35 minute read

Oblates

KANSAS MONKS Oblates

Abbot provides ‘tools’ for a good Lent

Each Lent Abbot Barnabas selects a book for all the monks to read during Lent. We then meet every Tuesday evening to discuss certain chapters of the book. One of the monks, a volunteer, leads the discussion.

This Lent the Abbot selected Mark Braaten’s book, Prayer as Joy, Prayer as Struggle. In 11 short chapters the Rev. Braaten truly brought various aspects of prayer to life. Each chapter is entitled with some phase of what prayer might be at any given time for each person. Some of the titles of the chapters might whet your appetite to buy the book—“Prayer as Thanksgiving,” “Prayer as Request,” “Prayer as Hope,” “Prayer as Listening.” Mark Braaten is the senior pastor of Our Savior’s Lutheran Church in Tyler, Tex., and you can buy his book at a book store or directly from Liturgical Press in Collegville, Minn., at its Web site, www.litpress. org. I especially relished the Chapter on “Prayer as Listening.” I have been reflecting on the various prayers that are proper to each celebration of Mass Brother Martin Burkhard such as “Opening Prayer,” “Prayer over the Gifts” and “Prayer after Communion.” I would like to take some examples from the prayer after Communion and the strong challenge leveled by that prayer. At the end of every Mass we are directed to go on our way and live out what we have just celebrated. It is so easy to sit back and think that something is over and we now return to our everyday life. On the contrary, what we celebrate in daily or Sunday Mass must become a reality in our lives of faith. What first struck me in one of the prayers after Communion was the phrase “May we become what we have received.” In some way or other I have tried to recall this at the end of every Mass since that time.

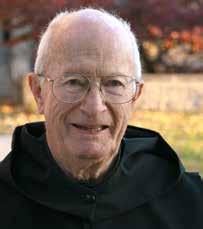

When we truly listen we hear things that may well change our way of thinking and acting. Some other phrases that offer challenges follow: “Help us to live by your words”; “May these mysteries give us a new purpose”; “May the new life given us increase our love and keep us in the joy of your kingdom”; “May your celebration have an effect in our lives”; “By these mysteries help our faith grow to maturity.” It seems to me that any Brother John Peto one of the above challenges us Director of Oblates greatly as Christians.

I firmly believe that our faith will only become real when we find it a daily challenge.

Each of us is offered many opportunities throughout the day to become more alive in our great love of Jesus.

I would like to add a couple of notes about oblates. This message in each issue of Kansas Monks is my principal way of keeping in contact with the many oblates of the abbey. The high cost of postage prohibits sending a separate newsletter to every oblate. I do however send a short note to those oblates who try to attend meetings on a regular basis. If you would like to be added to that list please let me know.

The biannual convention for oblate directors and two oblates from each oblate community will be held at St. Vincent Archabbey in Latrobe, Penn., from June 26 to July 1. At this meeting there will be an election for Prayer as Joy, Prayer as Struggle by Mark President and Vice Braaten is available from Amazon.com for $10.16 President of NAABOD (the National Association of Oblate Directors). I have served as Vice President for the past four years and will not be running for office. Please pray that we will elect officers who will serve well the men and women living the Oblate way of life.

- Have you ever considered becoming an Oblate of St. Benedict? - Does it mean I make vows? Do I have more prayers to say? Does it cost money? - Do I have to make radical life changes? Come and see or contact me, Br. John Peto, jpeto@kansasmonks.org 913-360-7896

Wordin a

The following homily was delivered by Abbot Barnabas Senecal at St. Benedict’s Abbey Church on the second anniversary of the dedication of the Abbey church, April 29, 2009

A Community Built from Stones

“Believe me, woman, the hour is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem.”

Jesus must have confused people with that statement. Jews had such reverence for Jerusalem as their sign of favor from God, where their “chosen-ness” was affirmed. Many regarded mountaintops as places where God dwelt and could be honored in sacrifice.

We reflect on Jesus’ statement, conscious that we do cling to place, especially as Benedictines. We live within that place, pray there often, and bury our brothers from this place when life ends. And yet, we know that more important than place is a spirit that gives us life day to day, wherever we are assigned to work. We know the truth of our lives from within the context of community. That community has stones on which it is built, stones that are foundations, stones that are capstones, stones that are not visible and stones that are visible. Literally, this church in which we gather was built on earlier stones. The foundation stones at this end of the church were laid in 1929. New stones were placed upon them in 1957. The old stones were quarried right here in Atchison; the new stones came from Minnesota.

Some of the invisible stones on which this community was built were monks.

They were German-born, men who had come to St. Vincent Abbey in Pennsylvania; they volunteered or were assigned to come to “the Sahara,” namely, to Kansas.

The first monk to die here was Brother Bernard Ball, born in Catowa, Illinois; he was 27 when he died on April 25, 1882. Two hundred twenty-seven other monks have been buried, invisible to SUMMER 2009 us who inherit their many contributions, who share their spirit and live in their truth. Our first abbots, foundation stones as it were, came from families that had come to the United States and found the Benedictines in various ways. The first Abbot Barnabas Senecal abbot, Innocent Wolf, was born in Cologne, Germany, and moved with his family to Wisconsin; from there he joined St. Vincent in Pennsylvania. He was elected our first abbot in 1876. Our second abbot, Martin Veth, was a native of Bavaria whose impoverished family had moved to Atchison in 1884 from New York. Our third abbot was born in Ireland and came to this country as an orphan, living in Kansas City.

We celebrate today the dedication of this church in 2007, the year of our 150th anniversary. That ceremony was not done in 1957 for various reasons.

It is now done, and we happily observe its anniversary. This is a place of prayer, private and public. It is a place where the spirit is touched and the spirit is shared. That is the truth in which we prosper.

We gather living stones from many places to continue this community’s life.

We are diverse and yet we have much in common. May we not be strangers but fellow citizens. May Christ be our capstone and our foundation, he being visible to us and at once hidden, giving support and guidance through the Spirit.

The original Abbey cornerstone

Prayers of the Faithful

- For all who contributed funds to build our monastery and our monastic church, to be places that survive on sure foundations, - For all who have contributed their talents as members of our community, keeping it strong and giving support to many, - For all who have encouraged others in their lives of faith, sharing their spirit and their truth, - For all who come to this mountain top, this new Jerusalem, that they may find it to be a place where the Spirit lives,

God is everywhere. Even in prison.

Father Bruce Swift found this out the day he met Big Jim.

The prisoners at Fort Leavenworth didn’t trust anybody. Father Bruce was there for the ‘Residents Encounter Christ’ Retreat in the 1980s.

“Before we left,” Father Bruce said. “they were hugging people.”

Swift describes Big Jim as a “big, muscular guy” who introduced himself by describing how he got the nickname, aside from his stature.

“They call me Big Jim,” he said, “because when I yell down the hallway, it gets quiet.” And things got quiet with that introduction, but the silence would soon speak volumes.

At the end of the weekend-long retreat, the prisoners shared their feelings aloud. Guess who spoke up first.

“They still call me Big Jim,” he said, “but it’s because I have a big heart now.”

Father Bruce has been doing prison ministry ever since.

“…I was in prison and you came to me.” –Matthew 25:36

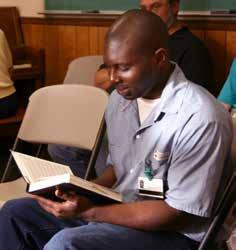

Robert Washington has been behind bars at the Lansing Correctional Facility for two years. He signed up for the Catholic callout about six months in.

“I’m trying and I’m progressing every day to be a better person,” said Washington. “This group has really helped me.”

Washington finds peace in the weekly Bible study group.

“It’s always a difference when you can study and read with someone else,” Washington said. “Just a different air than sitting in your cell reading.”

He’s eight years away from getting out of that cell, but Washington already has plans.

“I’m studying business now, I’m back into writing poetry,” he said. “It’s just constant growth.”

That growth, he says, starts with the positive interaction he has with this group each week.

“Find something good that you love doing,” he said. “Stick with it and grow.”

He hopes to one day start a business with the poetry he writes.

Prison is the last place anyone would expect to find freedom. But Derek Coe may never have felt so free.

“God has a reason for everything,” Coe said. “The reason I’m in prison is to slow down and actually think about things in my life before I go back out.” 14

Father Bruce on his way out of the maximum security section of Lansing Correctional Facility.

Coe tries to use his time wisely, studying German, Spanish and American Sign Language in preparation for a hopeful career as an interpreter when he gets out of prison this November. In the meantime, he stays focused—from the inside out—on his goals.

“I want to make wiser, smarter decisions,” he said. “I pray all the time in my room for God to give me wisdom and intelligence and good guidance to light the path of my choices in the future.”

For now, the 24-yearold, two-time inmate who converted to Catholicism inside a prison takes what he can from the fellowship.

“There’s a lot of mentorship that can help me out through the week,” said Coe. “There’s a lot of people’s insight about what they have to say about Bible verses.”

As Coe and his peers prepare to branch out, they continue their connection to the vine.

Scott Reaka isn’t usually a man of many words, but when the request for a reader was called out at Bible study— his hand went up first. “Something told me to read it,” he said. “I feel the Spirit in me to read the Bible.” A self-professed shortcutseeker, Reaka has been in prison for burglary before, and he’s there again. “The devil is always trying to throw stuff out,” said Reaka. “People always take the bait easy.” Raised Catholic, the

German-born Reaka tried to go to church every day when he was on the outside. Now, church comes to him. And that’s good news for someone who says he tends to “go back to his old ways.” Despite that tendency, Reaka says the “hard work” of “going straight” is much easier with the support he gets every week.

It’s hard to match an educational experience like prison ministry. Father Bruce takes two or three Benedictine College students along to Lansing every year.

Passing through electronically locked doors, seeing the razor wire and the mere thought of being inside the walls of a prison can intimidate almost anyone.

“They don’t know what the prisoners are in there for,” Father Bruce said.

Aaron Rains was nervous at first, but his outlook changed after just one evening.

“Those guys need someone to come in and talk to them,” Rains told Father Bruce. “They are just normal

people who made some bad choices.”

“Jailhouse confession” takes on a new meaning when Father Bruce visits the prisoners.

“It’s a good feeling to see these people who have made some mistakes wanting to straighten out their lives,” Father Bruce said. “They’ve learned their lesson and they’re going to change.”

Change is a powerful word these days. Even a seemingly simple change—like a change of clothes—can change the day’s outcome.

Just ask Aaron Rains.

This particular trip was far removed from his first visit to Lansing. The aforementioned intimidation was all but gone. In fact, Rains had grown so comfortable with the prison visits that he almost left the Benedictine campus dressed in a light blue shirt and blue jeans. Just like the prisoners.

Father Bruce noticed Rains’ wardrobe malfunction in time and he was allowed to leave the prison that Wednesday evening.

Participating prisoners enjoy the routine: Bible study and Confession on Wednesday, Mass on Saturday. The combination of regularity and formality is comforting.

But sometimes, the simplest things make all the difference. Being treated differently—like more than just a prisoner—allows them to talk, to feel more human.

“I do not, in any circumstances, blame them for what they did, I don’t make any accusations, I don’t tell them how bad they were,” Father Bruce said. “I just listen to them more than anything else.”

“Listen…”—the first word of the Rule of St. Benedict

Father Louis Kirby has literally worn his fingers down in prison ministry.

“Turns out when you get old they can’t get a fingerprint off of you anymore,” he says with a grin. “When I found that out I told [prison officials] I was going to get a new job—robbing banks.”

Father Louis won’t be taking up new employment, but at 86 years old, he has decided to end his 15 years of work behind prison walls. When he had to ask some inmates at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary to help him up to the altar at a Mass earlier this year and later took a spill on the prison stairs he realized his time had come to hand over the vestments to another monk. Father Louis will no longer be visiting Leavenworth two Sundays each month, “one to the Prison Farm and one to the Big House” as he puts it. The whippersnapper who will be succeeding him is 78-year-old retired Abbot Owen Purcell. However, Father Louis’ Prison Ministry won’t end completely, thanks to seeds he has planted in the last decade and a half.

Father Louis began prison ministry when he was at the now closed Holy Cross Abbey in Cañon City, Colo., which was in Fremont County, home to 14 prisons. In the early days, one prisoner asked to be an Oblate of the Order of St. Benedict and Father Louis obliged. The Oblates served by Father Louis grew in number as word spread. “The first thing I knew we had a little group of Oblates,” he recalls. A volunteer took over the group around Cañon City.

“Prisoners move,” Father Louis says. “They take their ideas with them.”

So did Father Louis. His Abbey closed and he moved to St. Benedict’s Abbey in Atchison, Kan. He took his Oblate file with him.

Now, St. Benedict’s has about 70 oblates in 10 to 12 prisons around the country. There are oblates in prisons in North Carolina, in Illinois, and in Pocahontas, Va. There are oblates in six prisons in Colorado, in Arkansas, and at Leavenworth. There are Oblates at five prisons in Texas. “I don’t know much about prisons in Texas,” Father Louis says, “but there are a lot of them.”

Father Louis keeps in touch with the Oblates with a newsletter that he sends out four to five times a year that includes lessons on the Rule of St. Benedict and other holy reading, and occasionally he shares a letter from an inmate:

“It is nice to receive your Oblate newsletter and the Kansas Monks. I always find at least one spiritual message that inspires me even more so in a prison setting,” one imprisoned Oblate wrote. “We have to take one day at a time or we will spend an inordinate amount of time on things that can’t change. The past and the future need to stay just where they are—in the past and in the future. The most important thing I do is to live one day at a time and start each day with the Divine Office.”

“These are human beings,” Father Louis says. “They need spirituality. Many of them didn’t get much on the outside.” Father Louis says many of the prisoners he has met are good people, “sincere people who want to evolve spiritually.”

Father Louis receives many letters, and he will continue to visit their authors with his newsletter and with his prayers, planting seeds as he goes.

“The Book of Psalms was daunting and difficult to follow, but knowing that millions of other believers were praying the exact same prayers was somewhat empowering,” wrote one inmate. “It’s more than just the prayers, though. After spending a good portion of my life doing as I pleased, I needed guidance. Wouldn’t you know St. Benedict thought of that also…Through trust in God, with the help of St. Benedict’s Rule I am learning happiness and peace in one of the most unhappy places.”

KANSAS MONKS RULE IS WELLSPRING OF COLLEGE MINISTRY

by Dan Madden

It was in the water in the old days.

The students of St. Benedict’s College used to drink up the Benedictine spirituality almost unconsciously, as if from a Kansas well. “You had monks who were prefects in the dorms, who were professors in the classroom, who were pastors in the chapels,” Father Brendan Rolling notes.

Today, putting the “Benedictine” in Benedictine College is more like visiting a Flint Hills spring. “Today, we are very intentional about weaving the values from the Rule of St. Benedict into the Student Life program,” says Father Brendan, the college’s director of ministry and mission. A fountain for those values is the college ministry program under Father Brendan’s guidance.

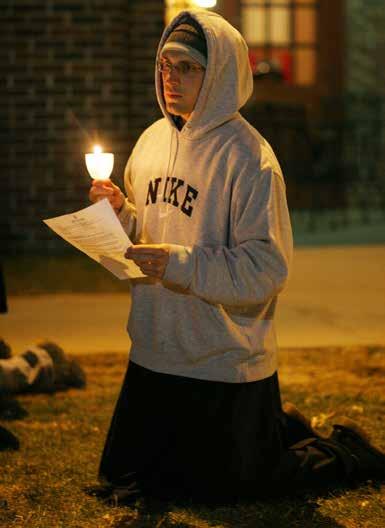

Through the program the monks provide pastoral care, celebrating Mass and the sacraments with the students, and some voluntarily provide individual spiritual direction to students at the Abbey. Father Brendan says it is important to maximize student contact with the Benedictines. He also points to the Partners in Prayer program in which a student can join a sister from Mount St. Scholastica to pray the Liturgy of the Hours and share a meal. Sign-ups climbed more than 69 percent for the program this year.

Benedictine College President Steve Minnis doesn’t hesitate for a moment in declaring his school’s Ministry Office the best in the nation.

The number of activities available in the program, the number of students clamoring to participate, and the quality of preparation those students receive to assume leadership positions in their parishes once they leave Benedictine are “almost staggering,” Minnis says.

The confident president is backed up in his assertions by the Cardinal Newman Society, which has declared Benedictine College one of the 20 best Catholic colleges in the country, and by the dramatic increase in the college’s ministry reach and participation over the past two years.

Recently, Minnis hosted Bishop James V. Johnston Jr., of the Diocese of Springfield-Cape Girardeau who had heard good things about the B.C. ministry efforts and wanted to see for himself. “He came for a tour and was blown away by the faith life on campus,” Minnis says.

President Minnis is equally certain that there is a direct lineage between his school’s 21st century ministry success and the wisdom of a 5th century saint—St. Benedict of Nursia—whose spiritual descendents, the Benedictine monks of St. Benedict’s Abbey and sisters of Mount St. Scholastica Monastery, founded the college and continue to shepherd it today as a primary apostolate.

Father Brendan Rolling, Benedictine College Director of Campus Ministry, is a spiritual resource for Benedictine students.

Sitting outside his Ministry Office in the B.C. Student Union, across a small study area from the basketball coaches’ offices, Father Brendan Rolling, director of ministry and mission, discusses the the program with the Xs-and-O’s air of a coach.

“The goal is to be effective,” he says. He explains that he chose early on to model Benedictine’s program after an athletic department. “They have their head coach, their assistant coaches, their varsity and junior varsity. The goal is optimal participation. We ought to set ourselves up the same way.”

Father Brendan says he didn’t face the same challenges as other campus ministers. Getting students to participate or to attend Mass is not a Benedictine College problem.

“One study I read said that 80 percent of students lose their faith during college,” he said. “At Benedictine, 80 percent of students go to church services on Sunday. The typical kid at Benedictine is an all-star at a Newman Center on another campus.”

The problem that led to a reorganization of the B.C. ministry program was a bottleneck, Father Brendan says. There were simply too many students wanting to participate. The program was spread too thin.

“We’re getting students turning down full-ride scholarships at other schools because they want to be in a Catholic environment,” he says. “They are making faith development a priority. They are bringing their faith to their professional development. And that requires a sacrifice. Anything that requires a sacrifice is going to attract smart, talented and generous students.”

Benedictine’s college ministry is divided into seven teams. Each team is led by three or four students who have completed training in the Benedictine Leadership Seminar, a program based on principles from the Rule of St. Benedict.

Father Brendan says the leaders’ jobs are to “recruit, train and empower” student volunteers. “Each team’s job is to implement the documents of the Church that are relevant to the teams’s mission,” Father Brendan says.

With its wider reach the ministry and mission program has broadened from seven students to 27 this year. One hundred ten students—

thirteen percent of the college’s student body— are now signed up as liturgical ministers. The Rereat Team has gone from four volunteers to 76. Eleven retreats serving 563 teens last year increased to 20 serving 1,105 this year.

In the past decade the college has gone from two praise-andworship choirs to nine who can sing chant, chorale and hymns, and who feature organ, piano and guitar accompaniment. In that time Bible study groups have increased from two to 44. The college has also offered and increased participation in self-funded alternative Spring Break mission trips to El Salvador, Belize, North Dakota Indian Reservations, and a mission of Mother Teresa’s order in Los Angeles. Prior James Albers and Brother Leven Harton led this year’s trip to El Salvador.

“Father Brendan has this ability to see talent in young people,” President Minnis notes. “And they flourish under his leadership.”

Mike Schaad came to Benedictine College a freshman planning to play tight end on the football team, but wound up starting for Father Brendan’s team.

Schaad, who grew up Catholic in a parish with a strong youth program, attended a campus retreat not long after arriving at Benedictine and wasn’t impressed.

“I felt like it was wasting the time and money of the students who were attending,” he recalls. “It was really thrown together. There wasn’t a theme; there were no sacraments, there was no Mass. It was pretty shallow and fun in the sun.”

Schaad approached Father Brendan and voiced his concerns. “I said I think you should fix it, and Father Brendan, as he always does, said, ‘Why don’t you fix it?’”

Schaad stumbled back to his dorm room with a few sleepless nights ahead of him. He hadn’t planned on getting involved in campus ministry, but he couldn’t get Father Brendan’s abrupt challenge out of his head. Schaad had developed his own fence-building business back in his hometown of Dallas, Tex. He thought perhaps, his organizational skills could be put to use in helping Father Brendan’s efforts.

“God kept kicking me,” he says.

Schaad dropped football and accepted the priest’s challenge.

“Father Brendan told me he wanted me to build the most dramatic retreat program in the country,” Schaad says. As coordinator of Set Free Ministries, Schaad and his volunteers in the past two years have expanded the retreat program for high school and confirmation students in the four-state region of Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas (MINK) from 260 students In the next issue: Part II of our look at the Benedictine College apostolate of St. Benedict’s Abbey: Sacramental ministry and spiritual direction. the year before last to more than 1,100 students this year.

“We’re getting there,” Schaad says with a smile.

This year he will turn the program over to trusted volunteers as he moves on to his next challenge, an assistant football coach position and resident assistant at Maur Hill-Mount Academy. “It’s time to get a new group in and see what they can do,” he says.

Sarah Daszczuk, a junior theology and youth ministry major, says that while Benedictine enjoys a strong Catholic environment, the ministry teams are not resting.

“A lot of students already go to Sunday Mass, but now we need to take that to the next level of giving our lives to Christ,” she says. “We need to make sure we don’t get complacent.”

In that quest, she says, the Benedictines are good role models.

“The students love the monks, they want to see them,” she says. “We are a community that lives together and works together; we share our joys and struggles together. The most important thing to do together is pray. I consider this campus my home, and having the monks here is the perfect model of community for us.”

For Schaad, the availability of the Abbey is “unbelievable.”

“You can go up and hunt a monk down anytime you need someone to talk to,” he says. “They don’t just live on campus, they are part of campus. It’s a good witness of what a real man should be like.”

President Minnis concurs, both as an alumnus and as an administrator looking to the future of his institution.

He says it was under Father Brendan’s guidance that the school wrote the school’s Mission, Vision and Values, to clarify the college’s Benedictine spirit. The Values, which are each based on a passage from the Rule, are: Jesus Christ, Community, Conversion of Life, Love of Learning, Listening, Excellence Through Virtue, Hospitality, Stability, Stewardship, and Pray and Work (Ora et Labora).

“The Rule of St. Benedict is the oldest living organizational tool in the world,” he says. “Our values are inspired by it. The Benedictines are a great example to our students on how to live out their faith.”

Minnis notes that 50 years ago the average student at St. Benedict’s College would have gone through elementary school, high

KANSAS MONKS school and college with fewer than five teachers who were not from a religious order. Today’s Benedictine College student may go through the same levels of education and have only one religious teacher.

“It is important for us to take advantage of the religious we have and get them in front of the students,” Minnis says. “It is important that we promote vocations and help sustain that legacy here in Atchison. And finally, it is important that lay people understand what it means to be Benedictine and revel in this rich tradition that has been handed down through the generations.”

Perhap Daszczuk summed it up best.

If it weren’t for the monks and sisters, “Benedictine would just be a name instead of who we are.” 1. Place of Christ – teach according to His instruction

2. The leader is responsible for the flock yielding no profit

3. Lead by example more than words, and give the commandments to receptive disciples with words

4. Avoid all favoritism (show equal love)

5. Change the ranks of others as you see fit, as justice demands

6. Lead others according to where they are in the journey a. Use argument – with the undisciplined and restless b. Use appeal (to greater virtue) – with the obedient and docile c. Use reproof and rebuke– for the negligent and disdainful (cut out the sins while you can)

7. More is expected from whom more has been entrusted

8. Keep the flock from dwindling, rejoice when it increases

9. Do not show too great a concern for the fleeting, temporal things. Rather seek first the Kingdom of God

10. No excuses.

Adapted from Chapter 2 of the Rule of St. Benedict

Flying God’s Friendly Skies

a letter to the editor

Your article “Why we need Benedictines” was great and so informative (Spring 2009). Coincidentally, I had the day before received the Rule of St. Benedict from Roman Catholic Books in Fort Collins, Colo.

In the accompanying article “The Vow of Conversion” Father Louis Kirby was quoted, “Everybody has to keep working to be better, to keep reforming their morals. The only difference is we do it as a vow. I guess that should help me get on the beam.”

His statement, “get on the beam,” turned me on. That is the key to success whether the vocation is as a priest or a pilot or a farmer or a janitor or an editor. The success is in how the beam is used. I have carried that axiom around in my head since I was 19 years old.

In 1939 the farm economy was still recovering from the Great Depression and the “Dirty ’30s.” I knew my future was not in agriculture. I enrolled in a correspondence course offered by TWA out of Kansas City. They had just begun passenger service. I signed up to be a code operator on the airlines.

That is when I learned a valuable lesson—how to stay on the beam.

To help airlines promote safety and save fuel, they erected transmitters on the ground and installed receivers in the passenger planes. Using carrier waves they beamed the code A(.-) on the left side of the plane and N(-.) on the right for flights between Kansas City and Chicago. If due to weather a pilot let the airplane drift too far left the code for A came on and he pulled back on beam. The same for the right side drift. If the code for N came on, the pilot pulled the plane 20 back on beam. Operating by the beam did not last long because of the advent of voice communications and new technologies.

But I never forgot the value of that example for running my life. The beam is conscience and it is operated by the Holy Spirit who sends out signals for right and wrong.

In monastic life it may be vows—staying on the beams of conversion, obedience and stability.

But as Father Louis noted, all of us are called each day to straighten up and fly right, to stay on the beam with Jesus Christ.

Ray Wyatt

Tempe, Arizona

KANSAS MONKS why do we need benedictines?

spring 2009

The bright young student, the son of nobility, fled to the hills to escape what he viewed as a city overrun with debauchery and sloth. He was certain Rome would succumb to its sins and that it would drag him down with it if he weren’t vigilant. Reclusive, living off the land, seeking shelter in a cave, this pious hermit eventually was sought out by others, who claimed they hungered for his leadership.

The bits and pieces that are known about the life Benedict of Nursia have survived the past 1,500 years with the hearthside echoes of legend, captured for posterity and for their Christian wisdom, by the quill and parchment of St.Gregory the Great in his Dialogues.

Tales tell of his followers, who came to bristle under his discipline, attempting to poison him, only to watch his goblet shatter before when he blessed it. Another attempt to off him was foiled when a Raven flew through the window snatched poisoned bread from Benedict’s hand and carried it away. There are tales of miracles. Of Benedict raising young men from the dead, of casting a demon from a large boulder so that his monks could lift it during the construction of a monastery, and watching his twin sister Scholastica’s soul ascend to heaven in the form of a dove.

However, what St. Benedict of Nursia is best known for is his Rule, a slender volume written in the mid-sixth century, which describes spiritual doctrines and a rhythm of daily life practiced in a community. He is universally known as the father of Western Monasticism.

On the following pages, through the eyes of some members of St. Benedict’s Abbey, we will explore the three vows proclaimed by Benedictine monks—Obedience, Conversatio morum, (roughly translated as “conversion of life,”), and Stability—as they embark on a lifelong journey, guided by Benedict’s Rule.

In the time between when he left Rome and when he wrote his Rule, St. Benedict gained timeless wisdom that in its simplicity, yearning and humility has had much to offer people for centuries. Although a bit dry in places, the =, especially in its prologue, bursts with promise, optimism and expectation. This document, written by a gentle but practical abbot, remains as relevant today as ever. If only—and herein lies the entire challenge, and in the 21st century, the problem—one is willing to listen with humility.

Lay Catholics and Protestants, diocesan priests and popes, corporate CEOs and recovering alcoholics and drug addicts. Diverse are the people who have found inspiration, serenity and direction in Benedictine spirituality.

This year is my tenth as an employee of Benedictine monks. In that time many monks and women religious have become treasured friends who have shown that all are worthy of unconditional love. A monk married my wife and me, baptized my children, is godfather to my youngest daughter. Monks and sisters taught me the comforting tenet that progress not perfection was to be sought in life. They have demonstrated the richness of a mature and unswerving prayer life. They have helped me understand the importance of community, not only its value to my progress as a human being, but also my own gift as a witness to it. They have unwrapped the wonder of silence. And they have revealed that obedience with humility is liberating rather than restricting.

The presence of Benedictines in our world, the monastery on the hill, people of deep faith gathering four, five or six times a day to lift the world to God in prayer, is something to behold. The secret, like with great art, is that you can’t appreciate it and learn from it unless you slow down, indeed, unless you come to a complete stop. The kind of stop that creates a moment in which you can feel your pulse slowing and hear the rhythm of your own breathing. Like a family heirloom, Benedictine monasticism is to be treasured and protected. Like an heirloom it is filled with great beauty, instilled with tradition. It is a reminder of what we value. It is passed on quietly from generation to generation, a fragile inheritance handed down with great hope that future generations will value and sustain it as ancestors have. Cultures have tried to destroy it—to be sure our current culture is inadvertently making an attempt—but a select few keep it alive and it withstands the test of time. That select few are not only those men and women who answer the call to a monastic vocation. They are simply the caretakers who are fortunate enough to hold out the monastic life and present it to the rest of us as a gift of great insight, peace and spiritual progress.

Obedience, conversion and stability. These are three gifts that Benedict handed down to his followers. Through Benedictine hospitality, they offer them to their friends outside the monastery—that is if we are willing to slow down, take a deep breath, and listen.

SUMMER 2009 Marked with the sign of Faithc f

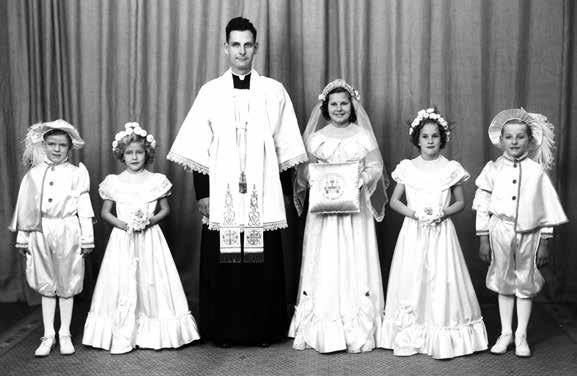

Father Wilfred Fangman (1924-1999)

C Cletus Fangman was born in Seneca, Kan., March 7, 1924. The George Fangman family lived along Highway 178, a few miles south of St. Mary’s Church, St. Benedict, Kan. The area became known as “Wildcat” after the creek there, which was so named for the abundance of those animals along its banks and surrounding timber.

The Fangman family farmed on land near their home and Cletus graduated from the St. Mary’s Grade and High Schools. These schools are now a part of the B and B (Baileyville and Benedict) school system. Cletus came to St. Benedict’s College, entered the community as Frater Wilfred, professed first vows as a member of the Abbey Aug. 15, 1944, and was ordained Dec. 17, 1949. While a cleric, he was the Abbey infirmarian and a prodigious farm worker as were his confreres: Edwin, Alphonse and Hilary.

After ordination Father Wilfred was sent to Maur Hill where he taught, served as infirmarian, and commuted across town to the Abbey to finish his theology studies.

He taught English and drama, and was moderator of the yearbook and student chaplain. As a teacher of developmental reading he helped many students. Perhaps more importantly he was the older monk many of the younger monks and new faculty respected and looked to for fresh ideas and ways to implement them. He was a man ahead of his time, as he seemed to anticipate in his own style the Vatican II vision of the Church.

In 1969 he took up parish work at St. John’s Parish, Burlington, Iowa, then moved to St. Benedict’s, Atchison, as co-pastor with Father Roderic Giller. He served at St. Benedict’s, Kansas City, Kan., from June 1984 until his death.

Father Wilfred faced back and neck problems with courage. He also spoke from his heart and held considered opinions that were not always universally popular. He was a great homilist, concrete and to the point.

It has been said that in earlier times St. Benedict’s Abbey was composed largely of two groups. One group was composed of so-called “Packing House Irish” from St. Benedict’s Parish in Kansas City, Kan. The other was “Nemaha County farmers” from Seneca, Kan., and St. Mary’s Church at St. Benedict, Kan. As I recall it was Father Malachy Sullivan who made that statement. He himself was from the group of Irish. Both groups knew what hard work was all about.

“For those of us from the city who were used to a work day that went from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.,” retired Abbot Owen Purcell recalls, “it was a cultural shock to work with people who started before dawn and had supper at 10 p.m. Father Wilfred was used to work as were other monks like Father Hilary Heim and Wilfred’s late brother and former member of the community, Herman (Tom) Fangman. Wilfred had multiple tasks as a teacher, drama instructor, infirmarian, and yearbook moderator at Maur Hill Prep School, and yet he would frequently do manual labor on a Saturday or after the school day.”

Father Wilfred was a catalyst for the faculty. His example drew many of us from the TV set to play volleyball and basketball with the students on a Friday night. During the spring after Sunday morning study hall there was a faculty-vs-student baseball game. A monk pitched for the students and a student for the monks. “Wilfred could drive a ball a mile and it took almost that long for him to reach second base!” Abbot Owen says.

But Wilfred was not all work. He was a reader and thinker. He would decry time spent watching the “tube.” “Turn it off,” he would say when he came to the common recreation room. He loved poetry and we spent some evenings reading a favorite one. Wilfred was an alive person and one quick to catch the spirit of what was happening at Vatican Council II. He had an oversize copy of what he called “A Communitarian Prayer” on the wall of his English classroom.

“Wilfred’s heroism in the face of crippling back problems for us was legendary,” Abbot Owen recalls. “He carried the same consistency throughout his life as a friend, monk, teacher, and good shepherd.”

Editor’s Note: Abbot Owen Purcell is at work compiling a necrology of St. Benedict’s Abbey, a volume of profiles on the deceased members of the Abbey. This document offers a thorough and entertaining look into the history of the Abbey, one monk at a time. If you have a comment e-mail Abbot Owen: ojposb@yahoo.com.