song or a solo,” says David Kunian, New Orleans Jazz Museum Curator.

Brown’s paintings challenged the notions of traditional portraiture head on, both in subject and in style. Bentley Brown views them as avant-garde, made at a time when black artists were never labelled as progressives—though Ornette Coleman, Miles Davis and others fit the bill.

“It’s identity confirming for me as a

Black man who grew up in Arizona,” he says. “I see an aspirational energy that inspired me to realize you can exert your force upon the world.”

From Louis Armstrong to Buddy Guy, jazz and blues icons and sojourners alike shine in Brown’s vivid portrayals.

“Those are an act of ‘spirit conjuring,’” recalls Bentley Brown. “That’s what we would call it in the studio. The music hits in a certain way, and these are spiritual projections.”

The very idea of jazz is translated and transcended in Brown’s explorations. The medium is different, but the essence, feeling of a stroke of the brush and the stab of a horn, can be the same.

“He was portraying these Black folks at the peak of their moment and in the best light possible,” Bentley Brown says. “Rewriting the narrative on portraiture by having audiences understand that these folks here are the bedrock of American culture, not just Black culture, but American culture. That’s the commentary. That’s the vision. And to use the language of Rembrandt to do that is a powerful statement.”

For the documentary 2003 120 Wooster Street, filmmaker Tony Ramos described Brown as a synergistic source of inspiration for all in his orbit.

Whether at his 1970s SoHo loft or commanding a creative cavalry for his massive retrospective (the first from a Western artist) at the Museum of the Chinese Revolution in Beijing in 1988, Brown was a masterful storyteller, and a humble leader.

“Freddie has this way of gathering around himself these incredible people, and then it generates its own thing,”

Ramos said.

Though he died in 2012, the Frederick J. Brown Trust, the work of his son, Bentley, and galleries like the New Orleans Jazz Museum, ensure Brown’s work is still doing just that: gathering and generating Kunian says the galvanizing strength of the paintings leaps out of the frames with an undeniable energy that mirrors the power of the music itself. The same jolt that influences every aspect of New Orleans culture, and moves people to sway and shake and dream.

“Most of all,” Kunian says. “It overwhelmingly tells the viewer that jazz is still so alive and vital—especially in New Orleans.”

How