8 minute read

Musicwoman Magazine Spring 2020

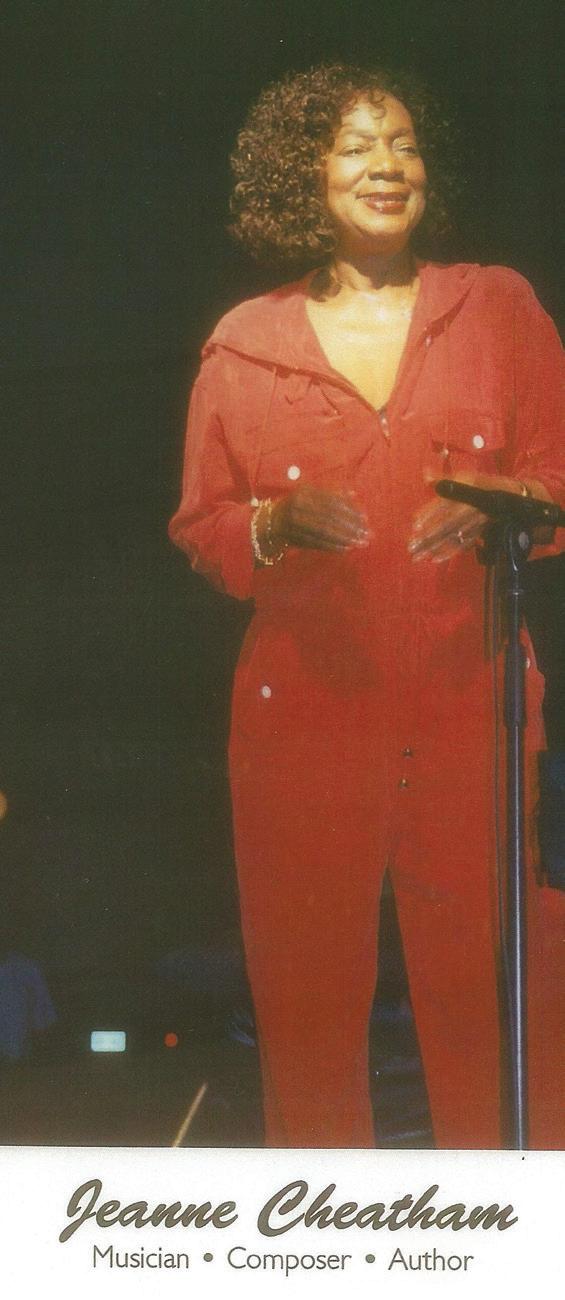

Jeannie Cheatham

All photos of Jeannie Cheathan are by Meredith French

Advertisement

JEANNIE CHEATHAM

By Mariea Antoinette

(MC): My first question is, how did you come to music as a child and did you study music theory?

Jeannie Cheatham (JC): Yeah to both. I did some music like most black kids, through church. I started playing for church when I was about five years old because the one-armed piano player we had went to Detroit.

MA: One arm?

JC: He did. He had one arm cutoff, but he would play enough for the church to do the hymns and sing. But we didn’t think it was anything because he got over the keys. So, I took over when I was five years old. But I didn’t take over, formally, until I went to school at six years old. I took lessons from a piano teacher that came around once a week on Saturday. Mr. HH, who came from London, England, Arthur Riley.

MA: Was he a white guy or black?

JC: He was white. I got a thorough browning in classical music with him because I took lessons with him until I was thirteen years old. I used to play classical music and church music.

MA: Nice mix! You had the gospel and the structure. That was a good balance.

JC: Exactly. It made for a good background. He was very strict. He used to make me practice scales with pennies on the back of my hand.

MA: Oh wow, for a good hand position?

JC: You betcha!

MA: Well, I had a Russian teacher, so I know that whole drill.

JC: You know what I’m talking about, then.

MA: Yes, I know exactly what you’re talking about!

JC: The whole routine, they’re very thorough.

MA: You have to play it right.

JC: Yeah. A couple times I wanted to go out and play ball. But I was taking my lesson and he said

Mariea Antoinette

“Mrs. Evans, Jeannie is not ready to study, today” and he’d get up and walk out.

MA: What?

JC: Yeah.

MA: Well, you know that’s that the foundation, ya know, the strictness because they want it right.

JC: Yes. I wouldn’t give anything for the grounding and foundation, the fingering. All the musicians said, “You got perfect fingering.”

MA: Technique!

JC: It also teaches you not to have problems with your hands. I’ve never had problems with my hands, carpal tunnel or any of that stuff. No. They gave exercises to make sure I didn’t get arthritis.

MA: That’s interesting because I’m a harpist. A lot of the harpists that have been in the game for a minute have problems with their hands. But I had a Russian teacher. I don’t have issues with my hands at all and she said, “If you do the technique right, you can play forever.”

JC: Forever. That’s right!

MA: Do you compose music?

JC: Yes. All the albums we recorded is my music. Jimmy [Cheatham] did the music and I did the writing. We have 10 or 12 albums with our label Concord Records. People are still buying them and what amazes me is they always say that a band or orchestra lasts about seven years. Unless they change the track you gotta keep reinventing yourself. But they’ve been playing with Speed Records, since we recorded in 1980’s and they’re still playing it, all over the world.

MA: And probably a lot more. I would think maybe in Europe.

JC: All over the world.

MA: Yeah, because they have an appreciation for your music.

Con’t on page 53

Interview with JEANNIE CHEATHAM by

JC: The reason I know is because ASCAP keeps track. I belong to ASCAP and they send me royalties every six month or so. They send me a check and on the back of it is listed everywhere it has been played on the radio, TV, or by personal appearances. All the countries you can think of are listed, some I don’t even know.

MA: That’s quite a bit of history.

JC: Oh Yes!

MA: Is there anything in your career that stands out as a stellar point or moment that you’ll never forget?

JC: I think the whole thing. The thing is that most jazz musician are operating on a different frequency. They proved that, scientifically, where the brain fires up and where it doesn’t fire up. Jazz musicians have a thing about the brain, a blood brain barrier that is unique because of the improvisation. You can’t just sit there and play something you’ve been practicing like Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, or any of the classical music. You practice and practice -=and practice until you get it right.

MA: Right.

JC: But with jazz you don’t know what you’re gonna do when you get up there. You gotta have a certain kind of faith.

MA: Yes, you have to trust yourself.

JC: That’s it, trust where the music is gonna come from. That’s exactly what I’m talking about, because you got musicians I know, real selfish musicians. Very good as far as manipulation, I mean manipulation of the instrument, but they don’t have any soul.

MA: I see.

JC: But all the guys in my band had soul and faith. There were all different kinds of religions in the band. Some of them switched to Buddhism or they were Muslim. But they were aware of where that music came from and they were loyal. I still have contact with my trumpet player, Nolan Shaheed, and Charlie Owens. One of them died. I’ll be 92 tomorrow [August 14, 2019].

MA: Wow! Congratulations.

JC: But they were younger than me and they are still loyal. Yea, ya know, when I said, they would

Mariea Antoinette (con’t)

drop their things to do what we were booked for, all these years, from 1983, until today, over 40 years! That was the advantage and none of them were dope addicts. We all drank gin and Courvoisier for me. You could sip one or two, which could last all night and for a vocalist it warms your throat. You never use ice.

MA: Because if it’s cold, it’s something else.

JC: It messes with your vocal cords.

MA: How many songs have you composed?

JC: Oh, I don’t know. Sometimes, I keep some of this close because, sometime people call from all over. This morning I got a call from Israel at four o’clock in the morning.

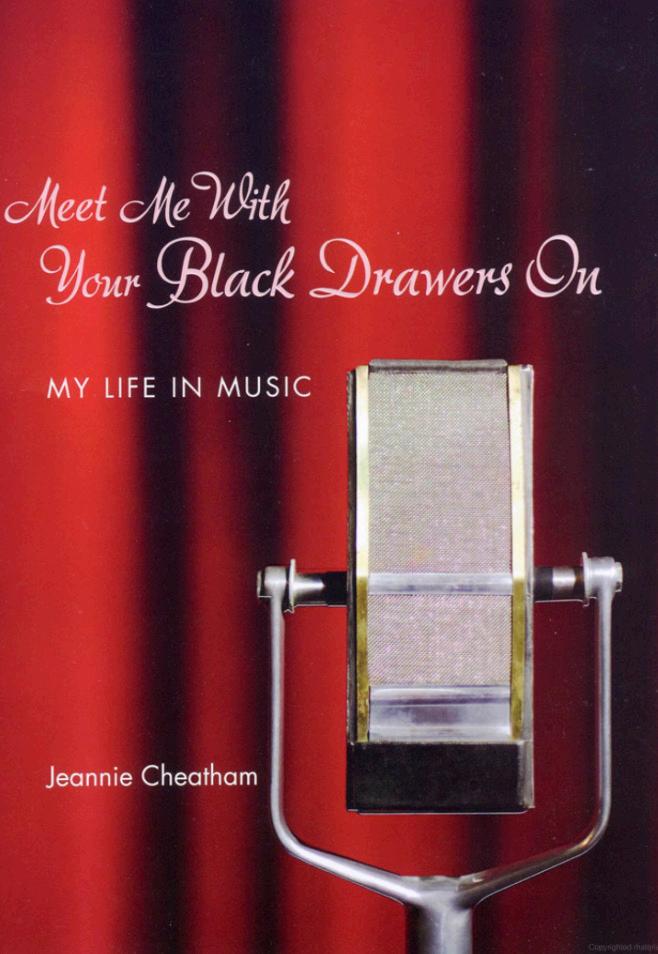

Jeannie Cheatham is a living legend in jazz and blues. A pianist, singer, songwriter, and co-leader of the Sweet Baby Blues Band, she has played and sung with many of the greats in blues and jazz—T-Bone Walker, Dinah Washington, Cab Callaway, Joe Williams, Al Hibbler, Odetta, and Jimmy Witherspoon. Cheatham toured with Big Mama Thornton off and on for ten years and was featured with Thornton and Sippie Wallace in the award-winning PBS documentary Three Generations of the Blues. Her music, which has garnered national and international acclaim, has been described as unrestrained, exuberant, soulful, rollicking, wicked, virtuous, wild, and truthful. Cheatham's signature song, "Meet Me with Your Black Drawers On" is a staple in jazz and blues clubs across America and in Europe, Africa, and Japan.

In this delightfully frank autobiography, Jeannie Cheatham recalls a life that has been as exuberant, virtuous, wild, and truthful as her music. She begins in Akron, Ohio, where she grew up in a vibrant multiethnic neighborhood surrounded by a family of strong women. From those roots, she launched a musical career that took her from the Midwest to California, doing time along the way from a jail cell in Dayton, Ohio, where she was innocently caught in a police raid, to the University of Wisconsin-Madison—where she and Jimmy Cheatham taught music. Cheatham writes of a life spent fighting racism and sexism, of rage and resolve, misery and miracles, betrayals and triumphs, of faith almost lost in dark places, but mysteriously regained in a flash of light. Cheatham's autobiography is also the story of her fiftyyears-and-counting love affair and musical collaboration with her husband and band partner, Jimmy Cheatham.

http://jeanniecheatham.com