5 minute read

The Poetry of Providence

A Conspiratorial Benedictine and a Golden-Mouthed Preacher on the Dating of Christmas

By Dr. James R. A. Merrick

Ilivedin Scotland twice for a combined five years.

Two of my children were born there, and it is the birthplace of my Catholicism, having been received into the Church with my family in 2017. Surrounded by the remnants and ruins of ancient and medieval civilizations, I couldn’t fight the urge to become part of the grander and nobler trends of history by entering the Church Catholic.

Living in Scotland was overall an enriching experience. But there was the occasional “culture shock.” The prevalence of instant coffee in a place so proximate to continental Europe and that understood the importance of maturing spirits was confounding. More shocking, however, was the discovery that until relatively recently the observance of Christmas was discouraged in Scotland, with some of the historic traditions having been outlawed by Scottish Parliament in 1640. It wasn’t until 1958 that Christmas was restored as a public holiday. To this day, “Hogmanay,” or New Year’s Eve, overshadows Christmas.

It might surprise you, as it did me, that a Christian country would practically ban Christmas. But seventeenth-century Scotland was shaped by the Protestant Reformation, especially the Calvinist branch. And Protestants generally felt that the Catholic Church needed to be purged of various superstitions and purportedly idolatrous practices that had crept in over the centuries through contact with paganism.

Calvinists felt that if something wasn’t explicitly commanded in the Bible then it shouldn’t be enjoined upon people. As John Knox, leader of Scottish Presbyterianism, wrote, the feast of Christmas has “neither commandment nor assurance” in the Bible and therefore was to be “utterly abolished from this Realm” (History of the Reformation in Scotland, vol. 2, p. 281).

Calvinists also believed that sin inclined humans to substitute ritual adherence for sincere faith. Thus, they suspected the observance of Christmas to be full of various rituals and traditions that obscured the real significance of Christ’s birth and obstructed genuine faith.

This general skepticism toward Catholic tradition developed in the decades that followed to the point where many leading lights thought most distinctly Catholic practices could be attributed to the influence of paganism. Because paganism was typically held to be superstitious and inferior to Christianity, when Catholic traditions could be traced back to pagan roots the narrative of Catholic corruption of Christianity could be advanced, a narrative as expedient politically as theologically.

When it came to the question of the date of Christ’s birth, it became popular to attribute the choice of the date of December 25th to the pagan festival of the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun or Sol Invictus. The Benedictine monk and classicist Jean Hardouin was a noteworthy proponent of this view. But it was his Protestant contemporary Paul Jablonski who took the theory and turned it once more into evidence against the Catholic Church.

Hardouin was somewhat of a conspiratorial thinker, though his skepticism of medieval learning was at home in his day. He once claimed that the vast majority of ancient literature and artifacts were forged during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. But Hardouin did not invent the theory of the pagan precedent for the date of Christmas. It was noted in the twelfth century by an Orthodox bishop, Dionysius bar Salibi.

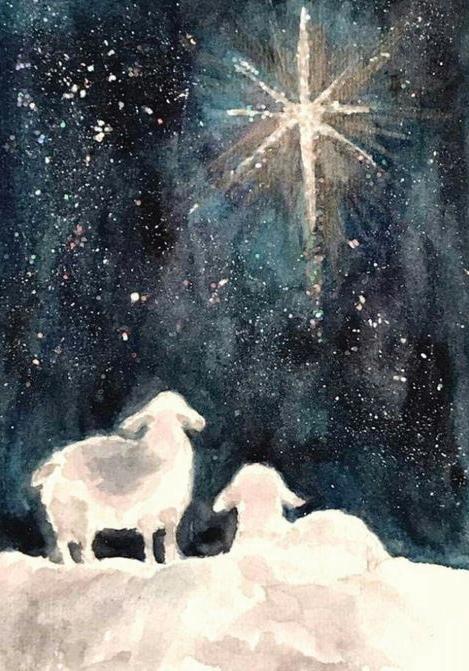

Dionysius was likely overinterpreting patristic statements about the coincidence of Christ’s nativity with the birthday of Sol Invictus. The famed fourth century preacher, St. John Chrysostom, known as the GoldenMouth, said the fact that Jesus, the true light of the world, was born on the same day as the Roman sun god was clearly Providential.

The late Pope Benedict XVI remarked that this old theory of Christmas as a replacement for Roman pagan festivals “can no longer be sustained” (Spirit of the Liturgy, p. 108). Part of the reason is that Sol Invictus doesn’t appear to have been all that popular in the Roman Empire until the late third century reign of Emperor Aurelius, who promoted the cult as part of his plan to inaugurate the rebirth of Rome. But the festivals of his reign primarily occurred during the month of August. The earliest evidence that identifies December 25th with the birth of Sol Invictus comes almost a century later from a calendar dated to the year 354, which, significantly, also identifies Christmas on that date.

The other issue is that Christians recognized December 25th well before Sol Invictus was made popular and at a time when, as Andrew McGowan of Yale points out, they were more zealous to distinguish their religion from paganism than to use paganism as an evangelistic tool.

At the dawn of the third century, decades before Aurelius assumed the throne, there were at least two figures claiming Christ was born on December 25th, St. Hippolytus of Rome and the Christian historian Sextus Julius Africanus. Consequently, the liturgical scholar Thomas Talley has gone so far as to say it was the Romans who co-opted Christmas for Sol Invictus not the other way around.

Scholars such as Talley have argued for what is now being called the “calculation theory” of Christmas. This theory doesn’t read Christian dating as a mere repurposing of prior pagan festivals. It points out that the early Christians were very concerned both with biblical chronology and the symbolism of time. Africanus, for example, argued for December 25th because it was nine months later than March 25th, which was the traditional date for the Annunciation and, he added somewhat bizarrely, the day God created the world.

In a late fourth century homily on the date of Christmas, the aforementioned preacher, St. John Chrysostom, looked to the Gospel of Luke for his own calculation. Luke has the most chronological information about Jesus’ birth. St. Luke tells us that Mary conceived Jesus six months after Elizabeth became pregnant with John the Baptist (Luke 1:26). It further tells us that Elizabeth conceived shortly after Zechariah returned from completing his priestly service in the Temple (Luke 1:23-24).

According to Chrysostom, since Zechariah was a member of the priestly division of Abijah (Luke 1:5), he would have been serving in the Temple during the month of September and would have returned home late in the month. Traditionally, the Conception of John the Baptist was celebrated on September 23rd. If Elizabeth conceived John in late September and Mary conceived Jesus six months later, this puts the conception of Jesus right around the traditional date of March 25th for the Annunciation. Nine months later is December 25th.

For St. John Chrysostom, the coincidence of Christmas with winter solstice and Roman solar festivals was an instance of the poetry of Providence. He did not see these coincidences as cause for suspicion but as confirmations of faith and the working of divine wisdom. While many today, including perhaps many Catholics, view the date of Christmas, if not Christmas itself, like they view the legends of Santa Claus, hopefully we can now see that the early Christians were not merely shrewd culture warriors, but people of faith who did their best to understand what had been revealed to them. And perhaps this Christmas we can move past all the skepticism and incredulity that surrounds us and regain something of Chrysostom’s faith that looks at history not as a series of random reactions but as the poetry of Providence.