4 minute read

FUNDING HOPE

SebastianStrong Foundation gears up for Keys kayaking trek against childhood cancers

“You beat cancer by how you live, why you live, and in the manner in which you live.” - Stuart

Scott

On May 16-20, a group of 20 kayakers will undertake a grueling 110mile trip from Key Largo to Key West. Their venture is a highly physical battle aimed at combating a parent’s worst nightmare: pediatric cancer.

Meet the intrepid group “Kayaking the Keys for Hope” on behalf of the SebastianStrong Foundation.

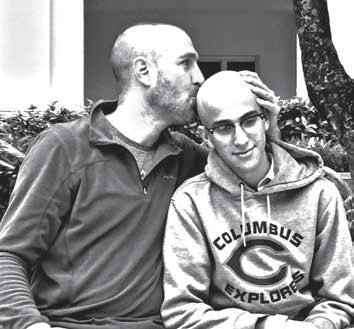

Born and raised in Miami, Sebastian Nicolas Ortiz was only 15 years old when he was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare soft tissue cancer. After a 14-month battle that included four surgeries, 32 rounds of chemotherapy and 23 rounds of radiation, he passed away on Dec. 29, 2016.

Today, the foundation established in his honor by his father Oscar directs funding to bolster cutting-edge research for targeted, less toxic treatments of rare pediatric cancers that may not always earn a mainstream spotlight – and the corresponding research funding – with higher patient numbers.

“What we learned was that Sebastian’s only treatment option was over 40 years old,” Oscar told the Weekly. “As much as we talk about innovation in science, pediatric cancer has been left behind, by and large. It’s a result of, and I don’t say this cynically, not enough kids get cancer, so there hasn’t been innovation in that space.

“Really what we serve as is seed capital for ideas that otherwise won’t get off the ground, because there’s not a return on investment.”

Together with a medical board that advises the foundation of the viability of certain projects, SebastianStrong has committed more than $4 million since its inception in 2017 to research at institutions including Yale, the University of Colorado, Albert Einstein Medical College, Johns Hopkins and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The majority of the group’s donations flow through its annual Discovery Science Award. In 2022, SebastianStrong awarded $672,000 – its largest single award so far – to Children’s National Hospital for a project aiming to use ultrasound technology to deliver targeted, localized medications through the blood brain barrier as a therapy for brain tumors.

“For me, the core of it was, how do we create more options for hope?” Ortiz said. “They aren’t all going to be home runs, but they’re funding a chance, and that’s all any parent (in that situation) wants.”

The kayakers’ upcoming five-day journey is a nod to the physical and emotional toll cancer takes on families undergoing treatment.

“For me, there’s a beautiful symbolism between the water, going through the Keys and paddling to honor someone,” said Kelsey Weaver, a SebastianStrong board member and Marathon resident.

Though an understandably limited group will take up the mantle of the full journey – with others, including Weaver, joining for specific portions – the foundation has invited four families affected by childhood cancer, including some survivors, to paddle the final mile in Key West with the crew.

Keys residents who would like to support the paddlers on their journey can join the team for a happy hour at Marathon’s Keys Fisheries on Thursday, May 18 around 6 p.m. (subject to paddling delays) or cheer them on at their final landing at the Stock Island Yacht Club on Saturday, May 20 at 1:30 p.m.

“We can’t wait to host this group,” said Keys Fisheries bartender Rachel Bowman. “Anything we can do to help support those who give hope to others, we absolutely want to be a part of it.”

To learn more about SebastianStrong and support the nonprofit foundation with a donation, visit sebastianstrong.org.

Mark Hedden

... is a photographer, writer, and semi-professional birdwatcher. He has lived in Key West for more than 25 years and may no longer be employable in the real world. He is also executive director of the Florida Keys Audubon Society.

In a certain way, owning a decent camera with a long lens has ruined birding for me. Or at least ruined things that previously would have suffused me with satisfaction.

I remember, years ago, the first time I saw a Swainson’s warbler, a small, brown, skulky bird that spends its days flipping over leaves with all the grace of a tai chi master. I mean, a Swainson’s can be five feet away and throwing leaves like Jason Statham throwing tables in a bar fight, but it will do it with such subtle and supple moves you could be staring right at it and not even notice it happening.

The first time I saw a Swainson’s warbler was at Indigenous Park. Someone had clued me in on a bush where one might be. And I sat on the ground in the damp mud, stared into the leaf litter and waited for something to move. I sat so long my legs started to go numb. But after 40 minutes or so, the Swainson’s made an appearance. It came out from behind one section of impenetrable thicket, walked slowly across two or three feet of relatively open space, and disappeared behind another section of impenetrable thicket. It was a 15- or 20-second look, but it was enough. I felt as if I’d seen the bird, caught all the field marks that distinguished it as a Swainson’s warbler – the overall drabness, the pointy triangularity of the head, the warm ruddiness of its cap – and had enough time to let it all sink into my brain.

I grooved on it for days. And for a long time, that type of experience was enough. I’d seen the bird, I’d understood what it was, I’d expanded my world.

Then I got a camera.

Cameras are great because they’re time machines of a sort. They won’t bring you back in time, but they will let you pause it, hold on to a moment, walk around in it as much as the frame will allow, keep it. In the practical sense, if you see a bird and don’t know what it is, you can figure it out later. And in the modern era of birding, if you see a rare bird, a lot of times it won’t be accepted as a record unless you can produce a photo.

Also, for some reason, if I take a photo, I have an easier time studying it and seeing new things, as opposed to looking at someone else’s photo. I think it has something to do with being connected to the moment the shutter snapped.

Those moments, though, are hard to come by. One of the first things you learn when you start down the road of wildlife photography is