2 minute read

How even Jenner was trolled 200 years ago

Generations before computers, the internet, and social media made human interaction so easy, even medical pioneers like Edward Jenner, the Father of Vaccination, had to cope with strident criticism.

Sometimes the concerns voiced were legitimate and understandable, faced with the new smallpox vaccine. But sometimes scepticism and questioning turned into hysteria and exaggeration, fuelled by eye-catching cartoons like the grotesque one from 1802 on this page.

Advertisement

Dr Jenner was the target of 19th century anti-vaxxers, but he had no shortage of admirers.

Should ‘Welsh Elgin Marbles’ be returned?

The 30,000 year old human remains found in a cave in the Gower Peninsula in January 1822 were those of a man, as initially thought, although the body was inaccurately renamed ‘the Red Lady of Paviland’ soon after. They are on display in Oxford’s Museum of Natural History о Interview by ABC Radio, Australia о Heritage trail in Berkeley launched by Jenner Project о Jenner plaque unveiled in Cirencester о Wikipedia, including further reading

A newspaper epitaph called him “the great physician of the human race” and hailed “Immortal Jenner, whose gigantic mind brought life and health to more than half mankind”.

Dr Jenner’s House at Berkeley, Gloucestershire, is now a museum and re-opens in April. It includes the Temple of Vaccinia, a small summer house that became the world’s first vaccination clinic.

Discovered by an Oxford University academic, it was inevitable they would cross the border for examination.

Notes From Now

Observations about the news from 1823

The death of the hugely wealthy John Julius Angerstein in January 1823 triggered events that led to the opening of the National Gallery in London in 1824.

Angerstein’s 38 paintings were bought for the nation in the same year for о £57,000 and formed the cornerstone of a new national collection. The pictures were displayed at Angerstein’s house at 100 Pall Mall until the gallery in Trafalgar Square was built.

Both the National Gallery and Lloyd’s of London, where Angerstein made his fortune, have investigated his economic connections with slavery and the slave trade. His early wealth came from marine insurance, with its inevitable links to the transatlantic trade in people and goods. But research has found no evidence that he was a slavetrader or slave-owner, or that financially he benefitted directly himself.

But there are calls for them to go back to Wales, even likening this to the campaign for the Elgin Marbles to return to Greece. Some 1823 finds were sent back: fox teeth are at Swansea Museum, and a bone spatula at St Fagans National Museum of History, Cardiff. But the UK’s oldest human remains remain in England.

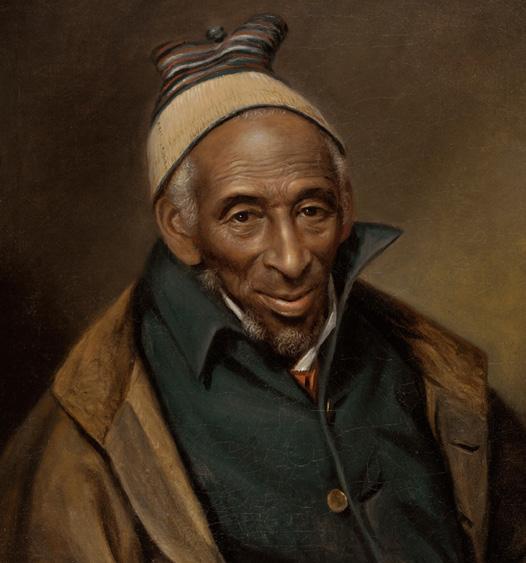

In Washington, January 1823 saw the death of Yarrow Mamout. Born in West Africa around 1736, he was enslaved and taken to America in 1752. He was the property of a plantation owner for 44 years until freed in 1796 because he was believed to be too old to work. Mamout bought his son’s freedom, saved and invested, and became a property owner and entrepreneur, an extraordinary end for an ex-Muslim slave. Portraits of Mamout are held in galleries in Washington and Philadelphia and his family’s biography was written by historian James H. Johnston

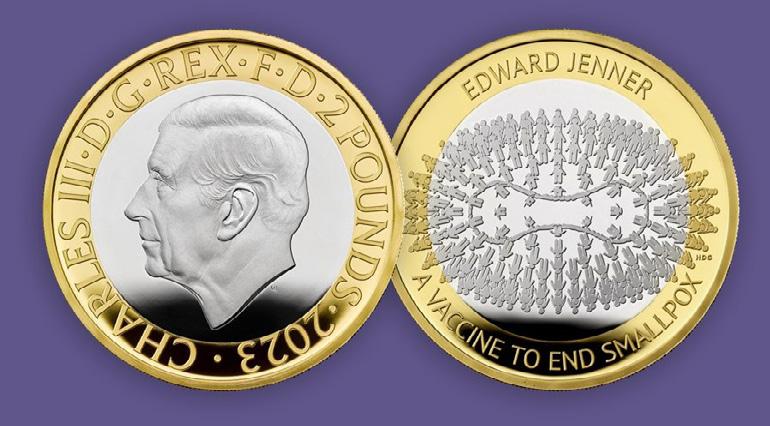

The Royal Mint Experience at Llantrisant, South Wales, lets members of the public strike a £2 coin like this themselves. They can also be purchased online from £12.

Stephenson events begin

The bicentenary of the locomotive company founded in June 1823 by Stockton & Darlington Railway pioneers Robert Stephenson and his father George is being marked by activities in Newcastle this year. These include an exhibition at the city’s Common Room until late March, and a variety of talks at the same venue

200 is edited by John Evans. Thanks to Jane Evans, Jude Painter, Larry Breen, British Newspaper Archive, Cambridge University Library, Central Bedfordshire Libraries. Email: feedback@200livinghistory. info Copyright issues/takedown requests: john@freehistoryproject.uk