8 minute read

CATCHING UP WITH KYLE

CATCHING UP WITH KYLE BY: MARION RAWSON

LONG DISTANCE INTERVIEWS HAVE BECOME THE NORM THESE DAYS, SO IT IS NOT SURPRISING THAT THAT IS HOW I CAUGHT UP WITH KYLE BLAIR RECENTLY. WHAT MAY BE SURPRISING IS WHAT HE HAS BEEN WORKING ON!

Advertisement

M: WHAT HAVE YOU BEEN DOING FOR THE PAST YEAR AND A BIT?

K: Needless to say, the past fourteen months have been unlike any other. Some of what I try to bring to my acting has suddenly become critical to practice in my daily life: simply trying to be in the moment without getting caught in thinking too far ahead. The Shaw’s resilience in the face of these challenges has been astounding. Just over a year ago we moved our 2020 rehearsals to Zoom. Then through the summer Ryan deSouza and I produced a series called “Gift of Song” where members of the ensemble recorded musical offerings which were delivered to over 50 individuals as well as long-term care homes in the Niagara community. I ended 2020 performing in The Shaw concert series. In the midst of this, not knowing if we’d be able to continue our Shaw work, I decided to start a Master’s degree which I am still engaged with. It has been, unbelievably, a year of satisfying and challenging work for which I am hugely grateful.

M: WHAT WAS IT LIKE TO REHEARSE AND PERFORM DURING A PANDEMIC?

K: The concerts were a special moment in time for a few reasons. We were all very aware that we were coming together for the first time since the start of the pandemic, and also in the context of the renewed and vital Black Lives Matter movement. We were exploring how to proceed in both a safe and more inclusive manner. It was complicated, difficult, and joyous. It was not always comfortable, but we collectively leaned in. I will always be grateful to The Shaw for making space for this and for the camaraderie and leadership of Kimberley Rampersad, Paul Sportelli, Ryan deSouza, Meredith Macdonald, Olivia Sinclair-Brisbane, Élodie Gillet, Alexis Gordon, Kristi Frank, Jonathan Tan, Andrew Broderick, and James Daly.

The concert series reaffirmed for me the value of TC’s [Artistic Director Tim Carroll] “two-way theatre”. I originally understood this concept to mean that a story is created in the space between actor and audience. However, I was humbled and moved to see that this exchange transcends what we do on the stage. We started those concerts in people’s backyards. There we were, seeing each other in the light of day, all struggling through a difficult time, and trying our best to hold on. It became clear to me that the core of The Shaw experience is in the reciprocity between artist and audience. I am certain that we got as much out of those performances as our audiences did. It drove home for me how Shaw is in, and of, many communities and that we all benefit from coming together.

M: WHAT PROMPTED YOU TO GET A MASTER’S DEGREE AND WHAT IS YOUR DEGREE IN?

K: Pursuing an MA had always been at the back of my mind, but the timing had never felt right. With all the uncertainty around the pandemic, it felt like a productive thing to do to keep myself focused. I’m working toward an MA in Theatre Studies at the University of Guelph. It has been illuminating to look at what we do as practitioners from an academic perspective. Guelph was attractive to me as they have some exceptional artists on faculty (Dionne Brand, Lawrence Hill, and Judith Thompson among them), but also because The Shaw’s archives are housed at Guelph. I am interested in examining Shaw’s history because I have become aware that there are a number of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour) artists that have been largely forgotten or erased from Shaw’s past.

M: CAN YOU TELL US MORE ABOUT YOUR RESEARCH?

K: As we look ahead with the desire to build an equitable future, I believe that we must also look back and reexamine our past. Many of The Shaw’s histories—as produced by the photo display in the George bar, the poster hallway backstage at the Festival, and in L.W. Conolly’s The Shaw Festival: The First Fifty Years—document predominantly white narratives. While this is largely reflective of the makeup of the company in years past, many BIPOC individuals are overlooked by this generalization. To his credit, Conolly states in his book: “I hope and expect that in the fullness of time there will be other histories of the Festival.” I interpret this to mean not only “future histories” to come, but also “past histories” which have gone unexplored. The goal of this research is to give a platform to Shaw’s underrepresented artists and to avoid (further) erasure of BIPOC artists who have made valuable contributions to the Festival as early as 1963. Following archivist Lae’l Hughes-Watkins, I think of this as “social justice through archival repair.”

M: HOW FAR BACK IN TIME DID YOUR RESEARCH TAKE YOU?

K: My research took me to place, more than time. I began this inquiry by performing physical searches of Shaw buildings. I discovered that by virtue of reorganization, staff changes, and renovations, various documents and even some spaces had been largely forgotten. (My favourite example of this is a tiny room at the Festival which used to function as a stage management booth over a rehearsal studio which now serves as the Design offices. The booth window has been dry walled over but the cubby behind still exists. If you are missing a pair of downhill skis circa the 1990s, they are still there.) To date, my searches of the Festival and Royal George theatres, the prop shop, and the warehouse have uncovered forgotten photographic evidence of 11 BIPOC artists who appeared in productions at The Shaw between the years of 1963 and 1998.

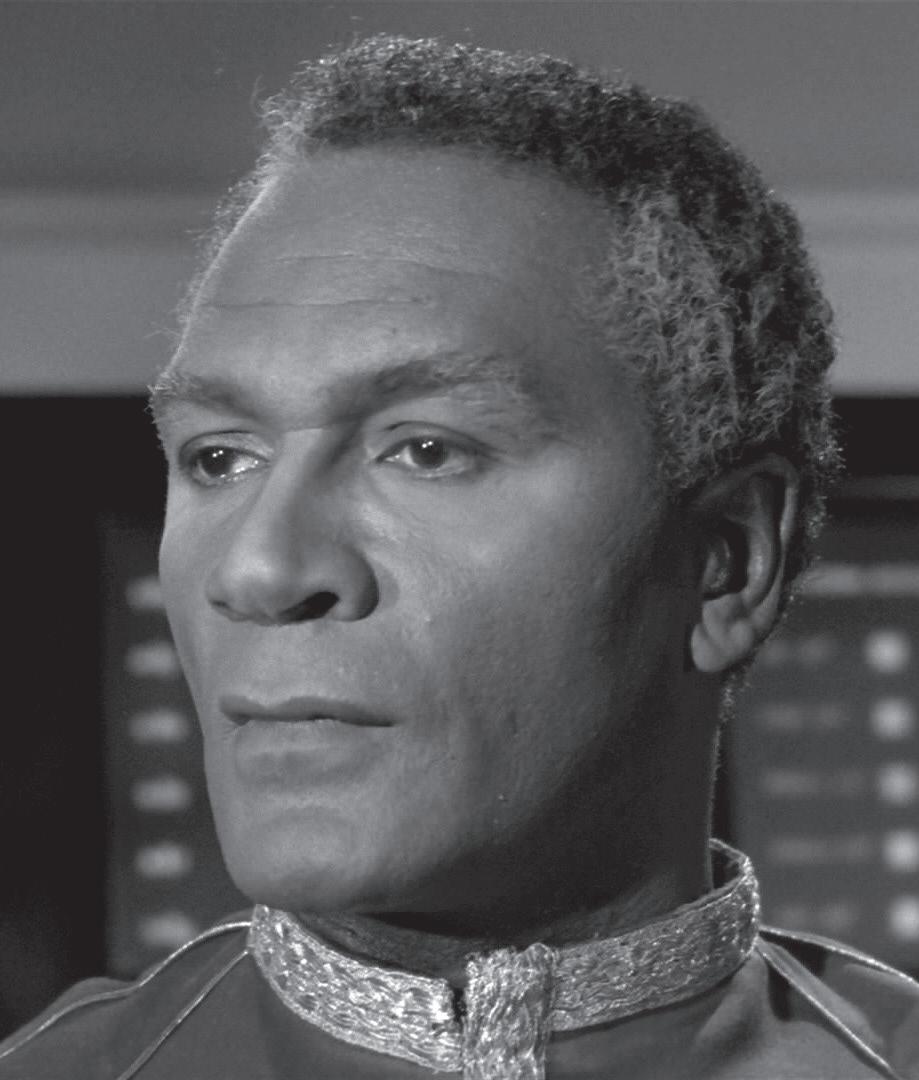

These artists, in order of their Shaw debuts, are: Percy Rodriguez (1963), Leonard Chow (1983), Michelyn Emelle (1984), Debra Benjamin (1989), Cassel Miles (1992), Catherine Bruhier (1992), Nigel Shawn Williams (1996), Brenda Kamino (1996), Janet Lo (1996), D. Garnett Harding (1998), and Camille James (1998).

M: WAS THERE ANYTHING THAT SURPRISED YOU?

K: The photo of Percy Rodriguez was a discovery that really excited me. Rodriguez appeared to rave reviews in 1963 (The Shaw’s second season), and again in 1966. A Black actor from Montreal, he went on to have an astounding career breaking down race barriers by playing an officer of authority on Star Trek and a neurosurgeon on the soap opera Peyton Place. (You can still hear his voice in the trailer for the film Jaws.) Most of these “found” artists were not included in the various archival installations throughout the theatres. We are remedying that. Jenniffer Anand (Communications Coordinator), as well as Ensemble members Marla McLean, Kiera Sangster, and I are working to augment what is currently displayed. We have been combing through the digital archives in order to represent the Ensemble in the fullest way we can. These displays are important as they communicate—to audiences and artists alike— who belongs in these spaces. Of course, we want these spaces to belong to everyone.

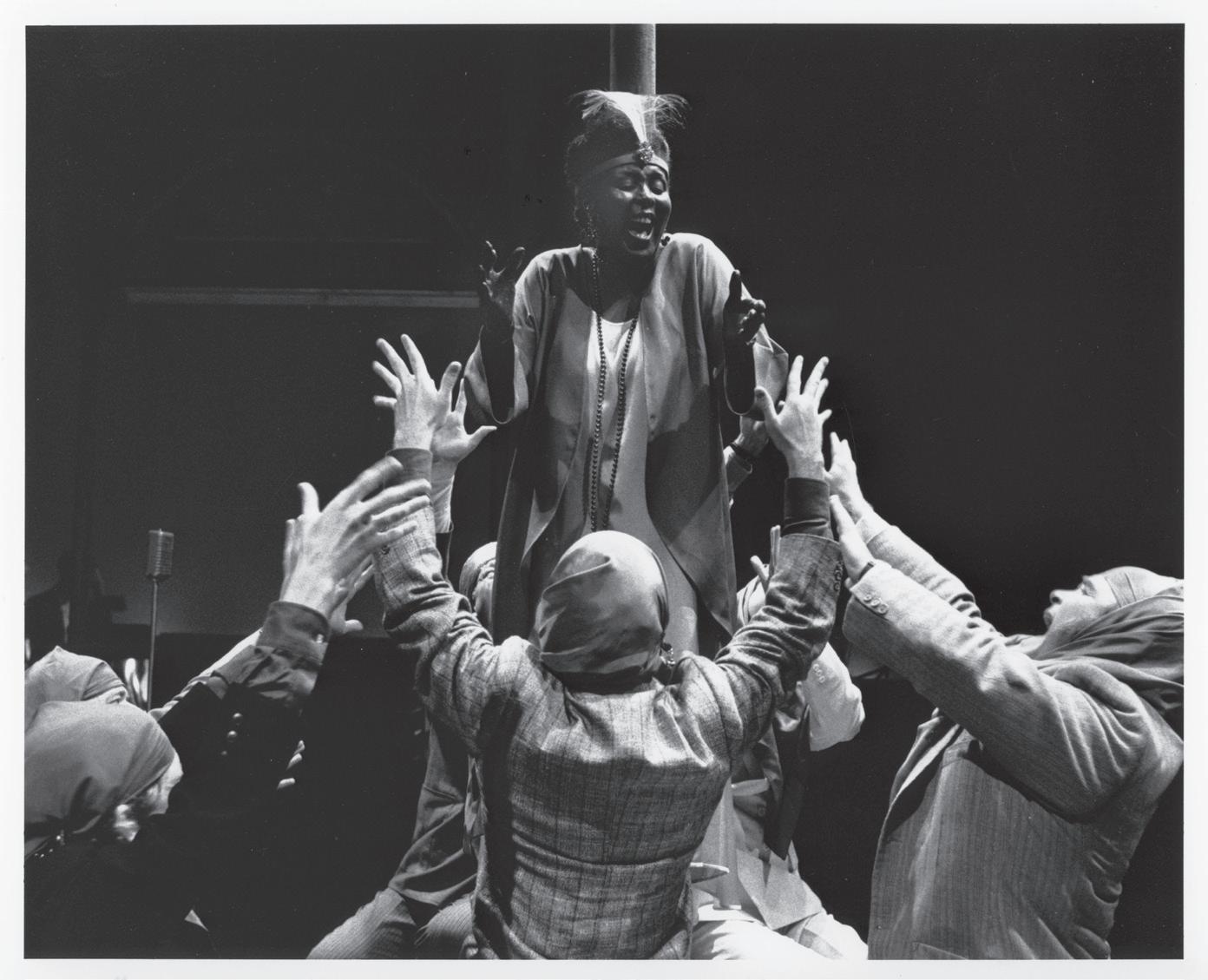

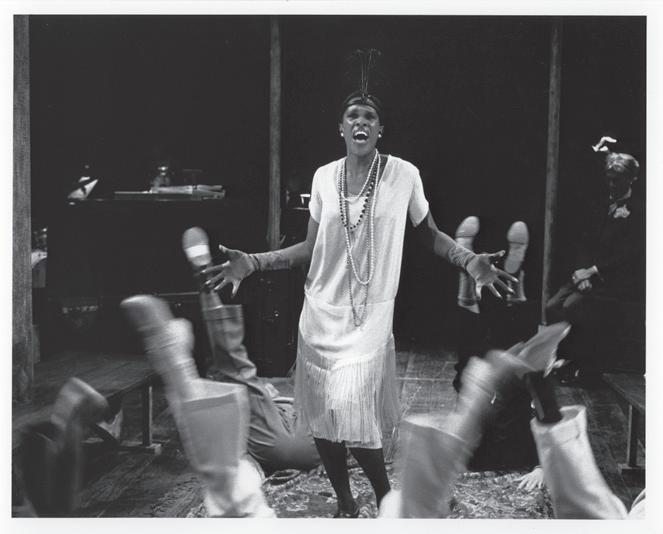

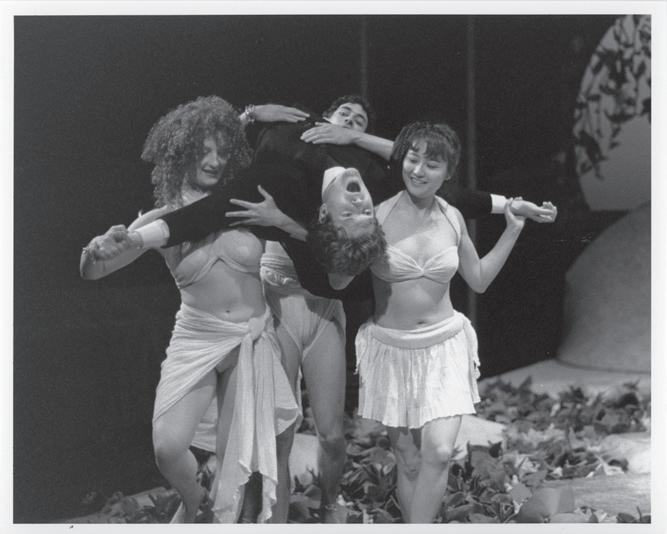

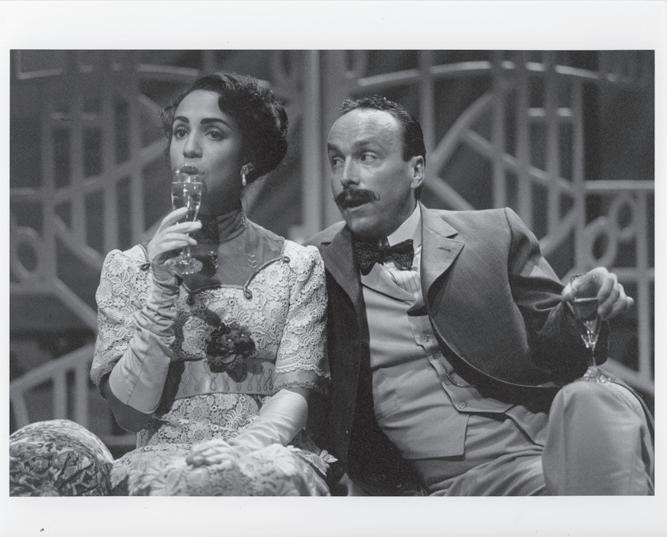

This page, from top: Text from original photo, taken from The Performing Arts in Canada, Winter-Spring edition of 1964: “Percy Rodriguez as the mighty Ferrovius, Andrew Allan as the effete Caesar (perhaps Claudius) in Androcles and the Lion”; Percy Rodriguez as Commodore Stone in Star Trek (1967). Next page, clockwise from top: Leonard Chow (1983); Michelyn Emelle in Roberta (1984); Catherine Bruhier with Mary Haney in Overruled (1992); Rosalind Keene and gentlemen of the Nymph Errant ensemble (1990); Catherine Bruhier with Peter Hutt in Overruled (1992); Neil Barclay and Camille James in Village Wooing (1999); Lisa Waines, Shaun Phillips and Janet Lo give Ben Carlson a warm welcome in The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles (1996); Debra Benjamin in Nymph Errant (1989); Photos on opposite page by David Cooper.

M: DO YOU SEE A BROADER APPLICATION OF WHAT YOU HAVE LEARNED BEYOND YOUR MASTER’S DEGREE?

K: While (I hope!) my acting career isn’t over yet, I’m interested in continuing a relationship with The Shaw’s history. I had first visited the archives at Guelph before rehearsing our 2019 production of Man and Superman. (It’s an intimidating play, and I thought it would be helpful to see how other directors and actors had approached it.) The archive is an astounding resource, but I was worried by what I encountered there. The production recordings are still on VHS tapes, which are obviously deteriorating.

Although beyond the scope of my MA work, I hope to someday contribute to the preserving of The Shaw fonds. I’d also love to see the archives become more accessible for artists, students, community members, and other visitors to The Shaw. It’s a unique and important collection.

M: WHAT DOES “FONDS” MEAN?

K: “Fonds” is an archival term which means a collection of documents from one institution. It is a new word for me as well!

M: HOW DO YOU THINK THIS UNDERSTANDING ABOUT THE SHAW’S PAST WILL INFORM YOUR FUTURE? EITHER AT THE SHAW OR ELSEWHERE?

K: This research has reinforced that there is never just one way of looking at history, just as there is not one way of doing a play. I’m trying to practice that in my own thinking these days: being willing to sit in contradictions and complications.

M: WHAT’S COMING UP NEXT FOR YOU?

K: I plan to finish my MA work by the end of the summer, and I have my fingers crossed that I’ll be on a Shaw stage again soon!