4 minute read

Activism or an aesthethic?

Konsta Lindi

The multi-faceted flop of a musical Rent is an interesting rendition of the time-honoured classic story: We’ve been left behind by the system. The rework of Puccini’s La bohème dabbles in the trials and tribulations of two well-off white kids in a love triangle whose lives are burdened by the nuisance of having unconditional love bombarded at you by your worrying parents and having your black queer friends around you die of aids. Paired with authentically 90s pop rock, it is a spectacle one has to see to believe.

Now, I am but a petty bitch with far too much time on my hands to hate on lazy storytelling, but I must ask you to bear with me just a little bit longer.

What made La bohème work, the then brand-new notion that poor people have worth and possess rich inner lives one can relate to, is sadly missing from Rent. Multidimensional characters are truncated to profoundly flawed lifeless mannequins dressed up in a vague statement about a world filled with inequality and suffering, all the while perfectly avoiding making any notions that might point the finger at the powers that uphold said inequality and suffering. More specifically, Rent refuses to acknowledge the deliberate neglect of the Reagan administration in its response to the aids epidemic and instead opts to reject society as a whole rather than holding those in power accountable. This is but a dishonest representation of the thousands of queer activists who gave their absolutely everything to convince people that the gays are actual human beings who don’t deserve to die. Furthermore, Rent sets a worrying precedent for how we perceive our potential as active agents in this world.

Rent forces two wildly different stories onto one stage and almost miraculously ends up portraying something very true to life: privileged people appropriating the oppression of marginalised peoples to feel better about their own privileges and justify their lack of action. Now, I know what you’re thinking, and yes, you heard me right. I am going there.

We’ve all seen it. We’ve all felt it. We’ve all done it.

Especially now when civil society is under attack from all angles under this right-wing government, tensions are extremely high and constructive collective action doesn’t seem to amount to anything. People are bound to get disappointed and want to dissociate themselves from the system that in so many ways works to actively harm them.

But since doing nothing is not allowed, we resort to looking the part and inhabiting activism as this role or aesthetic. And when we invest all our energy and what is left of our hope into wearing this façade of action, we start to expect the same from others.

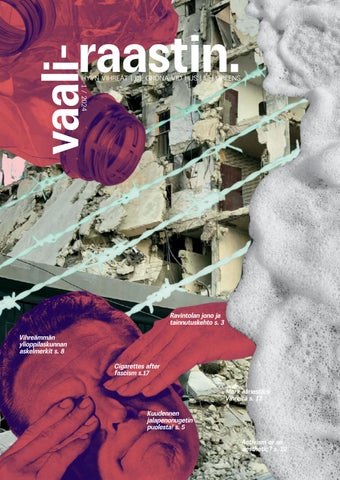

We’ve all seen this drastic increase in acknowledgment of ongoing issues, but what I see as lacking, is action that stems from said acknowledgment. Systems of oppression are widely recognised and various symbols of objection to those systems have been adopted by the masses but sadly little is expected of those carrying those symbols. During the present year, the ongoing genocide of Palestinians has once again appeared in world news. Awareness of the ongoing conflict and its history is ever more present, but acknowledging it has become this good in itself rather than as a means to impart change. And with this I have an issue.

The plight of Palestinians living and, in inhumane numbers, dying under a brutal apartheid occupation that has been funded and legitimized by western powers for decades isn’t a cute pin or a catchphrase to tack on the end of whatever it is one’s doing, but rather a complicated historical and political question that demands to be given more than few words in passing.

To state out loud, I fear that the aesthetification of activism and various other causes works against us. Paired with the panopticonesque hellscape that is modern social media and communities largely shaped by it, the need to wear our others’ suffering as an identity marker has become both a survival strategy and a form of a show trial to differentiate us from them and polish our own image.

Rent is a musical built to reinforce worldviews and acts as a powerful metaphor for how we reinforce our worldviews and fight the cognitive dissonance stemming from our own privileges and the inhumane horros of the world. As such, it is a tragic example of choosing our own comfort over meaningful action. I don’t think much of it, but I am constantly serving it. As a community, we need to find a way to impart social change in our circles and spread awareness without resorting to appropriating the oppression of those whose liberation we care deeply about.